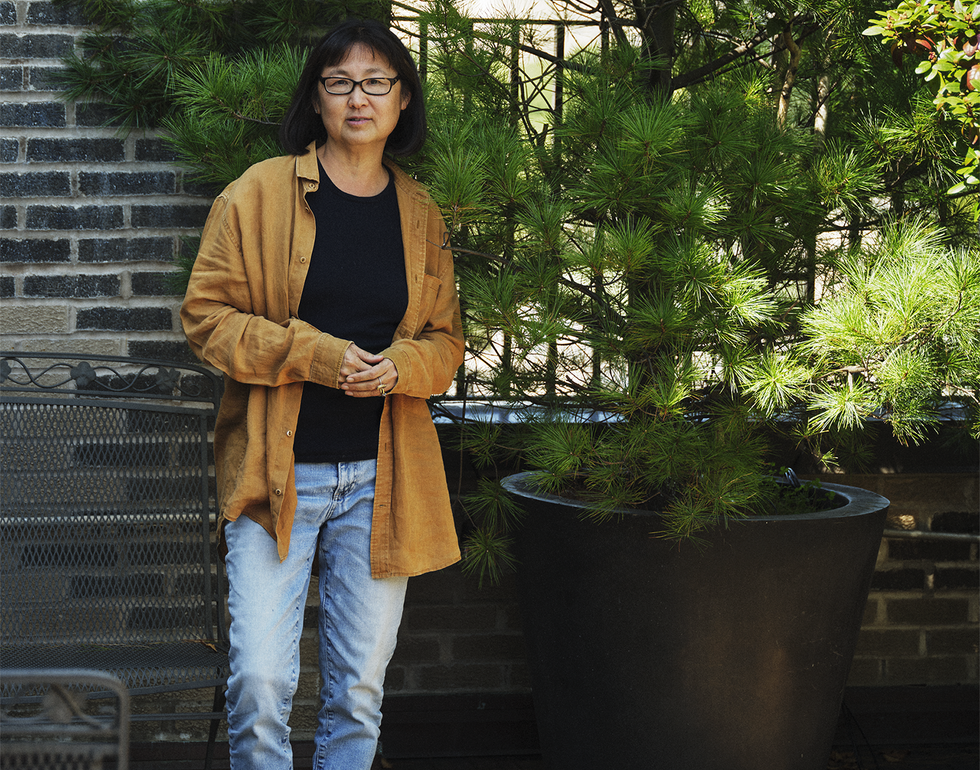

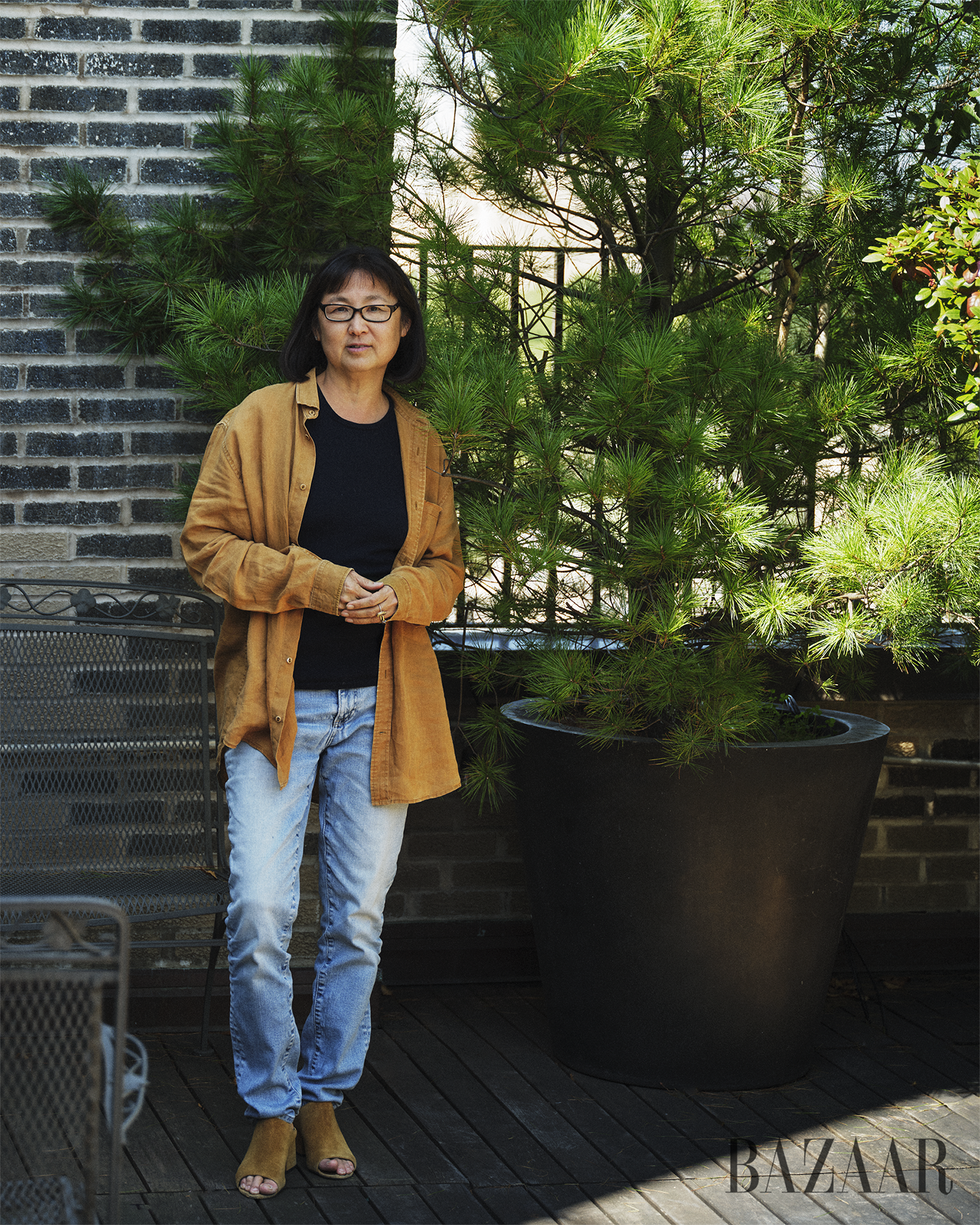

One morning in September, Maya Lin welcomes me into her apartment, a series of merged units with Gothic-style windows near Central Park in New York City. At five foot three, with her signature long bob, Lin, now 64, is slight, with an affable demeanor and a surprisingly low voice. Dressed in jeans and a brown shirt, she ushers me outside to her rooftop terrace, where an array of potted plants lends a lush calm to the frenetic energy of the city below. Lin recently adopted a nine-month-old mini-Aussie puppy named Sable, who circles us before scampering inside.

Lin likes working from her bedroom, which is just down the hall. She always has—ever since she was catapulted to fame in 1981 as a 21-year-old architecture student at Yale, when the design she created in her dorm room was selected from 1,421 submissions for the Vietnam Veterans Memorial in Washington, D.C. There and on airplanes, where she feels slightly out of reach from life’s demands. She has her studio downtown, of course, where she employs a handful of people, and not too long ago she took over the downstairs office of her late husband, the art dealer and collector Daniel Wolf, renowned for the world-class collection of photography he assembled for the J. Paul Getty Museum in Los Angeles. In January of 2021, Wolf died suddenly, at the age of 65, after suffering a heart attack. The family, which includes their two daughters, India and Rachel, had all been together at their house in Ridgway, Colorado, when it happened. The couple had been married for almost 25 years. When the subject comes up, Lin’s face, at first gracious and warm, stiffens briefly into a mask. “It rocked us all,” she says.

Wolf’s death came at what was supposed to be a celebratory moment for Lin, whose memorials, buildings, landscapes, sculptures, and mixed-media and conceptual works have explored our relationships with nature, memory, the environment, and the spaces we create and occupy. First, there was the unveiling in March 2021 of her redesign of the Neilson Library at Smith College in Northampton, Massachusetts, a building constructed in 1909 with a traditional brick facade that was obfuscated by later expansions. (Lin restored it and added a pair of elegant, window-filled extensions on either side.) Then there was her Ghost Forest installation in New York’s Madison Square Park that May, which involved transporting 49 leafless Atlantic-white-cedar trees from a dying grove in the New Jersey Pine Barrens decimated by the effects of climate change and placing them in the public space. A comprehensive exhibition on Lin’s life that opened last year at the National Portrait Gallery in Washington was also in the works—the first the museum had ever devoted to an Asian American person. “It was an insane year,” Lin tells me. “It was the best year and the worst year of my life.”

