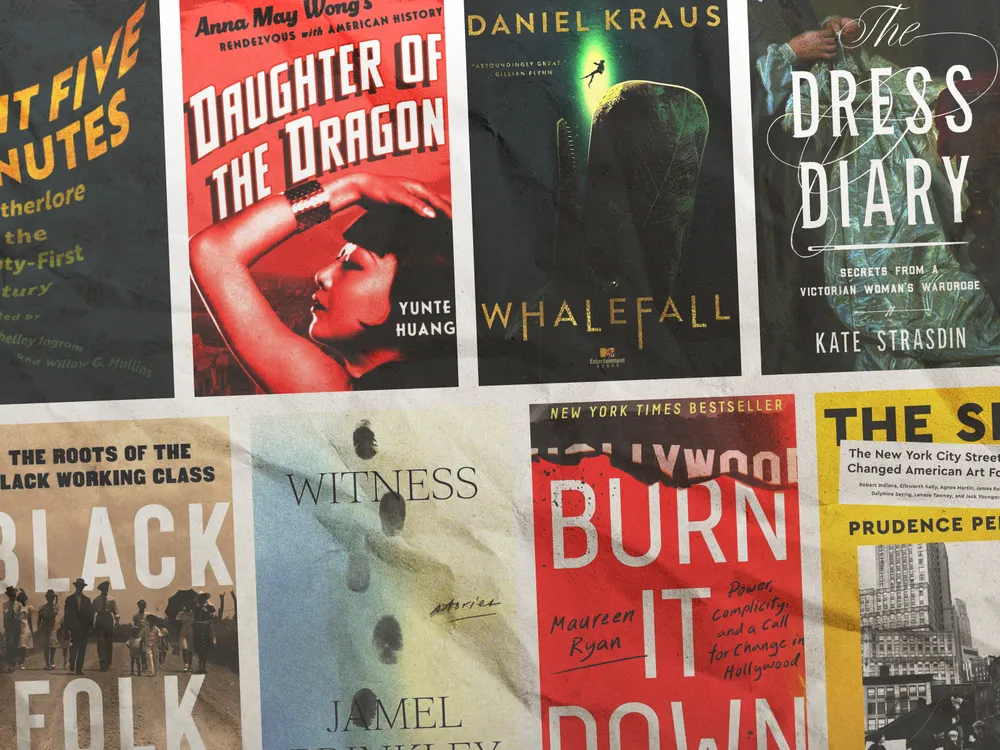

This year’s titles include Daughter of the Dragon, Whalefall and Witness.

Illustration by Emily Lankiewicz

In April this year, Smithsonian scientists in collaboration with NASA launched a revolutionary new tool into space from Florida’s Cape Canaveral Space Force Station. At 7,000 miles per hour, a Falcon 9 two-stage rocket delivered its satellite payload to geostationary orbit, 22,236 miles above the United States, Mexico and Canada. The satellite—a washing machine-sized suite of instruments known as TEMPO, short for Tropospheric Emissions: Monitoring of Pollution—is now providing detailed analysis of the continent’s air pollution. The project has been in development for more than 30 years at the Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

Then, this summer, a female orca that had been found stranded on a Florida beach in January became a prized new Smithsonian specimen: Its putrid carcass was loaded into a small pickup truck and driven north on I-95 toward its new home at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History. Visitors to that museum, meanwhile, were taking in a new long-term exhibition, the first of its kind on a device that has become ubiquitous—the cellphone. Also this year, curators at the National Museum of African American History and Culture made headlines with a fresh take on Afrofuturism and its seismic influences in Black life. And at two of the Smithsonian’s art museums, well-received shows honored the work of video artist John Akomfrah. Other exhibitions included a look at the Disney Parks and a dig into the Chinese ancient city of Anyang, along with shows on contemporary artists like the Japanese-born Ay-O and the Native artists Shelley Niro and Robert Houle, as well as the vibrant works inspired by nature created by the former teacher and Washington, D.C. artist Alma Thomas.

Informing this extraordinary work is a cast of thousands—Smithsonian staffers bringing their best game to the work of preserving specimens and collecting artifacts, launching scientific discovery, and bringing curatorial reconsideration to our nation’s complex history. At the invitation of Smithsonian magazine, 12 representatives make recommendations of stellar 2023 novels, biographies, story collections and journalistic reporting across a range of topics including mid-20th-century Hollywood, life in a New York City art colony, weather-related folk wisdom and what it takes to survive being swallowed by a whale.

Daughter of the Dragon: Anna May Wong’s Rendezvous with American History by Yunte Huang

Recommended by Ryan Lintelman, curator of entertainment, National Museum of American History

The captivating, beautiful Anna May Wong overcame adversity and prejudice in the early to mid-20th century to build a remarkable career as the first Chinese American movie star. But when she began losing glamorous parts to white actresses and found herself increasingly typecast in racist roles, Wong left Hollywood, disillusioned and mostly forgotten. Scholar Yunte Huang from the University of California, Santa Barbara, skillfully recovers the actor’s fascinating story. While fleshing out the missing details of Wong’s life and times, Huang explores the historical, social and cultural context with an English professor’s attention to words, symbols and the meanings behind them. And from this book, a picture immerges of a cosmopolitan, well-connected woman who persevered, finding opportunities to work in Europe and in television before her untimely death in 1961 at the age of 56. Wong is an Asian American icon only now earning the recognition and praise she so long deserved.

Whalefall by Daniel Kraus

Recommended by Nick Pyenson, curator of fossil marine mammals, National Museum of Natural History

How would it feel to be swallowed by a whale? Not just nibbled, like a lobster diver or a kayaker, but full Jonah? The science fiction and fantasy novelist Daniel Kraus imagines a modern riff, pitting a teenage boy against (and inside) an old, bull sperm whale off Monterey Bay. Kraus locates much of the teen’s ordeal in the whale’s multi-chambered stomach, with heavy pours of father-son angst. Impressively, Kraus defies incredulity by doing his homework. I study whales and, as a scientist, I appreciated that all of the pieces of Kraus’ griping narrative fit together from the anatomy of these awesome creatures. Much of the story feels like John Steinbeck’s Cannery Row meets the Red Planet in Andy Weir’s The Martian, paced to the tense countdown of the dwindling air in the teen’s scuba tank. The recently announced movie should be wild—and not for the squeamish.

Whalefall: A Novel

The Martian meets 127 Hours in this “powerfully humane” (Owen King, New York Times bestselling author) and scientifically accurate thriller about a scuba diver who’s been swallowed by an eighty-foot, sixty-ton sperm whale and has only one hour to escape before his oxygen runs out.

The Slip: The New York City Street That Changed American Art Forever by Prudence Peiffer

Recommended by Stephanie Stebich, director, Smithsonian American Art Museum

Several prominent art personalities—from Agnes Martin to Ellsworth Kelly, and from James Rosenquist to Lenore Tawney, not to mention the intense character of New York City itself—abound in this artful story about a specific spot and moment in American art. In the mid-20th century, Coenties Slip, located in the financial district of lower Manhattan, began to attract artists who sought the energy and “collective solitude” of the new art capital. That concept describes both the need for creative quiet and the convening of like spirits. That power of place is also important for artists who came from afar to develop different artistic styles and personal relationships. The history of this unique place is well described from its early shipping days to its heady redevelopment into a vibrant artist colony in the years between 1956 and 1964. For those who love the history of New York City and an insider’s view of the early life of major figures in modern art, this is a compelling read.

Black Folk: The Roots of the Black Working Class by Blair L.M. Kelley

Recommended by William Pretzer, supervisory curator for history, National Museum of African American History and Culture

Inspired in part by the civil rights movement, American scholars of the 1960s and ’70s began to take seriously the notion of social class and the history of marginalized peoples in the U.S., an approach labeled “history from the bottom up.” Research into the social and cultural experiences of workers, immigrant groups and enslaved people led the way, soon to be followed by family, women’s and cultural history. In this well-crafted narrative, Kelley’s own family history spanning 200 years becomes a lens on the development of a Black working class. As good historians do, Kelley raises more questions than she answers about the creation of the Black working class. Those who follow in her footsteps, however, will find Black Folk an excellent guide for examining in greater detail (and thus more diversity) the intersections of family, gender, race, work, class and social justice.

Crossings: How Road Ecology Is Shaping the Future of Our Planet by Ben Goldfarb

Recommended by Jeffrey K. Stine, curator for environmental history, National Museum of American History

Why did the chicken cross the road? Environmental journalist Ben Goldfarb questions the logic of that old riddle, which, he says, treats the road as immutable while demanding an explanation and rationalization for the fowl’s actions. With wit and a wealth of detail, Goldfarb explores the multitude of hazards that the world’s 40 million miles of roads impose upon wildlife and the growing efforts to lessen or mitigate those effects. His discussion of road ecology—a relatively new branch of conservation biology—could hardly be timelier. Highway mileage is projected to double by midcentury, yet biodiversity loss continues at a rate faster than at any time in human history. Without pulling punches in his assessment of highway impacts, Goldfarb laces the book with examples of hope, showcasing how purpose-built infrastructure, such as wildlife tunnels and bridges, redesigned culverts and rewilding roadsides, can blunt some ecological problems, benefiting all inhabitants of the world, both human and nonhuman.

Witness by Jamel Brinkley

Recommended by Lindsay Harris, head of the Research and Scholars Center, Smithsonian American Art Museum

The highly visual narratives crafted by the award-winning short-story writer Jamel Brinkley remind us of the range of perspectives that coexist at any given time, and the importance of storytelling to make sense of the world and our place in it. In his newest collection of ten stories, Brinkley portrays contemporary New York City in the throes of change. A widow, soon to retire from delivering room service in a Queens hotel, finds joy exchanging hand-written missives with the delivery woman from her favorite food app. A young man attending a dance party at the Brooklyn Museum unexpectedly meets his estranged father’s former lover. A group of friends in Bedford-Stuyvesant struggles to recall the business that once operated in a local storefront, which now shelters animals and a troubled, homeless man they barely recognize from their childhood. Throughout the vignettes, photographs recur as portals to the past that offer glimpses of characters and their surroundings as they once were. The story collection highlights how revelatory it can be to formulate and express point of view by integrating the arts.

Witness

In these ten stories, each set in the changing landscapes of contemporary New York City, a range of characters―from children to grandmothers to ghosts―live through the responsibility of perceiving and the moral challenge of speaking up or taking action.

The Dress Diary: Secrets from a Victorian Woman’s Wardrobe by Kate Strasdin

Recommended by Jocelyn Knauf, docent program manager, National Museum of American History

As a museum educator and former archaeologist, I am fascinated by how the seemingly insignificant things that people used and discarded in past eras can give us insight into their lives and experiences. In 1838, an Englishwoman named Anne Sykes began to document in a bound volume the clothing that she and her friends and family wore, including pieces of printed fabrics and swatches of silk. Nearly 200 years later, after in-depth study of what has become known as “The Dress Diary,” fashion historian Kate Strasdin shows us how Sykes’ wardrobe and the garments worn by those around her are tied to broader cultural landscapes and connected to larger social networks, industry and empire. Clothing chronicles the everyday lives of women; the rituals of mourning, the move to a new home, weddings and christenings are rendered meaningful and consequential. But the author also contextualizes this period of the 19th century, tracing the elements of women’s clothing from the cotton plantations in the southern U.S. to the far reaches of the British colonial empire.

King: A Life by Jonathan Eig

Recommended by Chris Wilson, director of Experience Design and the African American History Program, National Museum of American History

In remembering the civil rights movement, we are often blinded by our tendency to understand this period as the consequences of the actions of super-heroic leaders—who are usually men. There is no better example of this than how we remember Martin Luther King Jr. The Black freedom struggle of the 1950s and ’60s is often seen as being defined by King, and King, in turn, is seen as being defined by his public life and work. One antidote to this simplistic understanding is to broaden one’s consideration and see the movement as the far-reaching efforts of the many. In reality, a vast number of people and groups worked to redefine the nation from many directions and through many, sometimes competing, tactics. To deepen our knowledge, we need to fully understand these people along with their weaknesses, fears, flaws and lives beyond the public spheres of their activist work.

In his King biography, which the New York Times calls the “first comprehensive account of the civil rights icon in decades,” Eig helps us see the complexity. We learn the difficult relationship King had with his father and other leaders, his struggles with mental health, and his discomfort with conflict. We learn about those who had as much to do with the successes of the movement but who continue to receive little credit, including women like his own wife, Coretta Scott King, as well as Rosa Parks, Ella Baker and Diane Nash. To better understand this world icon, we should—as Eig does—explore his full life to more fully grasp the movement and our nation’s history.

