The British designer Phoebe Philo turned 50 last week, and today, at 11 a.m. ET, her namesake brand opens for business online after more than two years in development. Both events are milestones of a kind, for Philo is the first major designer in a very long time to put her own name on a label. In early October, I went to see her and her new collection in her London studio. I was one of a small number of journalists invited to preview it, all under conditions of secrecy.

To be sure, many people don’t know Philo’s name, though they might have worn her designs. From 2001 until 2006, she was creative director of Chloé, a Parisian fashion house founded in 1952 in the same spirit of youth and freedom that absorbed the existentialists and that Philo used in the long tradition of female designers: to liberate women. Her clothes were cool and stylish but uncomplicated, characterized by an English spunk and indifference to convention: baggy, tomboyish shorts worn with camisoles and stiletto boots; wide-leg, hip-hugging trousers cut to the waist for a lengthening effect, paired with the emaciating gauze shirts of a rock star; airy cotton dresses, based on old ruffled shirts, worn with wooden platforms.

Philo was part of a New Wave of young talent, along with John Galliano at Dior and Marc Jacobs at Louis Vuitton, hired by luxury conglomerates to juice up old brands, but she didn’t do anything that a daring designer was expected to do. No extravagant shows, no fantasy creations, no conceptual tricks. Her approach to fashion was more straightforward, focused on women her age. Chloé’s shoes and bags — the frumpily named Edith and the Paddington — became modern classics, and the mile-high pants launched an army of women who looked like elegant cranes loping down the street. Philo became celebrated for her unerring instincts. But as she said, invoking the standard of great female designers since Coco Chanel, “I’ve always had a sense that if I can’t wear it, what’s the point?”

At the end of 2005, she decided to leave Chloé and take a hiatus. The year before, she had married a London art dealer named Max Wigram and had given birth to the first of their three children. She was frank about the pressures of her life, admitting, “Leaving Chloé felt like the most honest thing for me to do — for my integrity, my husband, and my daughter.” Philo was also foreshadowing where the industry was heading: As big-name brands have become bigger, reaching about $10 billion to $15 billion a year in sales, and as the number of shows and products (and the hoopla around them) has increased, there has been a steady loss of freedom among designers. You see it in the repetitiveness of styles, the lack of newness. This is more true today than it was in 2005 or even in 2008, the year that Philo returned to fashion as creative director of Celine, an LVMH brand.

When she joined Celine, she got LVMH to build a studio in London so she wouldn’t have to commute to the brand’s Paris headquarters. She took more than a year to develop her ideas, and when she held the first show in October 2009, the atmosphere in the room was electric. As one writer put it, “We were all waiting to see what she would do.” That sense of anticipation never waned over the next eight years, but the biggest change in her work since Chloé was that Philo was now designing for a grown-up, like herself, with kids and more surly thoughts — Fuck it, I’ll wear that old raincoat — and, as well, more sophisticated tastes. I remember sitting at a show on a sunny afternoon in 2012, the windows of a Paris apartment flung open, and looking at sleeveless silk tees with black satin pants flopping messily over Birkenstock-type sandals lined with mink, a “very Phoebe” touch (and later a big trend), and thinking, Goddammit, she wants to escape? Go to the coast of California! Take me with you!” Her clothes usually had that transporting effect. Yet unlike many of her peers, she rarely reached for lofty references or themes; instead, she followed moods and hunches — with amazing accuracy.

Perhaps the reason that Philo was able to keep her audience in thrall for nearly a decade, while also causing Celine’s sales to quadruple to $846 million, is that she put few constraints on her style. Which is not to say that Celine was without an identity or signatures, like, for example, her minimalist, masculine coats and oversize cotton shirts. But she allowed the style to develop as it went, “step-by-step,” as she put it, “with no great strategic plan.” Thus the designs always remained alive and surprising. And as a creative person, Philo once suggested, that freedom was vital. “I feel very much that I am a human being, with human limitations, and I need to respect that,” she said in 2010. If fashion insiders wondered after she left Celiné in 2017 whether she’d ever apply her instincts to another house — Chanel was the favorite hope — she had already given them her answer.

At Philo’s spacious studio, I spent nearly two hours with the clothes and accessories, which were arranged on four or five dress rails and several large tables. No photographs or recording devices were permitted, and I was asked not to reveal that I was even there, though this rule was lifted in order for me to make it clear that I saw actual clothes and accessories, and not images of them.

