Style Points is a weekly column about how fashion intersects with the wider world.

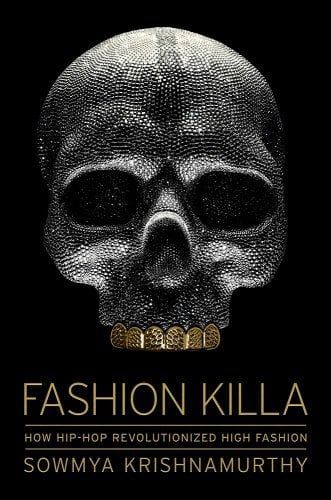

When the 50th anniversary of hip-hop came around this summer, Sowmya Krishnamurthy, like so many fans, made the pilgrimage to Yankee Stadium to watch artists like Slick Rick and Big Daddy Kane being honored. “I love seeing the legends getting their flowers,” she says. Still, for the longtime music journalist and author of the new book Fashion Killa: How Hip-Hop Revolutionized High Fashion, there was a disconnect.

The anniversary celebrations, and the media blitz that accompanied them, “focused a lot on the old school, and we didn’t really see a huge emphasis on aesthetics and style, especially as it relates to luxury fashion.” Yes, classic images of Run-DMC in their Adidas tracksuits were everywhere, but with Fashion Killa, Krishnamurthy hopes to expand our understanding of hip-hop’s impact on and interplay with fashion beyond those much-circulated moments.

