What are your earliest memories growing up in Lagos?

Mowalola: I don’t look at them by year; I look at them by feeling. The things I think about the most growing up are being outside with my brother, Adey.

Tiwalola: Recreating scenes from Mulan.

Mowalola: Oh yeah! We used to put on variety shows for our parents every week, and we would perform.

Tiwalola: We were recreating Destiny’s Child with all the dance moves. Sometimes we created Disney movies. Others, we would just sing – but there was a show on every evening.

Mowalola: From early on, our mum let us play and express ourselves. She even let us pick what we wanted to wear, even though we looked crazy.

Tiwalola: At the beginning of our mum’s career she would go to these bazaars and sell children’s clothes, and my sister and I would model. We were her first models because she started her business making pyjamas for us, and then it grew into the conglomerate [Ruff ’n’ Tumble] that it is today in Nigeria. She had that creative flair in her. Naturally, we started to get confidence and express our own creative flair. That was part of our fun growing up; self-expression was at the core of everything.

Tiwa, what would you say about Mowalola growing up?

Tiwalola: Mowa was creative, she could draw and paint. She would play with her Bratz dolls and come up with all these incredible storylines that were so unique. She could sew and make bags; for her art project when she was 12, she designed a bag and a pair of shoes.

Mowalola: Tiwa is my partner in crime. In Lagos, we didn’t have electricity most times during the day and we couldn’t watch TV during the week, that was a household rule. So we would just spend a lot of time acting. We would play school; we would play church. There was no wacky idea I wanted to do that she would say no to; she was always down to have fun with me and I appreciated that.

You both seem to have developed the same entrepreneurial spirit. Mowa, did you ever want to work for or under anybody else?

Mowalola: Right now I work with Ye. That’s the only person I feel suits the way I create because he lets me do what I want. He is also very supportive of my brand. The way I want to create and perceive fashion is not to be solely about the two cycles, [it’s about] creating more of a community beyond a fashion brand. I feel like maybe that doesn’t align with most people’s directions of how they want brands to be. Also, I mean, I’ve never seen any Black woman at the head of any house, and I keep seeing all these diagrams of the history of fashion houses and it’s all white people. It feels like it’s already decided that it isn’t a space for a Black woman, you know? I feel like they’re only just testing out the Black man now. The Black woman doesn’t even cross their minds. But I enjoyed working with other people. I interned with Wales Bonner; I feel like I learned a lot from her. I also worked with Sophie Buhai, the jewellery company in LA, and I learned a lot from that too.

Tiwalola: I think we’ve grown up with this sense of not waiting for people to give us a chance. You create your opportunities; you give yourself the chance. Our grandma was also an entrepreneur; she was an incredible woman, an absolute trailblazer. She moved to Nigeria in the late 50s or early 60s; she was white-Scottish and she married a Nigerian man and moved to Nigeria on a boat that took two weeks. It’s a pioneering spirit; not everyone is going to get you and not everyone is going to see your greatness, but you have to see the greatness inside yourself. My mum definitely passed that on to us. Seeing my mum working and building her empire is also really inspiring, and that’s why representation is so important, because when you see other women killing it and being baddies, you’re like wow, if they can do it, I can do it too.

Mowalola: We don’t operate from a position of scarcity, we operate from abundance because we’ve seen mum, we’ve seen grandma, and so we want to see more of that.

There is also something about the energy or spirit of Lagos… the hustle.

Mowalola: It’s a very special environment because everything around you tries to deter you from eventually being free or even just creating, because everything is a fight. It’s so special because no matter how many times we get pushed back, we’re still wanting better. I look at the biggest musicians, at great actors and I’m like wow, if we had good support from our country we’d be doing even more than this.

Tiwalola: I’d say our resilience as Nigerians is a blessing and a curse because when you are very resilient, you can overcome a lot of situations, but there are a lot of things our government throws at us that we shouldn’t accept. And because we find a way around it, it becomes acceptable. I think it’s because of all the different hurdles we have to [jump] that we are naturally very resilient people. It pains me and also gives me joy to see everything we’ve been able to achieve despite all the toughness thrown at us. But imagine what Nigeria could be if things worked and if the government supported young people and let them live out their dreams. It’s a bittersweet thing.

