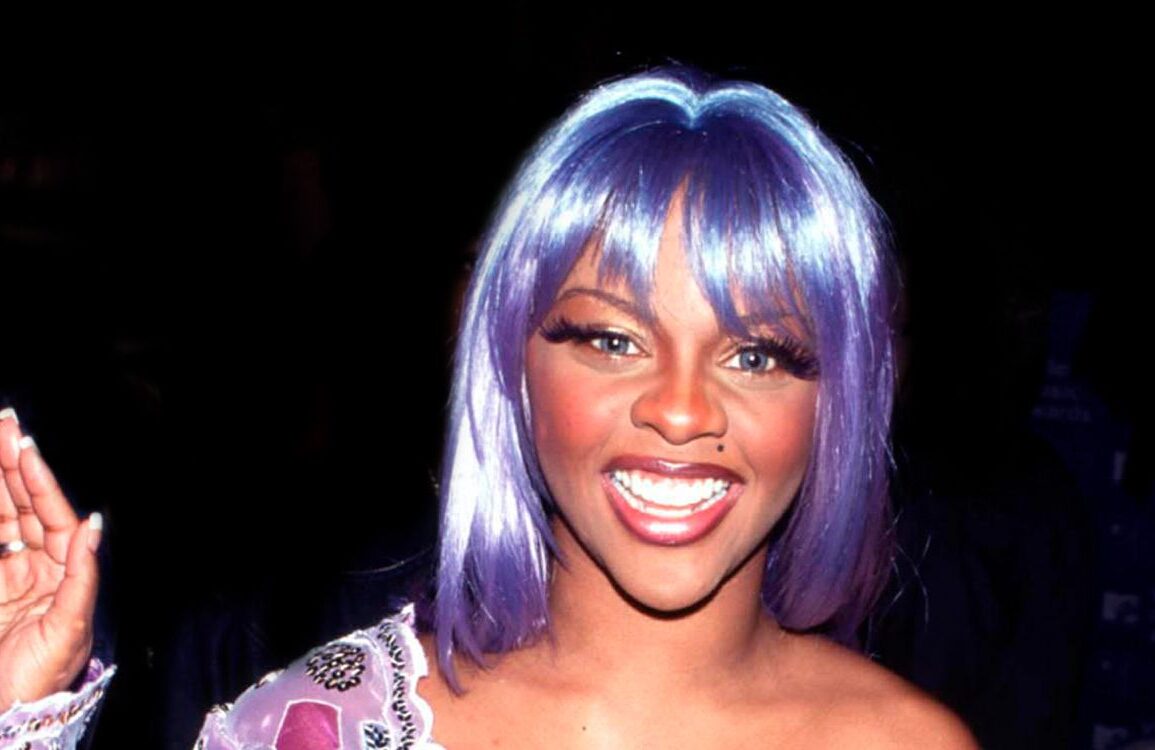

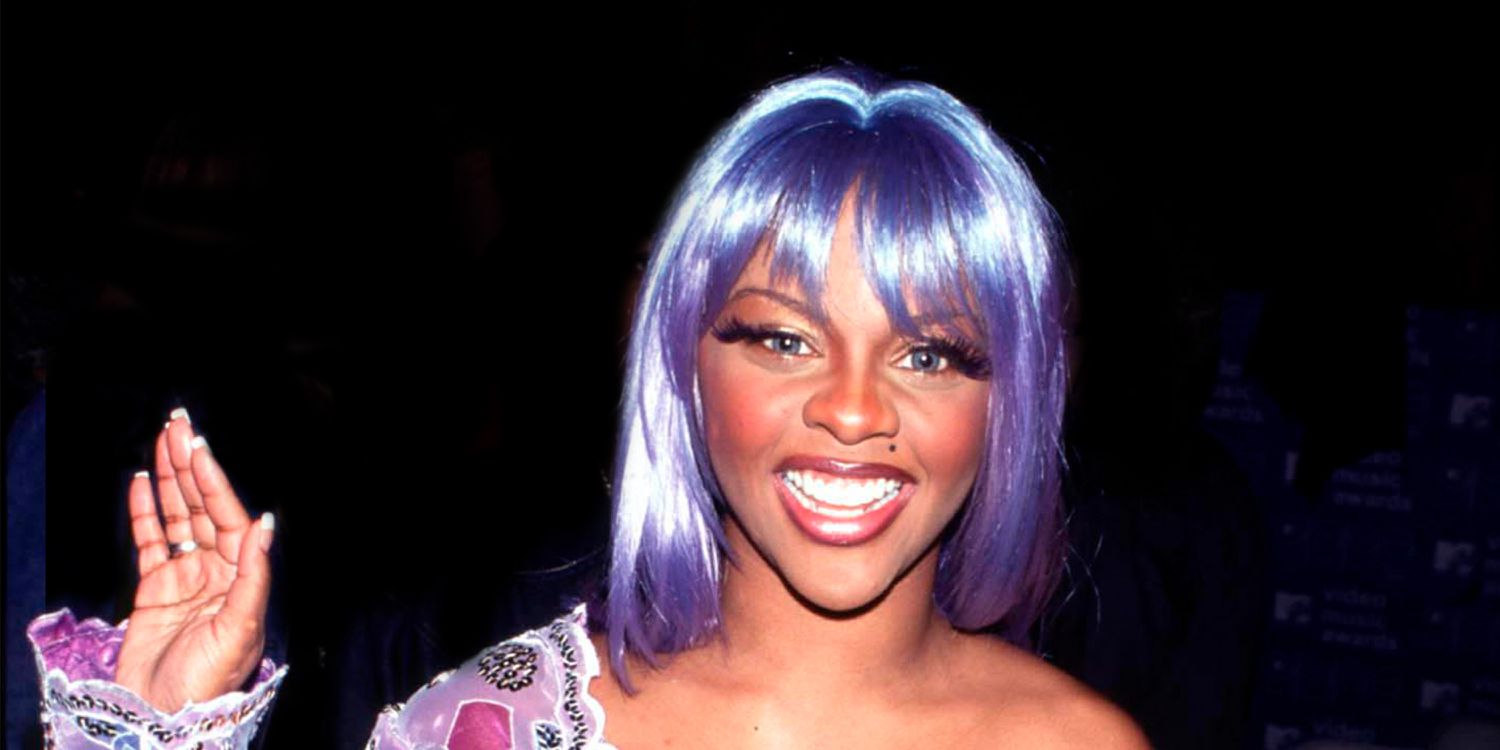

Fresh off touring with Janet Jackson and glamming Mary J. Blige for the cover of Source Magazine, celebrity makeup artist Nzingha was watching the Source Awards in her Bronx apartment in New York City. It was 1995 — the year Suge Knight dissed Diddy onstage, and OutKast was booed after winning Best New Artist. It was also the year Lil’ Kim first hit the stage with her group Junior M.A.F.I.A. to perform “Player’s Anthem,” the first single off their debut album Conspiracy. The rapper didn’t yet look like the star we know today: vibrant wigs, overlined lips, and show-stopping ‘fits. Her hair was dark, her makeup simple, and her little black dress unremarkable. But Nzingha recognized the powerhouse inside her (relatively!) nondescript exterior. “Look at how she rhymes; it’s a thunderstorm when she comes on,” says Nzingha now, describing her reaction to Lil’ Kim during that performance. “I saw her as Storm from X-Men.”

That evening, Nzingha picked up the phone and set a meeting with Lil’ Kim for the next day. From that day on, the artist would play a pivotal role in empowering the artist to embrace her femininity and molding her into the bombshell icon she is today. “There was a time when Kimberly’s albums were not selling, and the only reason why they sold was because we gave her a look, and the look is what brought her into the mainstream,” says Nzingha, who was also a beauty editor at Vibe Magazine at the time. “It was the look that crossed her over.”

Courtesy of Nzingha

Lil’ Kim’s more intentional look celebrated the star’s individuality and allowed her to shine within hip-hop’s tough, very much male-dominated scene. As Nzingha emphasizes, in the mid-’90s, because the genre was hostile towards women, female rappers like Queen Latifah and MC Lyte embraced aesthetics that blended in. Kim broke the mold and made space for other rappers, like Missy Elliot, Lauryn Hill, and Foxy Brown (some of Nzingha’s other clients), to create their own unique, career-catapulting visual identities.

“You have to understand how the era was — most of the girls at the time were wearing big overalls and Timberlands,” says Nzingha. “Queen Latifah had to address it in one of her songs ‘U.N.I.T.Y.,’ asking, ‘Who you callin’ a bitch?’ There was so much aggression towards women that the women became aggressive. They felt like they had to meet that fire with fire. But Kim and the other girls came in and brought water.”

What Set Hip-Hop Beauty Apart

Shaped by creative visionaries like makeup artists Nzingha, Eric Ferrell, and Kevyn Aucoin; and hairstylists Dionne Alexander, Tre’ Major, and Chuck Amos, female hip-hop artists started to become beauty icons — their looks just as influential and memorable as their music.