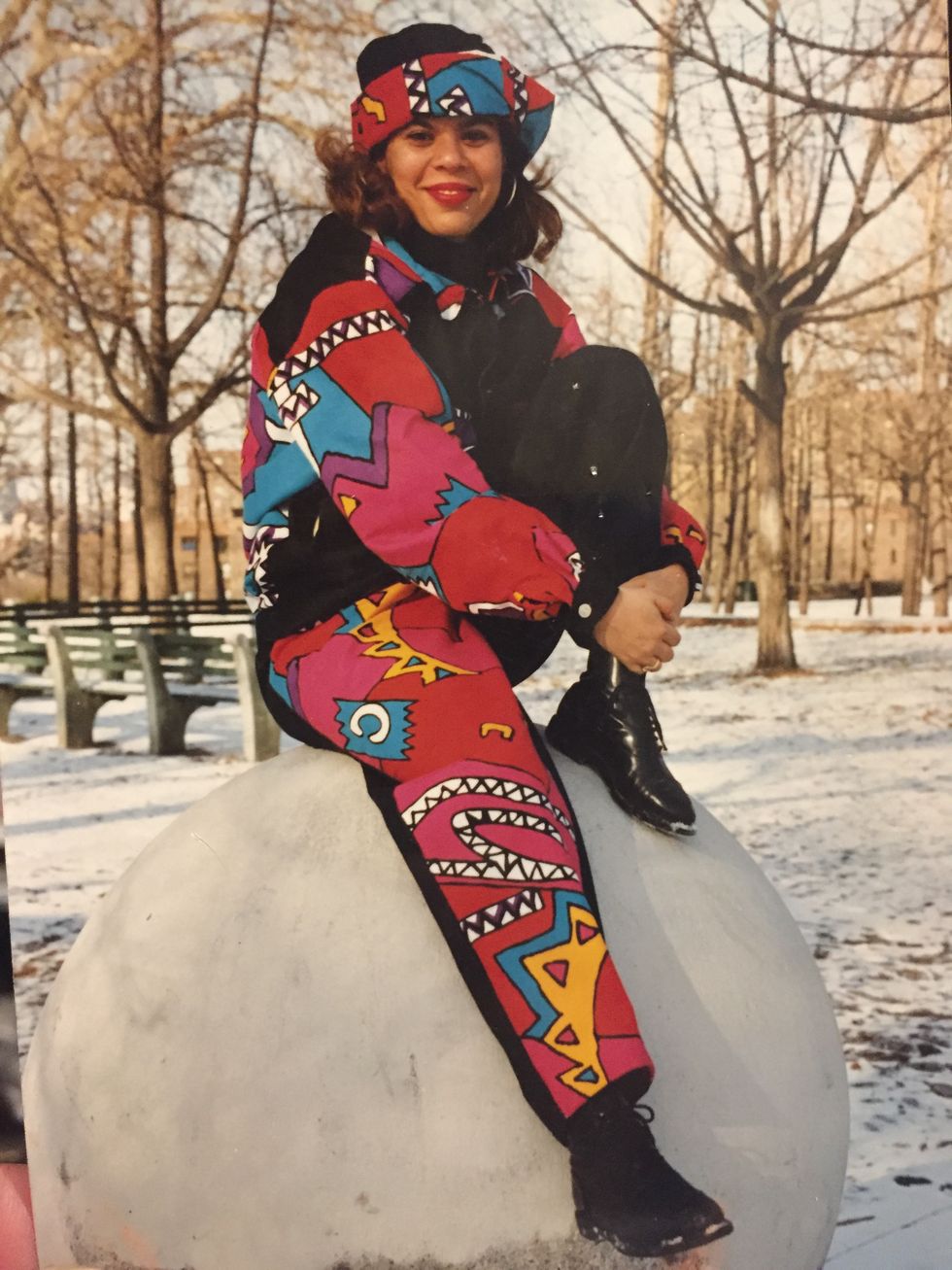

Growing up in Kalamazoo, Michigan in the ’90s, Krishnamurthy felt a bit removed from the hip-hop scene then flourishing on the coasts. But after school, glued to MTV and BET, she’d follow the scene, and the fashion, watching Lil’ Kim’s “Crush on You” video on repeat. “The wigs and the fur, the makeup, just everything being so playful and fun and ostentatious!” she enthuses. “Imagine seeing those images over and over again for months on end. We were almost self-brainwashing and fully inundated with the style.”

For the book, Krishnamurthy spoke to a number of rappers and designers, including Nas, A$AP Ferg, Meek Mill, Dapper Dan, and Tommy Hilfiger. COVID pushed some of those interviews to Zoom, but she fondly remembers her in-person encounters, like chatting with Cam’ron while he was jewelry shopping right before his Verzuz performance. Or Pusha T telling her that “he actually gives away a lot of his clothes because his wardrobe is just too big. I’m like, ‘Tell me where that Goodwill is, and I will take those clothes off your hands if you need me to.’”

Through these firsthand accounts, Fashion Killa traces the way hip-hop style evolved over half a century: from rappers emulating luxury brands, with LL Cool J and Big Daddy Kane sporting Dapper Dan “knock-ups,” to serving as inspiration for said brands, to becoming, in many cases, designers themselves and defining luxury on their own terms.