One of the great things coming out of this struggle is the alté scene – would you consider yourself a part of that scene?

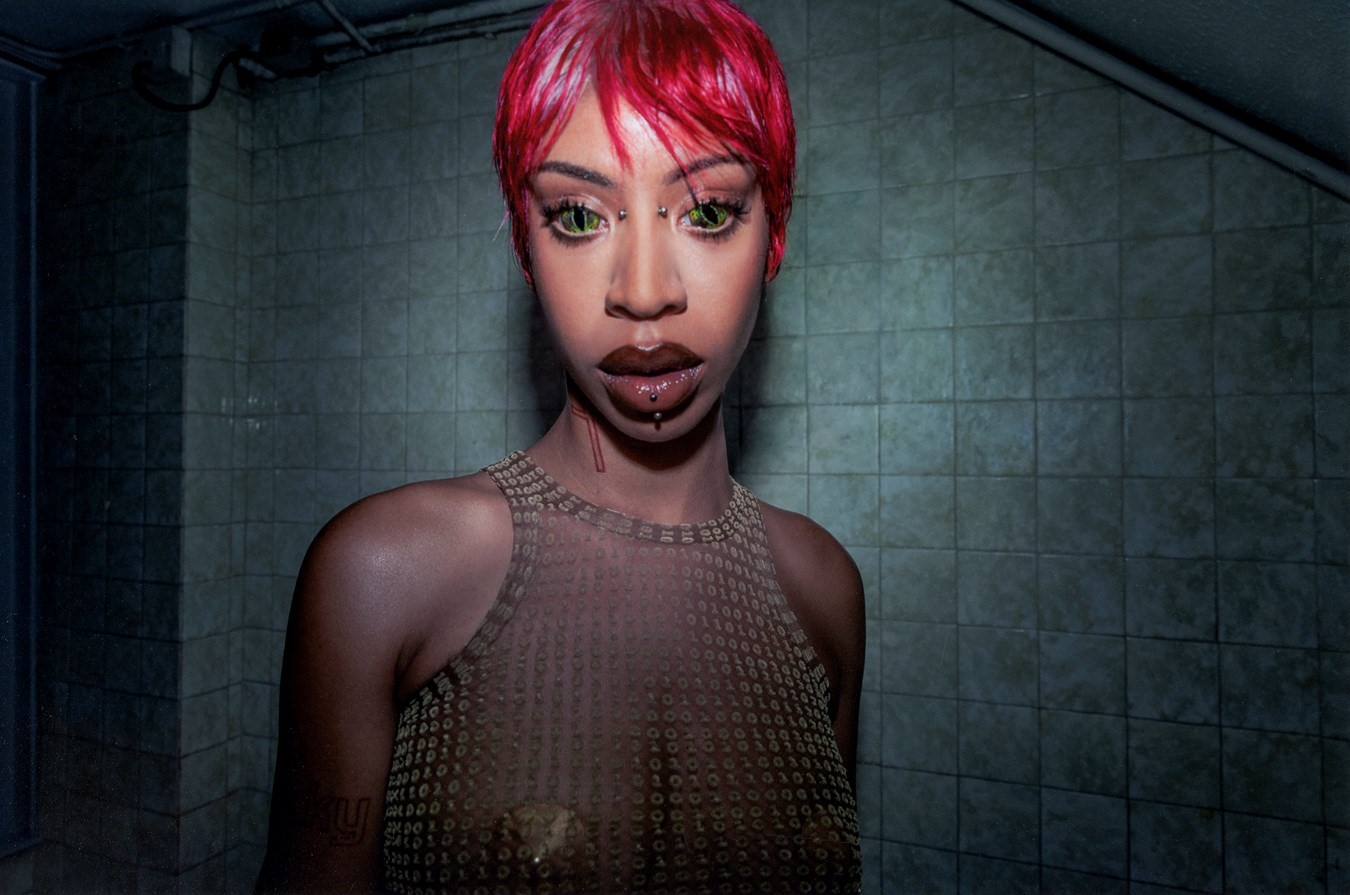

Mowalola: I guess so, I’ve created [work] with the people who pioneered it. I feel like growing up in Lagos was kind of lonely because I just had Deto [Black, musician and childhood friend photographed for this story] who was also a bit different. Before, when you would listen to Kid Cudi, people would say you were ‘alté’ as an insult. It didn’t have the power it does now. When I left [Lagos], Santi and Odunsi [the Engine] created this ecosystem of alternative creatives, and because of the things they were doing it then became a term of endearment. They were no longer looked down on; they were pushing culture.

