Air Date: Week of June 14, 2024

Madam C.J. Walker is considered the first female self-made millionaire in the United States, due to her well-documented wealth she earned from her cosmetics and haircare products. (Photo: Scurlock Studios, Smithsonian Institution, Public Domain)

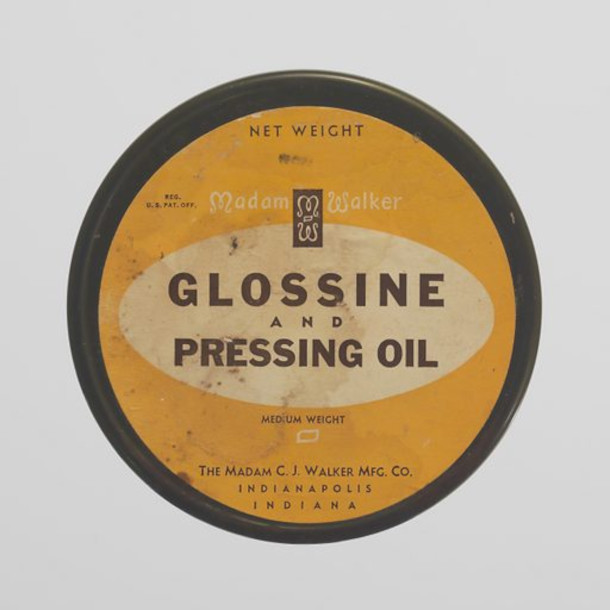

Hair care products marketed to Black women today often include cancer-causing formaldehyde and hormone disrupting chemicals. But back in the early 1900s, an enterprising Black woman named Madam C. J. Walker used mostly natural ingredients in her hair products to empower Black women and become the first female American self-made millionaire. Host Steve Curwood talks with her great-great granddaughter, A’Lelia Bundles, who wrote the 2001 book On Her Own Ground: The Life and Times of Madam C. J. Walker.

Transcript

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood.

Whether you rock a full Afro, a sleek bob or an undercut, the way you style your hair can help you feel confident and express your identity and culture. And it can be complicated for Black people whose hair tends to grow in tight curls. Centuries of racism have contributed to a Euro-centric beauty standard that elevates straight over coiled hair.

JAMES-TODD: As my daughter often would say, when she was little, we have out-hair, like, the way that our hair is a crown, it grows out of our heads, but really, that becoming not the desirable way to operate in society, and down-hair being valued and out-hair being not valued, kind of the three-year-old terms of “out” and “down.”

CURWOOD: That’s Tamarra James-Todd, an epidemiologist at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health. Her research focuses on some of the hair care products Black women use to respond to the social pressures to straighten their hair, risking their health with exposure to hormone-disrupting chemicals.

JAMES-TODD: As a Black woman, like many others, we’ll go to beauty supply stores or to our local pharmacy and get our products. And we are often looking for things that say something like, “will make our hair grow,” or “will make our hair fuller” or whatever, like whatever thing or attribute we equate with being beautiful that we also equate with “this works,” whatever “works” means for us. But what struck me was also that the ingredients saying that they were hormonally active, and I was working in a lab, a breast cancer lab, where hormonal activity was linked to breast cancer. I kind of had this aha moment where I said, is there something to this?

CURWOOD: Cancer-causing formaldehyde is also an ingredient in some hair relaxers and straighteners used primarily by Black women. Amid the growing concerns about health impacts, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration is giving its regulations a makeover. The FDA has signaled plans to ban formaldehyde-related chemicals from some hair products as part of efforts to modernize cosmetic regulations. There are at least ten thousand different ingredients used in cosmetics on the market today, but it wasn’t always like this. In the early 1900s, an enterprising Black woman used just a few ingredients in her hair products to make a huge impact and created jobs and uplifted political engagement. Her name was Madam C. J. Walker, and she made a fortune selling her hair products, making her the first American woman, Black or white, to become a self-made millionaire. Joining me now is the great-great-granddaughter of Madam C.J. Walker, A’Lelia Bundles, the author of the 2001 book On Her Own Ground: The Life and Times of Madam C. J. Walker. Hi A’Lelia and welcome to the show.

