It’s quiet in the Adidas office. Staff shuffle amongst themselves, having hushed conversations yet alert, waiting for the arrival of hip-hop’s greatest trio, Run-D.M.C.

Large glass windows span the entire length of the concrete room, overlooking Manhattan’s downtown area and into Brooklyn. Everything seems small in comparison, the tall ceiling dwarfing what lay below. But when Darryl McDaniels and Joseph Simmons, surviving members of Run-D.M.C.’s trio, enter with Adidas President Rupert Campbell, the room suddenly feels small. McDaniels’ booming voice fills every corner of space, and it becomes clear we’re all in the presence of history.

By the time their single “Walk This Way” had penetrated white radio stations in 1986, Run-D.M.C. already made a name for themselves. Their first track, “Sucker M.C.’s” had become a hit just a few years prior and put them in the spotlight. McDaniels, Simmons, and Jason Mizell, fresh out of high school, had suddenly reinvigorated rap, which seemingly felt like it had peaked years prior.

“You have to do what’s real,” Simmons told Rolling Stone in a 1986 interview. “It’s like how my ideas come to me, naturally. That’s how I came up with the idea for ‘My Adidas.’ I thought one day of all the incredible things I’ve done with these sneakers on”

Raising Hell, the album which “My Adidas” debuts, catapulted the trio into a worldwide phenomenon. It was the first rap LP to go platinum and would bathe Run-D.M.C. in riches. After garnering over $2 million in sales over a few months (more than $5 million today), the group appeared on Saturday Night Live and The Late Show Starring Joan Rivers. Being thrust into the public eye amplified not only their music but also their style.

Before Run-D.M.C., men’s groups were often seen sporting suits, reflecting the times when business attire encompassed all forms of fashion. “We would tell Russell [Simmons], ‘We ain’t wearing that shit,’” McDaniels retorts as we gather to discuss their come-up in music and the style that resulted. “Our idols were the B-Boys, the break dancers, the graffiti artists, the high school kids we grew up looking at. So we were like, ‘We’ll wear that.’”

In celebration of hip-hop’s 50th anniversary, Rolling Stone sits down with Run-D.M.C., the true architects of the genre, and Campbell to reflect on the past 50 years, the present they find themselves in, and the future of music and style.

When the trio became global, it was the first time you saw a men’s group outside traditional suiting. You platformed casual and streetwear worldwide. Was that intentional?

Joseph Simmons: We just had a smart enough manager to say, “Whatever you got on, wear that to the show.”

Darryl McDaniels: No, it was a little deeper than that.

Anything holy or sacred to a nation, people, or place will get diluted once it’s commercialized. What happened with the first hip-hop groups got into the recording industry, they didn’t stay who they were when they were living in the Bronx. When they got into the music business, there were no rappers to look up to. Who were their idols? The Rolling Stones, Sex Pistols, Rick James, Parliament-Funkadelic.

When we came along, we would tell Russell, “We ain’t wearing that shit.” Our idols were the B-Boys, the break dancers, the graffiti artists, the high school kids we grew up looking at. So we were like, “We’ll wear that.” When Jay came into the group, Jason Mizell our DJ, and DJ Hurricane, the way Run-D.M.C. looked was how Hurricane and Jay went to school. So we said that’s how we’re going to look.

Once album covers started being made, here’s me and Run with the Adidas suits on. You didn’t see a celebrity, you saw yourself, right? That’s what our appeal was—we were relatable. We connected with the streets; we didn’t create it. “We took the beat from the street to put it on TV/My Adidas are seen on the movie screen.” When we did that, the world thought it was new, but we’ve been doing this since ’69.

Where did your love for Adidas start? I heard you mention Pumas were also gaining traction at the time.

Simmons: The streets.

Everything was in the streets. We wanted to be as cool as whatever the newest, coolest thing was we couldn’t afford to wear. Once we made a dollar, we could buy more Adidas. We could buy the gold chain. We could buy everything Jamaica Avenue had to offer that was above our price point before we started making any money.

McDaniels: I got my first pair of Adidas for Christmas, and I set them up when I went to sleep, I waved to them, and I went to bed. I couldn’t wait to wear them.

