“All right, we’ve got a small house… but we’ve got a big bloody heart, I tell ya.”

Danny Bergara, former Stockport County manager

They make their way out of a dressing room decorated with motivational buzzwords — ‘Intensity’, ‘Enjoyment’, ‘Work-rate,’ in navy-blue capitals on white walls — and head along a stud-marked path to the training pitches where Roberto Mancini plotted Manchester City’s first Premier League title.

Advertisement

For the players of Stockport County, there is nothing new about living among exalted company.

Over the next field, past the riding school and the electricity pylons, Manchester United’s training ground is tucked behind the row of trees their then manager, Sir Alex Ferguson, had planted to keep out snoopers.

This is where City used to train. Look closely and you can see “the Hill of Hell”, the steep, grassy mound put in by Mancini, where his players would be forced to complete punishing military-style runs.

And now, a decade on, the players of Stockport, three divisions below the Premier League, are doing wonderful things on a smaller piece of the Carrington district of Manchester, where a special story is being shaped at their own training headquarters.

Dave Challinor’s team have just won their 12th league game in a row, equalling a League Two record. They have more points than any club in England’s top four divisions (41) and have also outscored everybody (39).

Stockport’s upward trajectory — they are aiming for a third promotion in six seasons — is one of football’s feel-good stories, given it is only a few years since they were sleepwalking towards potential oblivion.

