ARTS & CULTURE; COMMUNITY

By Diana Newton

Correspondent

For many of us, “portrait” calls up austere images of presidents hung on walls in gilded frames. And there are the ever-present selfies, which strip any seriousness from the art form. But in a new exhibit at the Ackland, “The Outwin: American Portraiture Today,” the 42 works now on display revise, expand, and even obliterate the centuries-old formal tradition of oil paintings featuring seated subjects with sober expressions.

Redefining what a portrait can be

The range of portraits selected for this exhibit is intentionally contemporary, as artists must have created them within the past two years, revealing how the tradition of portraiture is being practiced and challenged today. Since this cohort of artists was created between 2021-2022, the exhibit embodies pandemic-driven themes, such as isolation, loss, proximity or distance from family, intergenerational connections, and people and lives that are often overlooked. Collectively, the works expose the times we are living in.

Many of the Outwin portraits use unorthodox materials, as seen in Cherry, painted on a printed cardboard produce box.

Narsiso Martinez (Long Beach, California), Cherry, 2020, ink, gouache, charcoal, metallic paint, and other media on printed cardboard, 35 1/2 x 29 1/2 in. (90.2 x 74.9 cm), collection of Andrew Stearn. © Narsiso Martinez

Taína Caragol, Competition Director and Co-Curator of the Outwin has noted that this cohort of artists used a surprising range of unorthodox materials, from aluminum foil to a produce box to an excavated butcher’s tool. They also produced more large-scale works than in previous competitions. Their results challenge the very definition of portraiture, moving well beyond just capturing a face to convey nuanced life experiences, memory, and movement, sometimes with no face in sight. From any given angle in the gallery, viewers may see painting, drawing, sculpture, photography, textiles, video, and time-based art.

Standing beside Stuart Robertson’s closely cropped Self-Portrait of the Artist, Caragol pointed out his detailed crafting of aluminum and bubble wrap, earth and sequins to create only the lower portion of his face, while his eyes are excluded. Viewers’ perceptions of and assumptions about the artist are no doubt shaped by those missing eyes. In Timothy Lee’s A portrait of the comet boy as a bearer of memories, the boy’s eyes are suggested rather than clearly visible. His gaze is decidedly inward, as rendered among incised gold leaf cuts throughout much of the work’s surface. The boy’s haloed form radicalizes the liturgical tradition of haloed figures in this look at a young man grappling with his Asian American, queer, immigrant, and diasporic identities.

