It’s so easy to take the world for granted. Sometimes, the best way to see life in all its beauty and strangeness is to imagine the viewpoint of someone seeing it for the first time. That’s the animating perspective of Poor Things, the new film from surrealist Greek filmmaker Yorgos Lanthimos.

Based on Alisdair Gray’s 1992 novel of the same name, Poor Things centers around a young Victorian woman named Bella Baxter (Emma Stone), whose very existence is the result of mad scientist Dr. Godwin Baxter (Willem Dafoe) transplanting the brain of an unborn fetus into the body of a recently deceased adult woman. Since Bella is seeing everything for the first time, the cinematic world around her has to vibrate with the exuberance of discovery. Lanthimos realized that the best way to visually represent her unique way of seeing things would be to make the 2023 version of an old-fashioned Hollywood studio movie.

“From the beginning, I thought that we should build everything, even exteriors, in the studio, so that we had total control of how everything looked,” the Oscar nominee behind The Favourite and The Lobster tells EW. “Using very old-school techniques and aesthetics, paired with the technology that we now have available, seemed like the best way.”

Searchlight Pictures

Dream ‘scape

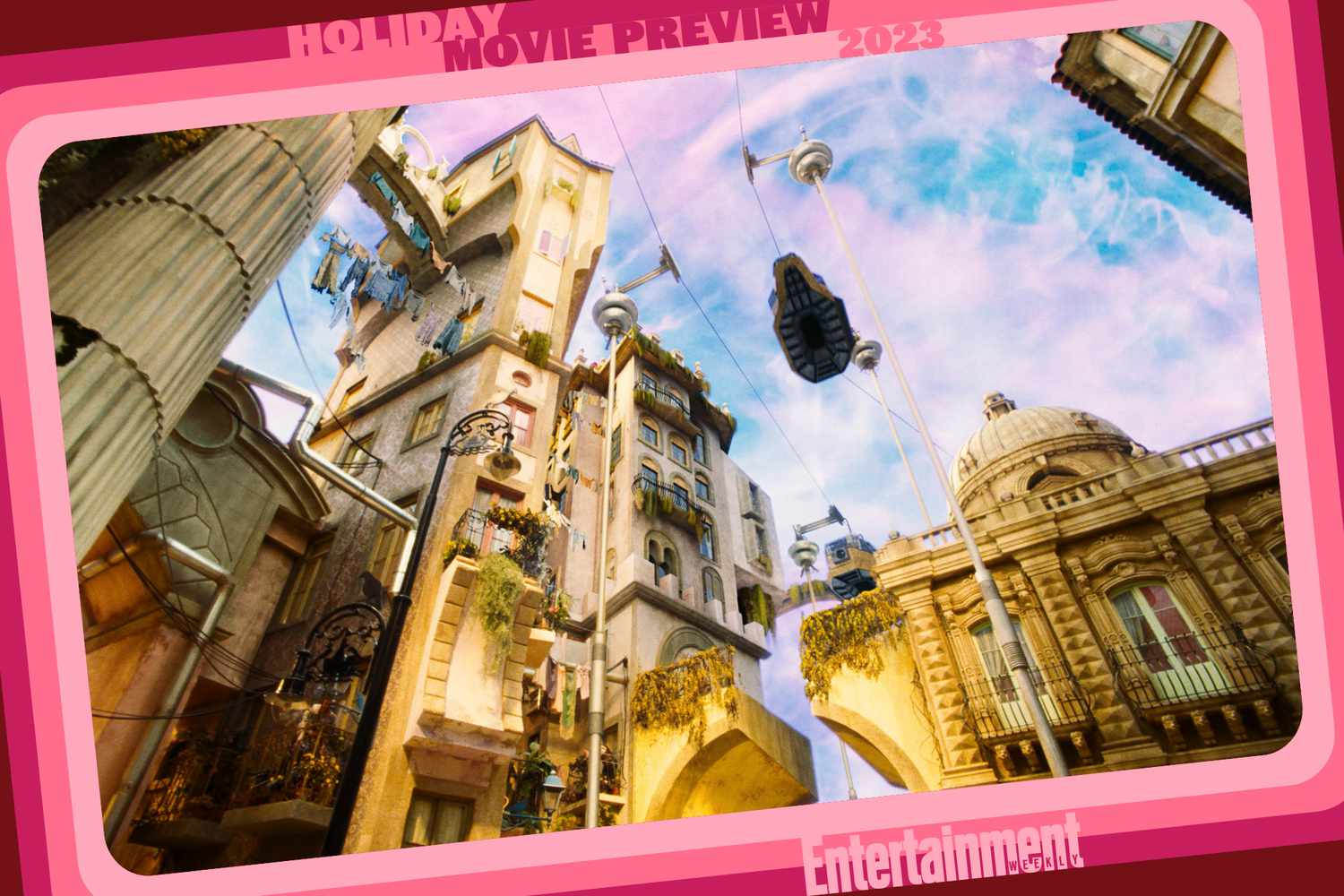

After Bella leaves Baxter’s laboratory, the first place she goes is Lisbon. Instead of shooting on location in Portugal, Lanthimos’ production built a fantastical dream version of the European city entirely on sets, much like a film from Hollywood’s golden age might.

Remarks production designer James Price: “We’ve got to condense the best bits into what is essentially a theme park-size set.”

They also made an important subtraction. In real life, Lisbon is known for its proliferation of blue tiles that resonate beautifully with the nearby ocean. Poor Things entirely subtracted the color blue from its version of Lisbon, making the city feel at once familiar and uncanny. The rest of the film follows a similar visual approach.