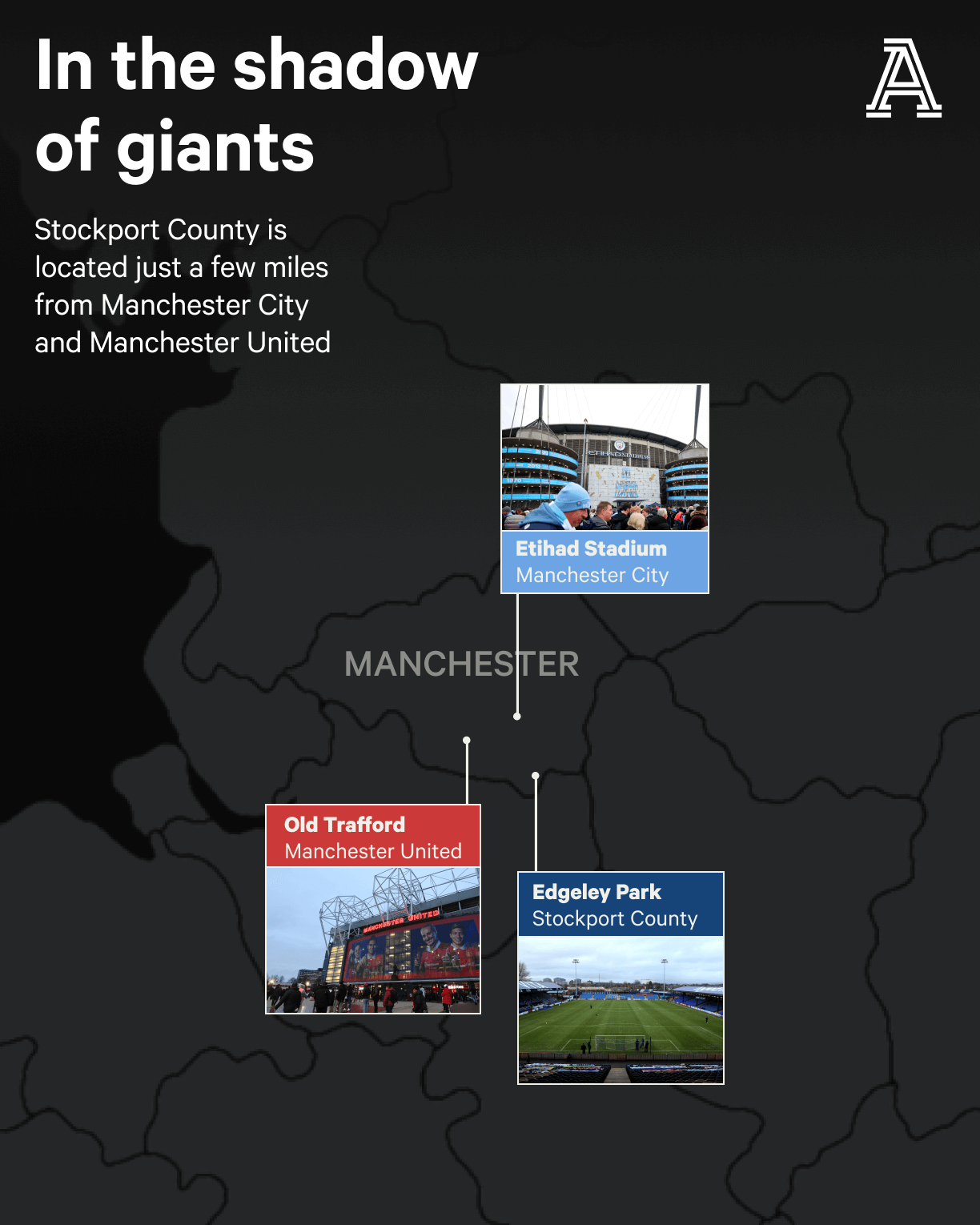

But it feels like even more of an achievement bearing in mind the challenges of living in the shadow of the two giants just up the road.

Their Edgeley Park ground is six miles from the Etihad Stadium, the scene of City’s reinvention as the best football team in the country, even Europe. Old Trafford, where United used to hold that honour, is not much further on the other side of Mancunian Way.

Every Stockport fan of the last 25 years was brought up hearing stories about what happened in the 1997-98 season, when their club finished eighth in what is now the Championship — their highest-ever league position — as neighbours City, then auditioning to be known as English football’s Slapstick XI, fell through the same division’s trapdoor into the old Third Division.

Advertisement

Yet there were also times when Stockport strayed dangerously close to slipping off the radar altogether before Mark Stott, a local businessman, launched the 2020 takeover that changed everything. In the words of club president Steve Bellis, it was the day Stockport “won the lottery”.

The Athletic has spent two weeks observing, close-up, the inner workings of this renascent club. We have watched Challinor’s training sessions. We have sat through team meetings, dined with the players, met the staff, seen the plans.

But if you want to appreciate this story fully, you also need to know where Stockport have been, and how wild and scary that ride became. You have to understand why Bellis recalls a time when “the soul had been ripped out of the place”.

More than anything, you have to go back to the years in the previous decade when they were playing regional, part-time football in the sixth-tier National League North; days when their goalkeeper, Ben Hinchliffe, doubled up as a long-distance lorry driver.

Everything feels so different now.

Stockport are six points clear at the top of League Two 18 games into the 46-match season. There are plans to redevelop three sides of Edgeley Park, doubling its capacity to 20,000. A new training ground will also be built, with enough space to accommodate the academy and women’s teams.

Last season, Stockport lost the play-off final on penalties — they were six minutes from promotion to League One before Carlisle United equalised. As things stand, they are in a strong position to go one better and be one of the three sides to go up automatically. But Stott, a property mogul, wants to go even higher.

His aim is to take Stockport back to Championship level, maybe even the Premier League.

“Stockport fans of a certain generation will always fondly remember Brendan Elwood’s time as chairman in the 1990s,” says Bellis. “But Mark is like Brendan Elwood on steroids. I have never been more excited about the future of Stockport County than I am today. And I have been involved for over 40 years.”

“Stockport is the new Berlin.”

Luke Una, Manchester DJ

Advertisement

A recent feature in the UK’s Times newspaper — “Why Stockport, Greater Manchester, is one of the best places to live” — named it among the 12 most desirable towns in England for first-time homebuyers.

“Stockport has engineered a remarkable reinvention from a standard former mill town into a funky, family-friendly alternative to Manchester’s Northern Quarter,” the feature read. “This is where the avocado-brunching millennials move when they have a Lejoux pushchair and are faced with the school run but still want to live a fashionable life.”

It is just a pity, perhaps, that Stockport has been let down in the past by town planners building over the River Mersey, running a motorway beneath what is an otherwise beautiful viaduct and spending £45million ($56.1m at the current exchange rate) on the Red Rock leisure hub, which in 2018 was named as Britain’s ugliest building.

Stockport’s beautiful viaduct, with the M60 motorway underneath it (Anthony Devlin/Bloomberg via Getty Images)

Stockport has not always had such kind reviews as the one in the Times.

In 2005, it was ranked 12th in a book called Crap Towns: The 50 Worst Places To Live In The UK, described as a “hellhole” where “entertainment includes being glassed in one of the many pubs” or “avoiding being stabbed on the infamous 192 bus”.

These days, however, Stockport is on the up.

New developments are taking shape as part of a £1billion regeneration programme.

The skyline is changing in the town that gave us current Manchester City and England forward Phil Foden, three-time Wimbledon tennis champion and fashion icon Fred Perry, indie band Blossoms and Strawberry Studios, where Paul McCartney, Joy Division and The Stone Roses all recorded.

Arriving by rail, visitors are welcomed by a sign in neighbouring bar Bask proclaiming (with no asterisks), “Stockport isn’t s**t.”

Edgeley Park has also been rejuvenated with a level of care and attention that simply did not exist when Simon Inglis, the author and historian, wrote in his 1987 book The Football Grounds Of Britain that it “seemed on its last legs”.

Advertisement

Outside, a fan zone has taken over most of the car park, with a stage, live music, street-food stalls and the statue of Bergara — tracksuit top, kind eyes, cap raised — looking on approvingly, as a legendary manager of the past.

Edgeley Park has been spruced up (Alex Livesey/Getty Images)

Inside, through the glass doors, past vases filled with wild flowers and the cheery “How are ya?” welcome, almost every part of the ground has had a makeover. Formerly dowdy function rooms with peeling paintwork and damp, threadbare carpets have been transformed into swish banqueting suites.

What was once a dreary corridor is now a club Hall of Fame, lined with framed photographs of popular ex-players. Bars have been upgraded. The small details matter, right down to the quality of the pies sold to fans on matchday, putting in a postbox for fan suggestions and installing a pizza oven beneath the Cheadle End, the part of the ground where most of the matchday noise is generated.

These are the streets where the young Foden honed the precious magic that led him to City, earned him the nickname of The Stockport Iniesta and made him, at the age of 23, a five-time Premier League champion. His former house, 117 Grenville Street, is barely two minutes’ walk away. And if you are wondering why his hometown club missed out on a player who was virtually on their doorstep, there is a simple answer.

“At the time he started catching people’s eyes, we didn’t have an academy system,” says Bellis. “We had scrapped our centre of excellence because it was too expensive to run. The structure of the whole club was collapsing and the academy was seen as a cost, not a benefit.”

Phil Foden’s old house in Stockport (Daniel Taylor/The Athletic)

Stockport’s descent through the divisions from that late-1990s high is a long, complex story, both in the boardroom and on the pitch, featuring back-to-back relegations to tumble out of the Football League for the first time in their history in 2011 and, worse, another relegation, this time out of the Conference, two years later.

Stockport’s first match in the sixth tier, northern section, was a 4-1 home defeat against Boston United. The next four games did not yield a single win. Ian Bogie, their eighth manager in three years, was so emotional, he resigned on the pitch.

Advertisement

“Some of our younger fans have known nothing, until the last couple of years, apart from non-League football,” says Jon Keighren, then a club director. “But there are many others who can remember when City were playing Macclesfield in League One while we were in the Championship.

“We were going to all these great old stadiums — Selhurst Park, Molineux, the Stadium of Light — and, very naively, I thought it was always going to be like this.

“Then you blink and the next thing you know you are playing Vauxhall Motors, which is not even a place — it’s literally a car factory with a pitch. Or you are on your way to North Ferriby, which is basically just a village with some allotments. That was probably our darkest moment. And we lost at Vauxhall Motors, by the way.”

Keighren, also a broadcaster who has been commentating on Stockport games for a quarter of a century, was invited to join the board the day after the club dropped out of the National League. To begin with, however, he was unsure.

“You don’t want to be tainted by failure. But you can’t just stand on the sidelines complaining, ‘This is s**t, we can’t carry on like this’ and not actually do something about it. I said I would help out for six months and I ended up being on the board for seven years.

“I don’t miss those days of worrying, ‘How are we going to pay the wages? How are we going to pay the training ground rent?’. We had no choice but to go part-time. It was horrible but we’d have gone bust otherwise.”

Unable to afford a proper training ground, Stockport had to pay for hourly rental slots on local pitches, including a regular booking at St Paul’s, a Catholic school in Wythenshawe, south Manchester. “One night, the players were trying to do some set-piece practice, on a pitch that wasn’t even the right size,” says Keighren. “Suddenly this fella marches on: ‘Right, eight o’clock, you’re off!’ Wythenshawe under-11s were about to go on.”

