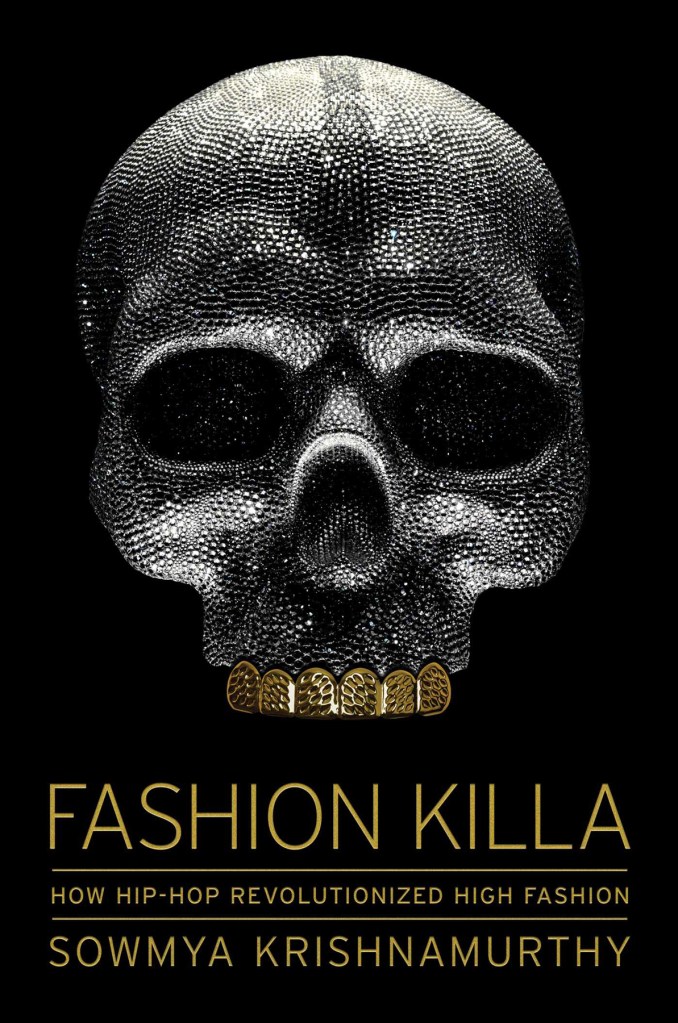

Luxury fashion has become synonymous with hip-hop, though not too long ago, many of its institutions would have turned their noses up at the rap stars who dominate pop culture today (and racism is still resonant in the industry despite modern strides). In her book, Fashion Killa: How Hip-Hop Revolutionized High Fashion, longtime music journalist Sowmya Krishnamurthy chronicles the unique and often unlikely kinships — forged through family, friendships, and sometimes simply fame — that have been the basis of legendary collaborations between labels and tastemakers in Black music. In this exclusive excerpt, Krishnamurthy looks at how women in rap and design changed the game in the 1990s and early aughts, particularly Lil’ Kim, Donatella Versace, Kimora Lee Simmons, and the circle of superstars around them.

Lil’ Kim’s Hard Core album — two million copies sold worldwide — was a fun, raunchy romp distilled into one famous image: the diminutive rapper wearing a leopard-print bikini and a fur-lined robe and squatting with both legs opened. Plastered around New York City, the soft-core promo had pedestrians doing double takes. In 1996, the image incited parental debates over whether the rapper was destroying the moral fabric of the country. The TV show Rolanda, hosted by Rolanda Watts, aired an episode titled “Is Lil’ Kim sexualizing our children?” “The poster is vulgar and I think it misrepresents Black women,” said a young woman on the daytime show. “She made people feel like that’s all we about. That’s all women are about. Showing our body,” said another.

Behind the salacious visual and lyrics about diamonds, stilettos, and fellatio, Kimberly Jones was a young woman trying to exert her power in a man’s world. “Lil’ Kim is what I use to get money,” she explained of her stage persona to the Washington Post, “a character I use to sell my records.” The rapper was born in Bedford-Stuyvesant, Brooklyn, on July 11, 1974. Following her parents’ divorce, she moved to an all-white neighborhood in New Rochelle, New York, where she was teased and bullied for not looking like everyone else. Eventually, she returned to Brooklyn to live with her volatile father, whom she described as violent and verbally abusive. One incident in particular was the turning point in how she would frame her self-image in adulthood: He called her a “bitch” and “whore” for liking a boy when she was thirteen. “If he hadn’t said what he said to me, I probably would have stayed a virgin until I was twenty-one. But after that I rebelled.” By fourteen, Kim left the house and men became her lifeline as a means of survival and self-worth.

