Who does Hollywood want Black women to be? The ethereal Lena Horne was the star-making institution’s first attempt at calculating a critical answer. According to prominent Black film historian Donald Bogle’s new book, Lena Horne: Goddess Reclaimed, in the limited space of early Tinseltown Black possibility, the high-yella star’s transformation from Cotton Club chorus girl to a once-in-a-generation actress was a bittersweet one. As MGM’s first Black ingenue, Horne was awarded the glamour and press that catapulted her into international stardom. Still, the glamour was no substitute for the career that, although promised, never fully arrived.

My earliest memories of Horne are of her beauty and an air of discontentment around her name. “She was beautiful … but what could’ve been?” was a shared sentiment that echoed in my periphery. Though she fulfilled public expectations of crossing color lines and becoming a credit to our race, what she couldn’t do became the overarching message. History-makers, especially those who have built a second skin from a lifetime of countering stereotypes, are seldom awarded the fullness of their humanity.

Drawing on extensive research, Bogle chronicles the star’s struggles with the quick to be proclaimed icon status that trapped her inside the limited perceptions of being. The inner workings of the soul the star couldn’t bare — due to the injustice of the times — was rarely imagined in the consumable public packaging of her life. From her earliest onscreen persona, Horne navigated being a prototypical symbol of Black sensuality, uplifting figure for Black audiences, and educator of Black plight. With great affection for the star in his third substantial writing on her, Bogle challenges us to consider that Horne is not simply defined by the limitations of what she couldn’t achieve, and that we should look to her continuous reinvention as a sign of resilience in a racist industry.

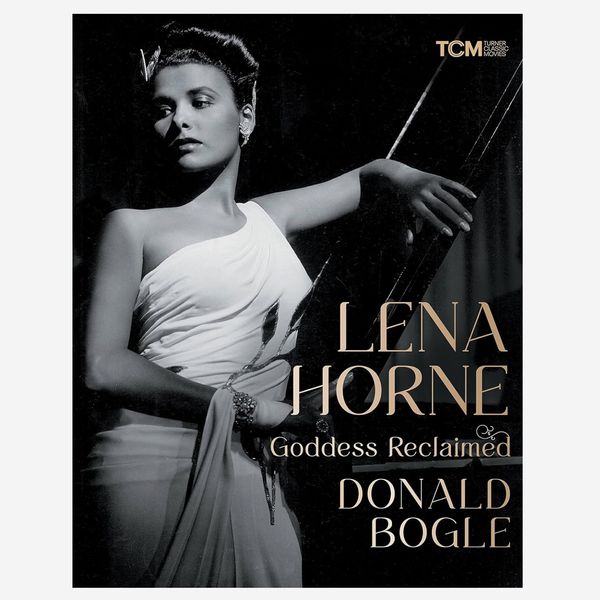

Photo: FPG/Getty Images

Horne’s first brush of simmering fame arrived in the early 1940s at the West Village nightclub Café Society, an integrated watering hole for progressives. There she was first noticed by MGM’s famed composer Roger Edens and made her way to Los Angeles on a dream after a stint in race pictures, Black-cast films for Black audiences. Edens, struck again by Horne’s siren song upon seeing her perform at a Los Angeles club, arranged for her to meet with studio executive Louis B. Mayer. As that meeting went on, Horne learned MGM had purchased the Broadway musical Cabin in the Sky and they were looking for its star. They found a meteorite in Horne, who became the first Black performer to sign a seven-year contract with a major Hollywood studio.

“Lena’s appearance set her at the epicenter of Hollywood’s power elite. Though she herself was not yet a part of that society, it was an acknowledgment that here she belonged,” Bogle writes. With her café-au-lait coloring and alluring features, the subtext of her career swiftly became Can she do anything? and Should she? MGM — which used Horne as a case study for how Black actors should appear on camera through extended hair, makeup, and lighting tests — couldn’t find a solid place for the star outside their own constraints of limiting Black characterization. At the insistence of her father (“Mr. Mayer, it’s a great privilege you’re offering my daughter … [but] I can buy my own daughter her maid,” he told the studio bigwig) and the firm investment of the NAACP, Mayer promised that Horne would set new precedents. Her untouchable beauty became a constant reminder that even though she was welcomed into Hollywood’s golden doors, racism became a hindrance to displaying the fullness of her gifts. She was, as it is often told, a performer whose star ascended “too soon” for the industry’s racism to allow her full shine.