Advertisement

So this is the context when drinkers in the Royal Oak, the Prince Albert, the Armoury, Sir Robert Peel, the Jolly Crofter, the Pineapple and all the other pubs near Edgeley Park reflect on the club’s resurgence and compare their story to that of League Two’s fourth-placed side Wrexham, minus the Hollywood A-listers and the publicity machine generated by Ryan Reynolds and Rob McElhenney.

As neighbours City reinvented themselves post-takeover as English football’s new powerhouse, Stockport’s fans had to form new rivalries with local teams such as Stalybridge Celtic, Hyde United, Altrincham and Curzon Ashton.

FC United of Manchester, the breakaway club formed in 2005 by Manchester United supporters protesting Malcolm Glazer’s takeover at Old Trafford, appeared on the radar too. In one FA Cup tie against them, Stockport led 3-0 only for it to finish 3-3. In the replay, FC United went down to nine men via two red cards in the first half. Full-time score: FC United 1, Stockport 0.

“We also went to Colwyn Bay, where there were only three stands,” says Keighren. “Our fans treated it as a day at the seaside. They broke into a farmer’s field and, one by one, started rolling down the hill. All they had left was gallows humour.”

Stockport Maidenhead United in the National League in 2020 (Richard Heathcote/Getty Images)

“It’s a bloody holiday resort where we used to go as kids,” Bellis recalls of that same trip to the Welsh coast. “When they came to Edgeley Park, their players were taking selfies in front of the Cheadle End because they had never played anywhere so big. And, bloody hell, they beat us, too.”

As the indignities stacked up, training sessions had to be switched to evening slots, twice a week, because so many of the players had day jobs. Jordan Keane doubled up as a dog-walker. Danny Lloyd, the team’s top scorer, sold bins. Matty Warburton, a midfielder, worked as a PE teacher.

Hinchliffe’s lorry had the name of BAKO North Western emblazoned across its side, delivering bakery products as far afield as Leamington Spa in the Midlands and Barrow in the far north of England. “I was on 4am starts,” says the goalkeeper, now ninth on Stockport’s all-time list of appearance-makers. “Even if we had played a night match, I had to be up at 3am. I’d get home in the afternoon, have half an hour’s sleep and then I was out to training.”

Advertisement

Once every season, Hinchliffe has to miss a match because of his job. “Every lorry driver has to take a CPC course (Certificate of Professional Competence) in February or March. By law, there was no way out of it. Unfortunately for me, it was always a Saturday. The team would be playing while I was sitting in a classroom, checking the score with my phone under the table.”

Stockport spent six years among the puddles and potholes of National League North and, in that time, the only constant was the loyalty of the 3,000 or so fans who kept coming back, hoping for better times. Those fans know what it is like to be thrashed 6-1 at Alfreton Town. They know how it feels to lose 4-0 at home to AFC Fylde. They haven’t forgotten Stockport having a run of away fixtures at Telford, Leamington, Gloucester, Guiseley and Solihull Moors — and losing them all.

One takeover bid was proposed by a Chinese consortium which attracted suspicion when asked to supply proof of funding. It came in the form of a fax, with a Barclays Bank letterhead, claiming it had exactly $1,000,000,000 in its account.

“We had around 20 offers but not all of them were serious and the vast majority fell apart when we asked for proof of funding,” says Keighren. ”We had to be patient. We had to wait for the right deal. And thank God we did because then, of course, Mark Stott came along.”

“Crisis has become such a way of life at this club, we wouldn’t know otherwise. It is the norm and has been for years.”

Stockport blogger Adrian Caville, 2013

On the walls of the boardroom, there is a row of framed black-and-white photographs to remind everyone of the days when George Best, Manchester United royalty, wore Stockport’s colours.

“It’s amazing how many people on our ground tours say, ‘Wait a minute, did George Best play for Stockport?’,” says Bellis. “We’re proud of the Best connection because it put the club on the map at another time (the mid-1970s) when we were struggling.”

Played For Who?!

George Best at Stockport!

