The Bloomsbury Group Is Back in Vogue

In July, 1918, Virginia Woolf spent a weekend at Garsington—a country home, outside Oxford, owned by Lady Ottoline Morrell, a celebrated hostess of the era, and her husband, