Janyce Denise Glasper sees an exhibit by Njideka Akunyili Crosby in New York at David Zwirner Gallery. The artist, whose paintings are loosely autobiographical, includes Xerox transfer images added on, which create a surreality and veiling. Of the artist’s complex technique, Glasper says, “She is simultaneously generous and giving yet mysterious and protective.” The exhibition ends tomorrow (Oct. 28, 2023), with gallery hours from 10AM – 6 PM. Run over and catch it!

I had always wanted to move to Philadelphia — the catalyst strongly ignited by that first virtual sight of Njideka Akunyili Crosby’s impressive work on the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts website. While I lived there from 2013-2019, the artist became a great enigma to study, contemporary books placing her refreshing voice among painters such as Kehinde Wiley and Kerry James Marshall. I would see a singular physical piece here or there— Philly or Harlem— with a desire to see more from someone clutching Nigerian in one hand while grasping Americana in the other. Five years ago, fate (under the guise of the problematic Greyhound bus) robbed my dreams of a room full of her mixed media paintings at the Baltimore Museum of Art, by failing to get me to the show before it closed. It took forever to recover from that devastating loss.

Coming Back To See Through, Again at the David Zwirner Gallery in New York certainly arrived at the right moment— my art writing focusing on applying Alice Walker’s concept of womanism to the work of Black women figurative painters in exhibits around the world. Womanism by shorter definition means both a Black feminist and a woman who loves other women, sexually and/or nonsexually. This year, Faith Ringgold took over Paris at the Musée Picasso, Lynette Yiadom-Boakye ruled Guggenheim Bilbao in Spain, and Danielle McKinney, Somaya Critchlow, and Kudzanai Hwami-Violet shined in their respective solos across the United States and London. Njideka Akunyili Crosby’s latest exhibition fits well alongside them— as do so many in a continuing line of creative Black women, past, present, and future. In a journal entry (edited by the late Valerie Boyd), Walker wrote, “the womanist tradition assumes that Black women can do almost anything– because they usually have already done it–” especially pivotal to apply in the context of art. In another essay, One Child of One’s Own, she revealed, “I was astonished, after reading [Judy Chicago’s Through The Flower], to realize she knew nothing of Black women painters. Not even that they exist.”

So, I crossed my fingers hoping for a safe flight [from Dayton, Ohio] and gentler rain. On a Saturday afternoon, braving a torrent of sloshing weather, I walked alongside a phenomenal talent, Ify Chiejina, continuing my sacred birthday tradition of viewing a Black woman artist’s work in person. We conversed about Njideka Akunyili Crosby’s nine paintings clinging to the wall on clipped hooks, unstretched, made from 2019-present. On the wall, the evidence was clear as day, we witnessed a painter pulling us into her authenticated world, shedding resplendent light on subjects that mattered so passionately to her.

