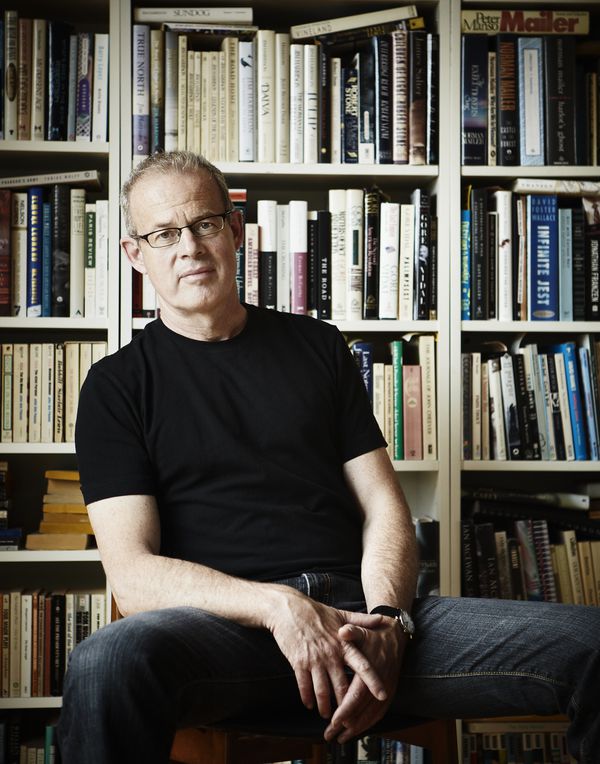

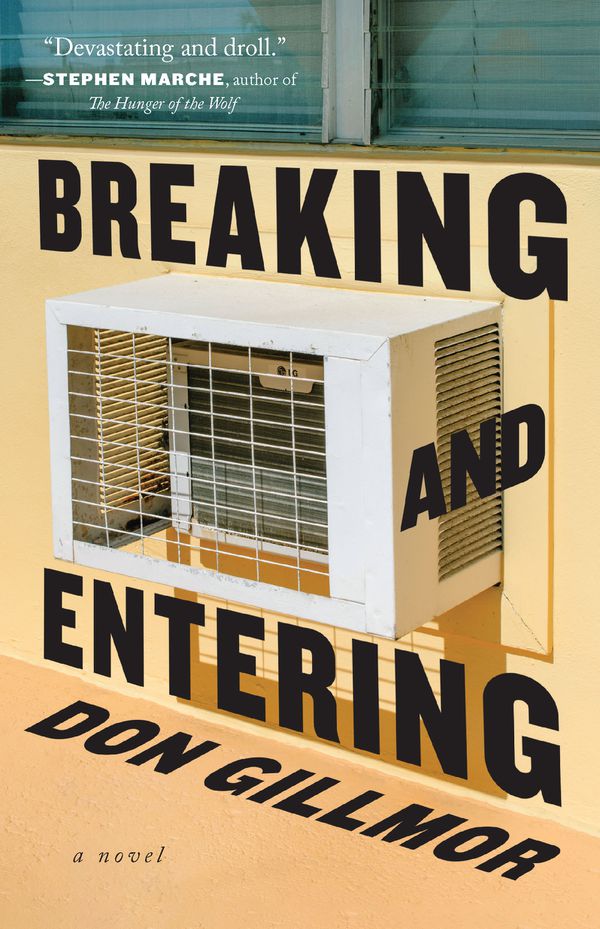

In Breaking and Entering, journalist, Governor-General’s Award-winner, and author of several books Don Gillmor tells the story of Bea, a bored, disaffected, middle-aged art gallery owner.Ryan Szulc/Penguin Random House Canada

- Title: Breaking and Entering

- Author: Don Gillmor

- Genre: Fiction

- Publisher: Biblioasis

- Pages: 240

One of the things that makes a work of literary fiction appealing is its ability to speak to some bit of the human condition. Maybe profound, maybe mundane. But it gets to you. Not every book can do that.

You pick up a Jack Reacher or Harry Bosch novel and you might fly through it, hanging on the last word of each sentence, desperate to find out what happens next. But you never put the book down at the end of a reading session and say to yourself “Wow, that really hits home. I remember the time I had to dispatch half a dozen baddies with nothing but a spork.”

When an author who knows how to both write and think decides to drill down on some bit of life, however, the work hits differently. That doesn’t tend to make a book a page-turner, but it can make it something of an X-ray machine, as if the book is peering inside you. Or maybe it’s a therapist. Either way, it sees through you.

In Breaking and Entering, journalist, Governor-General’s Award-winner, and author of several books Don Gillmor tells the story of Bea, a bored, disaffected, middle-aged art gallery owner caught in a loveless marriage and caring for her ailing mother while surrounded by bored, disaffected, middle-aged friends caught in their own personal iterations of hell.

One day, something clicks in Bea’s head, and she takes up lock picking as a hobby. She even joins a group of lock-picker enthusiasts. She orders a lock-picking set and practises on locks she buys. Soon, she starts breaking into homes – not to steal anything, although she does nab a dress from one home. She does it for the thrill of it. To feel something. To escape.

“This was how it started,” writes Gillmor of Bea’s turn to lock picking. “Sitting in her gallery in deadly June, staring at the sun-bleached desert of west Toronto thinking about how claustrophobic her life had become …” The sentence continues, long, enumerating the many ways Bea is trapped. The sentence ends with “Bea googled ‘escape’.”

Throughout the novel, Gillmor plays with themes, particularly that one – escape. Every character in the book is trapped in one way or another. They’re trapped in bad relationships. In lives they can’t afford. In decaying bodies and minds. One even ends up in jail. Bea’s breaking and entering is a release. It’s an escape. So too are relationships that end. Or at least seem to.

Gillmor succeeds at pulling you into the hopes, dreams, expectations, desires, anxieties and pathologies of his characters. You get caught up in their lives because each of them is a little bit like your life. At the same time, the novel offers a voyeuristic thrill into contemporary existentialist brooding, one that is mirrored by Bea’s exploration – criminal, of course – of the homes and lives of others.

Eventually, Bea recognizes that what she’s doing is, let’s say, problematic. She visits a therapist and tells her about her irregular hobby. “What are you hoping to find, do you think?” the therapist asks Bea. “I’m not sure,” she replies. “What parts of their lives do you see?” the therapist follows up. “The parts they don’t show the world.”

Those “parts they don’t show the world” are the parts we don’t show the world. The ordinary things we all pretend are extraordinary, exclusive to us, as if no one could possibly worry and struggle and suffer like we do. In the homes she breaks into, Bea finds credit card statements indicating heavy debt, medications suggesting that people are fighting just to get through the day, half-empty closets pointing to relationships that are at least as broken as hers and those of her friends.

The novel is set during a prolonged heat wave in Toronto that stretches into the fall. The story dips into and out of the climate crisis, blending it in with all the other anxieties stacked up inside the lives of its characters. Midlife crisis meets the climate crisis. That ought to resonate with some, particularly as Canada faces the latter half of its worst-ever wildfire season and the world reflects on 2023, the hottest year on record.

I’m not betting that Breaking and Entering is going to be made into a feature film any time soon. But it ought to be. It reads like an anti-Under the Tuscan Sun. It reads like broken, twisted reimagining of Eat, Pray, Love. Its pages are suffused with anxiety, and a feeling of suffocating. And yet, like jazz, the moments of tension in the book give away to moments of relief, only to return to building tension once more. To the extent the tension abates, it’s because it ends in decline and breakdown.

Late in the novel, Gillmor surveys the stages of places we live as the stages of our life, a natural real estate arc where we begin in a crappy student apartment, “then a larger space, a starter home, a move to something larger to accommodate the growing family, downsizing after the children moved out, moving to a condo, then a modest apartment in an assisted living residence, and finally a small room in long-term care. We start small and end small.”

He might have added that we tend to end up in an even smaller place – a box or an urn. But maybe that would have been a bit on the nose.

Breaking and Entering is a fitting book for the moment in which we are living, staring down a housing crisis, a health-care crisis, a climate crisis, an affordability crisis, and, no doubt, a crisis or two of our own personal variety. Reading it won’t make you want to emulate Bea, taking up lock picking and breaking into homes. At least, it shouldn’t. But it will strike a chord. It will connect you in one way or another, to one character or another. And it may even bring into focus your own struggles, perhaps in a constructive way – a way that makes you want to do the life work that so many in this novel don’t. No lock picks required.

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.