Born in American Presbyterianism’s western Pennsylvania hotbed, a child of Scots-Irish migrants devoted to the old United Presbyterian Church (Scotland), Rachel Carson became a stalwart environmentalist, a patient lover of nature’s beauty and a thorn in the side of government and industry. She passed nearly 60 years ago in Silver Spring, Maryland.

Carson’s Presbyterian roots go back a couple generations on both sides. Her mother, Maria Frazier McLean, was raised in the United Presbyterian Church of North America, graduated from Washington Female Seminary in Pennsylvania with honors in Latin in 1887 and taught school in Washington County. Maria’s father and Rachel’s grandfather, Daniel M. B. McLean, was a Jefferson College (Canonsburg) and Allegheny Theological Seminary graduate, and pastored Fourth United Presbyterian Church (Allegheny City) and Chartiers United Presbyterian Church (Canonsburg).

Maria married Robert Carson, a United Presbyterian minister and child of Fourth United Presbyterian Church of Allegheny City, in 1894. Five years older than Maria, Robert has been described as “slender and pleasant-looking” with a “thick, sweeping mustache in the grenadier’s fashion that he waxed into perfect sharp tips.”

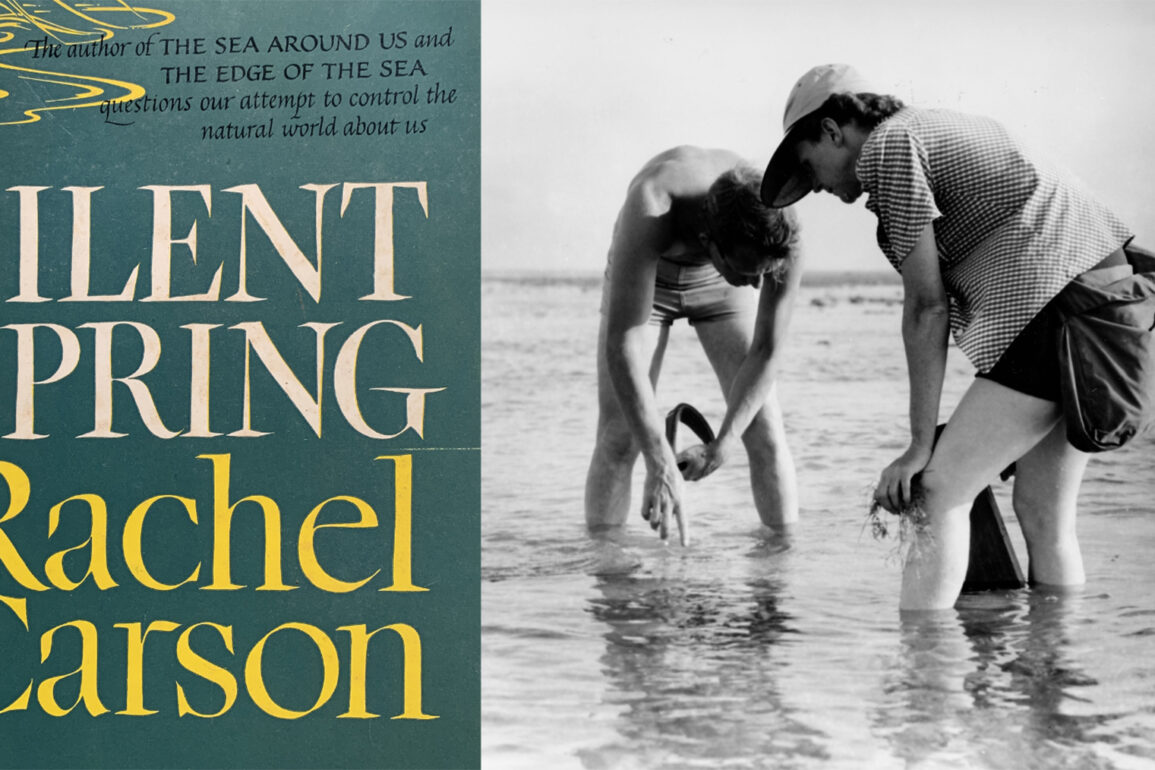

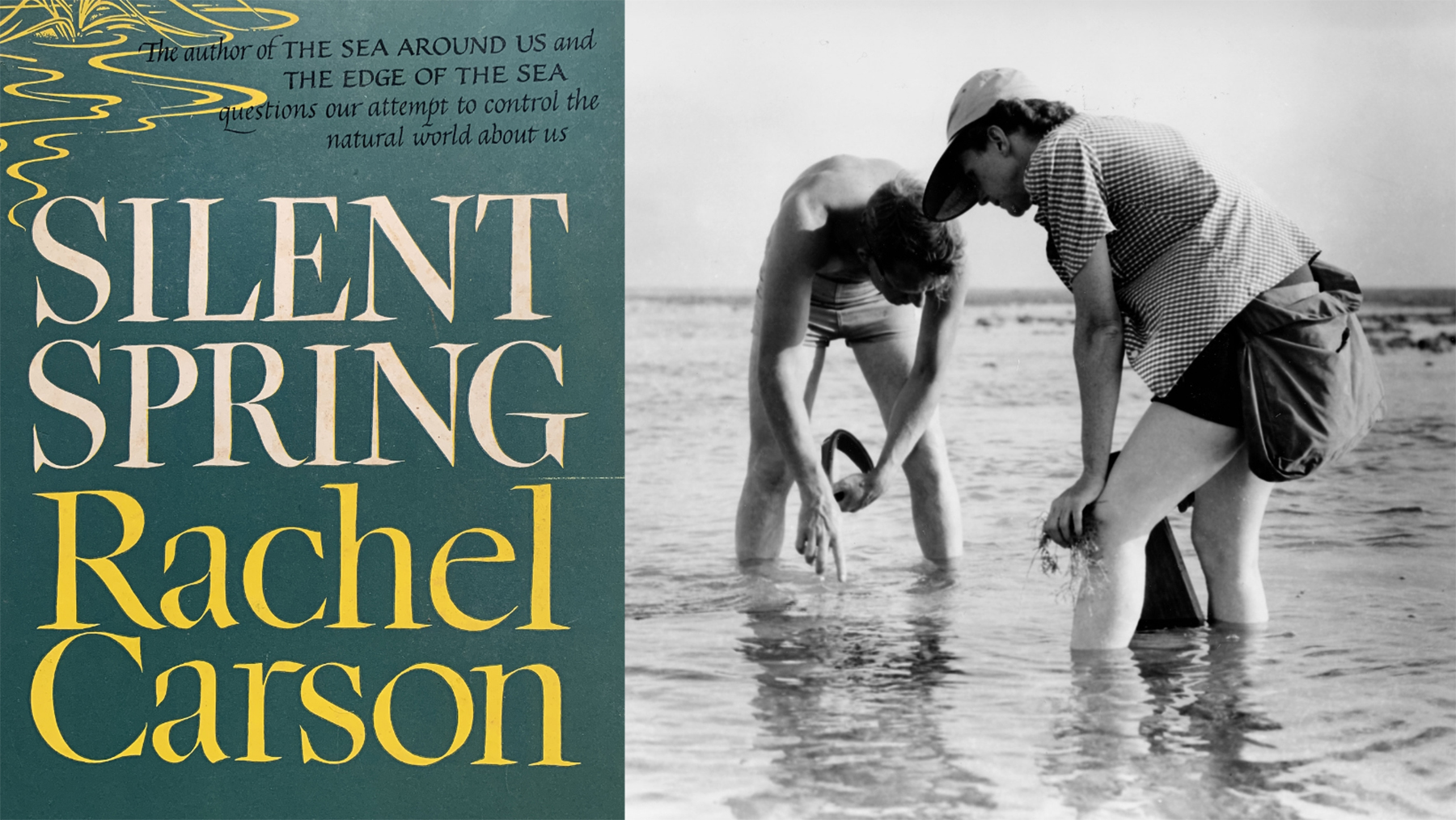

Left: Book cover for Silent Spring, by Rachel Carson. Right: Carson conducts Marine Biology Research with Bob Hines in the Atlantic, 1952, image via Wikimedia Commons.