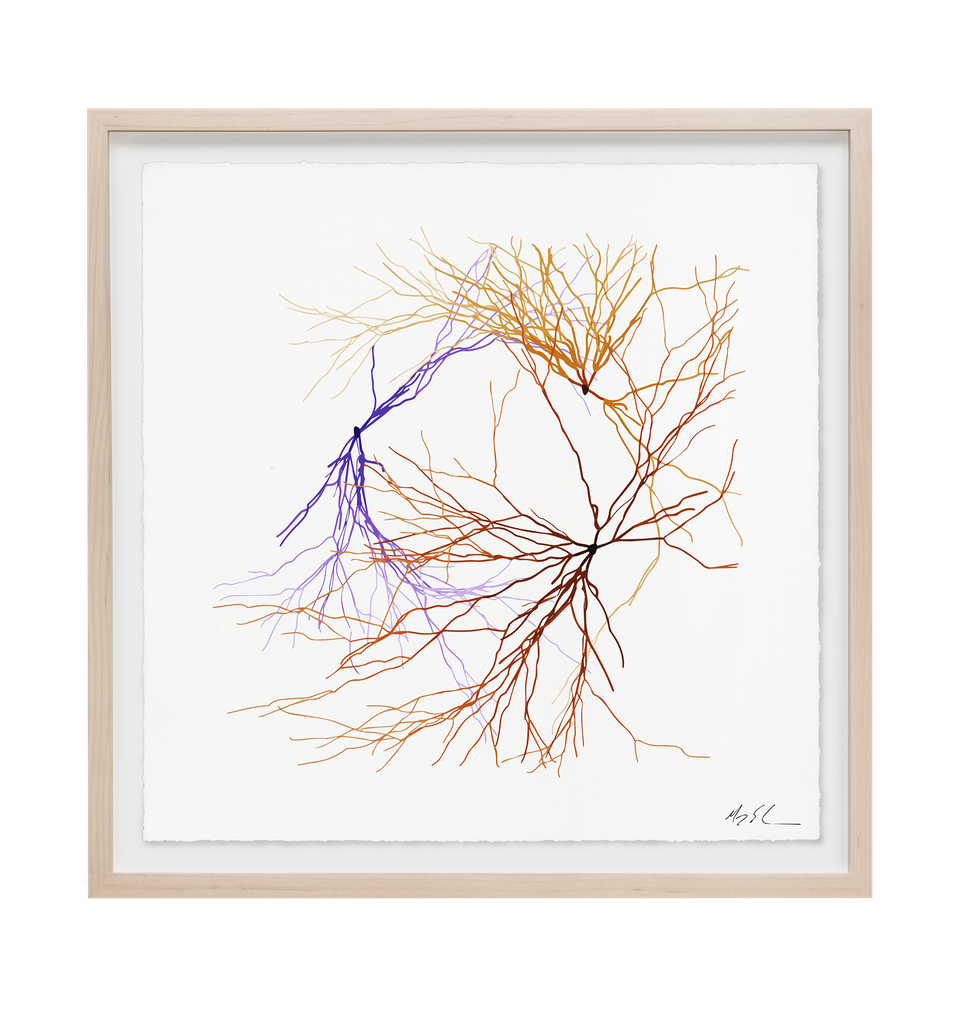

Grief only prompted Lin to throw herself back into her work. Since then, her plans for an ambitious new home for the Museum of Chinese in America in Lower Manhattan have been announced, along with a new performing-arts studio building at Bard College, among a number of other ongoing projects. In October, Lin’s Ghost Forest Seedlings—an extension of the original Ghost Forest—debuted at Pace gallery in New York. The works depict digital “seeds” that will germinate in a distinct root pattern, formed using an algorithm intended to mirror natural growth, and exist as both physical objects and NFTs, her first foray into the realm of generative art.

