The Artist Making Wellness Culture Look a Little Sick

Few art shows begin with spa music. You can imagine my confusion when I knocked on the door of the Candice Madey gallery, in New York, and heard celestial stomach growls coming from inside. Was this the right floor? The right building, even? Yes and yes, but, in my defense, galleries and spas have more in common than the proprietors of either would like to admit. Both aspire to semi-spiritual experiences, packaged in clean, well-lit spaces with a barely repressed grossness. Both may be regular old businesses, once your eyes adjust to the glow.

The clean, the gross, the spiritual, and the mercantile: these are the key ingredients for Ilana Harris-Babou, the thirty-two-year-old artist whose work awaits you at “Needy Machines,” behind the gallery door. Mix them together and you get a sugary confection known as “wellness,” which happens to be her subject. At this show, you will find, in addition to the spa soundtrack, ceramic pill bottles, a mirror that flashes laboratory invoices, and rectangles of shiny white tile enlivened by colorful fruit. In the past, Harris-Babou’s videos and sculptures have announced their themes with yoni eggs, rose-quartz face rollers, and the like. There’s less of this kind of signposting in the new show, and a few of the best pieces have none at all, as though she were weaning us off the whats of her subject and moving on to the whys.

Harris-Babou was born in Brooklyn, to a mother raised mainly in New York and Connecticut and a father who emigrated from Senegal. She received her M.F.A. from Columbia in 2016; three years later, her art appeared in the Whitney Biennial, and a year after that she made a splash, or at least a respectable spritz, with a show at Hesse Flatow. Much of her work follows the same pattern: First, choose some form of trendy life-style media (HGTV or cooking shows, makeup tutorials) that tells viewers how to be true to themselves while showing off for the neighbors. Then mimic the format—twinkly music, chirpily domineering host, rainbow colors against crisp white backgrounds—while dialling up the contradictions. The centerpiece of the Hesse Flatow show was a short video called “Decision Fatigue,” in which Harris-Babou’s mother walks us through her beauty routine: moisturizing her face with Cheeto crumbs, slurping Pepsi, showing off her chocolate-chip soap. Pretty amusing, but let’s be frank: when you shoot at an industry whose most famous company is called Goop, you can’t miss.