In 1900, the growing Carson family settled on a hillside north of Springdale, bounded by woods and orchards, in a two-story wood house without indoor plumbing. An avid reader and writer, young Rachel was educated by her mother, and by the surrounding woods and river. Drawn to a conch shell of her mother’s, she became enchanted with the sound of the ocean it mimicked when held to her ear. Rachel studied English and biology at the Pennsylvania College for Women, and in 1928 spent a year with the Atlantic Ocean on a fellowship to Woods Hole, Massachusetts. In 1929, she attended Johns Hopkins University as a graduate student in zoology and genetics.

Carson spent a long career in the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, writing on ocean life and coastal ecosystems for a general audience, making academic and specialist texts accessible to ordinary readers and radio listeners. Outside of government publications, her essays were widely published in newspapers and magazines. Her first book, “Under the Sea Wind,” came out in 1941.

Carson first learned about DDT while at Fish and Wildlife in 1945. Development of the pesticide was compared to the Manhattan Project, and Time magazine called the chemical “the insect bomb.” DDT encountered public opprobrium in 1957, when it — along with fuel oil — was sprayed on homeowners’ properties in Long Island, New York, as part of the federal spongy moth eradication program. Carson followed the Long Islanders’ lawsuit against the United States and began gathering accounts of environmental damage attributable to DDT. Using confidential sources from within the federal government, along with documentation from the Long Island lawsuit, she presented evidence that overuse of pesticides eradicated bird populations in a 1959 letter to the Washington Post, calling the effect the “silencing of birds.”

