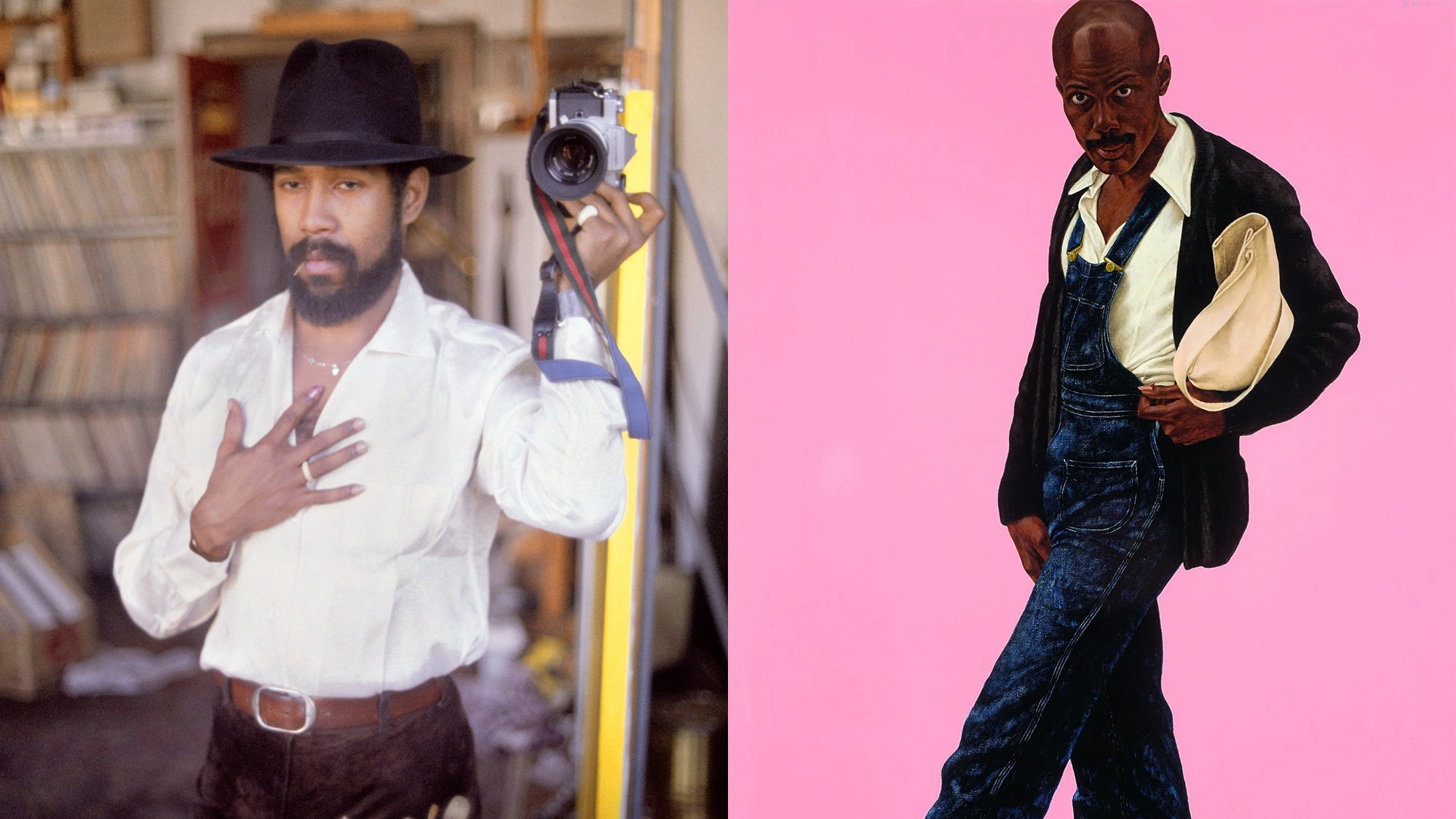

When the writer and Gagosian director Antwaun Sargent was speaking to Aimee Ng, a curator at the Frick Collection in New York, about how best to use the Frick’s temporary home at the Marcel Breur building, it wasn’t long before the pair was discussing the painter Barkley L. Hendricks. And in fact: Hendricks had paid formative visits to the Frick throughout his lifetime, and that collection of Old Master paintings proved to be an immeasurable resource for the artist. Hendricks, who died in 2017, strived to create a sense of power and self-regard for his Black subjects similar to what he found in centuries-old pictures of lords and ladies in the Frick’s Manhattan mansion. There is a poignant courtly sensibility to many of Hendricks’s portraits, which he created during the height of the Black Power movement. His subjects are dynamite kings and queens: an emerald-green fur-lined trench coat glistens and shines like the robe royale, men in loose-fitted two-piece suits exude noble cool, women wear afros like crowns.

Sargent and Ng thought hanging some work by Hendricks near some old European art would be interesting, the Frick agreed, and now Barkley L. Hendricks: Portraits at the Frick is on view until January 7, 2024. The show collects 14 paintings, completed during the late sixties and seventies, that highlight how Hendricks incorporated the techniques and approaches of the Old Masters in his work. For Sargent, who is known for celebrating under-appreciated facets and complexities of Black art, the exhibition broadens the context of Hendricks’ work and places him in direct conversation with the very same European masters he admired. “It really allows you to draw connections between the past and the present,” he said ahead of the show’s opening.“What I hope visitors get is a sense of the sweep of history,” he said. “That you see the Barkley Hendricks work in relation to the masters and contemplate on what beauty means then and what it means now.”