Tiwalola: I think Ashley Okoli is another person who definitely pioneered as part of the movement. Nigerian culture always tries to police you and keep you in a certain structure and I think that the alté scene, for a lot of people, represents freedom to be themselves.

Mowalola: There’s a whole demographic of girls [in Lagos] who wear the same thing. They do the same French curl braids, and that’s nice because I know they feel most comfortable doing that. I’m never like, ‘You should do this and act like this’ – I feel like that’s true to them. People who want to try things that are outside the box should also be given leeway to express themselves freely.

How do you feel about the youth uprising in Lagos and west Africa more broadly?

Mowalola: With [anti-police corruption movement] End Sars I went to the protest at the toll gate and I have never seen energy like that with young Nigerians before. It was like our own park – everybody was there chilling with each other, playing music and tidying up. I had never seen that many young people all in the same place; I’d never felt so free. And seeing how that ended, with so many people who were not even being aggressive or violent being killed, made people more scared to go out. I have gay friends in Nigeria who have to change before they get to where they’re going because when they take public transport the police stop them. It feels like everything is trying to stop you from feeling like yourself. With the things I do, even the things Tiwa creates, we get people to question what they are conditioned to think so they can figure out shit for themselves.

Tiwalola: You do the degree your parents want you to do, you get a job your parents want you to get. Well, the thing is, your parents have lived their own life, right? At the end of the day, who’s sitting in that lecture hall? Who has to write the exam? You. I think it’s one of those things where you only have one chance to live the life that you want, and you will feel so much pain and regret if you never give yourself permission to explore and be free and follow your curiosity without caring too much about what other people think. Life is a journey. You’re meant to evolve; you’re meant to grow and try new things. You have to question any kind of voice or culture that wants to keep you stuck in a specific box, playing a specific role your whole life.

“I’ve been cancelled so many times. The first few got to me… but once I overcame it, nothing anyone said online about me could hurt me” Mowalola

Mowalola: I remember I was in Central Saint Martins before I went on a year out and I applied to all these houses, and they all rejected me. I thought I had failed at life and I was in my room crying and I was speaking to Mum and she was like, ‘this is OK. Failure is a really good thing because then you overcome it and you only get stronger so you can pour more energy into things that you want to. Don’t see this as your design future being over because Margiela didn’t accept you.” In my year out, I feel like the things I did helped me to figure out who I was and how I wanted to do my final collection. So, those big names didn’t mean much because I think the little places I went to, I got to do a lot more. I got to find out a little more about creating a collection and how to put yourself into it, how to talk to people with your clothes. I love failing. I feel like it’s the biggest vibe ever.

