The Pioneering, Barnstorming Women’s Basketball Stars of the Texas Cowgirls

The Texas Cowgirls weren’t all from the state, but the groundbreaking women’s pro team promoted itself with loads of Texas mystique.

Courtesy of Erin Hovland

On a cold Indiana night in late 1955, one year after graduating from the school, Linda Yearby entered the Chrisney High gymnasium with her basketball team. She wasn’t wearing the school colors of black and orange, but a blue uniform, striped socks, and white Chuck Taylors. Her teammates, who had all spent the previous night at her house, weren’t from the area. They were young women from Iowa, Arkansas, and beyond.

But their jerseys said “Texas.”

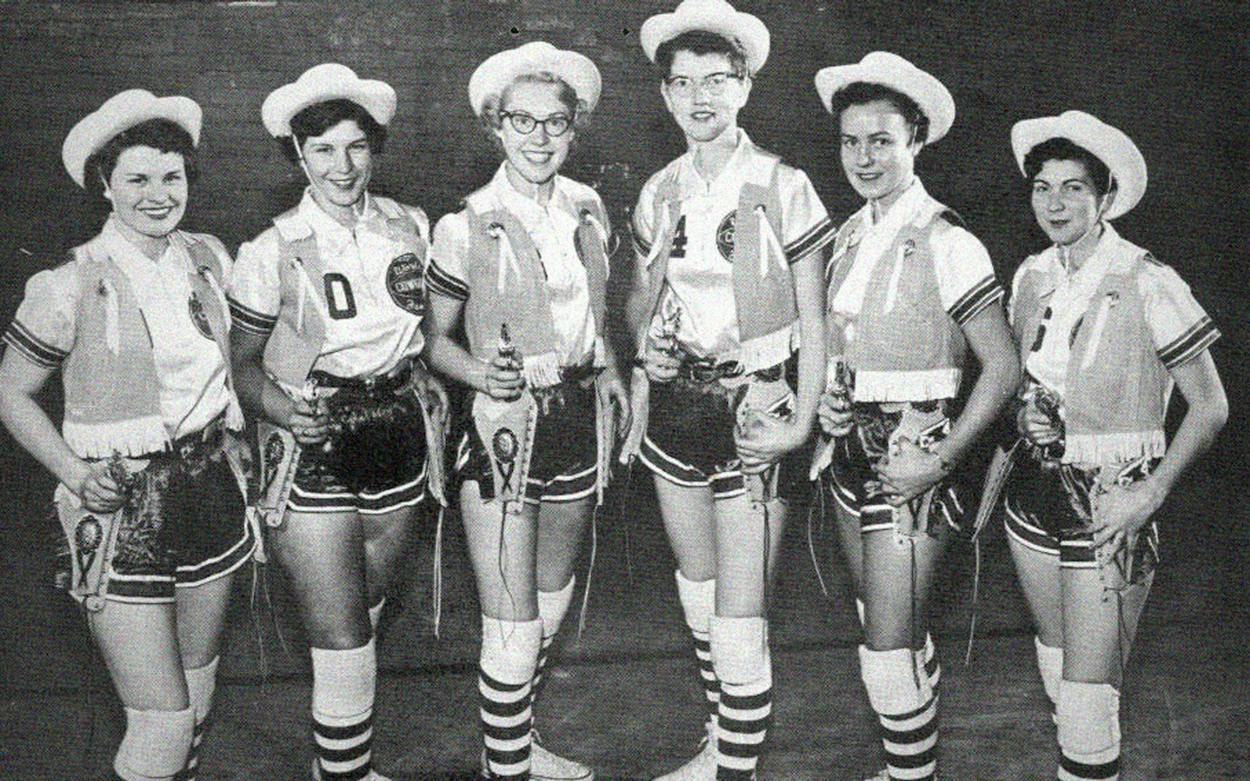

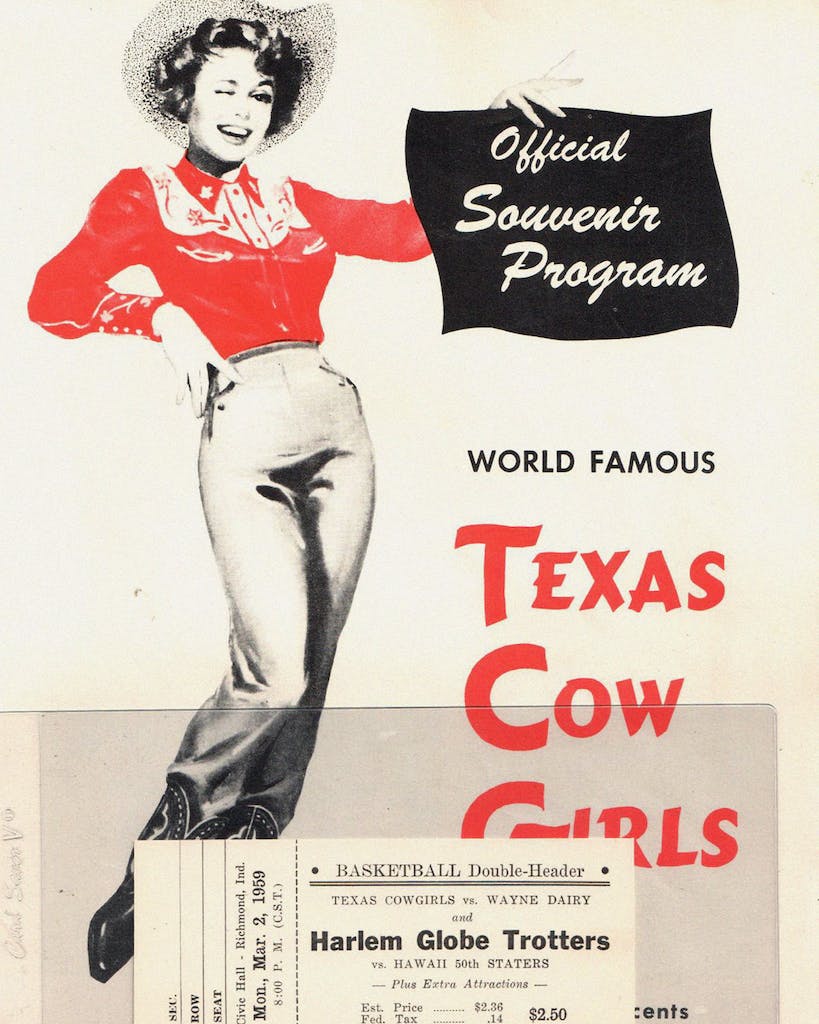

From 1949 to 1977, the Texas Cowgirls were the Harlem Globetrotters of women’s basketball. The team, drawing from the Globetrotters’ barnstorming model, gave young women like Yearby the opportunity to live out their dream of playing professional basketball. The Cowgirls also leaned in to the stereotypes of the state the team nominally represented, hog-tying opposing players, traveling with country music acts like Pee Wee King and Audrey Williams, and shooting referees with fake pistols. The women came from across the country, descending upon Chicagoland for an annual training camp before hitting the road, where they bonded over diner hamburgers, open road sing-alongs, and the game they loved.

Before Title IX, the NCAA, and the WNBA, the Cowgirls offered young women paychecks, travel, and the chance to play beyond their driveways and hometowns. Basketball gave them opportunity and a common ground. Texas gave them a name with which to promote themselves.