Sargent spoke to GQ about the under-appreciated facets of Barkley Hendricks and his work, the some of the overlaps between fashion and art, and realizing Hendricks worked like a stylist.

Antwaun Sargent: It really allows you to draw connections between the past and the present. You can think about costuming. You can think about jewelry design. You can think about old master painting techniques and the relationship and conversation that continues in the present moment. These are not just paintings that were painted centuries ago. They continue to inform us.

I think when Barkley Hendricks was a youth, traveling around Europe and visiting the Louvre and other institutions, it really ignited in him a deep understanding, but also an engagement, in making sure we were having a full conversation. A conversation that included folks who looked like him and lived in his neighborhood. His family, his friends, fly people who were walking down the street all dressed up. For so long, these images were often of people in power—kings and queens. In painting ordinary folks on the street, Hendricks was saying: these people! He knew they had power. too. They had beauty, and a sense of self, and self-possession that we should take a moment to consider.

We explore his most prolific period of portraiture. Which, really, was the late Sixties through the late Seventies. This was a time he mostly focused on making portraits. After that, through the Eighties and the early Two Thousands, he really shifted more of his focus to landscape paintings, drawing, photography, and other things. We really wanted to show Hendricks at his most engaged with the genre of portrait painting. So we focused on the Seventies, and what all that means in terms of style, the Black Power movement, the post-Civil Rights era, and Black people redefining themselves. And one of the ways that people redefine themselves is through the things that they wear. Barkley Hendricks captured that redefinition as it was happening.