A’Lelia Bundles is the author of On Her Own Ground: The Life and Times of Madam C. J. Walker, now published as Self Made. (Photo: CSUF Photos, Flickr, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

WALKER: Delighted to be with you!

CURWOOD: So who was Madam C. J. Walker and what does she mean, writ large, to Black hair care?

WALKER: Madam C. J. Walker was an amazing American business story. Born Sarah Breedlove, the first child in her family born free in Delta, Louisiana in 1867. But by the time she died in 1919, at age 51, she had founded the Madam C. J. Walker manufacturing company, become a millionaire, employed thousands of Black women, empowered them to become economically independent, and used her wealth and influence as a patron of the arts and a political activist. But she really is one of the godmothers of the modern haircare industry, along with other giants of hair care among Black women, but she really created a company that has some enduring legacy.

CURWOOD: When did you become aware of your family’s haircare history?

WALKER: So I would say, and not so much the haircare part, but when I became aware of Madam C. J. Walker and her daughter, A’Lelia Walker, who was a key part of the Harlem Renaissance, was really before I could read, when my mother and I would visit my grandfather in the apartment that, where my grandmother had lived before her death, seven years before my birth, but we would go to that apartment. And while my mother and her father talked in the living room, I would go into my grandmother’s bedroom and open the dresser drawers, and I found things that had belonged to Madam Walker, A’Lelia Walker and my grandmother May. So, ostrich feather fans, and mother-of-pearl opera glasses and souvenirs from Egypt. So I was beginning to learn something about them even as a toddler. The silverware that we used every day had Madam Walker’s monogram, and our china for special occasions had been at Madam Walker’s mansion, Villa Lewaro, in Irvington, New York. So I had touchstones with these women. I, my mom was Vice President of the Madam C. J. Walker manufacturing company when I was growing up. So I would go with her to her office in downtown Indianapolis, go upstairs on the fourth floor and play on her typewriter and her adding machine, before computers and calculators [LAUGHS] and then walk to the factory when she would talk with the ladies who were still mixing the Walker products by hand. So that’s in the 1950s and early 1960s. So I had a sense of my mother being a business woman and this being her family.

CURWOOD: So, tell me, what were the main ingredients of your great-great-grandmother’s haircare formula?

WALKER: You know, it’s something very simple, but that we take things for granted now. And to just kind of set the stage, when she started her company in 1906, most Americans didn’t have indoor plumbing or electricity. So hygiene was very different. And like many other women, she was losing her hair not just because of really serious dandruff, but because of serious scalp infections. And so the formula for the Walker method was a vegetable shampoo that was less harsh than some of the lye shampoos and soaps. Wash your hair more often, get your scalp clean, and then apply an ointment that was a petrolatum base like Vaseline, that included sulfur, which is a centuries-old remedy for healing skin and scalp infections. Products like Cuticura were actually already on the market. There were other products that used this basic formula, medicinal formula, pharmaceutical formula, but she marketed it and packaged it under her own name.

CURWOOD: Now in recent years, and in the news right now, the conversation is loud about the danger of hair chemicals and Black women’s health. What’s your reaction to the FDA’s recent announcement that agency is stepping in to regulate now the chemicals that women use in their hair?

Madam C. J. Walker’s products were often similar to those already being sold, but her understanding of marketing allowed her business to thrive. (Photo: Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture, public domain)

WALKER: I’m glad that this attention is being paid to the harm that chemicals can do. You know, what Madam Walker and her contemporaries developed with petrolatums and petroleum-based and sulfur-based products, you know, now we know that with shampoos, they’re sulfate free, that we don’t use petroleum based. But during that period of time, that was revolutionary. And sulfur was somewhat harmful, but not in the way that the chemical straighteners that came a couple of generations later, that this hydroxy is, I think, can be very harmful. And I think some of the scientific studies show that.

CURWOOD: So, tell me as a Black woman, as a writer, journalist, historian, talk to us about the emotional and psychological ties between Black women’s sense of self and their hair in modern America.