At seventeen, she met The Notorious B.I.G. while rapping in their neighborhood. “As far as the neighborhood, they thought it was fly. They thought it was hot!” she remembered of her verse. He became her great love and masterminded her career. He coached her on the mechanics of rap, teaching her about how to control her flow and cadence, and encouraged her to use a softer, more feminine voice. He selected the photo that solidified Kim as rap’s sex kitten. “He threw the negatives on the table and pointed to the one with my legs open and said, ‘That’s the one right there,’” she said to XXL. Kim was the standout member of Junior M.A.F.I.A., a collective of local rappers mentored by Biggie, and exuded a natural star quality in the group of guys. She dropped song-stealing verses on “Get Money” and “Player’s Anthem” that displayed a razor-sharp delivery and risqué bars, like pulling out a gun on her cheating lover (while wearing Armani suits and Chanel lime boots). Many rap fans believed that Biggie wrote her rhymes — they were shocked that a girl could go so hard — but Kim refuted those claims and pointed to several hits created on her own after The Notorious B.I.G. was killed in 1997.

Kim harnessed the power of her image despite ongoing criticism that she was too raunchy. “What makes me any different from a model?” she asked on BET Talk with Tavis Smiley. “What makes me any different from Madonna?” Despite this outward confidence, the rapper internally suffered from body image issues and the pressure to live up to Anglocentric beauty standards. “I have low self-esteem and I always have,” she told Newsweek. “Guys always cheated on me with women who were European-looking. You know, the long-hair type. Really beautiful women that left me thinking, ‘How I can I compete with that?’ Being a regular Black girl wasn’t good enough.” Many speculated that Biggie’s relationships with singer Faith Evans (whom he cheated on with Kim) and rapper Charli Baltimore, both fair-complexioned and blond, compounded this insecurity. Despite naturally striking eyes, full lips, and a heart-shaped face accented by a beauty mark, she embarked on a long transformation into what appeared to be a living Barbie doll. She was one of the first hip-hop artists to allegedly undergo multiple plastic surgery procedures, including breast implants and liposuction.

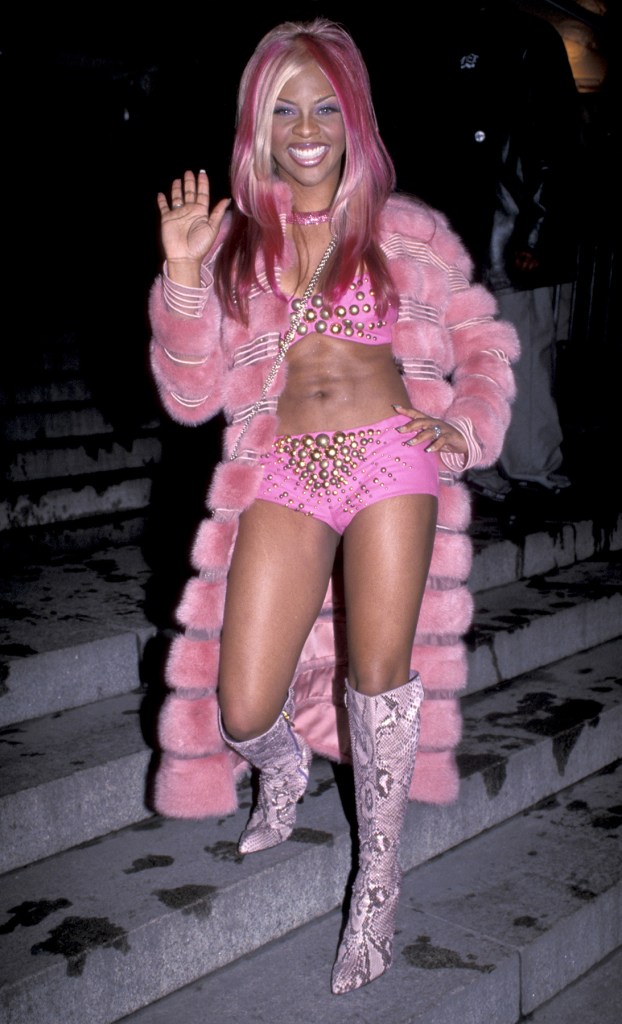

Lil’ Kim’s willingness to be a shape-shifter made her an exciting fashion muse. She had close relationships with designers and called Donatella Versace, Marc Jacobs, and Alexander McQueen her personal friends. “Donatella is my girl. We’ve loved each other from the moment we first saw each other,” said Kim. The pair were seen schmoozing as early as the Versace “Versus” fashion show in March 1998. The next year, Kim was the first rapper at the Met Gala as a guest of Versace, and only Kim and Sean “Puffy” Combs, who attended with girlfriend Jennifer Lopez, represented hip-hop on the red carpet. Kim’s interpretation of the “Rock Style” theme was a ghetto-fabulous homage to hot pink: a bespoke mink coat over a studded bra and hot pants. She accented the look with a two-toned pink ombre wig and snakeskin boots. It was a bold choice among the boring gowns and demure looks on the red carpet. Vogue lauded the outfit, stating that “it helped to kickstart the trend for fearless and body-conscious style on the Met Gala red carpet.”