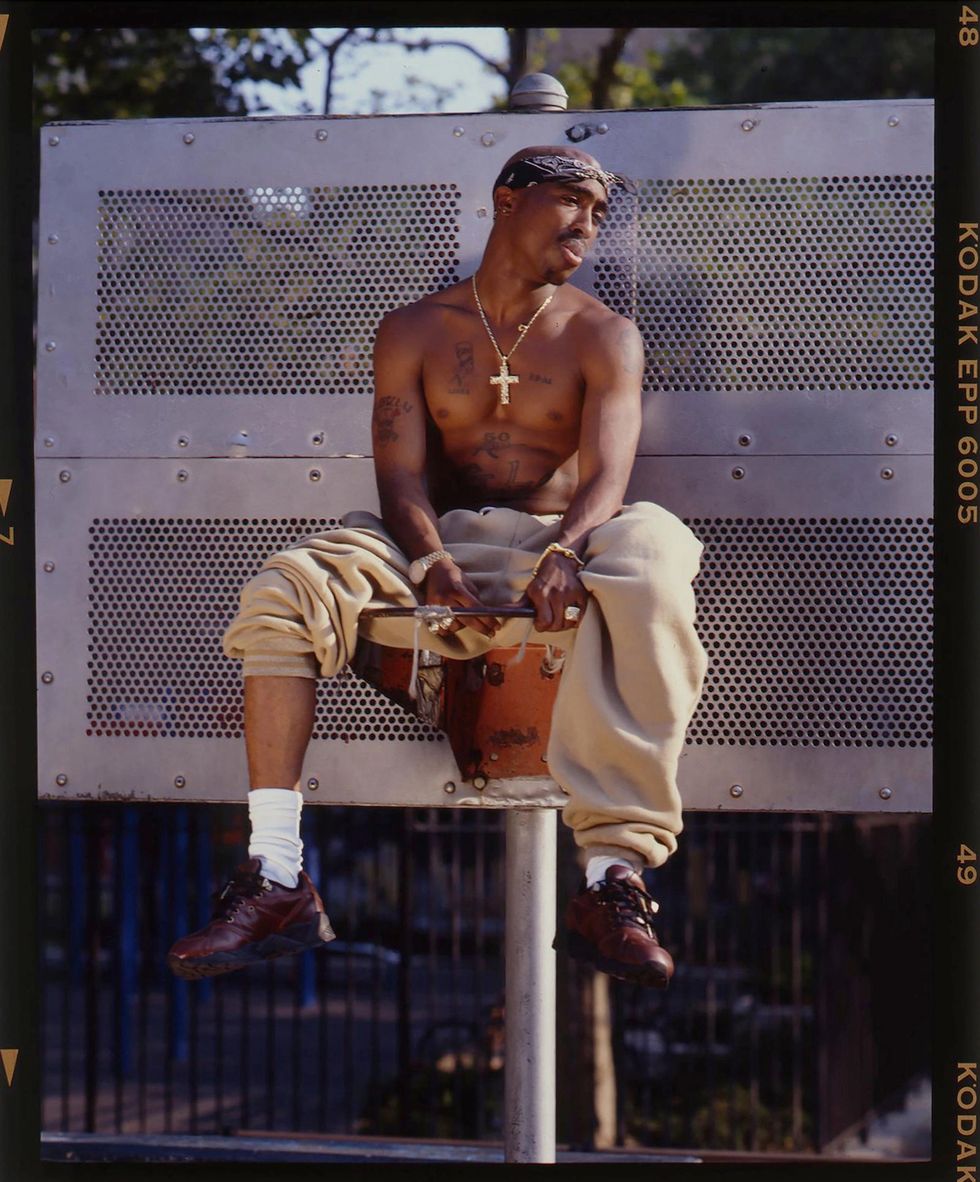

Along the way, she tells the stories of designers like Karl Kani and April Walker, who catered to rappers in the ’80s and ’90s. “Back then, they were largely minimized as so-called ‘urban designers,’ which was a way of saying that your main demographic is not white people, essentially,” she says, “but they really were successful streetwear brands. Because whether it be April having relationships with Biggie Smalls and Tupac, or Karl using Tupac and Puffy as some of his earliest brand ambassadors, they were able to work with these future fashion icons.” Plenty of brands today “are essentially riffing” on what they did, with pieces like signature hoodies or denim suits. “It’s cool that after all these decades, later those brands are being properly recognized and acknowledged,” she says, “because without them, we don’t get Sean John, we don’t get Rocawear, we don’t get Baby Phat, we don’t get any of those.”