WALKER: So much of this is how we see ourselves, what our self-image [is], how we present ourselves to the world. And a lot of the way that we feel about ourselves depends on the messages that come from the people who are closest to us. Though sometimes, I do have friends who wear their hair natural, whose daughters really want to wear lace front wigs, or they really want to straighten their hair, they don’t want to do what mama did! But we, I think there is a journey, at least for myself, personally, that many of us go through in terms of becoming comfortable with who we are. And that’s not to say that, you know, some people, especially I think young women and teenagers, want to change their hair every other week. And I think they ought to have the freedom to do that. But I personally, like to be able to wear my hair without any extra, without any extra things, without extensions. That’s just me. But I kind of admire the creativity of some of the young women. But I do think it really does have to do with the messages that we get. A couple of examples for me: so when I was growing up, I had very long hair and I was what we would say “tender headed”. And my mother was very patient with me, she took a lot of time. And when I would, you know, squirm, she would say, “Oh, you know, sweetie, you’re gonna be so pretty when we finish.” And that was her way of trying to give me confidence. She bought Black dolls for me. So there was a message there. That did not prevent me from feeling the pressure of the external world. I always went to predominantly white schools. So you begin to compare your hair texture to the hair texture of your classmates. And because of this emphasis on European standards of beauty, I think that many young girls and, you know, women and older women feel this pressure to conform. But if you have a family member or someone close to you, or a boyfriend or a girlfriend, who says, “I would rather your hair be this way than that way,” sometimes it’s very hard to assert yourself and say, “But you know, this is my hair, this is the way I want to wear it.”

CURWOOD: Now, what about the business marketplace? I’ve heard some Black women say that, if they wear natural hair in the corporate setting, it really sets them back. They don’t advance as far and they feel that they have the evidence that straightened hair gets them further than natural hair. What do you think about that?

WALKER: I think that’s absolutely true. But you know, my personal experience as a producer and an executive with ABC News, and then having worked with NBC and ABC for 30 years, I watched an evolution of hair. I started at NBC in 1976. And one of the reasons that I chose not to take the on-air route is because I had a big Afro and I did not want somebody telling me how to wear my hair. But behind the scenes, I could wear my hair however I wanted without that kind of pressure. Then through the years as I had different jobs, my last position was as Director of Talent Development at ABC. And so I was working with young correspondents, people who were just coming on board, hiring new employees. And I know that it was very difficult, that people were sort of dismissed if they didn’t have straightened hair. But I’ve noticed within the last sort of decade or so, especially on MSNBC, that the women attorneys, who had natural hair, were brought on the show because they brought some expertise. So I’m coming with my brain, and my hair comes with me. I even noticed that a one of the male hosts on CBS Morning News the other morning had cornrows. So people are pushing that envelope; when you see executives like Debbie Lee or Sheila Johnson or B. Smith, when she was in the public eye with natural hair, or Ursula Burns, it begins to change the equation when somebody at the top has the courage to do that. And it’s not even courage, it’s like, this is the way my hair grows. So I think we are in a moment where there are people who think they can still intimidate you. And if you’re in a place where there are not a lot of eyes on you, and there’s not a lot of legal recourse, there are still people who will tell you you cannot wear your hair a certain way. We know that if you’re just starting out or if you’re in a place where you don’t have a lot of power, it’s very hard to fight back.

CURWOOD: So, A’Lelia, what inspired you to write the book On Her Own Ground: The Life and Times of Madam C. J. Walker?

Black women can lower their risk of reproductive cancers by avoiding certain hair straightening products, but natural Black hair is often stigmatized in America. (Photo: Nappy.co, CC0)

WALKER: I was really more interested in A’Lelia Walker than Madam C. J. Walker, because A’Lelia Walker, my great grandmother, Madam Walker’s daughter, had known the artists and writers and musicians of the Harlem Renaissance. And my senior year in high school, I, we convinced the school administration to let us have a Black history humanities course. So I wrote about A’Lelia Walker and her Harlem Renaissance friends, and that was my interest. Madam Walker was really complicated for me, because people thought, oh, Madam Walker, isn’t she the woman who invented the hot comb? Well, she didn’t invent the hot comb, but that was the narrative about her, and I was kind of keeping her at arm’s length. So it took me a while to fully understand her many dimensions. And when I got to Columbia and journalism and graduate school, my advisor for my master’s paper was Phyllis Garland, the only Black woman on the faculty at that moment when those doors were finally opening up for diverse hires. And Phyl and I sat down to talk about my master’s paper topic, and I gave her the kind of cliched, trite topics that students give to their professors. And at the end of the conversation, she said, “Your name is A’Lelia. Do you have any connection to Madam Walker and A’Lelia Walker?” And I’m pretty sure Phyl knew the answer to that question. Her mother had been editor of the Pittsburgh Courier, she had worked for Jet and Ebony. But I wasn’t walking around talking about my relationship to them. So when I said, “Why, yes, that’s my family,” she said, “That’s what you’re going to write about.” So it was really the power of a professor who understood the importance of that story, who validated it for me, and who really set me on a path that’s really kind of five decades old, almost.