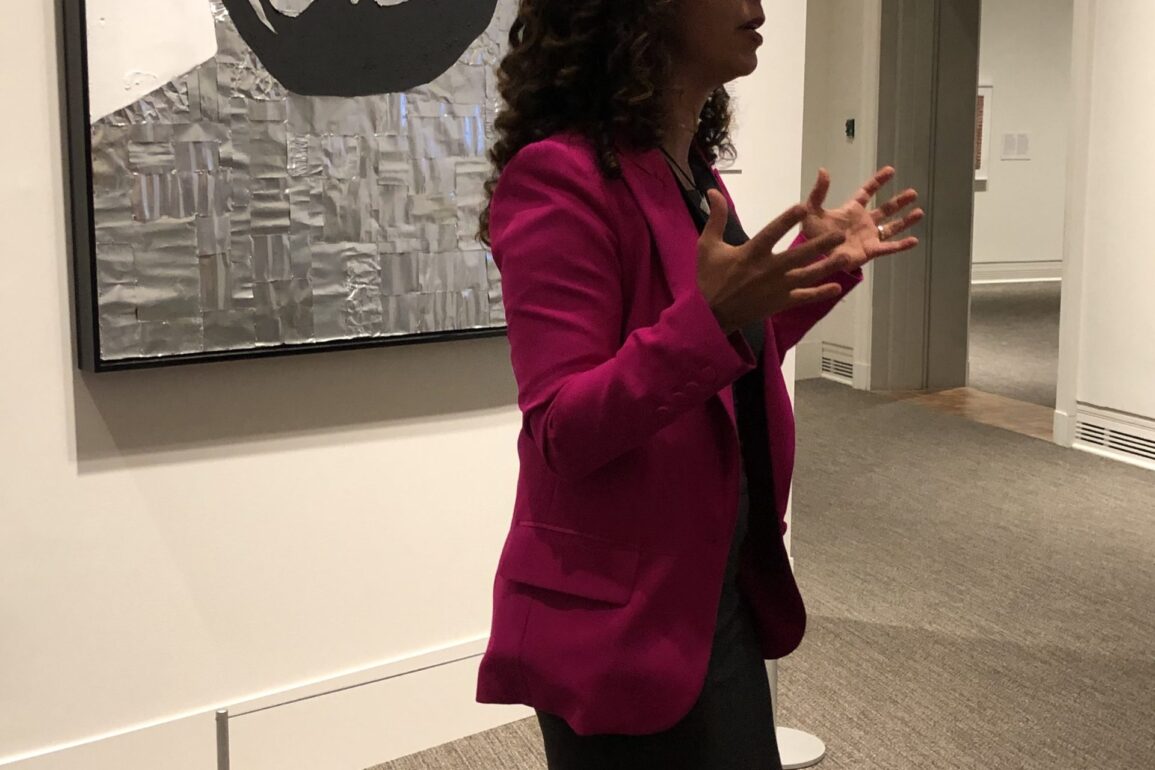

Outwin Competition Director and Co-Curator Taína Caragol discusses Stuart Roberston’s Self-Portrait of the Artist, at the new Ackland exhibit. Photo credit: Diana Newton.

Black Women Doing and Undoing

By contrast, in other portraits the subject’s gaze is unrelentingly direct, as in two of the digital video portraits that run continually in The Outwin. American Woman, by Holly Bass, a multidisciplinary performance and visual artist, and writer, explores Black womanhood, labor, and beauty in dual mediums – a 7-hour dance performance and a 16-minute video that distills its messages to a watchable length for gallery goers. Clad in a bright red jumpsuit accented with platform shoes and a scarf that sports an American flag design, Bass grooves and gyrates to sound clips of speeches by famous Black women activists, such as Shirley Chisholm, Fannie Lou Hamer, and Angela Davis. At other moments she pops and locks to the music of Nina Simone, Aretha Franklin, and Rihanna. All the while her scarf becomes punctuation and provocation – a cradled infant, or a brow-mopping handkerchief in her constantly moving hands.

A less energized but no less jarring 12-minute video portrait is the un-doing, by Adama Delphine Fawundu. In a liberation ritual, a confident young woman dressed in an elegant blue and black ruffled dress slowly unravels each of her two braids. Running her fingers through her freed hair, a voice-over repeats the mantra, “My love is too sanctified to have thrown back on my face” while an unsettling violin score proves as piercing as her stare. Both Bass and Fawundu chose to have their work mounted in ornate frames, claiming the visual space in a way that few women of color were allowed to occupy in the tradition of Western portraiture.

Grooming a Winner

The Outwin awards three cash prizes, highlights commended works, and offers a People’s Choice Award. The first place winner also receives the opportunity to create a commissioned work for the Smithsonian. For the current 2022 show, first place went to Alison Elizabeth Taylor for her large-scale work, Anthony Cuts Under the Williamsburg Bridge, Morning.” Created from intricate wood veneers, sawdust, and inkjet prints that she describes as “marquetry hybrid,” Taylor depicts the innovation and generosity of a barber working outdoors by a chain-link fence during the Covid lockdown. Taylor learned that hair groomer Anthony Payne donated the proceeds from his donation-based haircuts to organizations advocating for social justice, and chose to pay tribute to him using a medium once preferred by Louis XIV for his furniture.

This exhibit vigorously mines and upends the concept of portraiture and surfaces with a myriad look at the American experience that does far more than reflect our faces.

Diana Newton is a coach, facilitator, filmmaker, writer, artist, yoga teacher and general Renaissance woman. Her documentary film, The Ties That Bind, is available for streaming on UNC-TV. She lives in Carrboro and is a UNC alum.

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.