Simmons: They made you cool.

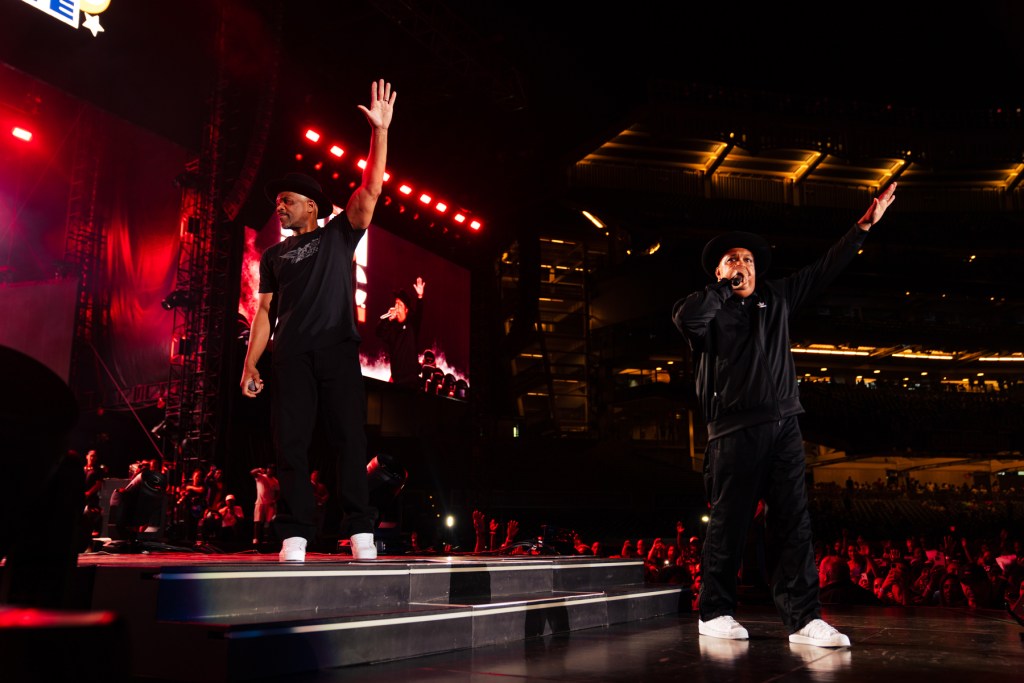

Run-D.M.C. perform at Yankee Stadium for the 50th anniversary of hip-hop.

Adidas/C’est La Zee

Do you remember scuffing your first pair?

Simmons: Hated it. But he was so cool [points to McDaniels]. He knew how to clean sneakers very well, and that’s why Adidas are so important. Pumas, you mess them up, and it’s over. You pour a little ketchup on a pair of suede Pumas, or somebody steps on your foot, and you’re done. You’re done. You’re literally done.

McDaniels: Even the leather would crack; remember, it would get a wrinkle. But these…

Simmons: Indestructible. They’re indestructible. They can be cleaned with…

McDaniels: Soap and water.

I go to all this sneaker convention stuff, and everybody got the booth with the sneaker cleaner. They’ll show me what you do with it, and then in the midst of that, they’ll stop and say, “Get the fuck outta here, D,” because they know I don’t need them. I just need soap and water for my Adidas.

Now, “My Adidas” drops, goes global, and sneaker sales in New York explode. Because of that, the Adidas team comes to one of your early shows…

McDaniels: At the Garden.

Simmons: They saw the craziness and said, “There’s no way we’re not giving you a deal.”

What was running through your mind when you got the deal, though? This was a big moment having young Black rappers as the face of the brand.

Simmons: We didn’t know. We just liked being on MTV. “You got a sneaker endorsement.” What’s that?

You got to understand that you’re coming from Hollis and got very little. Our parents weren’t broke, but we couldn’t get everything we wanted. Once we were hot, somebody said, “You’re on MTV.” What’s that? “You have a sneaker deal?” Okay, that’s another chip book. We were just burning hot. So we couldn’t understand what it meant everything that was coming to us. We weren’t like, “Oh, we got an Adidas deal!”

McDaniels: Cause we were buying them anyway, even when we had the deal.