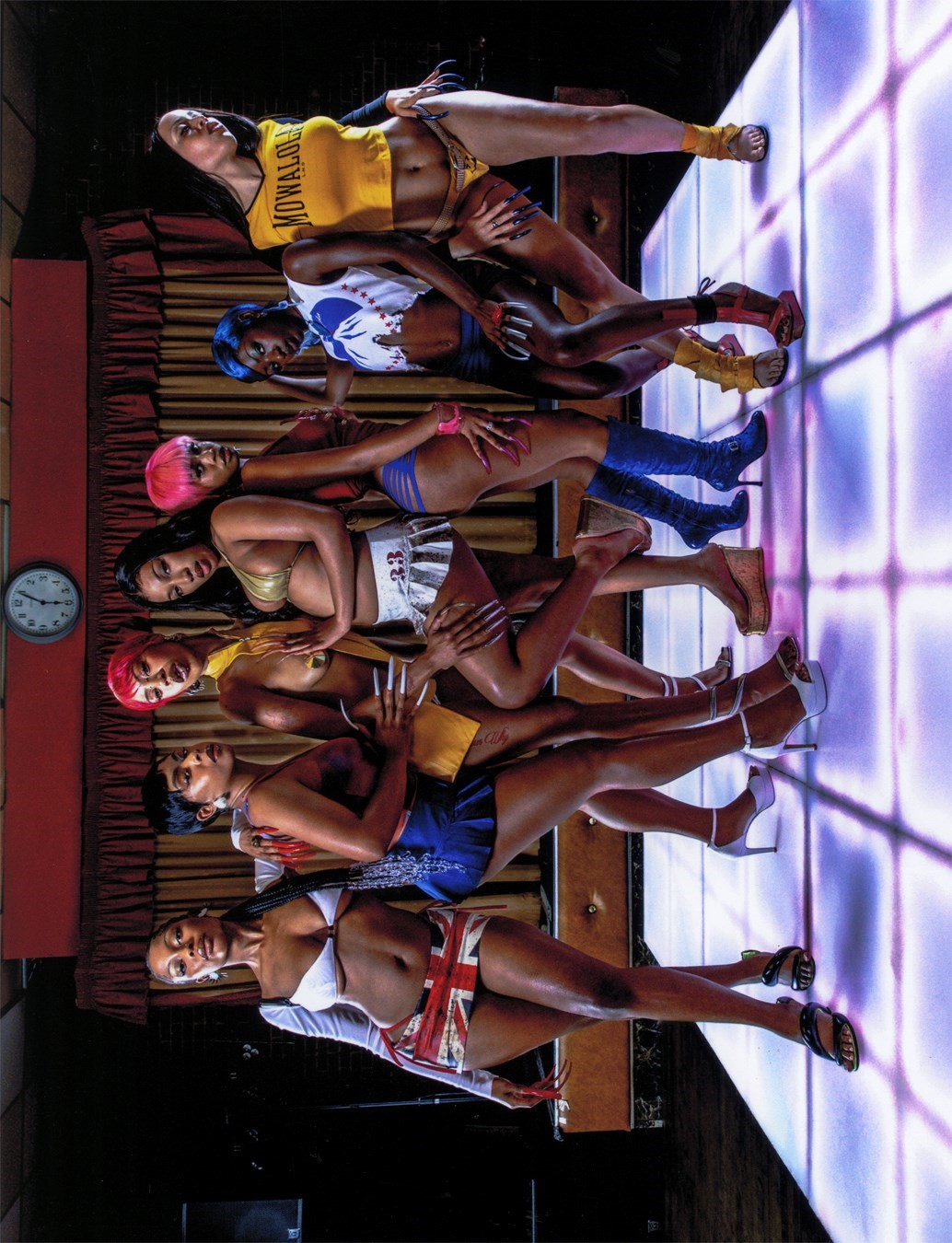

Tell me about the cast of Nigerian baddies you brought together for this story.

Mowalola: Sometimes you meet people and it feels like you’ve known them in a past life. With Ceechynaa, when I heard that music I was like, ‘Whoa, who’s this bitch?’ When I saw the video [“Last Laugh”] of her walking down Oxford Street with the tiniest bikini on I fucking loved it, because you don’t really see female rappers in London going out of their way to do something different. It was refreshing and I wanted her to walk in my last show but it didn’t work out. She called me up a week before the show and we had this three-hour conversation about the industry, about what she’s doing, about music and wanting to stay independent and do things differently which is how I feel about fashion. Chi [Virgo, musician] and Deto have been inspiring me my whole life. I met Chi during lockdown but Deto I have known since I was five and they are girls who make me feel really safe. I feel very protective of them – Ceechynaa and Wunmi [Bello, influencer] as well. I want people to see this demographic of Black women that exists; we are so multi-dimensional. Lola [Akinrele] is a younger Nigerian girl that I met two years ago, but I heard this song she did and I was just like, “Who the fuck made this?” I think she has a very interesting eye, with how she dresses and even the music that she makes, she inspires me.

How did you feel about Wunmi going viral in one of your dresses?