The Ballon d’Or, European Cup and 2 time League Title winner, and Manchester United/footballing icon played 3 games for County in 1975 scoring 2 goals in the 4th division!#EFL #LeagueTwo #SkyBetLeagueTwo #StockportCounty pic.twitter.com/WQzEubAq3m

— League Two Central (@league2_central) June 8, 2022

Along the corridor, through a suite with framed memorabilia for “Go Go Go County”, then up the flight of stairs, a door opens to an executive lounge decorated with more nostalgic pictures.

Advertisement

This is where Stott can usually be found before matches, among a table of guests against the far wall. Stott is not as showy as some men of wealth. He prefers to be low-key and rarely does interviews. But you do not need long in his company to understand his investment is emotional as well as financial.

“For the fabric of a town like Stockport, it’s so important,” Stott says. “It’s a sweeping statement, perhaps, but when a football club is doing well, everything feels better in the entire town. It can make such a difference to the mental health of so many people, going home happy on a Saturday night because their team has won.”

Stott grew up locally, as a City fan, built a property empire, the Vita Group, out of almost nothing and started to think seriously about buying a football club four years ago.

Macclesfield Town, a club half an hour’s drive further south who had been financially shipwrecked, were among the options. Stockport, however, always held more appeal for a man who was raised in Poynton, on the town’s outskirts, and knew the area was brimming with potential.

“There are nearly 300,000 people living in Stockport,” says Stott. “That’s a bigger population than Sunderland. And just look at the size of their club.”

It is true. The borough of Sunderland has a population of 275,000. Other football towns and cities such as Burnley (95,000) and Portsmouth (208,000) have lower numbers. It was staring Stott in the face: get this right and something special could take off.

Even then, however, Stott wanted to make sure he had the right people in place.

One of his contacts had introduced him to Simon Wilson, a one-time Peterborough United academy player who had made a career in football as an innovative thinker, planner and recruiter, including 10 years with Manchester City and the group that launched New York City in MLS.

Advertisement

The two men talked, shared ideas and found common ground. Wilson went away to work on a 30-day analysis. The more they talked, the more they believed they could take Stockport higher than ever before. The takeover was confirmed on January 16, 2020, with a seven-year plan to make them into a high-end Championship club.

“If I had not met Simon and got him on board, I wouldn’t have gone through with it,” says Stott. “We needed his football intelligence or it would have been just an emotional purchase.”

Wilson began his career as a consultant for Prozone, the company that introduced data-led analysis to football. He went to Southampton as one of the sport’s first full-time analysts, then held a number of prominent roles in City’s empire, briefly became Sunderland’s chief football officer and worked as a consultant for, among others, the Premier League, UEFA, Ajax and Leicester City.

His CV, in other words, is elite level, whereas his appointment at Stockport came three days after a 2-0 home defeat to Dover Athletic. Yet he, like Stott, quickly got the bug.

“I’ve realised over time that my strength is building stuff,” says Wilson. “New York City, for example, was a start-up. Mark has a similar mentality. I looked at what he had done and thought, ‘Yeah, we could work together and have some fun’.”

Stott, third left in the directors’ box, and Wilson, second left (James Gill – Danehouse/Getty Images)

In a different era, Stockport’s home fixtures were switched to Friday nights to avoid potential clashes with their more illustrious neighbours’ games the next afternoon. The current regime, though, insist the club’s geography can be an advantage, not a hindrance.

One idea, if they are promoted to League One for next season, is that Wilson will try to attract high-calibre loan signings through his contacts at both City and United.

Then there is the pool of academy players who slip through the cracks at Manchester’s Big Two. “We should be their first port of call,” says Stott. “If we have a great academy, why wouldn’t young kids and their parents want to join us?”

Advertisement

The challenges are obvious when there are more than 20 professional clubs within a one-hour radius. But there is also plenty of evidence that many football fans want something different to the matchday experience the Premier League offers.

“We talked about what we were seeing in the industry and we knew the fans would come back if we got it right and reconnected with the Stockport identity,” says Wilson. “We felt there were enough people who were getting fed up with the Premier League — VAR and all that kind of stuff — and enough families who couldn’t afford tickets.

“We felt we could tap into that. When everything came out about the European Super League (in early 2021), there was another backlash. That was another opportunity for us to show ourselves as a proper community club that is authentic, real, truthful, transparent.”

The result, last season, was Stockport’s highest average attendance (9,108) since 1967 — more than twice what their crowds had been in 2019-20. This season, it is even higher. Season-ticket sales have rocketed from 1,700 to 5,800. Just take a walk around the town’s rather beautiful Market Place and look how many Stockport shirts can be seen. By the end of the season, the expectation is that 15,000 of them will have been sold. It was 1,750 four seasons ago.