Lil’ Kim and her rap contemporaries in the late ’90s and early aughts — Foxy Brown, Eve, Trina, Charli Baltimore, Vita, Amil — rejected the gender norms of their predecessors. Many women in hip-hop in the Eighties and early Nineties assumed the clothing of men — baggy jeans, loose shirts, and menswear — as a way to fit in, protect themselves from sexual harassment and unwanted advancements, and to garner respect. MC Lyte released the first solo album by a female rapper titled Lyte as a Rock in 1988. On the album artwork, Lyte was fully covered in a sweatsuit and hanging with the guys while a woman in a miniskirt and red heels was shunned to the side. Lyte was the serious rapper, not to be confused with some random groupie. Queen Latifah wore African outfits befitting her regal name, like headdresses, Africa medallions, and dashikis. “By wearing African clothes, African accessories, not only am I supporting my African brothers and sisters who have these businesses, but it brings me closer to my ancestors,” she said in 1989. “I just feel inner power. Fashion is power, y’all!”

But to Kim’s generation, rap credibility didn’t require stripping away or downplaying femininity. Women leaned in to their beauty and leveraged the male gaze. Musically, they were sex-positive trailblazers who rejected the standard Madonna-Whore Dichotomy, where women were either chaste and “good” or promiscuous and “bad.” If men could rap about “bitches and hos,” they could rap about their sexuality. Furthermore, these artists saw how seduction could be an asset: Lil’ Kim’s “How Many Licks?” was an anthem for cunnilingus. Foxy Brown titled her debut album Ill Na Na, which was also a slang term for her sexual prowess. Trina called herself “da baddest bitch.” And Amil warned men in “Can I Get A . . .” that she stayed in “the Gucci name” and she wouldn’t entertain any man who couldn’t afford her. Female rappers garnered female fan bases who finally felt that they were being represented. They also appealed to men who tuned in because these artists looked hot — and ended up staying because the music was too.

David LaChapelle turned Lil’ Kim into the epitome of sex and luxury. In 1999, the fashion photographer known for his colorful, exaggerated pop art lens shot the rapper completely naked — save for Louis Vuitton logos airbrushed on her skin — for the cover of Interview magazine. “When I did that image, it was about the skin as a luxury item,” said LaChapelle. The next year, he shot Kim and Donatella Versace along with Missy Elliott and Rose McGowan for Interview. The photos displayed how comfortable and happy Kim and the designer were with each other. They were nearly identical, with long, flat-ironed blond hair, perky noses, and fox eyes. In one look, Kim held a glass of champagne in one hand, and her other rested on the designer’s chest. The two seemed to be in their own little world.

Kim and Donatella had more in common than being famous platinum blondes who loved fashion. Their origins were worlds apart, but both came from humble beginnings and understood what it was like to be self-made. They were strong women in male-dominated professions. And most of all, they shared the connection as survivors who had to carry on the larger-than-life legacy of the men they lost.

Ron Galella/Ron Galella Collection/Getty Images

In a career of memorable looks, Lil’ Kim’s most famous was when she arrived at the 1999 MTV Video Music Awards (VMAs) in a lavender sequined jumpsuit with her left breast fully exposed except for a strategically placed pastie that kept censors from having a total meltdown. This was still basic cable. Missy Elliott helped conceive the idea when she jokingly told stylist Misa Hylton: “If I was Kim I would always just have one titty out and be like, fuck it.” Elliott was a fashion rebel herself after she put on an inflatable plastic bag suit in her music video for “The Rain (Supa Dupa Fly)” in 1997. “I loved the idea of feeling like a hip-hop Michelin woman. I knew I could have on a blow-up suit and still have people talking. It was bold and different,” Elliott said years later. The look by June Ambrose challenged the paradigm of female body positivity in rap, decades before the term was popularized.

For Kim’s VMAs look, Hylton used Indian bridal fabric — what could originally be for a lehenga or saree accented with traditional sparkles and shimmery appliqués resembling a peacock’s plumage — to create the fitted one-piece suit. The front of the suit featured an asymmetrical scalloped collar and flared sleeve and the look was finished with a matching purple wig, a diamond ring, and mauve lipstick. But of course, no one could pay attention to anything but Kim’s exposed breast. Even Diana Ross grabbed and jiggled it onstage — five years before Janet Jackson’s infamous Super Bowl “wardrobe malfunction” — and put Lil’ Kim in the pop culture hall of fame. Kim laughed at what became colloquially known as “the boob incident.” “I think it was more of a friendly, ‘Oh my God! You look sexy, girl, but do you know you have a boob hanging out?’”