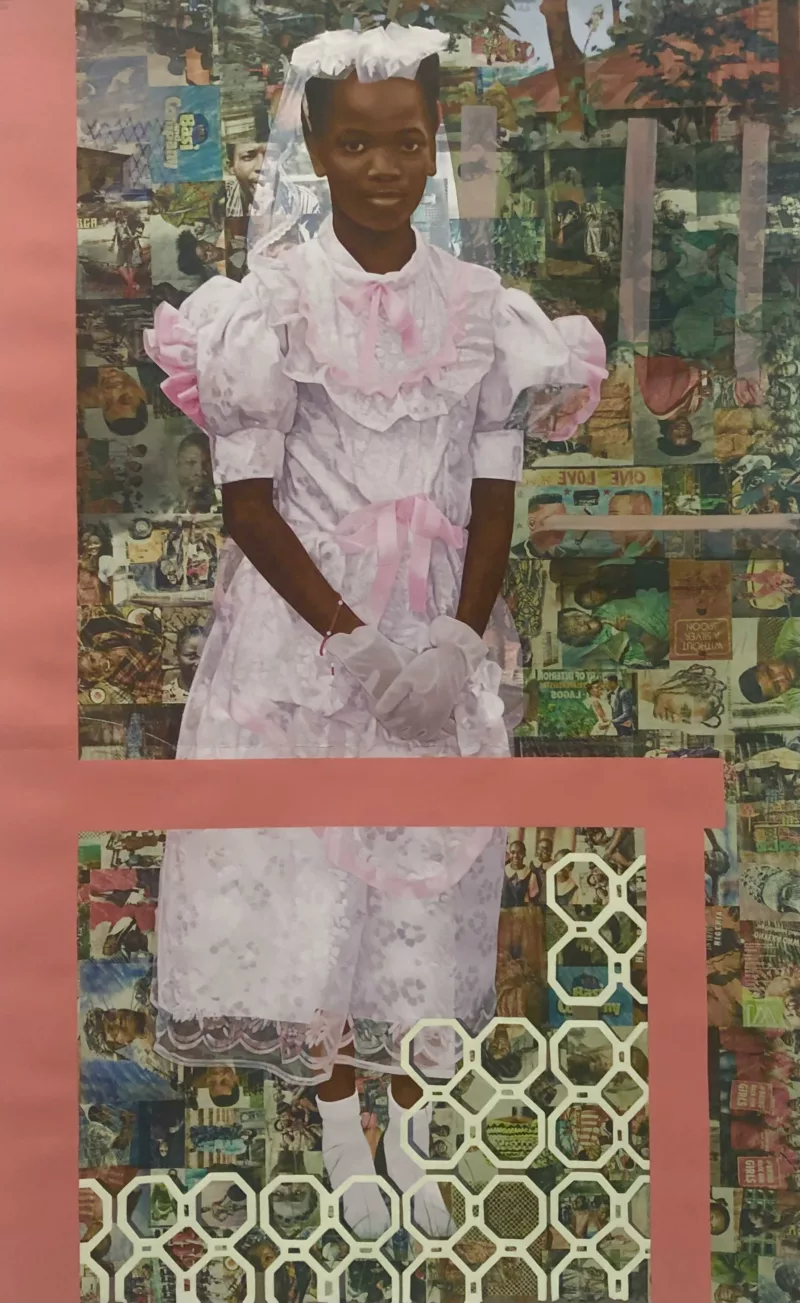

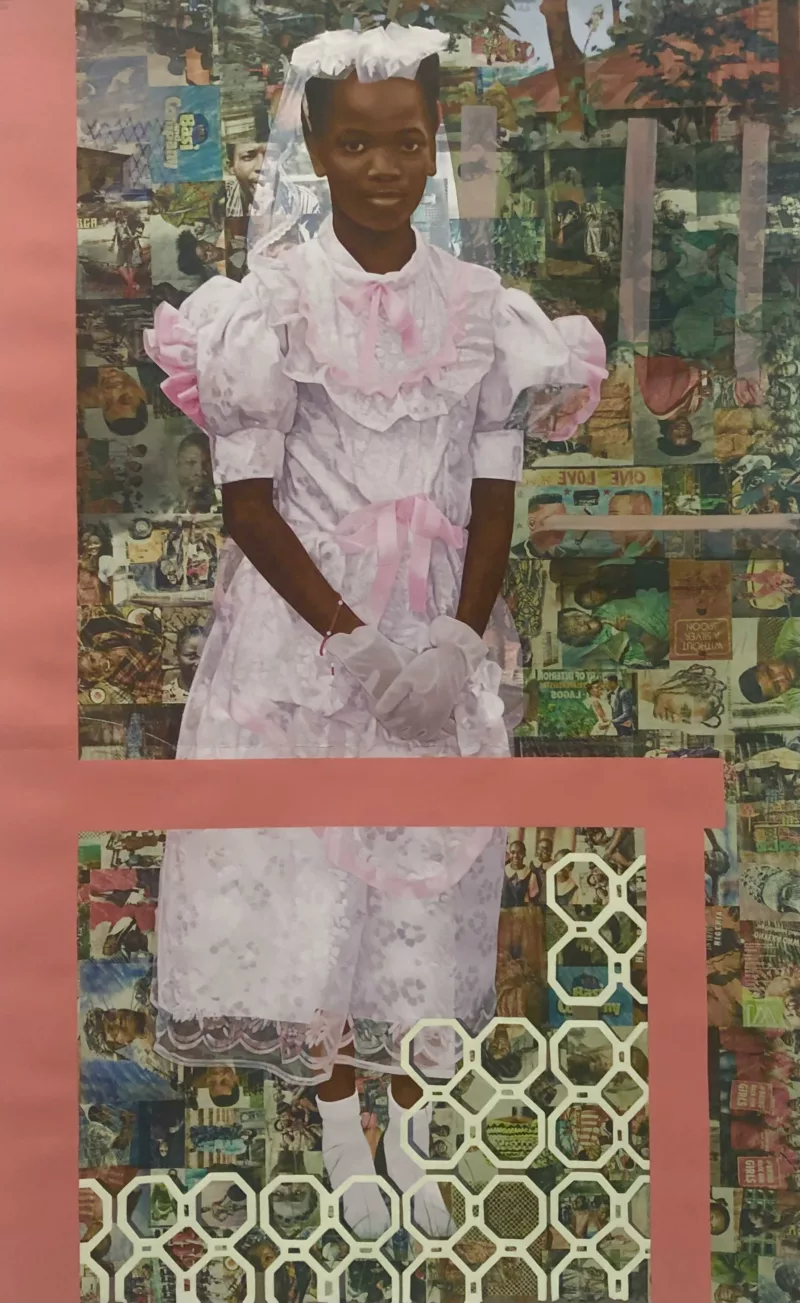

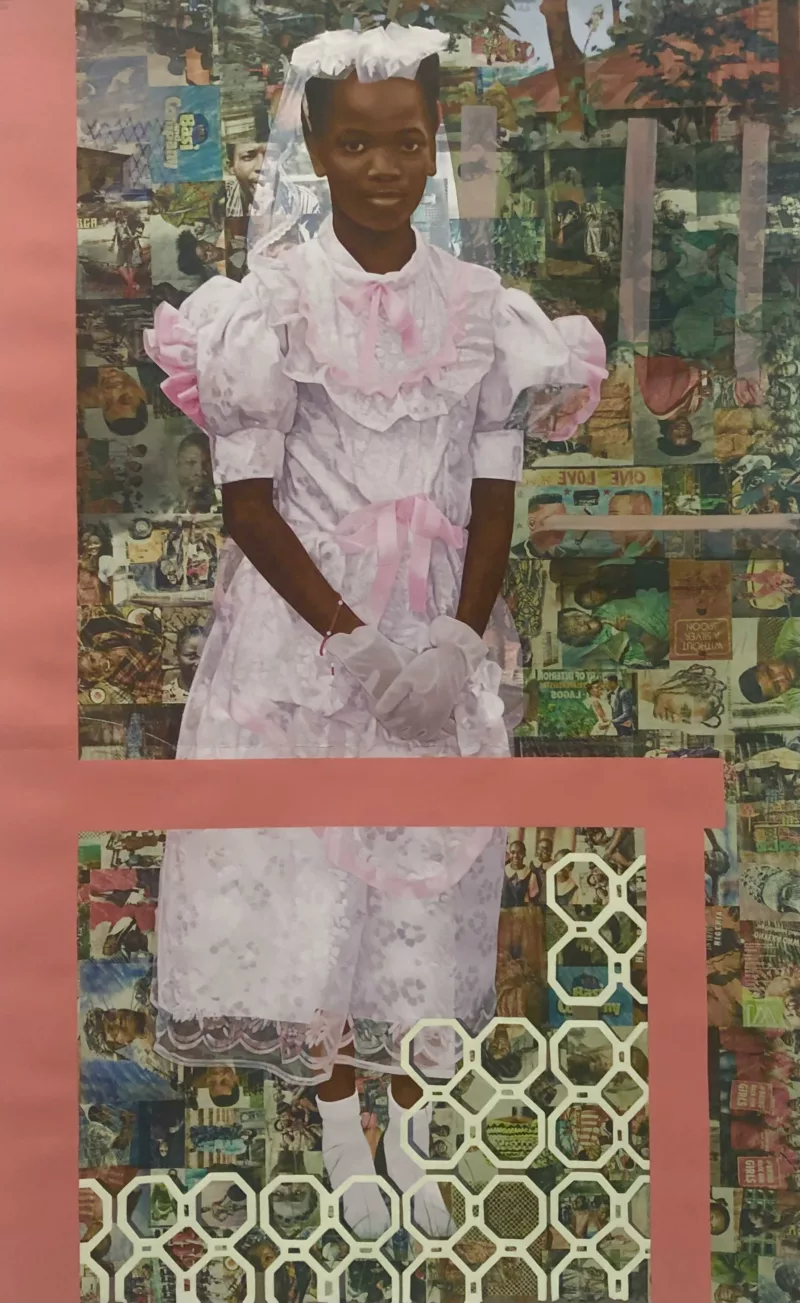

From the 19th Street entrance, “The Beautyful Ones #11” takes the left side and invites sentimental reflections. The large piece of acrylic, colored pencil, and transfers on paper centers a poised Black girl wearing immaculate debutante attire— a younger Akunyili Crosby. Her gloves, dress, veil, ankle socks over shoes are a starched white symbolism of purity and humble regard. Pink bows accentuate that immense grasp on girlish innocence while her expression almost conveys both uncertainty and softness. She stands beside a fence, a controlled painted body surrounded in an ordered chaos of seamless xerox faces. The realist meticulousness demonstrates the artist’s extreme attention to detail, her mastery in acrylic paints and colored pencils. The accuracy in flesh, in dress— it shows diligent care and respect. Yet, the remarkable symmetry in the composition perhaps presents her personal duality, existing between two worlds that make the work even more honest. Upon closer inspection, the gathered Xerox transfer images contain people donning traditional Nigerian clothing. Their precisely cut portraits are in different orientations– sideways, upside down, right side up. Weddings, dates, graduations, and hairstyles of beauty salons and barbershops are among the representations.