Last year, it was also revealed that Lin had been commissioned to create a public work for the forthcoming Obama Presidential Center on the South Side of Chicago, which is set to open in 2025. Lin’s sculpture, Seeing Through the Universe, will sit in the center’s Water Garden, honoring former president Barack Obama’s late mother, Ann Dunham. A circular oculus will mist next to a flat pebble-like fountain, where water will cascade down its curves.

“Maya is one of President Obama’s favorite artists,” says Louise Bernard, the director of the Obama Presidential Center Museum. “She taps into that same sense of possibility that we see exemplified by Barack Obama himself. They are both figures who mean so much to so many people, both in the American landscape and globally. The president, I’m sure, feels that connection through Maya’s work.”

Lin has always been an adept planner. But with the loss of her husband and her two daughters now out of college, she’s facing a future that she never quite had an opportunity to imagine, at least so soon. She’s still trying to get her bearings. When I ask her what chapter of her life she is in now, she pauses. “I don’t see life as chapters,” she offers. “It’s one big blur. Dan and I were about to be empty nesters, and then Covid hit, so we got an extra year as a family, which was really nice. It was a great year to be together. Who would’ve thought that it would be our last?” She knows, however, that to recover, what she needs is time. “I’m in a little bit of a limbo right now,” she admits. “I’m adjusting.”

If, like me, you grew up Chinese American in the 1990s, then you probably found Lin to be a pathbreaking figure. When I look back, it’s almost hard to describe the effect she had on me. She was creative, ambitious, and educated, but she wasn’t a doctor or an engineer or the product of a “tiger mom” household. She was supremely intelligent, beautiful, and even a little bit cool. But most importantly, Lin was her own person. Early on, she started wearing rugged work shirts and denim as way to counteract the condescending treatment she received as a 20-something woman of color working in fields often dominated, and gate-kept, by white men. She laughs as she recalls interviewing contractors to help build the Vietnam Veterans Memorial and a group of men from a firm they were meeting with offering her milk and cookies. “I don’t drink dairy,” she says. “But I ate a cookie.”

The controversy that surrounded the memorial, with some veterans objecting to Lin—young, female, Chinese American—as its creator, left her wary of attention. She eventually had to testify in front of a Senate subcommittee to defend her design. Despite, or perhaps because of, that early exposure, Lin has always drawn a strict line around her private life. But she also understands why speaking about her work is important, especially to the nonprofits and institutions with which she often collaborates. “You owe it to the project,” she explains. “So I really hope I’ve been able to say, ‘Here’s my work. It’s public. But I’m not.’ ”

For the most part, Lin has been able to pick and choose the kinds of projects she wants to do. She won’t take on architectural commissions that contribute to urban sprawl, and while her work often requires the enlistment of teams of designers, builders, fabricators, engineers, landscapers, computer scientists, and specialists to bring it to life, she is integrally involved in everything. A couple of years ago, she was traveling with her family and had a hard time getting her fingerprints to read at an airport checkpoint. She believes working so much with Plasticine may have flattened the ridges on her fingertips. She shows me her hands, and I can barely make out the pattern of spirals on her fingers. “If I work on the project, you’ll get me,” she says. “For better or worse.”

Lin spent her childhood surrounded by nature. She was born in 1959 in Athens, Ohio. Her parents, Chinese immigrants, were professors at Ohio University. Her father was the dean of the College of Fine Arts, and her mother taught English and Asian literature. Athens, which is in the foothills of the Appalachians, is filled with tall oak trees, open glades, and running streams that served as a kind of playground for Lin and her older brother, Tan. The family lived in a house at the end of a long, wooded driveway. Lin loved its deep sense of isolation, even if other children found it spooky. “No one ever went trick-or-treating there,” she says.

By the time Lin came of age in the late 1960s and early 1970s, environmentalism was gaining stride in the public consciousness. Advocacy groups such as the Natural Resources Defense Council and Environmental Defense Fund were successfully taking on polluters for the damage they had wrought, and legislation such as the Clean Air Act of 1970, the Clean Water Act, and the Endangered Species Act was being passed. “I remember the Cuyahoga River near Lake Erie caught on fire,” Lin says, referring to the infamous 1969 blaze caused by a spark from a railroad track that ignited debris on the water. The incident indirectly led to the creation of the Environmental Protection Agency and a growing awareness around the negative impact that industry, urbanization, and human activity were having on the environment. “There were news reports about there being too many blackbirds and starlings in Tennessee and Kentucky, so they sprayed them with some horrible chemical. I remember seeing these horrible images of masses of dead birds,” she says. A young Lin was driven to activism. “Something in me shifted,” she explains. “I was literally out in the parking lot of Kroger’s with a petition to boycott Japan to save the whales.”