Lil’ Kim was hip-hop’s premier fashion influencer and that’s who Kimora Lee Simmons enlisted to help launch Baby Phat. In 1999, Kimora started her brand with bedazzled logo T-shirts that she gave to Kim and supermodels Naomi Campbell and Christy Turlington to wear. Baby Phat was originally supposed to be a spin-off of Phat Farm, Russell Simmons’ line of T-shirts, argyle sweaters, polos, and knits founded in 1992, but in women’s sizes. “I would never wear this,” Kimora said, looking at a shirt. The former supermodel, who was eighteen years younger than her husband, wanted something more appealing than the uninspired blueprint. “I didn’t want to wear a football jersey from a man. That was not what I wanted in the sense that it was like your boyfriend’s clothes, like his jerseys,” she said.

Baby Phat designer Kimora Lee Simmons and her daughters walk the runway during her Baby Phat Fall 2005 show as part of Olympus Fashion Week at Skylight Feb. 5, 2005, in New York City.

Fernanda Calfat/Getty Images

Kimora had an instinct for clothing. She had been walking European runways since the age of thirteen. She knew about fit, cut, and fabric, and understood a woman’s body. She came on as head designer of Baby Phat and created a line with herself as the underserved demographic in mind. “I was paying homage to the feminine form, body, and shape, and the references that I was using, the materials, the finishings, the metals and so on and so forth.” She wanted her consumers, young women of color like her, to feel sexy and confident. Baby Phat’s “baby tee” was a fitted T-shirt that hugged the shape of its wearer with the brand’s dia-manté feline logo. Baby Phat jeans were the other tentpole of the brand, with stretchy fabric accentuating the derrière — a decade before it was mainstream — instead of flattening it like most other denim lines. “I had the best jeans in the world,” Kimora bragged.

Kimora’s life as a hip-hop socialite, which she described as a “never-ending whirlwind,” was ingrained into the DNA of Baby Phat. As the only Black and Asian woman heading a luxury fashion line, she bottled and sold the essence of “fabulosity” (also the title of her empowerment book). The New York Times described her as “a flamboyant ex-model with the proud carriage of a Masai warrior and the flirtatious charm of a geisha” (a regrettable reference). She could be seen dealmaking on her pink Baby Phat–bejeweled Motorola flip phone. She also opened up her personal life, something most designers kept private, and made it part of her brand. Baby Phat ads starred Kimora and adorable daughters Ming Lee and Aoki in various fantastical but intimate setups. They could be seen playing in their expansive mansion while a maid watched on or jumping into a Rolls-Royce for afternoon tennis. Kimora represented a lifestyle and made fans feel like they were a part of it.

Baby Phat was on trend with the Y2K fashion of the aughts (low-rise jeans, baby tees, bedazzled logos, velour, and bare midriffs). The brand was visibly more inclusive than its contemporaries Juicy Couture, True Religion, and Ed Hardy, which served a very specific rail-thin white archetype. Not everyone looked like the It girls in Teen Vogue or Laguna Beach, like Paris Hilton, Britney Spears, or Lindsay Lohan. In contrast, Kimora had gorgeous multiethnic features, shiny hair, and feminine curves. As an Indian teenager in the Midwest who didn’t look like anybody else — and was always called “exotic” — Kimora represented everything that I wanted to be.

“I want to be a role model before being a fashion model,” Kimora said. She was an early proponent of inclusivity by hiring diverse models and executives, vendors and partners. Diversity was present in every Baby Phat fashion show during New York Fashion Week both on and off the runway. In 2000, Lil’ Kim walked the lingerie show in a sheer bikini — with the cat logo naughtily placed over her bottom half — under a fur coat and diamond crucifix chain. For the 2003 show, supermodels Carmen Kass and Eva Herzigová wore big hoop earrings and even bigger hair as they modeled denim bustiers, shiny lamé capris, and wraparound tops that let more than one nip slip through. It was a celebrity scene and the paparazzi were there to capture it. Celebrities flocked to the front row. “It’s stylish. It’s sexy. I think that’s what’s hot about it,” said Aaliyah. “I’m here to support Kimora . . . and to see some pretty women,” added Roc-A-Fella Records founder Dame Dash. Rapper Cam’ron told me that he debuted his outrageous baby-pink fur jacket and hat at the 2003 show specifically hoping that the Page Six gossip column would run him in their celebrity sightings the next day. And they did.

In 2004, Russell Simmons sold his fashion portfolio, which included Baby Phat, to the clothing producer Kellwood for $140 million. Kimora remained on as “principal creative arbiter” and eventually became president of Baby Phat in 2006. She took a page from hip-hop’s multihyphenate playbook and became one of the few supermodels turned fashion moguls.

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.