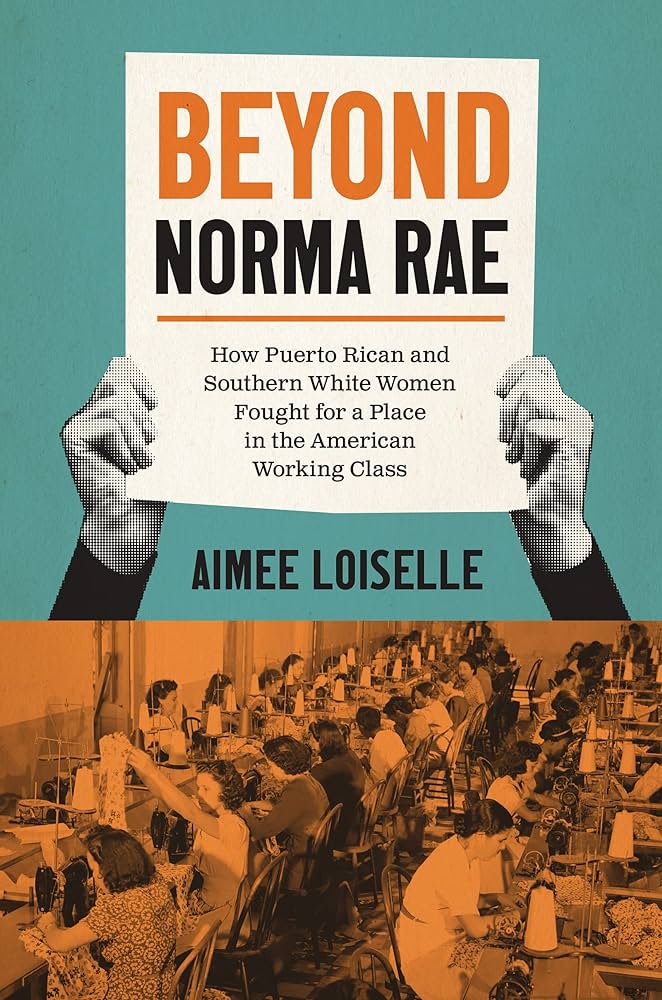

Aimee Loiselle is Assistant Professor of History at Central Connecticut State University. This interview is based on her new book, Beyond Norma Rae: How Puerto Rican and Southern White Women Fought for a Place in the American Working Class (University of North Carolina Press, 2023).

JF: What led you to write Beyond Norma Rae?

AL: I started with a general interest in working women in the 1970s, particularly low-wage factory workers. The 1979 movie Norma Rae became the foundation for the project because it continues to appear on cable television; labor groups still screen it at events; and the Norma Rae icon maintains its relevance as an adaptable symbol of defiance for television shows and websites. Norma Rae has serious cultural power to hold people’s attention 40 years later. I became curious about how it has shaped the way people think of American workers and individual defiance.

The movie tells the story of a Southern white woman in a textile mill, so I began researching that region. I had a loose acceptance of the notion that manufacturing relocated from the Northeast to the South and later the Global South. The first rupture in this thinking came during a conversation with a Puerto Rican woman and close friend. When I described my research, she told me that her mother had moved from Puerto Rico to New York City and then Massachusetts to work in apparel factories in the 1970s. That prompted immediate questions: where and when did Puerto Rican women work in textiles and garments, and were there any popular representations of them as industrial workers?

The fragmentation of textile and garment workers, labor archives, and historical scholarship and the concomitant gendered and racialized narratives of industry and American workers had obscured links between southern and Puerto Rican women. These conditions also cultivated Norma Rae and pushed it into popular consciousness as a canonical articulation of American workers. The movie derives from and reiterates such fragmentation, and the result perpetuates the erasure of Puerto Rican women from “the American working class.” Returning to that history offers a counter-narrative to the one perpetuated by Norma Rae, while the cultural history exposes the mechanisms by which popular culture reiterates gendered, racialized, nationalized, and individualized meanings.

JF: In 2 sentences, what is the argument of Beyond Norma Rae?

AL: Puerto Rican and Southern white women became workers and union members in the US textile and apparel industry during the first half of the twentieth century, but only Southern white women captured popular culture attention. When commercial media producers extracted and refined Crystal Lee Sutton’s experiences into the 1979 movie Norma Rae and its circulating icon, they reinforced the idea of one southern white underdog representing the American working class, which also helped serve the formation of neoliberal individualism in the 1980s – but Puerto Rican women like Gloria Maldonado continued their fight to change both working conditions and cultural meanings for American workers.