Which is how Yearby found herself in her former high school gymnasium wearing a blue uniform, a cowboy hat, and a fake pistol on her waist.

When it was showtime, she didn’t jog onto the court to the Chrisney alma mater, but to the Cowgirls’ entrance song: the classic fiddle tune “Orange Blossom Special.” Yearby and her teammates looped around their half of the court to warm up, shooting layups and shedding one element of the costume on each trip past the bench: hat, then belt, then vest. As the music died down, they assumed their formation for pregame introductions. Two perpendicular lines: a Texas T.

The announcer called each woman and her hometown as it was listed on the roster. Houston. Dallas. Austin. All Texas. All false. On the other end of the court, the night’s opponents, a squadron of local men, had stopped warming up to watch.

“A five-six guard from King Ranch, Texas,” boomed the announcer. “Linda Yearby!”

The five-two Hoosier stepped forward and waved. The hometown crowd roared. Then it was time to play ball.

Chicago’s Hotel North Park was big and glamorous, with cavernous ballrooms, window curtains as heavy as thunderclaps, and some of the best people-watching in the city.

It was the fall of 1949, and Dempsey Hovland, the future Texas Cowgirls owner and promoter but then–hotel employee, recognized Jack Kearns as soon as he walked in. Kearns had managed the heavyweight champion Jack Dempsey and notched boxing’s first-ever million-dollar gate. Barely into his thirties, Hovland harbored similar ambitions in the entertainment business.