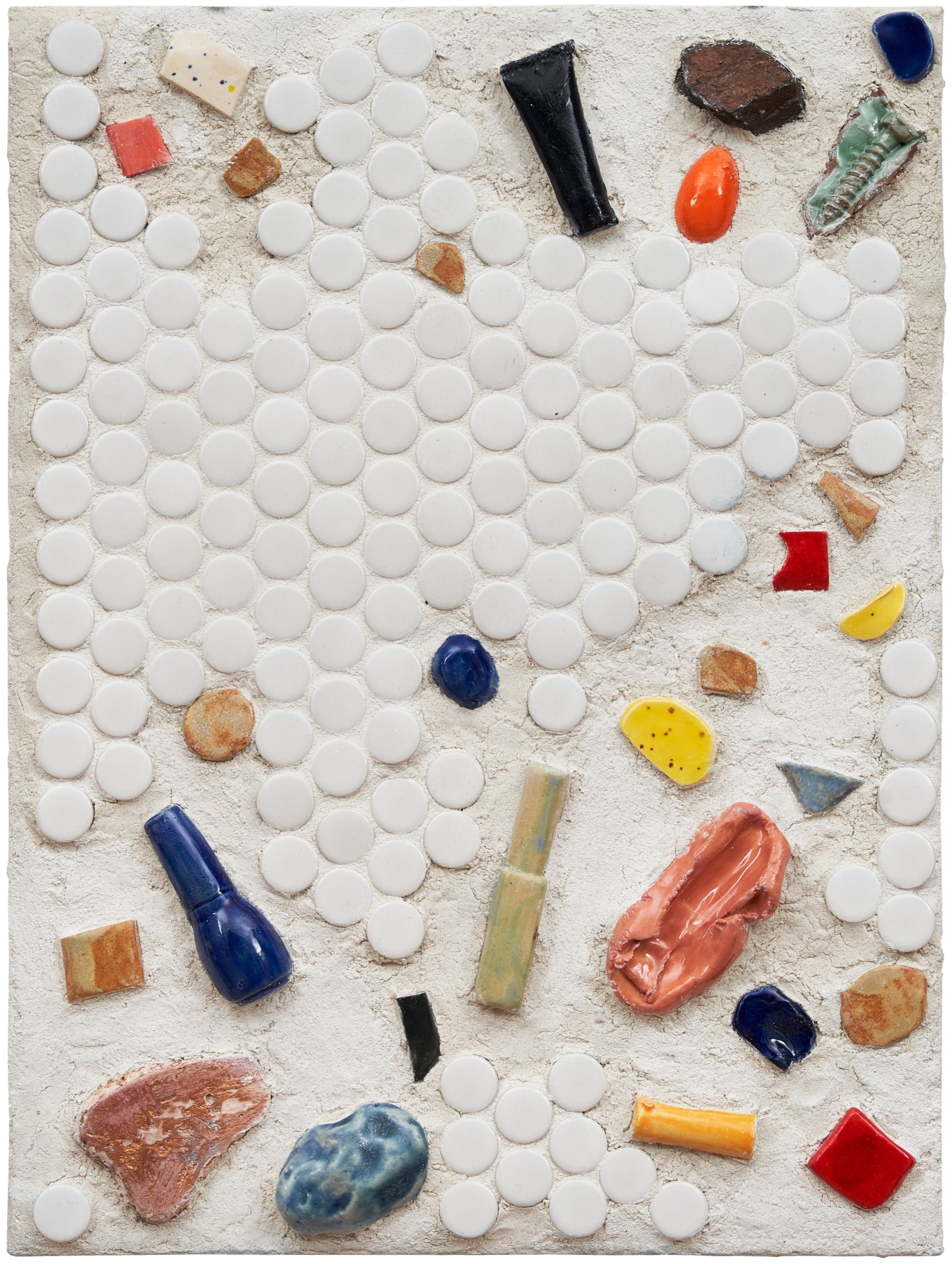

The tile pieces in “Needy Machines” are trying for something harder: not a straight homage to their subject but not an obvious parody, either. They’re basically high-relief sculptures, the size and shape of a medicine-cabinet mirror; even at a glance they suggest a luxury bathroom, ground zero as far as wellness culture goes. The densest one, “Confetti 2” (2023), is as cluttered with bright lumpy shapes as the wall of a rock-climbing gym, though it’s still mainly pale tile and grout. For every wellness object in the show, there is some free-associative pun-object: for the ceramic screw-top bottle of nail polish in “Confetti 2,” a cast of an actual screw; for an ear of corn, a glazed blob that resembles a human ear. The tone is lightly ironic but never sardonic, as though to acknowledge that wellness is a trillion-dollar industry partly because, at its core, it makes a reasonable point. (Is anyone actually against being well in body and mind?)

It is easy to respect these sculptures’ careful, subtle twists on careful, subtle contemporary design, and harder to relish them. Luckily, they’re only a warmup for the real fun. The spa noises turn out to come from “Needy Machine” (2023), a video piece presented on a reflective screen. Over four or so minutes, a series of medical documents jolt cartoon-quick from right to center and, after lingering nowhere near long enough to be read, exit left. Everything is written in an obscure dialect of bureaucratese that all Americans understand, because it only ever means one thing: You are too stupid to monitor your own health, so you need us to do it for you. If you find yourself overwhelmed by all this, you can look at the bottom of the screen and console yourself with slogans like “It’s a part of your life, but it doesn’t define you.”

“Needy Machine” is also a mirror, of course—its video effects never come close to filling the screen—but everything it reflects gets dirtied by the images whooshing by. One moment, you’re frowning over a glossary of medical terms (the more bureaucracy tries to explain itself, the more inexplicable it becomes); the next, the glossary is gone and you’re left giving yourself the stink eye, as though your body is an annoyance in need of fixing. It’s a wonderful prank, reminiscent of glass-covered Francis Bacon paintings that trick you into wincing at a hideous Pope in a box, only to reflect your own body standing beside him. The difference is that Harris-Babou is funny, and not in the polite, sniff-through-the-nose way—“Needy Machine” gets genuine laughs, the queasy kind that come when nothing else can be done.

There’s the way you look at yourself, and then there’s the way you look at your stats-and-numbers self: your weight, your blood pressure, your levels, not to mention the itemized bills for calculating each. Do too much of the second kind of looking and the first is never the same. Wellness culture tries to correct for health care’s inhumanity with green juice and self-affirmation, but in some ways it’s built a prettier version of the same prison: you’re more than a number, fine, but you’re still a product, and your purpose is to fuss over yourself with the help of other products. I’d say this is more or less what’s going on in “Foaming Mouth 1” (2023). It’s not the first Harris-Babou video piece to feature bubbles: in “Decision Fatigue,” they brought you the squelchy side of reality that life-style media try to ignore; in “Liquid Gold,” recently screened in Times Square, the political nuances of breast-feeding. Here they slide down a mirrored screen, blushing with violet light and suggesting the glittery world of wellness goods. If you can forget about the title, it’s quite calming to behold (meditative, cleansing, etc.), until you catch yourself looking. The setup is the same as in “Needy Machine” but the punch line is nastier: the more you try to get lost in meditation, the more of a narcissist you become.

“Foaming Mouth 1” doesn’t address wellness so much as the deeper problem that it fails to solve. That problem? Just mankind’s search for authenticity, as blundering today as it was centuries ago. The art historian Michael Fried devoted some of the most fascinating pages of “Absorption and Theatricality,” his influential study of eighteenth-century French painting, to Jean-Siméon Chardin’s “Soap Bubbles,” which shows a youth engrossed in the quivery orb on the end of a straw. As other scholars have noted, images like this one coincided with a growing distaste for fake, look-at-me bourgeois society; there was a hunger for good, plain people absorbed in plain, unshowy things, inviting viewers to forget themselves, too. It didn’t work out. French absorption painting came to seem as phony as the bourgeoisie itself, another product offering bottled AuthenticityTM. Of which “Foaming Mouth 1” is both example and parody. You can buy the products, you can practice the techniques, you can believe that by doing all this you’ve achieved inner peace, but in the end absorption, warped by the same market pressures it wants to escape, becomes just another kind of theatricality. Today’s private spiritual questing is tomorrow’s preening.

And yet Harris-Babou respects you for trying. She tries, too; in more than a few interviews, she’s said that she makes art about wellness because she’s enamored, not just skeptical, of it. As far as her art goes, that’s for the best. She’s too interested in her subject to settle for cheap shots, and maybe wellness culture deserves the quixotic dignity she grants it. We’ve been hurting for a very long time, after all, and the rose-quartz face roller is just another thing that we’ve invented—including, it would seem, modern painting—in the hope of easing the pain. ♦

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.