Journalist Sowmya Krishnamurthy has spent a large part of her career documenting hip-hop culture. Over the course of her writing career, she’s written pieces for XXL, TIME, Complex and countless other publications. For her non-fiction debut, she was inspired to speak with the savants, the unsung heroes, stylists, and the non-household names that are responsible for rap’s relationship with fashion. This idea sparked following a piece she’d written for XXL. Fashion Killa: How Hip Hop Revolutionized High Fashion is a dissection of the symbiotic partnership between hip hop and style-–it details interesting and imperative moments that were influential such as the beginning and the disappointing demise of Dapper Dan’s original Harlem atelier.

To Krishnamurthy, Fashion Killa provides an opportunity for her to explore how with grit, lyrical prowess, and sartorial inclinations, individuals like Lil’ Kim, Foxy Brown and Kanye West pushed down barriers to create a path for themselves in fashion. Others such as Diddy, Dapper Dan, Kimora Lee Simmons, and Virgil Abloh also receive their flowers—their journeys are highlighted in a unique manner that feels compelling, rather than stuffy. Krishnamurthy describes things from a bird’s-eye view but also injects the book with a bit of her own personal storytelling, by doing so she willingly offers up how she transformed from a hip hop superfan to an intern and later, a journalist in the lauded space.

“When I was putting together the [book], it was really important for me to tell this story in a way that really showcased its integrity and its importance,” the author said on a Zoom call. “I felt it would just be a great contribution to hip-hop as a whole,” she added. To keep the book interesting, she details the start of hip hop in 1973 and its roots in The Bronx, Harlem, and other regions such as the South. She tells me that she wanted Fashion Killa to come out this year in homage to rap’s 50-year history. Krishnamurthy expresses that she feels by celebrating the anniversary of hip-hop in this manner that fans and outsiders will learn so much about the genre.

By utilizing oral history combined with cultural storytelling Fashion Killa pays tribute to key figures within music. It accurately depicts disappointing moments but also the million-dollar moments that have laid the foundation for current artists. Since image-making has always been a part of the industry, it’s glaringly pivotal that this examination accurately portrays pioneering stars, brands, and more. “I really think it’s important to showcase that this is very much an interconnected web and there were so many people involved in making some of these incredible fashion moments happen,” she said.

We recently caught up with Krishnamurthy to discuss key chapters in Fashion Killa, her thoughts on the current era of image-making, and why women like Lil’ Kim and Kimora Lee Simmons deserve more.

ESSENCE.com: Where did the idea for this expansive book on hip hop’s relationship with fashion stem from?

Sowmya Krishnamurthy: So for me, the genesis of the [book] came from a piece I’d done for XXL some years earlier, and as I was doing research for that, I was really surprised that there was no definitive book on the subject. I just kept that in the back of my mind. And then fast-forward when I was really thinking about what I wanted for my first book project, it was really important for me to tell hip-hop stories that are important, stories that need to be told, and to do it in this very sort of elevated lens.

What is your favorite hip hop fashion moment ever?