At age ten, Hovland was putting out his own handwritten neighborhood newspaper. By age fifteen, he was bringing in national music acts to play at Waverly Beach, a venue on the Rock River just outside Beloit, Wisconsin. He served in the Army Air Corps and started his own barnstorming baseball teams. But his newest idea was his best yet. Lacking in neither confidence nor salesmanship, Hovland approached Kearns and invited him to the North Park barroom for a pitch.

Barnstorming teams were increasing in popularity at the time. Hovland himself had played multiple sports for the House of David, a Michigan-based Isaraelite community that began putting sports teams together in 1913 as a fund-raising and evangelism device. While overlapping on the same circuits, Hovland forged relationships with fellow barnstormers Satchel Paige, who would later travel with the Cowgirls and put on halftime pitching exhibitions, and Globetrotter Marques Haynes, who taught his dribbling routine to Cowgirls players. But, as Hovland laid out for Kearns, the existing teams and circuits were made up of men. What about a women’s team that combined great basketball with the Western aesthetic made popular at the time by Patsy Montana, Dorothy Page, and Barbara Stanwyck’s portrayal of Annie Oakley?

Kearns saw the ambition and street sense oozing from the young man before him. He agreed to book Chicago Stadium as the venue for his first game in two weeks’ time. If all went well, Kearns would invest.

With the tight turnaround, Hovland managed to assemble a short order lineup of five women. He wanted a bench, too, or at least the appearance of one, so he called his buddies from the House of David. Four of his former teammates traveled to Chicago for the game. Three of those men, Doc Hallisey, Vincent Stankowitz, and Don Tamalous, stopped at a local salon, outfitted themselves with wigs, makeup, and sweat pants, and made their way to the arena dressed as Texas Cowgirls. They didn’t play; they only sat on the bench to provide the appearance of a full team. Kearns was impressed enough to give Hovland enough money to start. From the depths of Chicago, the Texas Cowgirls were born.

Each season began with a September summit, a tryout, and then a training camp held in some Midwestern city: Chicago; Bismarck, North Dakota; South Beloit, Illinois; Rockford, Illinois. Players stayed in rented cabins or in the basement of the Hovland house and trained at nearby gyms. Sometimes the Globetrotters stopped by, but more often the women tuned up by scrimmaging groups of local men. On and off the court, it was an adjustment.

“Most of us only played half-court in high school; that’s all they would allow us,” says Bonita Smith McKnight, who played with the Cowgirls during the 1964–65 season and now lives in Texarkana, Arkansas. “So we had to get used to playing both ends of the court.”

Their legs under them and their performances in place, the Cowgirls loaded into the team’s Mercury station wagon (later a van, sometimes a limo), and the tour began. To go along with a per diem for food, payments rose through the years from $7 per game in 1950s to $13 by the 1960s and 1970s. A typical season included more than a hundred games, but the thrill was enough to override any travel fatigue. The routine stayed the same: play, load up the car, drive to the next town, bunk in a motel, wake up, eat fast food, do it again.

The Cowgirls played everywhere from Linda Yearby’s Chrisney High School to Madison Square Garden. They served as the opening act for NBA games and for the Globetrotters. They played at military bases and in Europe; at the Cow Palace and the Corn Palace; in Maine, California, and Alaska, yet none of the players interviewed for this article remember playing in Texas. Perhaps the spectacle would have fallen flat on true Texans, or maybe the distance between towns in the state was too great for the team’s condensed schedule. Still, Hovland continued leaning in to the Cowgirls’ brand, even striking up an endorsement deal with Levi’s that included national magazine ads featuring Cowgirls players as models. Many newspapers, for their part, had no idea the women were from elsewhere.

“The Texas Cowgirls basketball team has some tall timber on it just as you might expect to see on any quintet from the Lone Star State,” read a story from the Provo, Utah, Daily Herald in 1962.

One Minnesota newspaper was fooled by both the branding and the women’s proficiency in the full-court game.

“All of the girls are from Texas, where almost all played interscholastic high school basketball under rules identical to those used by boys’ teams,” wrote a journalist in the Minneapolis Star in 1970.

The roster was a diverse makeup of backgrounds, personalities, and, by the 1970s, races. But, as if everyone really had come from the same state, the schedule fostered a cohesive singularity.

“We was all just like one family,” says Joann Knight, who played with the team in the early 1970s. “No white, no Black, just all as one family.”