“I hear some County fans say, ‘We don’t want City or United fans here’,” says Stott. “But we do, actually. We are going into the schools, trying to grow the club. I drive around the different areas of Stockport and the most exciting thing for me is that, if there are 15 kids playing football (in the street or a park), six of them have County kits on. It’s unheard of.”

“We supported The Stone Roses at Wembley and we’ve played the Pyramid stage at Glastonbury, but it won’t come close to walking out at Edgeley Park.”

Tom Ogden, Blossoms frontman, before their 2019 homecoming gig

And so, just before 3pm on Saturday, the Stockport team emerged from their dressing room, turned down a corridor where the walls list the name of every player in the club’s 140-year history (1,667 of them) and made their way out of the tunnel to become the first fourth-division side since 2002 to put together 12 consecutive victories.

Advertisement

They won 2-0 against Colchester United, taking the lead late in the first half and scoring again soon after the interval. Stockport looked what they are: confident, used to winning, totally committed. They were quick to the ball, strong in the tackle, and played with the authority that Challinor had asked for in a tactics meeting at the training ground the previous day.

Challinor gave his instructions from the back of a cinema-style briefing room. He was clear and concise, playing a series of video clips to sharpen everyone’s focus, explain exactly what he wanted and analyse Colchester’s strengths and weaknesses. “Get on the front foot,” was the instruction, “and then we can hurt them.”

This was the opportunity to see, close up, the tactical expertise that has helped Challinor win four of the last eight League Two manager of the month awards. Everything was couched positively. And he sounded like a manager who completely believed in his players. “We’ve got ourselves in a great position, fellas,” Challinor said. “We’ve shown what’s required to be a successful team. Continue that, get it right, ride the wave of momentum as long as you can. You don’t often get opportunities to equal or break records.”

As a player, Challinor had a couple of seasons at Stockport two decades ago, experiencing the first of their five relegations between 2002 to 2013, and was famed for breaking the world record for longest throw-in, measured at 152 feet (46.34m) in a special challenge set up at Tranmere Rovers, where he played for eight years before joining Stockport.

For Challinor the manager, however, the emphasis is on passing out from the back, dominating possession and playing with a style influenced by Pep Guardiola, Jurgen Klopp and others.

“In possession, out of possession, we want to be on the front foot,” Challinor explains in a quiet moment in his training ground office. “We want to get bodies forward, attack as best we can: ‘Go on, lads, get on the ball and play. And if we lose the ball, win it back as early as we can’. When you look at modern football, right at the top level, that’s what it is, just a watered-down version.”

Challinor has had a big impact on Stockport (George Wood/Getty Images)

That style of football has helped Challinor, two years into the job, record the highest percentage of league wins (62.1 per cent) of any manager in Stockport’s history.

Advertisement

He also has a reputation as a promotion specialist, including three in eight years as manager of AFC Fylde, on the other side of Manchester on the Lancashire coast. Others came at Stockport’s old friends Colwyn Bay, where he started in management, and Hartlepool United in the north east of England, whom he took back into the Football League three seasons ago. And the former centre-half has done it, in Wilson’s words, playing “beautiful football” at a level where it requires a certain amount of courage to employ these tactics.

“The day he was appointed, I knew we’d win the league,” Hinchliffe, who had been part of Challinor’s team at Fylde, says of Stockport’s promotion back to the EFL as champions in 2021-22. “When we were without a manager, I remember telling people, ‘He’s the one’. His promotion CV, from Colwyn Bay to Fylde, Hartlepool and now Stockport, is unbelievable.”

Challinor has a “Champions” scarf hanging in his office and a quote from Sir Alex Ferguson up on another wall: “The experience of defeat, or more particularly the manner in which a leader reacts to it, is an essential part of what makes a winner.” It is there, Challinor explains, because there have been times in the past when his desire to win has made it difficult for him to handle losing.

Stockport train at their Carrington base (Daniel Taylor/The Athletic)

In the players’ lounge, there are pool tables, a darts board, a chess set and a jukebox where the popular selections this past Friday, for reasons unexplained, took the form of Slade, Boney M and a medley of other Christmas songs.