Simmons: And remember, there were no deals at that time. They didn’t exist…

McDaniels: So it wasn’t something to comprehend.

Simmons: We didn’t know what to think about it.

McDaniels: It’s the word we said on Raising Hell. We said unconceivable, but the word is inconceivable.

Adidas/C’est La Zee

So there was no intention of writing the hit with the hopes of something monetarily coming out of it?

McDaniels: We ain’t talking about something we really don’t appreciate. I don’t care how much money you pay us. I don’t need the hundred million dollars. That’s not real. Hip-hop’s about keeping it real.

Reflecting on the past and now looking at the future of style through music, where do you think it will go from here?

Rupert Campbell: From an Adidas perspective, we have been involved in culture for the last 50 years as a brand. I was having a conversation with somebody just before you arrived to say, what happens is we will push the shoe, and the shoe will blow up. We will cool it off a little bit and push it again, and it’s now just starting to take off again. The black-on-black and the black-on-white are now beginning to take off. So in terms of the culture, shoe, and partnership through the next 50 years, we’ll be sitting here in 50 years talking about the last 50 years that have gone by and what we expect for the next 50 years.

It seems like nowadays, brand endorsements and fashion brands are entwined. Is that part of the formula? Music is a business, afterall.

Campbell: From what I see and how it’s worked throughout the years, this is deeper than just an athletics brand with a hip-hop group. It’s much, much deeper than that. That’s why I think it will continue.

McDaniels: You got to understand what happened with [Grandmaster] Flash and them. Once you get into showbiz, everything’s on the table. You know what I’m saying? I had to scream on people; I’m not fuckin great in hip-hop just because I made cool records. I’m great in hip-hop because I’m a participant and a member of the culture.

We have a constant that’ll never die. I don’t care what Gucci does. I don’t care who comes out. When Adidas had that carnival we performed at, they were giving Pharrell an award, and he said, “All of this is because of y’all,” you know that. He was like, “Come with me.” I said no, this is your moment. He was mad.

Adidas/C’est La Zee

Campbell: I believe if you write a song and try to endorse something you’re not passionate about…

Simmons: It’s not going to have the spirit on it.

Campbell: Yeah, and people can feel that…

Simmons: Feel every piece of fakeness. It’s like me being a Reverend. You’d never guess that I’m not. I put that collar on because that’s what I believe in. And I still am the Rev; that’s my life. People should stand for what they believe.

McDaniels: Many people in hip-hop sell products because they’re in hip-hop, and they can. But do they last?

You want to know a story? It was… When did Jay-Z’s The Blueprint come out?

Campbell: Probably around… 2002, 2001.

McDaniels: All right, so probably like 2003. This was definitely after [Jam Master] Jay passed. Rest in peace.

So I’m on Broadway by Aster Place, and there’s a Footlocker there, and Adidas is on the corner. I go into Adidas, and I got on a blue shirt, and I got on blue jeans, and I got on white-on-white superstars.

They don’t have the blue stripe sneakers in my size—I needed a 13. So, go down to Footlocker. The guy says, “Sorry, DMC, we don’t have your size.” Now, sitting on a pedestal… what’s the sneaker Jay-Z and Nelly wear?

Campbell: Air Force Ones.

McDaniels: Yes. Sitting there spinning in all of its glory, the Air Force Ones with the blue. I put them on and leave my white-on-whites in the store. This is what we do. I walk out, down Broadway, and the bus driver, “Bah bah-bum bum bum.”

“What’s up?” I keep walking until I get to the corner where Russell used to live at. West 4th, where Tower Records used to be. The garbage man, “Bah bah-bum bum bum.” No words, just mouthing, “what the fuck are you wearing?” I walked back to Footlocker and put the Air Force Ones up there. “Give me the white-on-whites back,” and I never put on Nike again. Why? I can’t wear anything else.

With hip-hop, I would say 70% of rappers don’t care about the culture. And I noticed because they say it in their interviews. It’s a business now. With us, it’s something different. What we were doing in Hollis and in the Bronx connected with you. It’s something deeper. What Run-DMC and Adidas did, means something. We did some good commercial marketing and made history, but this is very special. Just like hip-hop is.

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.