Mowalola: With Wunmi, I only found out about her when that whole dress drama happened. I love how she didn’t give a fuck because we designed that dress thinking it’s revealing but it’s for the girls who want to do that. Seeing her wear it with such confidence, it just showed she’s that woman, she doesn’t give a fuck. She’s gonna do what she wants to do and the clothes give her that confidence, that power, you know? You’re channelling sex differently. It’s not directly through the male gaze. It’s through your self-esteem. What about my body is so offensive? I don’t see it that way. The body gives life. This body is beautiful. Even with my Saudi skirt, I did that skirt so I could be inclusive to the girls in Saudi Arabia who also feel like they align with the things I do. I like the [idea of] using your sexual energy as confidence.

Controversy has sometimes come your way because of this – with the Saudi skirt, for example, or the gunshot wound dress that Naomi Campbell wore. Is there anything you regret on second thought, or do you stand by those decisions?

Mowalola: I’ve been cancelled so many times. The first few really got to me but then I felt like those were necessary for the things that were to come because once I overcame it, nothing that anybody said online about me could hurt me. When the biggest one [the Saudi skirt] came I was numb to everything, I was looking at everybody’s comments, like, I feel bad for you. I’ve apologised on my Twitter. I don’t believe that I was coming from a place of malice and I did not do anything violent towards anyone. I think that the way people spoke to me over a skirt should be spoken about. You’re telling me to die, telling me you hope my mum gets raped. You need to have grace for other people so you can have grace for yourself. After my show, I felt joy. Like nothing anyone could have said could take me out of that joy. And I hope other people can feel that when they create something and see it fully realised because that show almost didn’t happen. We had no support to do the show at all then at the last minute, [Ye] came and he was like, ‘[I’m] gonna pay for everything’. And I think, what if that show never happened? I can’t see life without it.

How is it for you at present as a woman in fashion? The headcount at most houses is predominantly white and male. Do you ever see yourself at a fashion house?

Mowalola: Do I want unlimited support for my ideas? Yeah, I do. I feel like having a house gives you the safety of being able to create. I could create all day but then I’d have to expand my business because I’m a startup, basically. My sister knows what we went through this year, it can put you in a dark place. Before you can even create you’re thinking about what you can or can’t afford when your mind is supposed to be fluid. I’ve had to figure out how to be on top of my businesses but balance [that with] being creative too. It took a lot of tears to get there. The things I’ve been through have allowed me to grow and I would love the opportunity to create without having financial woes on my back.

Which house would you like to go to?

Mowalola: I’m interested in McQueen, Burberry and even Givenchy. Vivienne Westwood would be fun. Tom Ford would be badass. Me and my design team, we’re chameleons because we like a lot of things.

How can we start making the right shifts in the industry?

Mowalola: The right person putting people forward. I feel like in these rooms where they discuss things, there are not any Black women there. To change those things you need more people of colour in those rooms. I feel like I’m way more talented than people who are at heads of houses so it’s not even really a talent thing. I feel like it’s just who you know.

You mentioned Ye earlier, and how he supported your last show. I noticed he even played some unreleased music at the show.

Mowalola: Yeah, the soundtrack was shorter than the show’s running time. My producer told us this, like, 20 minutes before the show and I was talking to [Ye] and he was like, ‘Oh, well, like what about this song?’ And I was like, fuck yeah! I like working with him because he is very spontaneous. He has taught me so much about creating in a way that suits you and not what the industry standard is pushing.

“I’ll get things saying, ‘You’re the pulse of London’ and that’s nice but where is the support behind that statement? You can’t use me for the things I put out and not fully support the things I’m doing” Mowalola

How did that relationship start?

Mowalola: I was in the MA programme at CSM having the most miserable time ever and then I got this email [saying] Kanye wanted to call me and I was like, OK! He called and we had an hour-long conversation about a lot of bullshit. Then I went out to LA to see if [working with him was] something I would do. At that moment I felt like I still wanted to figure out who I was and what I wanted to say, so I didn’t work with him then. He called me again but I didn’t want to work with him then [either] and then in lockdown, when he asked me to do North’s birthday, I was like yeah, and he offered me the Gap job afterwards. That’s when we started working together and we’ve had a lot of conversations about many different things over the years, so I really understand his design language. He also gets mine and even though we don’t do the same things, we love what each other does.

People will have negative things to say about your relationship with Ye because of some of his prior remarks and behaviour. What have been your experiences with him? Why have you maintained your relationship despite everything?