Atsushi Nishijima/Searchlight Pictures

A not-quite mad scientist’s lair

Despite the vibrant colors of the outside world, Poor Things begins in black and white, reflecting Bella’s initial infantile perspective. The stylistic choice came as a surprise to Price and fellow production designer Shona Heath, who built Baxter’s house and laboratory as if it were meant to be seen in full color.

“That was a conscious decision that Yorgos made quite late in the prep stage,” cinematographer Robbie Ryan recalls of the 30-minute black-and-white opening. “The production design team was like, ‘What?!’ There’s a beautiful mint green bedroom that really looked gorgeous, and everybody’s a bit sad that it never made it to the final film in color.”

But this is how it worked on Poor Things. Lanthimos set his artistic vision and then empowered his team of creatives — including past collaborators like Ryan and hair/makeup designer Nadia Stacey — to test out different ideas until the director had what he wanted. Even if the final decisions weren’t what team members expected, the final decisions made sense in the context of the film.

“Yorgos turned it on its head,” says Heath, who remembers that the original plan was to also shoot the final scenes in black and white. “But actually, in the end, the detail was there. Yorgos had always been very clear that he wanted deep, maximum texture and really extreme details. So, I think he might’ve had an idea that he wanted more black and white than we thought, but we didn’t know.”

Yorgos Lanthimos/Searchlight Pictures

Monster movie classics

Casting the opening scenes in black and white also makes Poor Things resonate with classic Universal horror films like Frankenstein, which feels like an obvious reference point. Dafoe’s Baxter looks like the titular scientist and Boris Karloff’s monster combined into one being. But James Whale’s masterpieces are harder to imitate than they look; Ryan recalls trying to replicate the crackling energy effect from Bride of Frankenstein, only to be told that contemporary lighting crews aren’t allowed to channel that much voltage these days. In fact, it was a more modern monster movie that provided a model for Poor Things.

“The one we referenced more often than not was Bram Stoker’s Dracula,” Ryan says. “Yorgos leaned toward that one because they used a lot of physical effects and in-camera effects: Miniatures, forced perspectives, and process projections. It has the same kind of wild abandon that Poor Things has.”

Of all the setpieces in Poor Things, none so closely resembles the arsenal of techniques used on Francis Ford Coppola’s practical vampire movie as the cruise ship that takes Bella (under the watchful eye of her lover, Mark Ruffalo’s Duncan Wedderburn) from Lisbon to Paris. The ship itself was a 10-foot miniature, around which Price and Heath used LED screens to create colorful skies and real smoke. The deck and room sets were built with optical illusions and visual details included to make them seem larger than they really were.

“It became an assembly line,” Price says. “We worked out how to rationalize every component and make them in a factory-like setting that could be pre-painted and then just stuck on the walls. There was a great painting towards the bar which gives a false perspective. It looks good on camera, like the boat carries on through those doors, but it doesn’t.”

The ship’s decor is also meant to feel “silly and a bit pompous,” according to Heath. “It was ridiculous that Duncan had put Bella in a box and forced her onto the ship. So, there were a lot of references to caged animals. All the paintings were animals attacking each other.”

Atsushi Nishijima/Searchlight Pictures

Dressing the part

Much of Bella’s struggle throughout Poor Things is to escape the societal norms that confined so many women during the Victorian era, and that energy comes through in her costumes. Despite the elaborate, beautiful nature of the clothing, her looks are often hilariously incomplete.

“Once she goes to Lisbon, there’s this idea that she no longer has any guardian, she’s on her own,” costume designer Holly Waddington says. “So, she’s often wearing things that really wouldn’t go together. She steps out into the Lisbon streets just wearing a pair of knickers, but then the top part of her costume is all intact. It was quite playful and hopefully funny.”

Victorian era fashion was a complicated enterprise, especially for women. There were various types of clothing that were designed never to be seen at all beneath multiple layers of shapewear. Bella, as a newly formed being, hasn’t had those protocols drilled into her head for years. In any case, Waddington says, “She wouldn’t understand the logic of it, it would seem pointless.”

The same is true of makeup. Lanthimos already tries to minimize the use of makeup in his movies; his previous film, The Favourite, used hardly any on its trio of Oscar-nominated female leads. That was a perfect fit for Bella.

“Yorgos wants to see skin and potential imperfections, he wants to actually see the person,” Stacey says. “That’s actually really exciting as a hair and makeup designer to strip back like that.”

Yorgos Lanthimos/Searchlight Pictures

Locks of love

Stacey did get to let loose on Bella’s hair, which also defied Victorian convention with its length. The growth of the long dark hair (itself a major visual change for the usually blonde or redheaded Stone) charts Bella’s growth throughout Poor Things.

“I kept changing the length of it all the way through, until we get to Paris when it’s almost floor-length,” Stacey says. “It’s a real marker of who Bella is, because she’s not shackled to societal norms. At that time, women wouldn’t have had their hair loose and down like that. It just would not have been proper to do that.”

But just like with all good things, even Poor Things had to come to an end. Stacey vividly remembers how it felt when there was no more work to do on the film. “I absolutely fell in love with Bella,” Stacey says. “On the very last day, we cut Emma’s hair. When all the hair that dropped to the floor, we cried because it felt like Bella was gone. But I’m just proud of all of it because every single character, no matter how much screen time they have, has had a huge amount of thought put behind them. Everything had to be, ‘Why are they here? What do they look like? What’s the backstory?’”

See all that world-building thought and visual detail on screen when Poor Things hits theaters on Dec. 8.

Want more movie news? Sign up for Entertainment Weekly‘s free newsletter to get the latest trailers, celebrity interviews, film reviews, and more.

Related content:

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.