Why all the covertness? Obviously, it seems to add further intrigue to a brand people have been speculating about for more than two years, since Philo announced it with a brief statement in July 2021. But she has always been a reluctant interview subject, and there were moments at Celine when she closed the backstage to reporters. To me, what the control and protectiveness suggest is a person trying to do things, finally, on her own terms and maybe in the process show that it’s not impossible to create a new and better business model. To that end, Philo chose to not launch her brand with a blitz of interviews and instead let the work speak. And of course, there’s a more mundane explanation for the secrecy: The collection is going to get copied the moment it’s public.

Almost as soon as I began pulling out the clothes, I had the impression that I was seeing something completely new and, more, that fashion had taken a big step forward. It was the kind of movement that people have been waiting for. And I must admit that her ideas made the work of some of her peers look rather contrived.

Philo has organized her brand around the principle of a wardrobe or, as the company said in a brief press note, “a seasonless, continuous body of work.” That doesn’t just mean a classic coat or pantsuit that will look good for years; it also means a distinctive point of view, a style, that you can continue building on. Philo had tried to apply the principle to Celine, but, in hindsight, she often muddled her intentions with too many conceptual pieces, like a series of coats she did in 2017 that were double layered and weirdly formed a fat loop around the hem. Her new line doesn’t make that mistake. This is the biggest change in her work and the most thrilling and liberating: She’s eliminated anything that doesn’t feel essential, cool, and brave but not ridiculous. It’s the ultimate modern wardrobe from a dissatisfied woman.

At Chloé, Philo had brought to the clothes a Brit-party-girl sensibility, but she moved away from or grew out of it at Celine, where the look became more covered-up and serious. Her newest collection, though, balances comfort with sexiness, masculine tailoring with edgy separates. She has a wonderful dress in ivory silk satin that is cut to the top of one leg and is little more than an oblong square with slit armholes and a high neck. To make things easy, she built a bodysuit into the dress, which could double as a tunic to wear with pants. The design reflects changes in Philo’s own thinking as it resolves how to make a party look feel hot as well as comfortable and modern. And consistent with her sharply focused wardrobe idea, she doesn’t offer you five variations of the dress, as many brands would; she gives you just one.

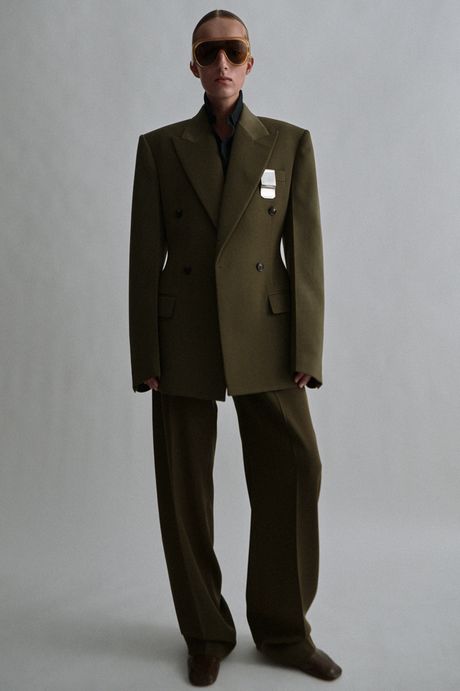

One of my favorite outfits, a drab olive-brown jacket and a matching pair of baggy pants, might well have been based on army surplus fatigues. But because of the detail of a high, chin-grazing collar and the soft drape of the fabric — a result of multiple washings, a technique Philo used often — the outfit struck a nice harmony between style and utility.