King: A Life

In this landmark biography, Jonathan Eig gives us an MLK for our times: a deep thinker, a brilliant strategist, and a committed radical who led one of history’s greatest movements, and whose demands for racial and economic justice remain as urgent today as they were in his lifetime.

Wait Five Minutes: Weatherlore in the Twenty-First Century edited by Shelley Ingram and Willow G. Mullins

Recommended by James Deutsch, curator of folklife and popular culture, Smithsonian Center for Folklife and Cultural Heritage

Folk wisdom about the weather, known to folklorists as “weatherlore,” dates to the earliest humans, whose lives often depended on the vagaries of snow, rain, heat and gloom of night—to borrow the folkloric motto of the U.S. Postal Service. The 15 essays in this volume, written by specialists in communications, folklore, literature, philosophy, religion, science and other fields of study, evenly divide into sections on belief, text and tradition. Specific topics include the personal narratives of storm survivors, the contemporary usage of the word “snowflake,” the roles of magic and prophecy in weather prognostication, the effects of climate change on Christian belief, and the difficulties climate change is bringing to home canning. My contribution, titled “Bob Dylan’s Windlore,” derives from my all-time favorite song lyric espousing weather wisdom—“You don’t need a weatherman to know which way the wind blows” from the legendary poet’s 1965 anthem “Subterranean Homesick Blues.”

Burn It Down: Power, Complicity and a Call for Change in Hollywood by Maureen Ryan

Recommended by Elisabeth Kilday, visitor services manager, National Portrait Gallery and Smithsonian American Art Museum

The critic and reporter Maureen Ryan has been writing about entertainment for years and, in her new bestseller, she looks at the widespread sexual harassment and misconduct in the television industry. Through interviews with actors, writers and others in the industry, Ryan doggedly pursues the question of why, after the much-vaunted #MeToo campaign, bad antics and toxic abuses continue behind the scenes at popular television shows. Harvey Weinstein may be behind bars, but the industry allows other abusers to continue working. It was difficult at times to read about shows that I enjoyed in the past, but Ryan doesn’t just highlight the problems—she offers ideas for improvements going forward. Hollywood is not alone in facing these issues of harassment and biases, and readers may be surprised at how they can relate to the stories told and the proposed solutions.

Burn It Down: Power, Complicity, and a Call for Change in Hollywood

In this spectacular, newsmaking exposé that has the entertainment industry abuzz and on its heels, Vanity Fair‘s Maureen Ryan blows the lid off patterns of harassment and bias in Hollywood, the grassroots reforms under way, and the labor and activist revolutions that recent scandals have ignited.

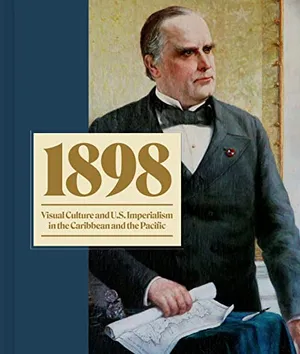

1898: Visual Culture and U.S. Imperialism in the Caribbean and the Pacific by Kate Clarke Lemay and Taína Caragol

Recommended by Theodore Gonzalves, curator of culture and the arts, National Museum of American History

Caragol and Lemay have accomplished an incredible feat—they curated a thoughtful exhibition and edited an accompanying text that links a sorrowful past with the urgency of the present. During the War of 1898, commentators and scholars asked the question about the U.S.: “Are we an empire or a republic?” To dispossess people of their land, seize it for themselves, administer the transfer of treasure and labor across borders, brutally suppress movements for self-government, and feed media with one-sided narratives—all of those and more were the hallmarks of an empire coming into view. Caragol and Lemay highlight perspectives from communities deeply affected by these events in Hawaiʻi, Guam, the Philippines, Cuba and Puerto Rico. Full disclosure: For the catalog, I wrote a short essay about the cost of forgetting empire as well as remembering acts of resistance in the Pacific. If you are not able to visit the show, which remains on view through February 25, 2024, and which the Washington Post referred to as the “best and most engaging work the National Portrait Gallery has done in a decade,” then turn to this accompanying text for the finely crafted context it offers of distant events that today continue to offer us powerful lessons.

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

Recommended Videos

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.