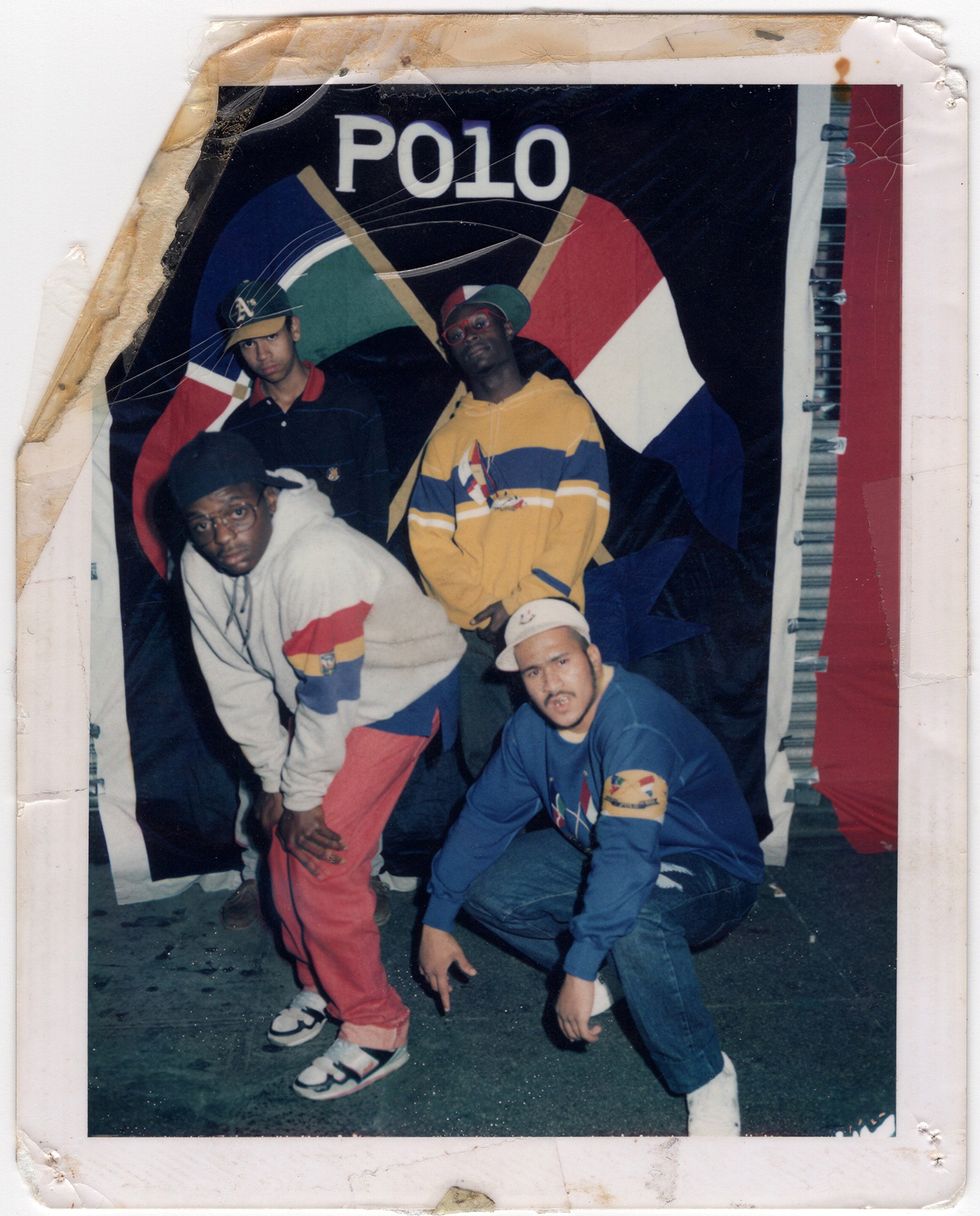

She traces hip-hop’s love affair with Polo Ralph Lauren through the story of the Lo Lifes, a group of young men in Brooklyn who started out “boosting” the brand from stores and became some of its most ardent fans. (“They were literally walking billboards, and probably connected to more people than traditional advertising.”) And she looks at the way music figures like Snoop Dogg and Aaliyah helped popularize Tommy Hilfiger. The rap fandom for both brands was intense. “It became almost a competition: ‘Are are you a Polo person? Are you a Tommy person? Are you both?’ For Aaliyah’s Hilfiger photo shoot, pieces from the designer’s men’s collection were cut up and repurposed, with a pair of men’s underwear transforming into a bandeau. “Being more collaborative and letting an artist put their own spin on it was really smart,” she says.

Soon, of course, rappers were fronting their own fashion lines. “You started seeing guys who had that entrepreneurial mindset, somebody like a Puffy or a Dame Dash. They came in saying, ‘Why are we supporting other people’s lines when our name is hot in the streets? We’re the ones moving things.’”