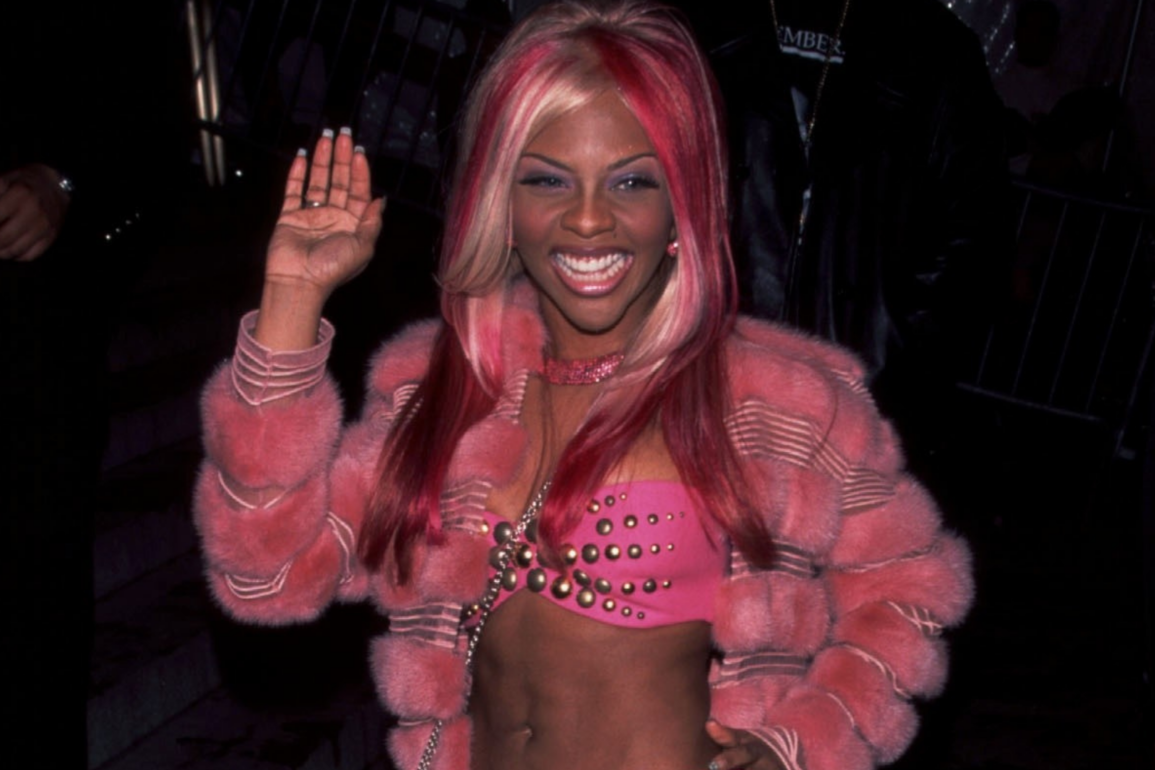

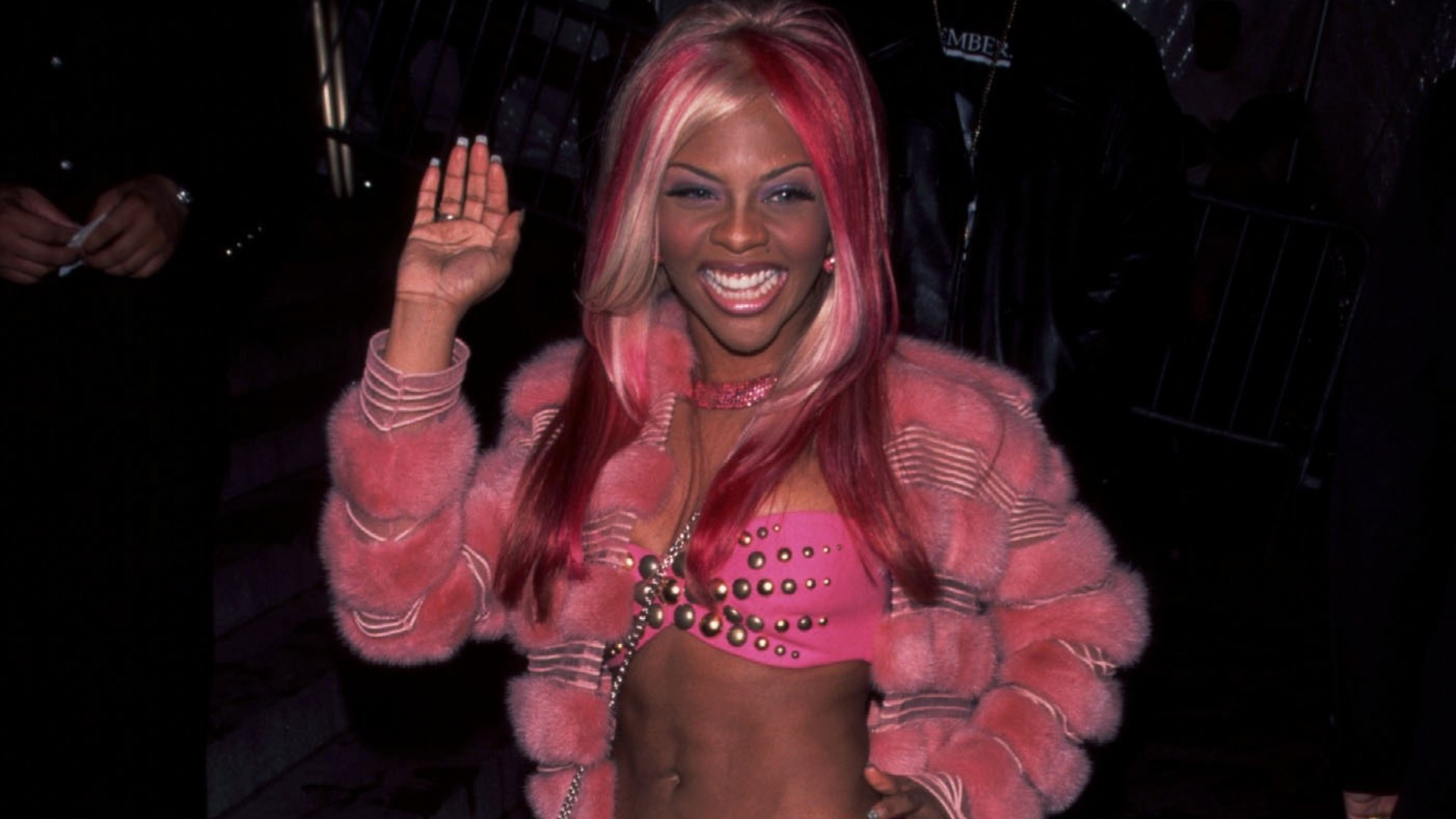

I think one of the ones that just has stayed in my mind ever since I was a kid was Lil’ Kim walking the VMA red carpet in that famous Misa Hylton ensemble. And that was the one where one breast was exposed and it was this almost like a sparkly mermaid pantsuit. And what I found really interesting as I was researching it for my book was that Misa actually used Indian bridal fabrics to put that together, which now when I look closely I can see the outline of peacocks and things that are very much part of something that an Indian bride would wear.

What are your thoughts on the current era of hip-hop and fashion? I’m curious about this idea of artists being aware of the value that comes with packaging themselves.

For a new artist paying special attention to aesthetics and style, it’s really at the forefront. I would even argue a lot of artists have the drip together before they even have [their] first hit record, and that’s very different from previous generations. A lot of that has to do with the fact that we’re in a very sort of visual era and social media especially has been at the forefront of how artists are pushing out their music garnering fan bases. So I think pretty much every artist that I see now, young artists, regardless of gender, they have a stylist or they have very much this meticulous attention to how they look, what are the hottest brands [and] where they need to be shopping. Now it really is almost this expectation that everyone has a look, [and that] everyone has a favorite brand that they’re working with or a designer that they really admire.

I really appreciated that there was a scholarly type of approach to this book, and I also enjoyed how you injected your own experiences with hip-hop and fashion. Was this all planned?

So with this book, just a little bit of behind-the-scenes intel, I went through several editors. And with this book, I can say very confidently, I had a clear vision from day one from the title to the cover to how I wanted this book to flow. I was very much in the driver’s seat. And again, just to be totally honest, my editors didn’t want me to really include the personal aspects.

And I understand when it comes to nonfiction, especially nonfiction anthology, I think it’s a fine balance of showcasing the subject matter on its own while also when relevant, pulling in those lived experiences. So on one hand, I wanted the book to feel, as you’ve said, kind of this scholarly work. It showcases the importance and significance of the work, but I also didn’t want it to read a textbook.

It certainly can be used in academic classrooms, but I still wanted it to have that feeling that I wrote it and that there’s a reason that I’m the one writing this to really give that unique industry insider perspective, but also as a kid who grew up in this, loving it, observing it. So that was really a fine balance, and where I implemented my personal story are places that I think are very relevant and add to the narrative versus sort of diminishing the actual subject matter.

