Quilts That Keep You Up at Night

Michael A. Cummings, a seventy-seven-year-old quilt artist based in Harlem, is the only person he knows of who has slept beneath one of his works. “I have put my quilts on my bed when I was cold,” Cummings said the other day. “When I first got to New York, I was putting layers on top of me on the bed, and I couldn’t move, hardly, because it was so heavy. But I was warm.” Eventually, his mother and his sister told him about electric blankets. Over the years, he has made some quilts for friends with babies, but none made it into a crib. “One woman I know, she just put it on the side of the baby bed, and the baby looked at it,” he said.

Cummings’s work typically hangs in galleries, museums, foundations, and embassies—the realm of art. The Whitney has exhibited quilts since 1971; more recently, A$AP Rocky wore a quilted blanket to the Met Gala, and the fashion designer Emily Bode has outfitted Harry Styles and Bad Bunny in quilted garments. Quilting, though, can conjure images of hot-glue guns, pipe cleaners, and old ladies at JOANN stores—the world of crafting. Cummings doesn’t like the classification. “I don’t think it should exist,” he said. “There shouldn’t be a division. It’s all art.”

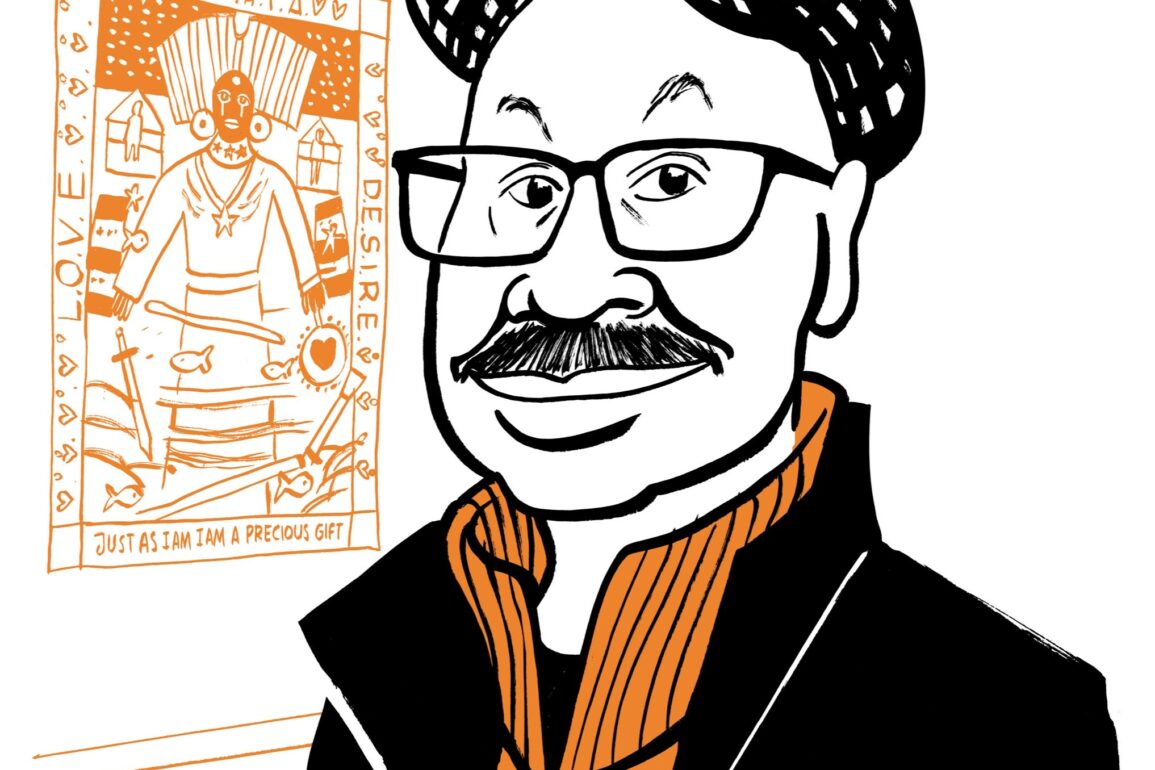

Cummings was standing in the back room of Hunter Dunbar Projects, a gallery in Chelsea that’s putting on his first retrospective, called “Storyteller.” He wore a red quarter-zip sweater and a houndstooth newsboy cap and led a tour of some of the pieces.

Cummings grew up in Los Angeles and moved to New York in 1970. He found work in the city’s Department of Cultural Affairs. One day, he was tasked with making a banner, and, after a tailor wanted a hundred dollars for the job, he decided to teach himself to sew it instead. “I said, Wow, this is better than painting,” he recalled. He soon went to Macy’s and bought his own sewing machine. His work often explores Black history—sometimes in frightening detail—which he eases viewers into with bright colors and embellishments. He stopped in front of a quilt titled “Waiting for Slave Ship Henrietta Marie,” which features four enslaved women in West Africa. “These women here are not having a good time,” he said.

Standing in front of “Yemaya,” a mermaid quilt saturated with sequins and electric blues and pinks, he peered up at the titular Yoruba water goddess. “Your mind might go to a romantic fantasy and ‘Oh, isn’t that nice,’ ” he said, gesturing toward the words “LOVE” and “DESIRE,” which are featured between red hearts. “But ‘Love’ and ‘Desire’ were in the names of slave ships,” he said. When you begin to notice the finer details—bloody palms, corpses, and the Grim Reaper—there’s a shift. “It becomes ‘Oh, it’s not nice.’ ”

Yemaya is sometimes believed to have watched over Africans as they were forced across the Atlantic, and she is still worshipped today. Benjamin Reed Hunter, the co-owner of the gallery, who was accompanying Cummings, said, “I’m not kidding, there was a woman who was just here, in front of ‘Yemaya,’ and she—” He raised his hands above his head, tilted his chin toward the ceiling, sucked in air, and swayed back and forth. Cummings said that at a recent exhibition in Birmingham, England, two other quilts brought women to tears.

Cummings headed for a fabric store nearby, in the garment district, where he gets many of his materials. He doesn’t typically start out searching for anything specific. “You’ll never know what fabric might holler, ‘Take me home, take me home,’ ” he said. The shop resembled a library, but for textiles instead of texts. Rolls of fabric were packed together so tightly that only slivers of each were visible, like the spines of books. Cummings was drawn to a gold cloth with intricate beadwork near the entrance. “I might get a half yard,” he thought aloud, before disappearing down an aisle lined with rolls of fabric as tall as he was.

He wandered toward a collection of African textiles. “The thing I learned about African fabrics is that they have a commercial line that they push,” he said. “If you look at what the actual people are wearing, you don’t see that in the mix of the fabric here.” Cummings once approached a vender at an African market on 116th Street about his clothes. “He said, ‘Well, what do you want to buy?’ I said, ‘I want to buy the shirt that you have on.’ ”

Cummings said that when he’s working he loses track of everything. “You get into a trance. I have a personal trainer with me all the time, and that personal trainer is a sixty-minute clock,” he said, referring to a kitchen timer. “It doesn’t take batteries or anything. And, when that bell goes off”—he snapped his fingers—“it brings me back to reality.” Upon surveying his work, his reaction is sometimes Urkelian. “I step back and ask, ‘Wow, did I do that?’ ”

He took a few laps around the store and scrunched a few fabrics between his fingers—he folds, rather than rolls, his quilts, so he requires material that isn’t prone to wrinkling. But he found his way back to the gold cloth. “Can I see what a half a yard looks like?” he asked the shopkeeper. Looking down at it unfurled, he sighed. “I’ll take a yard,” he said. “See what you made me do?” ♦