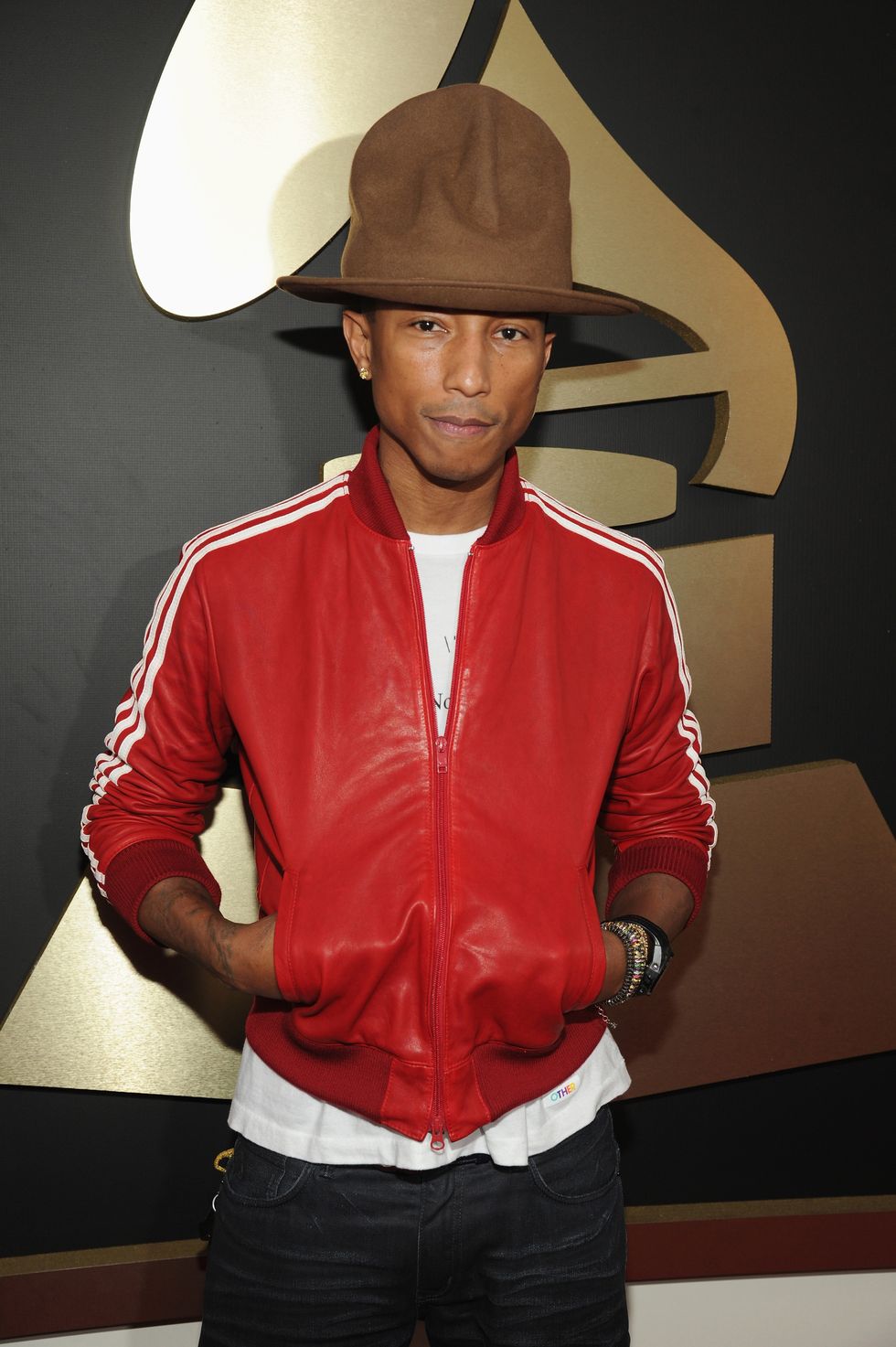

When we speak, a few months have passed since Pharrell Williams’ debut show as the men’s creative director of Louis Vuitton, a bona fide pop-culture event that drew Beyoncé, Jay-Z, and Megan Thee Stallion to the front row. Krishnamurthy calls it “a full-circle moment, in that now he’s sitting inside these rarefied rooms, where before Dapper Dan had to take logos and create his version of what looked good for the hip-hop audience. Pharrell is being welcomed with open arms and his ideas are being executed…I like to say Pharrell gave me the best period to this book.”

Another major through line of the narrative is the cohort of female rappers who helped push fashion forward. Early on, many female artists wore baggy clothes and emulated their male contemporaries’ style. When Lil’ Kim brought a more sexed-up look to the masses, “there were people, from parents’ groups to daytime TV hosts, even female fans, who were like, ‘We don’t like what you’re doing, what you’re selling. We feel it degrades you; it degrades us.’ She faced a lot of backlash.”

Those conversations carry over into the present day, with the ongoing commentary about what artists like Cardi B or Megan Thee Stallion wear. “There will always be that constant struggle, as a female artist. How much should the emphasis be on what you’re wearing, or what you’re not wearing? How much skin should you be showing? Does that somehow undermine you as an intelligent and competent and lyrically-skilled rapper?” Krishnamurthy says. “I would love to live in a world where just because you wear a bikini does not mean that you can’t be an intelligent and respected professional.”

She points out that “anytime people talk about the greatest rappers of all time, it’s rare that a woman even makes the list. And if [one does], it’s usually Lauryn Hill because she is beautiful and talented, but she was also covered-up and that makes people feel safe and feel like she’s a ‘good girl.’ It’s unfortunate, because men have been hyper-sexual and hyper-masculine since the dawn of time. No one’s going to question your morality behind the scenes: ‘Are you a good dad? Are you a good role model?’”

The most successful female rappers today, she adds, are the ones who shake off the criticism and “stay true to themselves. And if that means you ruffle a few feathers? So be it.”

ELLE Fashion Features Director

Véronique Hyland is ELLE’s Fashion Features Director and the author of the book Dress Code, which was selected as one of The New Yorker’s Best Books of the Year. Her writing has previously appeared in The New York Times Magazine, The New Yorker, W, New York magazine, Harper’s Bazaar, and Condé Nast Traveler.

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.