When you were piecing this together, did you have some figures that you felt you absolutely needed to speak with?

Insofar as actual individual voices, I really wanted to focus on people who aren’t oftentimes written about in the fashion media. They perhaps haven’t gotten their flowers: specifically highlighting a lot of important Black women, whether it be designer April Walker who was really a streetwear originator, and she came up with Karl Kani and Cross Colors and people like that. She was dressing people like Tupac and Biggie at the start of their careers. Later we meet people like Julia Chance and Sonya Magett from The Source. Later highlighting someone like Kimora Lee Simmons, who we all know from Baby Phat, but really Baby Phat has not been elevated to being that streetwear originator. It’s often still viewed as sort of an “urban line,” or it was just the “girl version” of Phat Farm. But in fact, Kimora was such an icon.

How do you feel about Baby Phat not being seen as an originating fashion house for the aughts, but despite Kimora Lee Simmons creating a blueprint for so many brands that exist right now?

Kimora Lee Simmons is really such a fashion icon for so many reasons. Her story, beginning as a model from St. Louis, being of Black and Asian heritage, at a very young age is walking the Paris Runways. Karl Lagerfeld, who was at Chanel at the time, really saw her as a muse and representative of what the future would be, this sort of idea of multicultural beauty. But she said at the time, I mean, that was very, very shocking because she didn’t look like all the other girls walking the runway. So she inherently had this keen sense of high fashion, the way the clothes would sit on a woman’s body, those really important aspects that she would later take on when she launched Baby Phat. And as the story goes, it was this idea of seeing what Phat Farm was doing for women, and it was just not something that she would ever wear.

So she decided to design a line that she and her friends would essentially want to wear from those fitted tees to the very curve-hugging jeans. She jokes that her jeans were the best jeans in the world because they really amplify everything. She was very much just a part of this sort of New York socialite world that she would have for the Baby Phat fashion shows. That was the creme de la creme in hip hop.

Her shows really were now what we would talk about—that’s where all the hip-hop celebrities came out. Everyone came to see and be seen. And I think that’s just a really interesting part of the conversation. And then for her just in general as a businesswoman, making sure that the models on the runway represented a diversity of looks, even in her own, just the people who worked at Baby Phat hiring women, hiring women of color, I think was very much something that she was a pioneer in. And now so many years later, looking back, we can see just the importance of her and that line.

You also deconstructed Lil’ Kim’s relationship with fashion in Fashion Killa. What led to that decision?

Lil’ Kim has obviously been a huge sort of proponent of fashion. We know her for so many signature looks, the colorful wigs, the furs, and the famous VMA look. There’s really no shortage of incredible Lil’ Kim fashion moments. But I think for me, it was very important to sort of go into her history as an artist and then later her trajectory in fashion. And it was very organic in that she was somebody because she represented beauty and sex appeal and confidence, and very much this rebellious spirit that I think really attracted people in high fashion, she was able to forge relationships with people like Donatella Versace, Marc Jacobs and David LaChappelle, where in many ways she wasn’t just wearing the clothes, she was a muse. And you could see that interaction and that mutual excitement from both the artists as well as from the fashion industry.

I think Lil’ Kim really has always been a risk-taker, and that’s something that in fashion, I think always sort of pays off. I mean, who can forget when she did the cover of Interview Magazine and her body was covered in those LV prints? So it’s even this idea of skin as a luxury item, and I can’t think of any other artist of that generation who would be so bold and also be able to pull it off other than Lil’ Kim. I think Lil’ Kim is another person who oftentimes, as I’m having conversations around the book, this idea of not really getting her true credit within the fashion industry. She should have gotten the cover of American Vogue decades ago, but the fact that it just didn’t happen, it still shows where hip-hop still played in the periphery.

One point that you made in the chapter centering on women in rap really stood out to me. You basically wrote that they were breaking down gender norms. Do you feel like this is something that some of the female rappers were doing and it’s most interesting to you?