Joann Knight and Ella Mae Knight are not related, but both grew up in Mississippi. Joann grew up in rural Greenfield, where shooting hoops was a reprieve from the toil of working the cotton fields on her father’s twelve-acre farm. Ella Mae grew up playing on a hoop nailed to the tree in an alley near her house on Elm Street, in midtown Jackson. One from the country and one from the city, both from Black communities in the Deep South. Joann and Ella Mae had each been star high school players who were invited to play for Hovland’s other team, the Harlem Queens.

Through the 1950s, the Cowgirls were a predominantly white team. Hovland started another team, the Harlem Chicks, made up of women of color. The teams were branded differently but played similar schedules and circuits. Hovland spent much of the early fifties on the road managing the two. As the decade wore on, with his family and list of business ventures growing, he began staying home and leaving the players in charge of the day-to-day.

“Linda [Yearby] was the one who came to get me in the station wagon in Tennessee and drive me back to Beloit,” remembers Irma Bradford of her trip up to Chicks training camp in 1959.

Around 1967, Hovland changed the Chicks’ name to the Harlem Queens, and in 1973 he combined the roster with the Cowgirls. Soon the Texas Cowgirls had nearly as many Black players as white. Joann Knight and Ella Mae Knight spent time on both the Queens and the Cowgirls.

Ella Mae had not left Mississippi prior to joining the Queens, in 1969. She moved over to the Cowgirls soon after, and she remembers that while she always felt comfortable with her teammates, the surroundings, crowds, and lifestyle felt new.

“There were a lot of white people, so being from Mississippi, I was really skeptical about it, but they welcomed me with open arms,” she says. “I remember one time our bus broke down and this couple came and got us and invited us into their home so we could stay there overnight.”

Joann spent some time in Chicago between graduating from Carter High School in Mississippi and joining the Queens/Cowgirls. Still, the experience was novel to her as well. Carter wasn’t integrated when she attended the school, and she had never had white teammates before the Cowgirls.

Both the Cowgirls and the Queens were largely treated with respect by fans and their male opponents. Even after the team integrated, the players encountered little controversy or adversity on the road or the court. That sense of fellowship came from within, the players unified in their love of the game.

“I felt like we all grew up together,” Ella Mae says of her Cowgirls teammates. “We was that close.”

It was the 1970s, and the Cowgirls were pulling players from more states and more backgrounds than in previous decades. After a period apart, the team had reestablished a business relationship with the Globetrotters, and national interest in women’s sports was expanding. The Commission on Intercollegiate Athletics for Women sponsored the first postseason women’s collegiate basketball tournament in 1969. Title IX was born in 1972, and the Women’s Professional Basketball League, the first of its kind in the U.S., was formed in 1978. In 1982, the NCAA women’s basketball tournament was born.

The conditions were in place in the late 1970s for the Cowgirls to land more sponsorships and generate mainstream awareness, like their Globetrotter counterparts had done, but Hovland’s health was failing, and with it went the prospects of the team he had hustled into existence nearly three decades prior. The Cowgirls’ last game was in 1977. Hovland, after years of battling diabetes and multiple heart attacks, died of an aneurysm in 1979.

Following their time with the Cowgirls, some women, like Bonita Smith McKnight and Ella Mae Knight, never played competitive basketball again. In 1964, Linda Yearby was part of a group of women who formed a new barnstorming team, the Shooting Stars (later renamed the Arkansas Lassies). Yearby was recently inducted into the Indiana Sports Hall of Fame. She says the Cowgirls gave her a platform from which to share the game she loved with those who came after her.

“As long as I was playing, I could be teaching the little ones how to play,” says Yearby, now 88. “I was trying to help every little boy or girl—no matter who—to show them a lot of things about basketball that kids don’t know. It takes a teacher who has been there. I’m not really a teacher, but I’m a teacher in sports.”

“We did feel as though we were doing something special,” adds Joyce Eastman, who played seven years for the Cowgirls, beginning in 1960, and now lives in New Mexico. “I don’t think we knew how special it was at the time.”

Decades have passed, and many memories have faded, withered, or died altogether, but certain details persist in the mind of every former Cowgirl: the thrill of playing professional basketball; the chords of their entry song, “Orange Blossom Special”; and their made-up Texas hometowns.

“Corpus Christi,” says Ella Mae Knight.

“Austin,” laughs Joyce Eastman.

“I was from . . .” starts Joann Knight, before correcting herself. “I was supposed to be from Dallas.”

- More About:

- Sports

- Texas History

- Basketball

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.