Among the meticulous brushstrokes and collaged transfers, Walker’s womanism wanders everywhere, mainly employing the many roles Akunyili Crosby makes known— being the author of her specific time, balancing various loving relationships, living in a future with the past always remaining a crucial part of life, and aligning Black identity and African heritage together. It may seem that all the works become jarringly packed with significant symbolism to decipher— no. Instead, the beauty arrests the eyes into the world of suspenseful awe. We never want to stop looking at the planes of flat negative space enriching the precious nature brilliantly weaved into her stories. She is simultaneously generous and giving yet mysterious and protective. In some works, the Xerox transfers are the primary evidence of the figure.

For example, “Dwellers: Native One” and “Dwellers: Cosmopolitan Ones”– made three years apart– figures hide beneath wild labyrinths of repeated geometry. The fence structure remains a constant vehicle. Both pictures operate a surrealist approach, playing with gestural shapes as the main focal point. Patterns compete for overlaying dominance in and out of realist brushstrokes and adhered images. The sophisticated intertwining encourages the viewer to wander between, to search for faces and take pleasure in their found joyful expressions. While both works employ a candid interest in tightly rendering plant form, the muted color palette in “Native One” tests green and yellow hues and “Cosmopolitan Ones” contains vivid experimentation, surprising pieces of luscious pink flowers breaking up the aquamarine and teal.

Furthermore, humanity takes on a unique form in “Ejuna na-aga, ọ kpụlụ nkọlikọ ya; New Haven (Enugu) in New Haven (CT)”, Igbo that translates to “Ejuna was going, he curled his elbows.” The composition focuses on an opened closet— possibly inside of a bedroom. Wax patterned clothes mingle alongside a plastic bagged wedding dress. The clothing highlights the unseen wearer while masterfully depicted objects randomly situate on tables– kerosene, two striped kettles, and a vintage copy of Eddie Iroh’s Without a Silver Spoon novel, a book on honesty. A wax fabric jacket’s shadow cuts the piece in half, almost forming a strategic diptych.

Akunyili Crosby expresses further intimacy in “Still You Bloom In This Land Of No Gardens” that occupies the rear of the gallery alone. In this grand-scale self-portrait, she holds a child on her lap whose golden-brown skin contrasts against her darker complexion. While the maternal figure dons a patterned native dress celebrating her ancestral upbringing, the child wears a baby blue “Black Is Beautiful” t-shirt and denim jeans— highlighting that the mother was raised in one culture and the child in another. Plants threaten to consume them, already cutting into the boy’s face, as protective as the maternal clutch. She looks out defiantly, her direct gaze daring anyone challenging the obvious love between a mother and her son. This openness clashes against an earlier painting “Blend In– Stand Out” that positions two faces into each other– the woman purposely cloaking the man with her body.

Although I no longer reside in Pennsylvania and have dreams of returning someday, this New York City journey comes across as a full circle moment, a devout testament of women supporting women. Coming Back To See Through, Again will stay permanently lodged in my memory as a worthwhile beginning towards continuing to view Njideka Akunyili Crosby’s craftsmanship in person. Virtual sites and book pages always fail to show the true degrees of artistic effort. Thus, Alice Walker instructs that we have a huge responsibility, an obligation as more than viewers. The importance of using our words to illustrate things seen, to document the impressions placed upon us when historically we were not given the tools to do so. A glance around David Zwirner Gallery gives an artist the necessary breathing room to let these nine pieces form rich, engaging dialogues. Akunyili Crosby’s signature style still retains innovative three-dimensionality, embarking on some new territory with intricate narratives, laborious technique, and moving vulnerability. We glimpse at the old while shifting into another era where transfers on paper can take us. The artist single-handedly proves that this experience is well worth the wait, the inclusion, and bears to be repeated.

Njideka Akunyili Crosby’s Coming Back To See Through, Again is up at David Zwirner Gallery, 519 W. 19th Street, New York City, NY until October 28, 2023. Gallery hours on Saturday, Oct. 28 are from 10 AM – 6 PM.

Works Cited

Gathering Blossoms Under Fire: the Journals of Alice Walker, 1965-2000 Edited by Valerie Boyd.

In Search of Our Mothers Gardens: Womanist Prose, Alice Walker.

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.