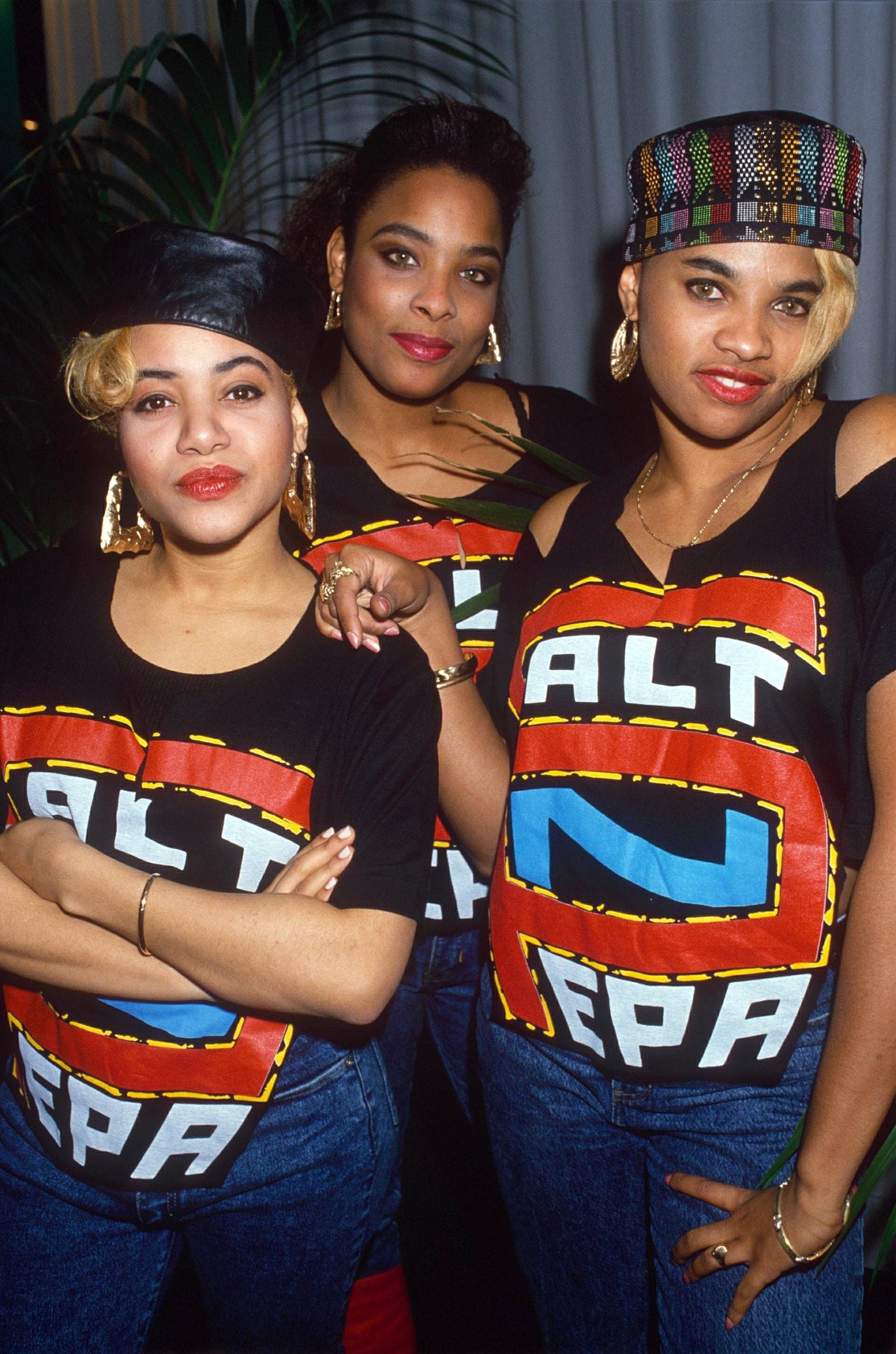

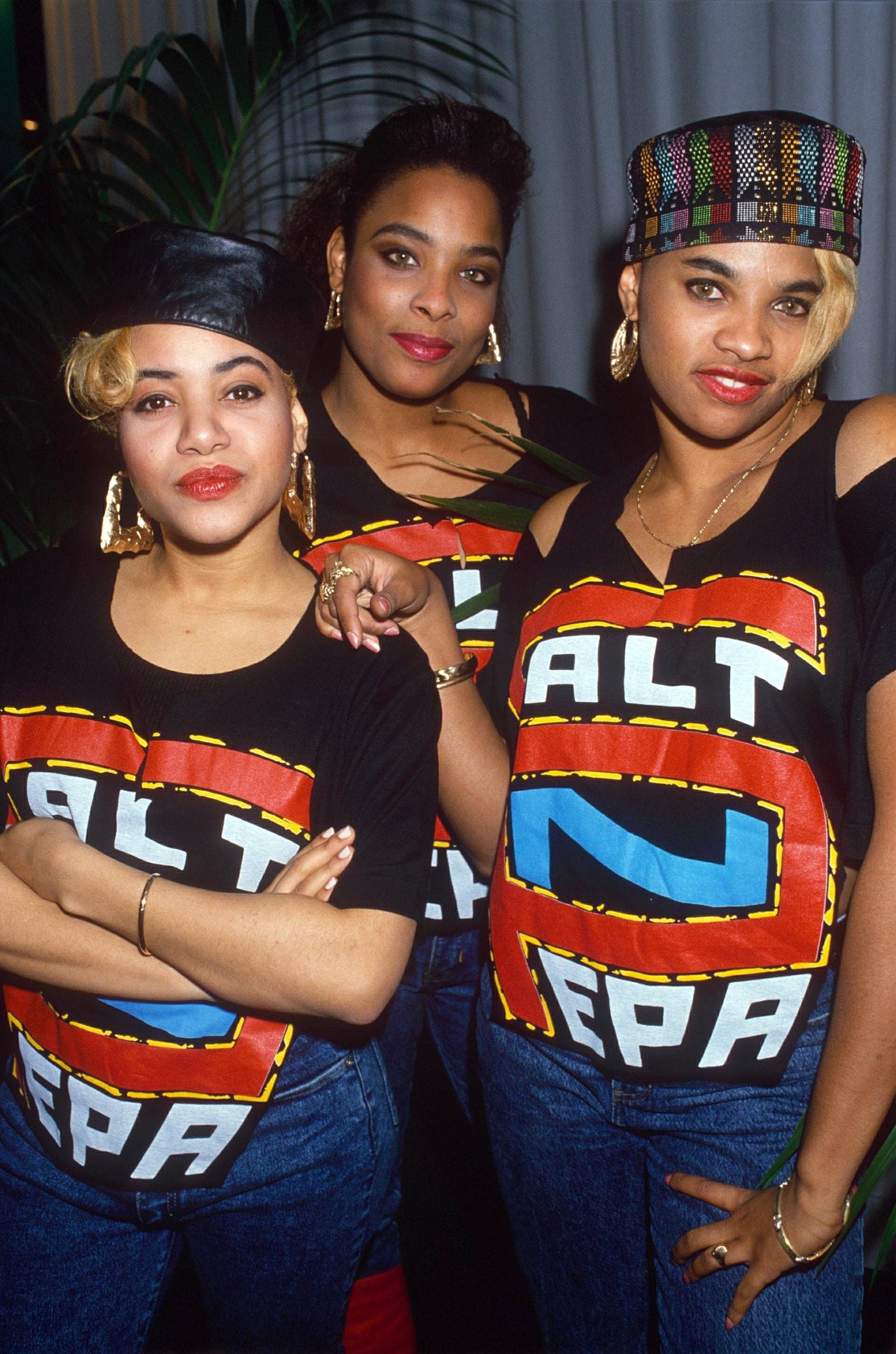

For women in hip hop, fashion has always been very powerful. So if we look in the past, oftentimes an artist such as MC Lyte, for example, really dressed in the trappings of her male counterparts. So it was like the baggy jeans, maybe the starter jacket, baseball cap, and it was this idea of really wanting that respect for her music, like treat me the same way that I’m just one of the guys. You look at someone like Queen Latifah who really took that name of Queen Latifah to create this very regal aesthetic for herself where just in how she walked and the way she dressed, she just garnered and demanded respect. As we get into the ’90s, we start to see artists like Lil’ Kim and Foxy Brown embracing this idea of female sexuality, that they can be sexy and raunchy and sexually active and really keep up with the guys.