There are two multi-coloured “Forfeit Wheels” the players have to spin if they are guilty of minor infringements. Punishments include paying a £25 fine, dancing for a minute, chatting up a mannequin or playing table tennis with Matt Jansen, the former Blackburn Rovers and Crystal Palace striker who doubles up as the club’s player-liaison officer and unofficial ping-pong champion.

GO DEEPER

Matt Jansen returns for the first time to the scene of the moped accident that changed his life for ever

There is also a good reason why a picture on the wall shows Stockport’s dressing room at Wembley after losing last season’s play-off final in that shootout with Carlisle.

Challinor put it up to remind his players they never want to experience that feeling again. “We know that finishing in the play-offs would be a failure this season,” says Hinchliffe. “We have to get out of the division, then add more quality and take on League One next year.”

Advertisement

Expectations have soared at a club where the annual revenue this season is forecast at £9.1million, up from £1.65m pre-takeover, and the new regime started implementing a “Championship-ready” plan even while Stockport were in the fifth tier.

Incredibly, the club had only six full-time staff when Stott took control. They now have 174.

The new owner has been able to increase the pay structure and Wilson’s expertise in a beefed-up recruitment system should mean they do not have to suffer a repeat of what happened when they were eyeing up a young Jamie Vardy from FC Halifax Town over a decade ago. Vardy’s name had been written on a list of targets on a whiteboard in Edgeley Park’s offices. Paul Simpson, the manager, went to see him play, couldn’t see the attraction and reported back that Vardy’s name should be scrubbed off.

For Stockport, there have been a few awkward moments over the years (Jim Gannon, another former manager, once refused to speak to UK broadcaster Sky TV because his satellite decoder box was broken and nobody had been around to his house to fix it).

These days, however, the only conclusion to draw is that the people in charge are deadly serious when they say their ambition, ultimately, is to establish Stockport among the top 30 clubs in the country.

Stott has also made it clear he wants them to be at the heart of their community, especially when there are parts of Stockport that have a history of social deprivation. The club’s community trust, established as a charity in 2021, has almost 20 people working out of offices at Edgeley Park. All sorts of sporting, educational and philanthropic programmes have been set up to promote better physical and mental health. The aim, says the chief executive Alison Warwood, is to perform a “life-changing role” among priority areas.

And, ultimately, there is a lot to like.

Advertisement

“An American audience will know the story of Wrexham,” says Wilson. “The way they have gone about it is amazing. It’s a new case study but we always say, and this is not to be competitive, ‘Are they building value in Wrexham football club or is the value just in the owners?’. We think we are building value in Stockport County.”

The Danny Bergara statue outside Edgeley Park (James Gill – Danehouse/Getty Images)

At Saturday’s match, the guest of honour was Tony Dinning, a former midfielder who will always be cherished here for a) scoring the winning penalty in a second-tier game against City at their then home of Maine Road in December 1999 and b) impersonating City goalkeeper Nicky Weaver’s celebration from the previous season’s League One play-off final defeat of Gillingham.

Bellis, awarded the presidency in 2020 to recognise his work throughout the wilderness years, recalls another game against City, this one in 1997. It was the first time they had met in the league for nearly 80 years and Stockport — little, patronised Stockport — went three goals up after 29 minutes on the way to a 3-1 home win.

Challinor has his own memories.

“When I came here (as a player) in January 2002, we were bottom of the league (today’s Championship) by a long way and ended up being relegated with the lowest points ever for that level (26). We got relegated at Selhurst Park (against Wimbledon) on a Saturday. Then we played City (at home) on the Tuesday night. We were 1-0 down, against the side that was top of the league and on the way to being champions, and we scored twice in the last couple of minutes. The place was absolutely bouncing.”

Today, this proud old club can look to the future rather than clinging to the comfort blanket of nostalgia.

The crowd on Saturday headed home happy, singing, “County’s going up.”

Beat Newport County away on Saturday and Stockport will hold the League Two record outright with 13 straight victories. Another two after that would make them the first team in the entire history of the Football League, all the way back to 1888, to win 15 matches on the bounce.

Advertisement

Stott looked on proudly from the Edgeley Park directors’ box.

“In 10 years’ time, we will be able to fill a 20,000-seat stadium,” he says, “and it’s going to be a cauldron.”

(Top photos: Getty Images; design: Eamonn Dalton)

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.