Photo: Silver Screen Collection/Getty Images

In 1917, Lena Mary Calhoun Horne was born into what she describes as one of the “First families of Brooklyn” — members of Brooklyn’s prominent Black bourgeoisie clan who were patrons of Black causes and heralded as model citizens of the race. Residing at the fenced, stately paradise of 189 Chauncey Street for much of her childhood, Horne’s first role model was the lady of the house, her grandmother Cora Horne. The elder Horne was a founding member of the National Association of Colored Women and organized with YWCA’s Red Cross Unit. Along with her paternal grandfather, Edwin Horne, the Hornes were early members of the NAACP. The prominent family rarely discussed slavery and Black conditioning outside of the plush world they inhabited. The soon-to-be star later developed her Black consciousness from her professional peers like the spirited Paul Robeson, who was able to attend Rutgers University on a scholarship sponsored by Cora Horne.

Teddy Horne, Lena’s father, rebelled against the life set up for him and became a Pittsburgh-based gambler after he split with Edna, Lena’s mother, before their daughter was school age. Edna — who longed for a career in show businesses and realized her ambition to make it an industry obsessed with youth withered as she aged — invested hopes deferred in her teen daughter.

It was Edna who convinced the 16-year-old Horne to become a chorus girl at the segregated promised land of the Cotton Club. The starlet, earning 25 dollars a week in the mid-1930s, described the experience as “a form of indentured servitude” and had to dodge the advances of the exclusively white patrons who were looking to settle down with the young “tall, tan, and terrific” girls on the chorus line. Horne’s mother accompanied her, now the family breadwinner after her mother remarried, to the nightly appearances. Edna eventually realized Lena needed to be free of her aggressive Cotton Club contract as the gangster owners attempted to further exploit her youth and beauty for the club’s gain. With the help of the rough and tough acquaintances of her father, Horne was freed. She soon struck out for the greener pastures of New York’s Black nightclubs and was principal vocalist with Noble Sissle’s orchestra before eventually being called to Los Angeles.

Photo: Underwood Archives/Getty Images

In Lena Horne: Goddess Reclaimed, Bogle paints the Brooklyn-born belle’s search for self, structure, and joy as a lifelong one. The starlet’s MGM contract bore speciality music numbers in white-cast films and two pivotal Hollywood Black films, Stormy Weather and Cabin in the Sky (both 1943; she was on loan to 20th Century Fox for Stormy Weather). Cabin in the Sky’s remote world of segregated racial contentment placed the songstress as the light-skinned temptress while Stormy Weather’s wartime fantasy highlighted the best of her vocal and performance gifts despite the underwritten character. To be Hollywood’s Black belle came at the unforgivable price of sexual harassment, racism, and cruelty from executives and peers alike. Restricted for her refusal to be typecast as a maid and a budding interracial romance with a white MGM composer, her sultry voice and onscreen dynamism were underserved by a system fearful of her.

“They didn’t make me into a maid, but they didn’t make me anything else either,” Bogle quoted Horne as saying in his 1973 masterwork, Toms, Coons, Mulattoes, Mammies, and Bucks. “I became a butterfly pinned to a column, singing away in Movieland,” she said.

Photo: Ron Galella, Ltd./Ron Galella Collection via Getty Images

As the butterfly’s wings showed other stars and the industry the path of metamorphosis and dignified image of Black performance, the starlet eventually flew freely performing on the Black club circuit and to a late-life Broadway triumph with her one woman act surveying her illustrious career. Even posthumously, she continues to make history. Just last year, 12 years after her death, a Broadway theater was named in her honor, making her the first Black woman to receive the distinction.

Throughout the history of film, Black women’s cinematic possibility has been distorted and maligned. Horne’s ability to make a way out of no way is one mirrored in today’s Black Hollywood stars — take Viola Davis, who has protested the industry’s insistence that she is the “Black Meryl Streep” despite her pathbreaking career and Oscar win; or Nicole Beharie, whose ascension to superstardom was halted when she was “blacklisted” by the team behind the show that should have made her a household name, for example — as that question of “Who does Hollywood want Black women to be?” contorts and persists. But in a new reading of this dynamic performer’s life, we begin to understand that the only slice of heaven offered to Black women artists is one where they protect, reclaim, and articulate their own story.

Revisiting Lena Horne’s Legacy

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.

Leave a Comment