Now we see women in hip hop, it’s still a constant battle because I do think the newest generation of artists are much more sex-positive. They’re able to be hypersexual if they choose, which is also a larger reflection of where we are in society from the late ’90s to now. That’s 30 years give or take. So things have also changed in American society as a whole.

I loved how you broke things down at the granular level in the chapter centering on Dame Dash, Jay-Z, buyer’s habits in the aughts, and the rise of Rocawear. How did you decide on that?

So for me, Roc-A-Fella is my favorite hip-hop label of all time, and I knew I had to include Rocawear, but what a lot of people don’t know is the genesis of Rocawear was when Jay-Z wanted to get a deal with Iceberg. I think Rocawear is such a great example of this confluence of the power of hip-hop fashion, but also this inherent entrepreneurial spirit, where especially as you’re starting to get to the mid to late ’90s, you’re seeing artists, they don’t just want to sign to a major label. They want to have their own imprint, they want to be their own boss. Roc-A-Fella especially very much reflected that when he first started, Jay couldn’t get a record deal, all the labels passed on Jay-Z. So really that necessity yielded them creating Roc-A-Fella. So it makes sense that that same kind of energy, that same sort of mentality that we are hustlers, we have that DIY ethos, it would permeate into their fashion line. When it comes to the actual rise of Rocawear, what they were able to do really well was leverage that incredible roster.

Everyone from Jay-Z to Cameron, they were wearing the clothes in the music videos, in the ads. At any point, it looked like a picture of the label roster was basically just a walking ad for the brand, and Dame was very smart in seeing we have that cultural currency, so why not leverage it, whether it be in fashion, in spirits with something like Armadale, into the film world, with the cult classic Paid in Full, we really can almost control entertainment from top to bottom. I also wanted to show some of the challenges. So just because they have this name in hip-hop doesn’t mean it translates into getting those clothes into the stores. And that’s where I wanted to sort of unearth a little bit of the mystery around how clothes get into stores like Bloomingdale’s at the time, Barney’s, Saks Fifth Avenue, all of these luxury retailers.

You can’t tell the story of hip-hop’s relationship without including Diddy and Sean John. You did an excellent job detailing this too, how did you decide what to depict?

Sean John really does represent the first hip-hop fashion line that I think truly got acceptance from the fashion industry. And that was something where Puffy really was adept at being this incredible dot connector, master of ceremonies. Everything is bigger than life with him, and it really was so representative of where he was at the time as a celebrity, as a fashion icon. So that Sean John story was very important.

[The brand] encapsulated this idea of really this hip-hop excellence and everything just being more looks and more aspirational. And he really did an incredible job with that. I think one thing that was very unique about him was even in the naming of his line, so that name came from Groovy Lou, the idea of using his government name, his first and middle name instead of something related to Bad Boy, for example, or calling it Puff Daddy, which was his moniker at the time. He decided to follow more in the steps of someone like Ralph Lauren or Tommy Hilfiger. I think even in just the naming, it was genius, it was this idea of differentiating himself from the other people who were also trying to garner that acceptance.

Did you have a goal when writing and completing Fashion Killa which is also your non-fiction debut?

For me, I mean, hip-hop, it’s the biggest genre in America, and to me, hip-hop is pop culture, and there’s no facet of celebrity that isn’t influenced by it. So it really made sense for hip-hop 50 to offer up this story. And my hope is that it really appeals not only to fans of hip-hop and fans of fashion, of course, but I think even someone who’s just interested in pop culture or American history, so much of what the book discusses is also going into things like sociology, psychology, other cultural phenomenon that was going on that affected this story.

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.