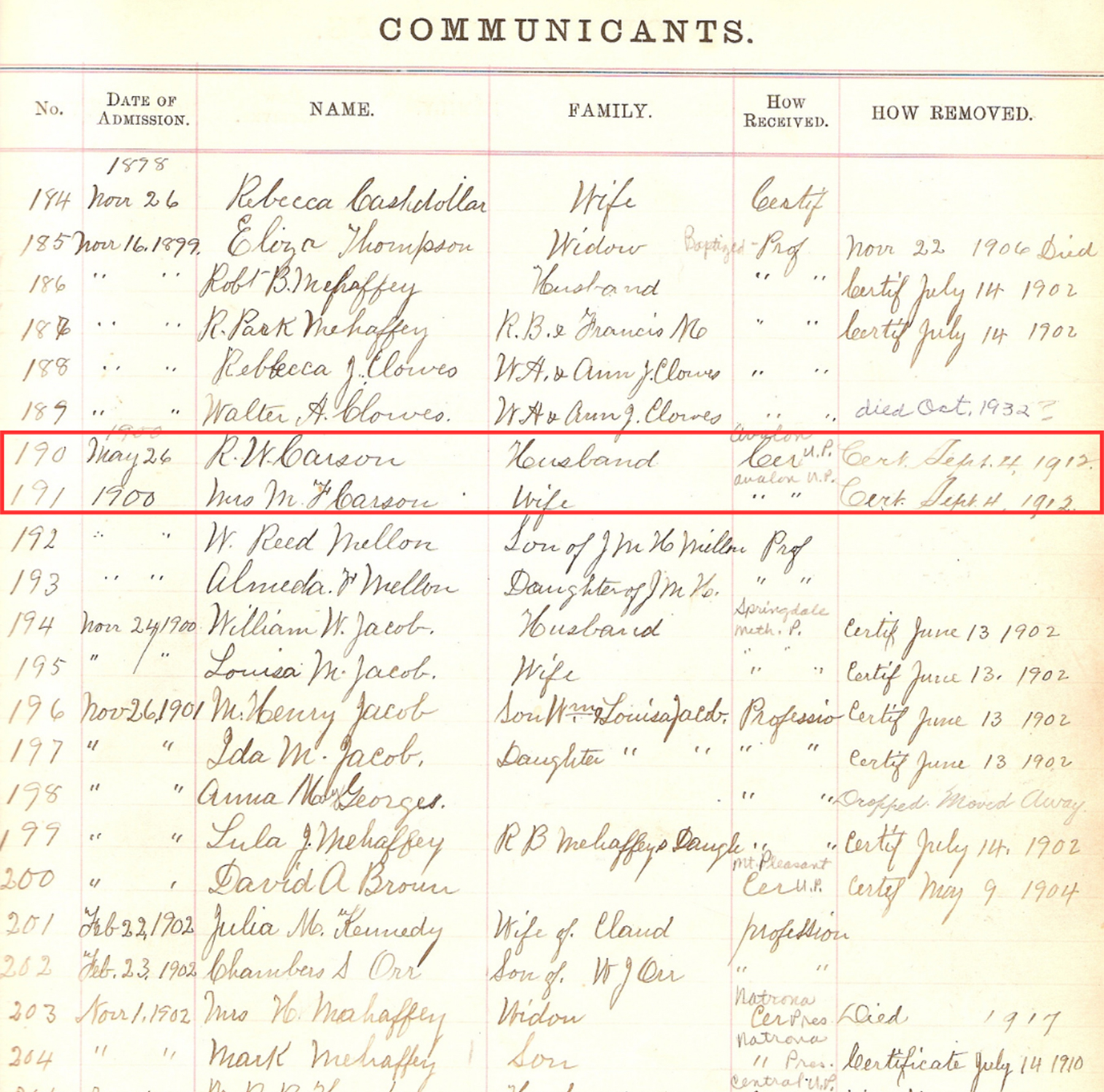

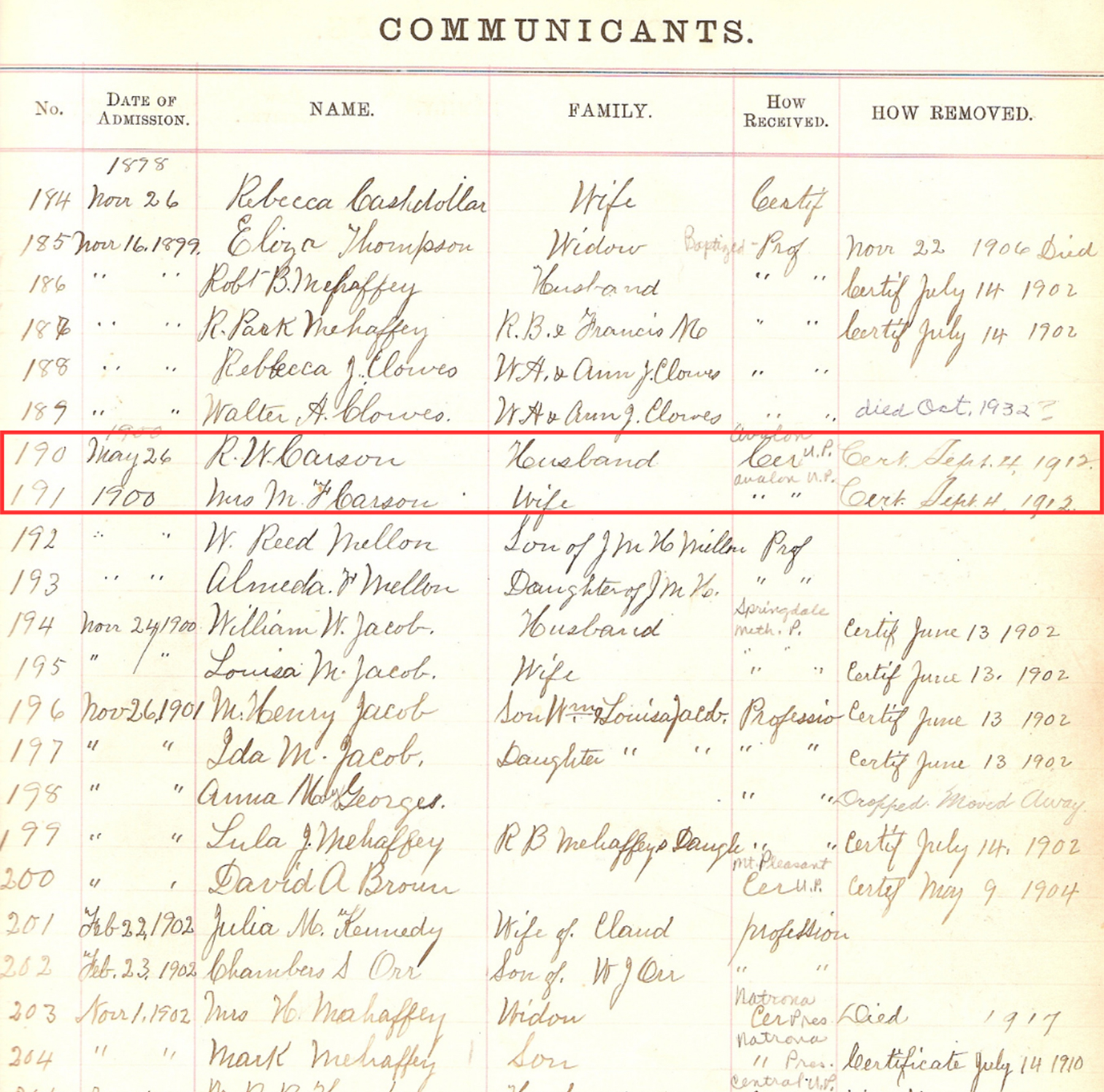

Springdale United Presbyterian Church Communicants via Presbyterian Historical Society records. Robert & Maria Carson’s entry is squared in red.

Springdale United Presbyterian Church Communicants via Presbyterian Historical Society records. Robert & Maria Carson’s entry is squared in red.

“Silent Spring,” released in 1962, argues that pesticides are in Carson’s usage “biocides” — their effects persist far beyond their target and damage whole ecosystems. The book was a commercial success and the rest is history. “Silent Spring” would re-energize the environmental movement in the United States, transforming it from romantic conservationism into a militant defense of ecosystems from human assault. Jimmy Carter would award the Presidential Medal of Freedom to Carson, posthumously, in 1980. Pittsburgh’s old Ninth Street Bridge would be renamed the Rachel Carson Bridge on Earth Day, 2006.

DDT would be banned in the United States in 1972. However, biocide is arguably ongoing. Some Western European studies of insects in the mid-2010s indicated biomass declines over the prior 30 years of as much as 75% — The New York Times called this “The Insect Apocalypse.” While local declines of biomass in dense human populations in Europe and the U.S. are well documented, insect populations in rural parts of the world appear more stable. Scientific consensus is that insects face a combination of human-caused stressors, chiefly “deforestation, climate change, agriculture, introduced species, nitrification” from commercial fertilization and “pollution.”

Carson is not known to have attended church of any kind as an adult, but her belief in nature deserving defense from humanity’s attempts to kill it evokes a kind of secular piety. Ironically, the U.S. chemical industry posthumously treats Carson as a religious fanatic who inspired an environmentalist crusade.

In fairness to her opponents, Carson wrote with lightning, and you can understand why titans of industry would fear her. “Why should we tolerate a diet of weak poisons, a home in insipid surroundings, the noise of motors with just enough relief to prevent insanity?” she asked. “Who would want to live in a world which is just not quite fatal?”

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.