Although she wasn’t able to study for a degree at the University of Oxford, Sarah Acland benefited from being immersed in the university community where her father, Henry, was an influential professor as well as a good friend of the writer and art critic, John Ruskin.

The two men had worked together on the designs for the University Museum building (known today as the Natural History Museum) which fused the fascinating discoveries of Victorian scientists about the role of colour in the natural world along with Ruskin’s love of colourful Gothic architecture.

In the 1860s, Ruskin agreed to become teenaged Sarah’s drawing tutor and in their lessons, imparted his beliefs on the power of colour to unlock the sacred beauty of nature.

In his manual Elements of Drawing he wrote ‘If ever any scientific person tells you that two colours are “discordant”, make a note of the two colours, and put them together whenever you can.’

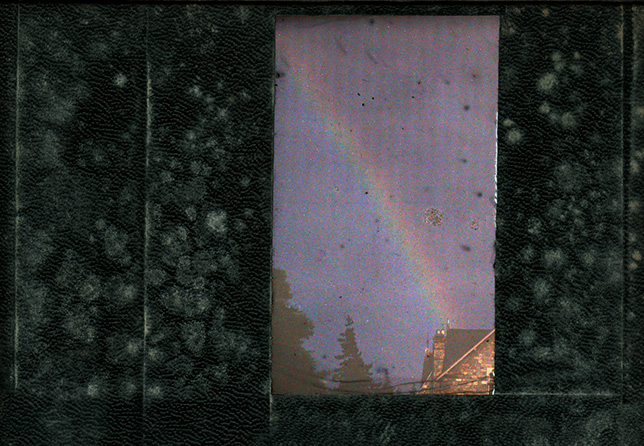

Sarah’s early work is full of Ruskinian ‘truth to nature’ naturalism, but she carried his lessons on colour forward as she forged a career in photography.

In 1894, Acland joined the new Oxford Camera Club as its first female member, later becoming vice-president. Her most important contribution to the field of photography was her work using the Sanger Shepherd method, which had been invented just before 1900.

The Sanger Shepherd process set a pathway for future colour photography, followed notably by Kodak’s dye-transfer process of the 1940s.

Instead of heeding Ruskin’s suggestion to combine two ‘discordant’ colours, this process involved taking three separate exposures on one plate – each through a different chromatic filter – before printing the red negative onto glass, and then green and blue negatives onto transparent celluloid that was then stained yellow and pink. These were combined onto one lantern slide which could either be shown through a projector or printed on paper.

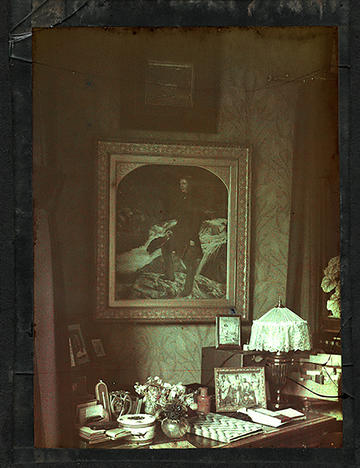

Acland paid tribute to her great teacher using another early colour photography technology, the autochrome. She owned Millais’s celebrated portrait of Ruskin and photographed it in her study at 40-41 Broad Street in the mid-1910s.

Using all of the colour technology at her disposal, she tried to capture the portrait’s colours as accurately as possible, in accordance with Ruskin’s truth to nature beliefs.

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.