Nature is one of the strongest influences on Lin’s work. It’s present in the Vietnam Veterans Memorial, which gleams like a geode that has been cut from the earth. Or Eleven Minute Line (2004), which takes its inspiration from the ancient burial and effigy mounds of the Hopewell and Adena tribes near where Lin grew up in southeastern Ohio. As part of The Confluence Project (2006–2015)—comprising several large-scale landscape installations along the Columbia River in Washington State and Oregon —Lin helped persuade officials to reduce the size of the parking lots at Cape Disappointment State Park to allow a restoration of grasslands and wetlands.

“Maya is one of the great visionary artists of our time,” says Brooke Kamin Rapaport, the artistic director and chief curator at the Madison Square Park Conservancy, which commissioned Ghost Forest. “She has guided us to respond to nature and to take action through nature-based solutions for climate change. That’s an ongoing foundation of her practice.”

These days, Lin has evolved into something of a wonk. She frequently cites statistics about food supply, nature-based solutions, and biodiversity. “It would take $1.6 trillion annually to mitigate climate change” by reducing global greenhouse-gas emissions, she offers. “That’s what we spend on alcohol.” It’s in part an outgrowth of her work on What Is Missing?, an ongoing multiplatform installation she started in 2009 dedicated to what has been lost to environmental degradation. On the What Is Missing? website, you can learn about the wild sturgeon of the Hudson River, which were once so bountiful in the late 1800s that they prompted a small gold rush. Or submit a memory of seeing fireflies—many species are now at risk of extinction because of habitat loss and light pollution—in a field on a summer evening.

When Lin was younger, she often came across as a person determined to prove that she was more than just her initial success. Back then, architecture was considered much more separate from art, with the two disciplines rarely in dialogue. She remembers talking to some former classmates from Yale who were in the art world and being told that she wasn’t an artist. This was years after she designed the Vietnam Veterans Memorial. “I realized everyone at the table—because I hung out with mostly artists—could be called an artist,” she says. “But because of what I had done, it would take about 15, 20 years before people could see me as one.”

Adam D. Weinberg, the former director of the Whitney Museum of American Art, says Lin’s multidisciplinary approach is part of what makes her work so compelling. “Her strength is that she doesn’t neatly fit into any category,” he says. “With really great artists, they make up their own worlds. They make up their own stories. They make up their own beings. The world has to catch up with them in a way.” Lisa Phillips, the director of the New Museum in Manhattan, has known Lin for two decades and finds her approach to art-making pioneering. “More and more, we see artists who aren’t working as the isolated sole practitioner but rather are making work that involves collaboration with others in different fields,” Phillips says. “Maya has been doing that all along.”

On a number of occasions, Lin’s work has been labeled “subtle” or “well-mannered.” She doesn’t disagree with me when I suggest that such adjectives are commonly used to stereotype Asians as silent and hardworking—an idea that encompasses, on the one hand, the inescapable myth of the model minority and, on the other, a much older trope of submissiveness and servility. “I find it a little odd,” Lin says, shrugging. “There’s a little subversion going on because I choose to put something out in a really loud, public setting—something that’s going to force you into a different mindset. But that’s not the same as trying to muscle your way in. So, oddly, ‘subtlety’ is not that subtle, right?”

Like so many Americans, I have visited the Vietnam Veterans Memorial. I remember placing my hands on the black granite, feeling the names of the fallen soldiers, and seeing my reflection in its mirrorlike surface. This, we know, was all part of Lin’s design. As Louis Menand wrote in The New Yorker in 2002, the memorial “doesn’t say that death is noble, which is what supporters of the war might like it to say, and it doesn’t say that death is absurd, which is what critics of the war might like it to say. It only says that death is real and that in a war, no matter what else it is about, people die”—which, Menand wrote, is what makes it “one of the great antiwar statements of all time.”