Mowalola: What I appreciate from people is their realness. Whether it’s bad or good I just appreciate everyone being real and I feel like in the fashion industry, nobody is real. He’s very free and we could have disagreements and it’s OK, we can talk everything through. You don’t have to agree with everyone but he’s also been – apart from my parents and my sister and my community – the only person who’s supported me in this business. He’s helped me see my dreams come true, and I appreciate that. If not for him, I would lowkey be dead in the water. He’s one of the greatest designers ever yet people don’t want to give him his flowers; they keep trying to marginalise him. I feel like he doesn’t want that same thing to be my story. He wants to make sure I also get the opportunities I deserve. I’ll be getting things saying, ‘You’re the pulse of London’ and that’s nice but where is the support behind that statement? They won’t try to support the things I’m doing but they’ll ask me to put my media in a slideshow at their event. You can’t use me for the things I put out and not fully support the things I’m doing. So instead of banging the door I just left it and found joy in my community. That’s why with my show I didn’t really care about what editor was there or not. I just wanted the people who fuck with my brand to be there and experience the show.

Your shows always do feel intentional in that way.

Mowalola: I figured out new ways to work in my business so I don’t have to do the things they say you have to do, because I tried it and this fashion system isn’t actually working out. It’s not built to support upcoming brands. It’s built for the bigger brands and stores – the payment terms, the percentages, the sales people take off your orders. Everybody takes so much, but the person who creates the product gets nothing. I feel like there isn’t much respect for creatives overall in this business. I have people reaching out to me for customs and their budget is a thousand, but they want me to make an outfit in four days? Like, what? It’s not making sense to me but I have worked with musicians who fully understood the value of what they get by working with me; people like Drake, Rihanna, Kanye. So I just stay working with the people that invest back in me. [Later in our conversation, Mowa comments about working on customs with celebrities: “They’re like, ‘You should want to do this; you should be dying to do this’ but it’s like, ‘No, I’m dying to keep my lights on. I’m dying to be able to create the things I want to create.’ I feel like if I lower the bar to accept certain things then nothing will change.”]

How important is your team and wider community to what you do?

Mowalola: I want my team to feel valued. I want them to feel like they’re doing something worth their time. I want them to feel it’s like this now, but next year will be better and the year after that will be better.

Tiwalola: I think community is a lifeline. It’s about being of service to something bigger than yourself. It’s about leaving legacies. I keep that at the centre, but also community is what keeps me going and what keeps me alive. I love what Mowa was saying earlier about having an abundance mindset, and when we think abundantly there’s enough room for everyone to thrive. We see people with empathy and compassion and we’re shining our light to lift others up into their own light too. That’s when we begin to form beautiful communities where greatness is unlocked in all different places; it’s like a domino effect of all of this goodness and positive change happening in society.

How would you define a baddie? What does it mean to be a baddie today?

Tiwalola: Someone who is awake to the greatness inside of them. No sleeping on yourself, you’re awake to your worth and you’re unapologetic about living that out. You’re confident. You go after what you want. That’s a baddie.

Mowalola: I feel like a woman who loves Jesus Christ is the realest baddie ever.

Tiwalola: I agree, amen to that. Are you expanding on that, Mowa, or is that a one-liner?

Mowalola: That’s it. I said what I said!

Hair AMIDAT GIWA at BRYANT ARTISTS using WELLA, make-up ISAMAYA FFRENCH using ISAMAYA, nails YUIKA YONEHARA at HACO+, talent MOWALOLA, CEECHYNAA, TIWALOLA, LOLA AKINRELE, DETO BLACK, CHI VIRGO, WUNMI BELLO, set design JACK APPLEYARD, photographic assistants MILAN RODRIGUEZ, EVIE SHANDILYA, stylist assistants ALIOU JANHA, JESSICA SHARP, hair assistants AVRELLE DELISSER, FUNMI ORIOLA, make-up assistants TASH SULTANA, JOE BROOKES, nail assistant MAHO ISHIKAWA, set design assistant CHLOÉE MAUGILE, digital operator GREG HOLLAND, production NOIR, post-production THE HAND OF GOD, casting MISCHA NOTCUTT at 11CASTING

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.