JF: Why do we need to read Beyond Norma Rae?

AL: This book breaks new ground in cultural history by bringing together the tools of labor history and history of capitalism. It argues that the process of turning the 1975 biography Crystal Lee: A Woman of Inheritance into the 1977 script “Crystal Lee” and the blockbuster 1979 movie Norma Rae reveals a fraught field of cultural production in which Sutton had limited economic and social capital but was still able to force changes on the $5 million Hollywood production. She also eventually used her symbolic capital to jam the movie’s marketing and distribution and to make financial claims against Twentieth Century-Fox. The book challenges historians’ use of big movies as reflections of society or as inevitable popular representations by analyzing the creative business decision-making that drives reiterations of gendered, racialized, nationalized, and individualized notions like the white American worker.

The book also transcends traditional geographic boundaries and practices of labor history by bringing Puerto Rican and southern white women in the US textile and apparel industry into one kaleidoscopic history. The book does not argue these women were equivalents or that Puerto Rico is rightfully part of the United States, but Beyond Norma Rae challenges the idea that women workers in different locations were not linked or did not understand the larger conglomerates and economic systems in which they worked. When corporations and managers collaborated to construct gendered and racialized labor markets run through with categories of citizenship and colonialism, these women were not supposed to know each other. Yet they migrated, organized, and resisted in pursuit of their own interests and ambitions and moved through the same companies and unions.

Lastly, Beyond Norma Rae exemplifies new practices of history in which scholars examine larger political-economic, social, and cultural structures while continuing to center ordinary people. Such practices acknowledge the material power of international, national, colonial, and state agreements, legalistic frameworks, and banking – with their force in workers’ lives – but without capitulating to them as absolutely hegemonic. This book focuses on low-wage women manufacturing workers to keep their actions and resistance at the forefront of historical analysis while linking them to US imperialism from the metropole to Puerto Rico to East Asia.

JF: Why and when did you become an American historian?

AL: I have been an American historian in various capacities. I was a history major who earned my secondary social studies (7-12) certification and taught US history to eleventh grade students from 1993 to 1999. I decided to go full-time for my MA in history, and became a graduate student writing scholarly modern US women’s history. Twenty years later, I became a doctoral student and committed to a career as a tenure-track modern US history professor. In 2021, I started as a history professor at Central Connecticut State University, where I bring together all my expertise as an educator, writer, and scholar to teach a variety of students, including those planning to earn their secondary social studies certification.

In each of these phases, I had a fascination with the interdisciplinarity of historical studies and how history illuminated so much of humanity. I appreciated the mix of political, economic and increasingly social and cultural aspects of societies over time. I had to teach as a generalist in the first half of my career so I still enjoy the broad sweep. Throughout the years, however, my interest in modern US women’s history remained consistent because the rich contextualization of recent events and de-mythologizing of contemporary cultural narratives both fascinated me and helped sharpen my feminist, environmentalist, and justice activism. I especially value intersectionality as an active tool.

I have always been interested in power, but not only in conventional top government figures. As I learned from my undergraduate studies of US civil rights activism and women’s liberation, power operates in multiple interactions and directions every day, whether people overtly acknowledge it or not.

JF: What is your next project?

AL: I plan to research the history of labor, manufacturing, and financial systems that served hip-hop lifestyle companies of the 1990s and early 2000s. Workers in this enterprise include women on the line in the apparel and perfume factories of Asia and models on the runways of New York City. When I taught my class, Hip Hop: A Social and Political History, I realized my central concerns in Beyond Norma Rae are relevant to the history of hip-hop fashion. Narratives of US entrepreneurs obscured dependence on transnational finance and the labor of low-wage women workers in long supply chains. Intersections of gender, race, ethnicity, and citizenship constructed the labor force as well as the cultural imagery that concealed the manufacturing workers while glamorizing others.

Globalization often appears as abstract and inevitable or as the purview of elites in international organizations and commerce. My research focuses on the US as a hub for transnational labor and capital within the intensifying economic, political, and military connections of the long twentieth century. This approach investigates globalization as an ongoing contest in which resources and power cohere in particular ways and move along lines continuously reshaped by multiple forces, from diplomatic pacts and currency exchange to women’s migrations and workers’ ties across US imperial sites. Despite the asymmetrical power distributed across structural hierarchies, working women’s labor, migrations, resistance, and demands have been constants in these contests over the form of globalization.

JF: Thanks, Aimee!

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.