The way we think about monuments—once static, figurative pieces of sculpture—has changed dramatically because of Lin. They are now, more often than not, abstract and site-specific works of interactivity—absence, under Lin’s influence, being just as potent as heft. Consider New York City’s 9/11 Memorial, designed by the Israeli American architect Michael Arad: two elegant waterfall pools surrounded by a grove of swamp white oaks that mark where the Twin Towers once stood.

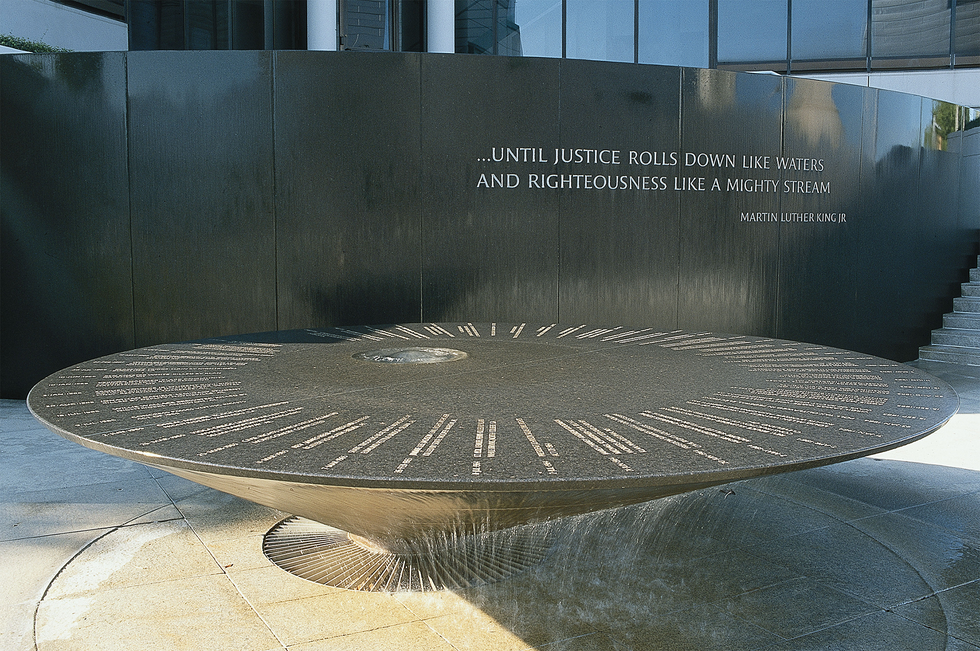

Lin has long outgrown her own reputation as a memorialist, having announced more than 20 years ago in her book Boundaries that her days as a maker of monuments—including 1989’s Civil Rights Memorial at the Southern Poverty Law Center in Montgomery, Alabama, and 1993’s The Women’s Table at Yale—would eventually come to an end. But her art, her architecture, her landscape works—all of it lives beyond its creation. After Ghost Forest was installed, Lin loved watching people sit beneath the trees on their lunch breaks, perhaps even unaware that they were interacting with a work of art. I remember once seeing a couple embrace on one of the grassy hills of Wavefield (2009) at Storm King Art Center in New Windsor, New York. I remember a man mournfully kneeling at the Vietnam Veterans Memorial. Gestures like these don’t belong to Lin, but her work is what has allowed them to happen. Lin is always searching for such moments of revelation. There is a poetry to her empiricism that few other artists have come close to emulating. To her, how we see the world matters.

Our conversation drifts, at one point, to the images of space from the Hubble telescope. “Some scientists chose the colors for those images of the Horsehead Nebula, and they’re beautiful,” she says. “One day we’ll look at those as art.”

A version of this story appears in the November 2023 issue of Harper’s Bazaar.

Hair: Fernando Torrent for R+Co; makeup: Steven Canavan for Dior Forever.

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.

![Maya Lin;Maya Lin [Misc.] architect maya lin l standing on balcony of building where her civil rights monument is being dedicated at the southern poverty law center where civil rights leaders others are convening photo by thomas s englandgetty images](https://hoodoverhollywood.news/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/hbz110123wellmayalin-002-654be08c1b60b.png)