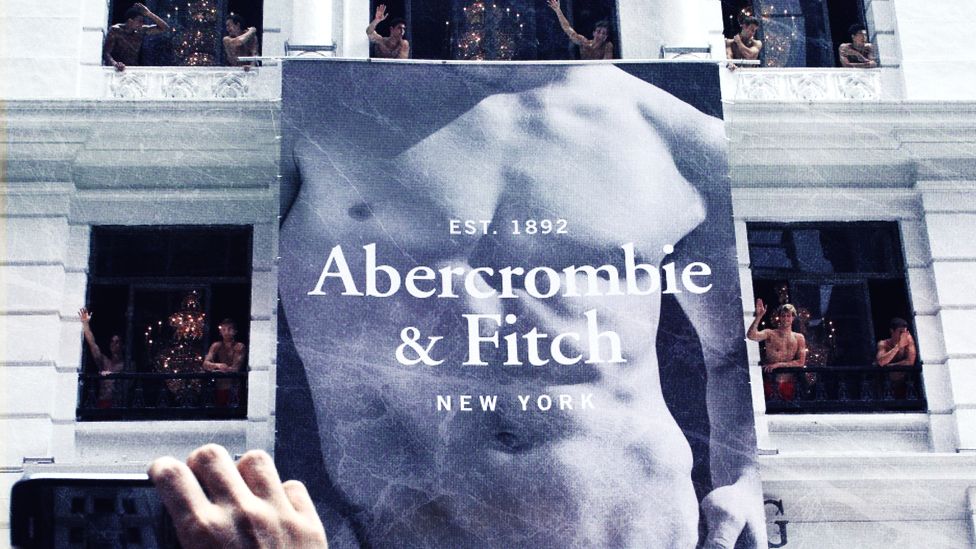

If you were an American teen or pre-teen in the early 2000s, you knew Abercrombie & Fitch.

Whether you loved or hated it, the brand was everywhere – its glossy adverts featuring low-cut jeans and graphic tees, its pungent cologne, its loud and poorly lit stores that anchored mainstream malls around the US.

And if you did love it, Abercrombie was the entry point to a particular type of all-American cool, a preppy utopia for the young and thin.

“They were selling the most popular people in class – the quarterback and the head cheerleader,” says psychologist and author Cooper Lawrence.

This particular version of Abercrombie came to life under the guiding hand of CEO Mike Jeffries, who stands accused of exploiting men for sex, in a BBC investigation.

During his two decades in charge, Mr Jeffries turned the brand into a cultural phenomenon and took it into the retail stratosphere. But he also oversaw its downfall, resigning in 2014 amid a cloud of controversy over allegations of racial discrimination and a toxic work culture.

In 1992, when Mr Jeffries officially took over, Abercrombie was a 100-year-old company with a reputation for safari wear. A few years earlier, the company had been bought by retail magnate Les Wexner, who moved its headquarters to Columbus, Ohio, and handed control to Mr Jeffries.

The Californian had a clear, if exclusionary, vision.

“In every school there are the cool and popular kids, and there are the not-so-cool kids. Candidly, we go after the cool kids. We go after the attractive, all-American kid with a great attitude and a lot of friends,” he told Salon in a now-infamous 2006 interview.

“A lot of people don’t belong [in our clothes] and they can’t belong. Are we exclusionary? Absolutely.”

Watch Panorama’s The Abercrombie Guys: The Dark Side of Cool, on BBC iPlayer now and on BBC One on Monday at 21:00 BST.

Listen to the podcast series, World of Secrets: Season 1 – The Abercrombie Guys, available on BBC Sounds from 21:00 BST.

The Abercrombie Guys: the Dark Side of Cool will be releasing in the US on October 6 on BBC Select, available to audiences via Amazon Prime Video Channels, the Apple TV app and The Roku Channel.

And throughout Mr Jeffries’ reign, Abercrombie’s every detail seemed to deliver on that promise.

“Sexy clothes on sexy people was what they were after,” Katie Hertert, an assistant to Mr Jeffries from 2004 to 2006, told the BBC.

“The merchants and designers and everybody were trying to get in front of Mike to have him say, ‘Yes, this is sexy.’ That was entirely the goal.”

Shirtless male greeters stood sentry outside stores, beckoning shoppers inside a nightclub-dark interior, with the A&F Fierce cologne liberally hosed across the racks of clothes – intentionally distressed denim, cotton polo shirts and pullovers, all branded with the ubiquitous moose.

Abercrombie advertisements were shot primarily by Bruce Weber, the celebrity photographer. His signature image for the brand featured black-and-white photographs of partially dressed young people. Jamie Dornan, Channing Tatum, Olivia Wilde and Jennifer Lawrence are all former models for the brand.

Stores did not sell clothes for women larger than a US size 10 (roughly a UK size 14) until 2014, after Mr Jeffries had left the company.

“Abercrombie was the deification of this extremely conventional, preppy, affluent, ultra-white lifestyle that really had not been considered all that cool [earlier in the ’90s],” said Maureen Tkacik, a journalist for The Prospect who has reported extensively on the brand.

Getty Images

The apparently casual style of store employees was the product of a rigid dress code.

According to an employee style guide from Mr Jeffries’ tenure, denim shirts were to be worn with three buttons open, skinny jeans were to be cuffed at 1.25 inches and hairstyles had to be “neat, clean, natural, kempt and classic”.

Nearly every part of Abercrombie and its image bore Mr Jeffries’ fingerprints.

Employees at Abercrombie speaking to US media described Mr Jeffries as a reclusive, mercurial and obsessive boss, prone to superstitious rituals. But, above all, colleagues said he was dedicated to the brand. Even corporate employees were encouraged to wear Abercrombie branded clothing to make their CEO happy.

Mr Jeffries’ business strategy proved lucrative. From 1994 to 1999, sales jumped $165m (£135m) in 1994 to $1.04bn. At its height, Abercrombie had more than 1,000 stores in the US, Canada and the UK.

But about 10 years into Mr Jeffries’ tenure, Abercrombie’s shine began to fade – in large part due to the exclusionary practices that the CEO had championed.

In 2002, Abercrombie faced protests over a line of Asian-themed T-shirts replete with racist stereotypes, including men in rice-paddy hats and the words “two Wongs can make it white”. It was quickly recalled.

One year later, the company faced a class action lawsuit brought by several thousand former employees and job applicants, who alleged the company had discriminated against African Americans, Latinos and Asian Americans in its hiring and advertising.

According to the plaintiffs, Abercrombie turned down racial minorities for sales positions, relegated them to backroom jobs and had their hours reduced when managers decided their look was not “Abercrombie enough”.

The company settled for $40m, but did not admit wrongdoing.

Years later, in 2015, Abercrombie would argue before the Supreme Court that it was legal to deny employment to a Muslim woman with a headscarf because the garment violated its “look policy” which banned hats. Abercrombie lost 8-1.

“Abercrombie was exclusionary, it wasn’t just exclusive,” said Cooper Lawrence. “Abercrombie & Fitch didn’t figure that out on its own, they had to get sued.”

Through a 2023 lens, it’s shocking, she said.

By the time Mr Jeffries stepped down in 2014 as CEO and chairman, with a multi-million retirement package, the company had also lost its financial momentum. Sales and stocks were falling.

Related Topics

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.