Think: Mary J. Blige’s dark lips in the “Not Gon’ Cry” video (1995); Lauryn Hill sporting her first lace-front wig in 1998’s “Doo Wop (That Thing)” video (“I had to put [her] locks underneath a wig and make it look like it was her hair, so for me, that was a defining moment in culture,” says Alexander); Lil’ Kim’s lilac wig at the 1999 VMA’s; Janet Jackson’s purple, jewel-adorned press-ons from the 1999 “What’s It Gonna Be?!” video; and Aaliyah igniting an ombré hair trend at the 2000 MTV Movie Awards. These looks are seared into hip-hop’s collective memory, defining an era of artistry and visual self-expression.

Getty Images

With this momentum, major cosmetic brands began to tap into the success of hip-hop in the early aughts. In 2000, MAC Cosmetics partnered with Blige and Kim for a Viva Glam campaign to support the MAC AIDS Fund. Their star power raised $4 million for the cause. “From that success, Estée Lauder, L’Oréal, [and] everyone else started to take note and say, ‘Okay, hip-hop is a driving force to capitalism,'” says Camille Lawrence, founder and principal archivist of Black Beauty Archives. “Let’s capitalize on that and finally give Black folks advertisements and different types of beauty ambassadorships they didn’t have access to prior to 2000.”

Queen Latifah became the face of CoverGirl in 2001. Missy Elliot (the first female hip-hop artist to be inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame) joined Viva Glam in 2004, followed by Eve in 2006. Diddy partnered with Proactiv in 2005 and launched a fragrance with Estée Lauder in 2006. In 2007, Beyoncé became the face of Imperial Armani, and Usher and Mariah Carey launched their fragrance lines. Hip-hop became synonymous with luxury.

Courtesy of Black Beauty Archives

“In the early nineties, hip-hop still had an edge to it still. But then the early 2000s is when it became ghetto fab,” says celebrity hairstylist Tym Wallace. “Companies started to see the value in what we brought to fashion. So budgets became bigger, and you could tell — everybody looked rich.”

The Lasting Impact of Hip-Hop Beauty

The visual legacy of hip-hop is especially meaningful when considering that, during the first half of the 20th century, Black people weren’t even pictured on their own album covers. “From the twenties to the fifties, music by Black people was categorized as ‘Race Music,'” says Nzingha. “The record labels would put the album out but not put the artists on the cover because they wanted to sell them as mainstream. There was a time for Black women when there was no makeup [either]. Foundation? You better have had good skin. The only thing that Black women could buy was lipstick and eyeliner.”

Courtesy of Nzingha

Since female hip-hop artists began being truly seen for their artistry, expression, and individualism through beauty in the ’90s, it’s become practically a prerequisite for stardom in the genre. “Beauty is that visual indicator and communicator when nothing else is speaking,” says Lawrence. “There’s a direct correlation between Black communities seeing the freedom, liberation, and improvisation of hip-hop and identity formation and our community showing up in droves to support.”

The confluence of beauty and hip-hop created another avenue for fans to engage and feel connected to the genre. “When it comes to that intimate connection between you and the artists, these beauty things are at a more accessible price point than a concert ticket, so everyone can engage with it,” says Lawrence.

Courtesy of Black Beauty Archives

The trends established during the hip-hop beauty boom extended into culture at large. Take neon-bright hair, for example. The look reached new heights after Lil’ Kim put it on the map. “We were stuck in brunettes, reds, and blondes,” says Alexander, who was behind the star’s iconic hair looks. “If I told somebody in the ’90s that we’d all be wearing colored hair, they’d be like, ‘Nah, you’re crazy.’ And now look. Color has totally changed hairdressing and how people feel and view themselves.” For makeup, the techniques queer makeup artists like Aucoin and Ferrell brought into hip hop from drag and ballroom culture — sharp winged liners, snatched contour, and dramatic high-arch brows — have become mainstays in modern application.

And like many trends from the ’90s and ’00s, these looks are all back in style. “The girls are wearing the half-up half-downs,” says Wallace, hairstylist to Blige and Taraji P. Henson. “You see a lot of braided styles, hair accessories, bamboo earrings, long nails, [and] heavy, not-so-blended lip liner. The pinups, the molded swoops with jumbo curl ponytails, the flips, the twists with the hair barrettes and spikes — it’s all what’s being done now.”

Although stars are dipping back into older hip-hop beauty trends, much room remains for further innovation and inspiration. “I love hip-hop so much because it’s our art form, and we’re able to redefine and reinvent it,” says Lawrence. “It’s a safe space to play and experiment with how we want to show ourselves. Hip-hop is never going to go away. It will only keep getting bigger — it’s 50 years young.”

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.