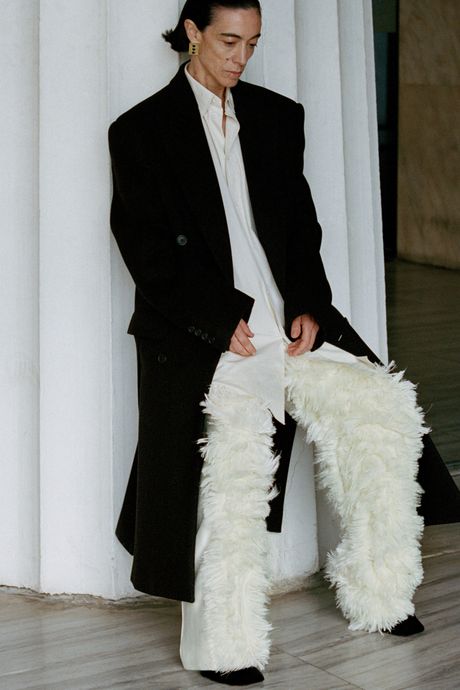

Those kinds of considerations run through the collection. How do you make a tough leather jacket without it looking like everyone else’s on the market? Philo offers several distinct styles. One is a blouson with wide ruched or elasticated cuffs. The volume is generous, the black leather of a high quality, but the clinching detail is a fairly large leather scarf that you can wear draped at the neck and front and keep in place by means of two snaps below the back of the collar. It’s a simple gesture that transforms the style. The second jacket is similar in shape, but the front and the front of the sleeves are covered in leather fringe — not swishy cowboy fringe but, rather, flat tabs that measure about three inches long and an inch wide and are layered unevenly. The back of the jacket is completely smooth. And, finally, the third style reminded me of an East German cop in a Cold War thriller. It has a high funnel neck, rather beefy shoulders, and an elasticated, dropped waist that gives the tough coat a bit of skirt. There is, in fact, such an appealing toughness about this collection, reinforced by the models she’s chosen. And that’s also something new.

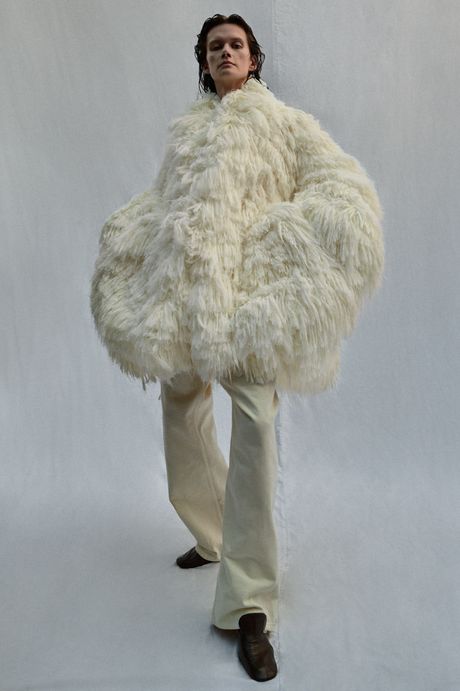

Her pants are sensational. I can’t wait to see someone in an off-white pair — smooth through the hips, straight-line, somewhat crinkly in texture from washing — with a zip running up the back of each leg, from hem to waistband. Another style, offered in either black or white viscose, has a long, neat panel of fuzzy material (hand-combed viscose) embroidered down the front of each leg. I’ve never seen anything like them. To show how versatile the pants are, she styled them in images with both a wool coat and a slightly oversized cotton shirt. In a similar mood, Philo also has a black mini skirt that has a wide, curling, kelp-like panel down each leg and is edged in the hairy viscose. She used the same fuzzy material, embroidered on ribbon, for a swaggering pair of coats. Made in Madagascar, they’re likely to be available in only a limited number.

People will discover for themselves that Philo’s label is expensive, though in line with many brands. The leather jacket with the scarf, for example, is $8,900. A berry-wool suit is $3,900 for the jacket and $1,900 for the trousers. The ivory silk dress is $2,000, while shoes range from $1,100 to $1,750. The company has a minority investment from LVMH, but it’s controlled and managed by Philo.

In a lot of ways, the significance of her return to fashion lies in her business model. The brand will release two collections, called “Edits,” a year, each comprised of three deliveries spaced over a few months. The first delivery will have the largest quantity of items. In today’s inaugural release, there are 150 styles, which is a pretty small number compared to what most luxury brands put on a runway. The company says that because it plans to have a responsible balance between production and demand, it means “producing notably less than anticipated want.”

Sooner or later, though, someone was going to show the industry that a designer can do amazing and meaningful work if they allow themselves time. And they don’t have to chase growth, which has turned once-creative fashion houses into machines of assembly-line luxury that discourage risk. Philo’s brand, though barely hatched, asks many timely questions. How big must a brand be to be sustainable? How much profit does it need? And how wise is it to keep producing all these preseason collections and extra commercial lines that brands claim they depend on?

Twenty-five years ago, Philo helped to create the industry’s new paradigm of young talents pouring their ideas into outworn brands. After seeing her free-thinking new collection, I now wonder if she’s about to destroy that paradigm.

Phoebe Philo’s Return Is a Wake-Up Call

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.

Leave a Comment