Boston is not a town that calls to mind fashion, but a century or two ago, it was the epicenter of the textile industry. Mills across New England wove fine cotton and wool cloth and later crafted finished goods from topcoats to shoes. By the time John Singer Sargent arrived in the city in 1887 for the first of several career-changing visits, an elite class of Bostonians — many of them enriched by the surrounding mills — knew how to dress and did so exceptionally well.

“Fashioned by Sargent,” a new exhibit opening Oct. 8 at Boston’s Museum of Fine Arts, is the first major show to delve into Sargent’s fashion, reuniting dozens of the portraits with garments and accessories worn by their subjects. A stunning cotton, silk and lace beetle-wing sheath from “Ellen Terry as Lady Macbeth” is featured, along with the sumptuous red silk velvet gown worn by Louise Pomeroy Inches in one of Sargent’s earliest Boston commissions.

Inches, a young socialite, married a much older, Harvard-educated doctor known for providing free medical care to people who couldn’t afford to pay. She was pregnant with her third child during her Sargent sitting. Detachable panels allowed the crimson gown to expand with her body, a clever adaptation by a Boston tailor, who copied French couturier Worth’s design.

Sargent chose to emphasize his subject’s arresting face and long, graceful neck, simplifying the gown to avoid distractions by removing adornments on just one of the sleeves.

While his predecessors Anthony van Dyck, Diego Velázquez and Sir Joshua Reynolds often painted their subjects in classical attire, favoring timelessness over the trends of contemporary fashion, Sargent dared to include of-the-moment sartorial flourishes in his work.

“What I love about Sargent is the luxuriousness of his paint,” says Erica Hirshler, the MFA’s Croll senior curator of American paintings, who conceived the exhibit with Pamela Parmal, the now-retired former MFA chair and David and Roberta Logie curator of textile and fashion arts. “From the beginning of his career, he combines — in a really brilliant way— the traditions of the past with modern moments. He’s always walking that tightrope between looking back and looking forward. These are not copies of Old Master paintings, but they’re not necessarily the most artistically avant garde either.”

“Ellen Terry as Lady Macbeth,” John Singer Sargent, 1889, oil on canvas.

Tate Photography/Courtesy Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

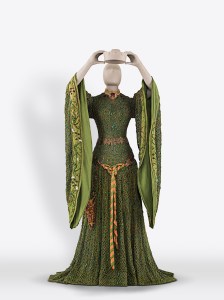

“‘Beetle Wing Dress’ for Lady Macbeth,” Alice Laura Comyns‑Carr (British, 1850-1927), 1888, cotton, silk, lace, beetle‑wing cases, glass, metal.

National Trust Images/David Brun/Courtesy Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

Sargent himself loved clothes and was known for a fastidious approach to getting dressed.

“When we think of self-fashioning and portraiture, we usually think of the sitter, but in actuality the self-fashioning of the artist was just as important at the time,” Christina Michelon, associate curator of special collections at the Boston Athenaeum, says. “Sargent, like other cosmopolitan artists at the turn of the century, cultivated an aesthete or ‘dandy’ persona as bold as his brushwork.”

His sense of style — and skill in capturing it in others — eventually generated more commissions than he could possibly paint, a surprising development given that, by the time he retired from portraiture in 1907, he was charging his subjects $4,000 a sitting, or the equivalent of about $130,000 today.

“Sargent has often been, maybe, criticized as an artist who was beholden to his extremely wealthy, important sitters,” Hirshler says. “What I began to learn was how often he’s actually in control of the portrait.”

Sometimes every gown brought to a sitting was rejected and Sargent chose instead to paint the client in what she wore off the street.

“He often depicted clothes differently than what they actually looked like, making them appear asymmetrical, for example,” Hirshler adds. “And he abbreviated things — or just made them up.”

Hirshler points to his 1904 “Portrait of Lady Helen Vincent,” on loan to the MFA from the Birmingham Museum of Art in Alabama. “He started to paint her in white and changed his mind halfway through, scraping it down. It isn’t clear that she changed her clothes. He just gave her a black dress.”

Adjustments were subtle but often added to the complexity of the portraits, bucking convention or imbuing the sitters with deeper intrigue, intelligence, or emotion.

“The more we study Sargent’s portraits of friends and of enigmatic or strong women, the more dynamic and progressive they seem in that historical moment,” Michelon says. “Class, race, gender and sexuality are all intrinsic aspects of Sargent’s portraits and as scholarly and curatorial methods evolve, so do our interpretations of the work.”

The MFA’s Hirshler began focusing on the fashion in Sargent’s paintings when she was invited to give a paper at the Petit Palais in Paris in 2016. “They had an exhibition about Oscar Wilde, with a symposium about the dandy as a type,” she says. “I presented my paper about Sargent’s portraits of men and then began to think about the clothes in his work and what they said publicly. I proposed this exhibition in 2017 and have been working on it ever since, with some delays during COVID[-19].”

Perhaps because of Sargent’s relative fame during his career, Hirshler found that many of the clothes worn in his paintings still survive, in some form or another — from full ensembles to scraps of fabric clipped from discarded dresses.

“Mrs. Charles E. Inches (Louise Pomeroy),” John Singer Sargent, 1887, oil on canvas.

Courtesy of © Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

“A critic wrote that one of his portraits would become an heirloom,” Hirshler says, prompting many families to retain the sitter’s clothes or else bequeath them to institutions where they could be properly preserved. “There’s great sentimental attachment to these garments. At the same time, the clothes were very expensive and they would go in and out of style. Some were reworked, to maybe fit someone else in the family. You can really sense the sentimentality, holding onto a piece like it’s a wedding gown.”

“Fashioned by Sargent” stays in Boston until Jan. 15 and then travels to the Tate Britain in London.

As museums around the globe pivot toward fashion — jolting attendance, diversifying audiences, and attracting wealthy young patrons in order to stay relevant and solvent — the MFA possesses a rich and extensive archive to mine. The institution began collecting textiles as early as 1871, creating a Textile Study Room for artists and designers back when New England still dominated the American textile industry.

In 1930, the MFA established the first curatorial department devoted to textile arts at any American museum — a full decade and a half before New York City’s Metropolitan Museum of Art created its famed Costume Institute.

From its onset, the MFA’s textile collection has been global in scale, with 16th-century Italian needlework, Turkish velvets, and Indian carpets collected alongside early American embroidery and samplers.

Two years ago, the museum hired Theo Tyson as the Penny Vinik curator of fashion arts to develop and diversify its holdings of 20th- and 21st-century fashion. So far, Tyson has acquired a series of works by Ghanaian-American designer Mimi Plange and curated “Something Old, Something New,” a probing look at traditional wedding attire on view at the MFA through the end of this month.

In March, Tyson and MFA jewelry curator Emily Stoehrer will install “Dress Up,” an exhibit examining how fashion and jewelry shape identity — an apt arrival on the Emerald Necklace, the city’s chain of parks.