CURWOOD: So what was the story you tried to tell in On Her Own Ground?

WALKER: I wanted people to know about Madam Walker’s many dimensions, because she had such good instincts about hiring her executive team that they created, they saved the records. So we have literally 40,000 documents and photographs that were donated to the Indiana Historical Society that have been digitized. So I had incredible, an incredible foundation for my research. And then I spent many years reading other manuscript collections and newspapers and doing research. So after I had done this research, I realized, yes, she had founded a haircare company, that was very important. Yes, she had become a millionaire. But what intrigued me was the jobs that she created for thousands of Black women who otherwise would have been maids and laundresses and sharecroppers; allowed them to become economically independent, to buy homes, to buy real estate, to educate their children, but also empowered them to become leaders in their communities. So that was fascinating to me, that she based it on the things she learned from the women of her church, the St. Paul African Methodist Episcopal Church, from the women in the club movement, that leadership was important. I loved learning that she had been politically active. She was a, she was a political radical [LAUGHS] which just, you know, amazed me and made me feel good that during World War One, she spoke out against lynching, she spoke out on behalf of Black soldiers. She was even spied upon by a Black spy who was working for the War Department and, along with Ida B. Wells, was called a “Negro Subversive,” which is like the Nixon’s enemies list. So I wanted to show those many dimensions and the impact that she continues to have, to inspire entrepreneurs, but also to inspire people to not only become wealthy and influential but to use that wealth and influence in a political way and to support the arts.

CURWOOD: Before you go, A’Lelia, tell me: what is Madam C. J. Walker’s legacy?

WALKER: For me, Madam C. J. Walker’s legacy is one of empowering women and one of inspiring women. She really does show us the possibilities of what can happen both when women have confidence, but also when they have leadership and they can make a difference in their community. One of my favorite things, as I’ve done all this research, is something that Tiffany Gill, a friend of mine who’s a historian, discovered when she was doing her dissertation, and she was looking at women in the Civil Rights Movement, in particular beauticians during the Civil Rights Movement. And what she learned is that beauticians, women who were members of the National Beauty Culturists’ League, that they were very politically active. I think some of those seeds were planted by Madam Walker in that 1970 convention. And those beauticians would invite Martin Luther King to their conference, their convention every year, and they helped pay for the buses that took people to the March on Washington in 1963. It’s significant to know that A. Philip Randolph’s wife, Lucille Green Randolph, was a Walker agent. So I love this mix of women who are economically independent, own their own businesses, being leaders and being able to use that for social justice.

CURWOOD: What else would you like us to know?

WALKER: We can twist ourselves into knots trying to look like somebody else. And I think it is, there’s a lot of reckoning that is important for women to do in terms of how we feel about ourselves. I know that for me, personally, I’ve had a long haircare journey, for 70-plus years. It’s taken me a while to be comfortable with myself and to realize that my hair texture has all my ancestors, as does the person sitting next to me have all her ancestors, and what I can do with my hair is not what you can do with your hair, that it’s so important for us to love ourselves. And that’s, that’s really for me, the most important part of a haircare journey, is what is it that we do that makes us feel good about ourselves and love ourselves?

CURWOOD: A’Lelia Bundles is the great-great granddaughter of Madam C. J. Walker. Thanks so much for taking the time with us today.

WALKER: Totally my pleasure.

A’Lelia Bundles is the great-great-granddaughter of Madam C.J. Walker. (Photo: Courtesy of A’Lelia Bundles)

Links

Learn more about A’Lelia Bundles

Purchase A’Lelia Bundles book and support both Living on Earth and local bookstores

Listen to our previous story on the risks of certain Black haircare products

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.