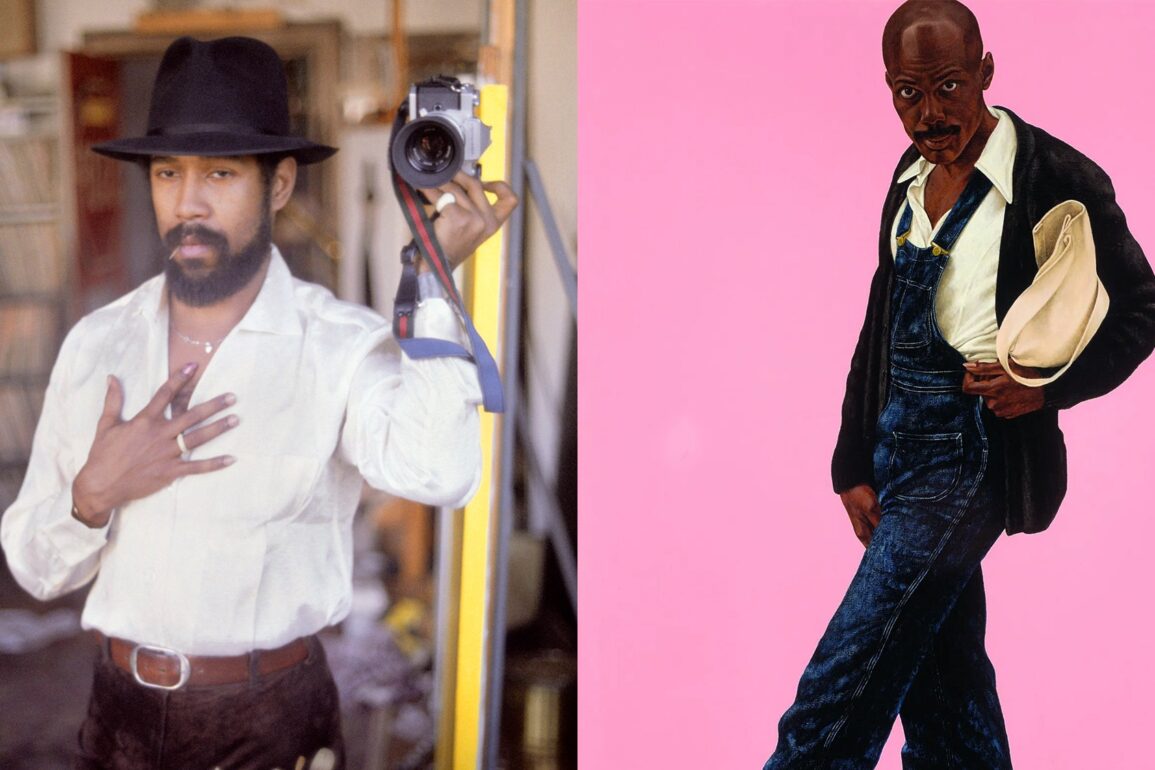

Hendricks, in a way, worked like the street style vloggers of today. He photographed all of his sittings, which were of all the people he painted. He would photograph them out on the street. We included some of those photos in the exhibition’s book and you can see how the subjects are really going for it and striking poses. But Hendricks didn’t simply capture his subjects.

He also styled them, later, during the painting process. There is one work: In the original photograph, the subject is wearing a yellow and blue leotard. But in the painting, he edits the blue out and makes it all yellow. He also removes a necklace—the subject had one. He’s making choices that a stylist would make.

What I love about what Hendricks does—in terms of style— is that he’s showing the power of fashion. To give people a sense of someone’s identity in a public space. When someone gets up and puts something on in the morning—puts clothes on to face the world—you have to take note of that. Because it’s a statement of who they are. I think because these paintings are life-sized, and they hang low, and you are made to see these portraits as people. They’re showing you who they are without saying anything.

When someone looks good on a screen or looks good on the street, it really does set them apart. You sort of have to take notice in a way. It shows a level of individuality that you don’t often see. I think he was really after trying to capture the individual. It wasn’t about making queer people and Black people and women into these political statements, which we as society love to do. But instead he was trying to access their humanity and make sure it was seen on the canvas.

There’s this portrait of this guy in a wide-brim hat—I can’t remember the name of the work right now!—but I used to exclusively wear wide-brim hats and I think it was because of that portrait. Honestly, that’s one of the first things that drew me to his work: the style of it all. I’m someone who grew up on magazines and style culture, and then when I saw Barkeley Hendricks’s work, I was like, “It just looks so good.” I was interested in having some of that self-regard in my own personal style.

I think what it shows, more than anything, is that there is a Black art history that Black people engage in—and a conversation that we have amongst ourselves that connects us. With Barkely Hendricks and his work, you get a sense of music, you get a sense of style, you get a sense of community, you get all of these different aspects of Blackness. I think Kehinde and Jordan Casteel and Amy Sherald, they are all also capturing their ideas of those things. So style might occur differently and might be on display differently in a Mickalene Thomas image than in a Kehinde Wiley one—who is after a very different type of fashioning of Black people. There are all these different constructions of who we are that are sometimes glided over. But they are significant because they show the vast diversity within Blackness and within how we think about ourselves.

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.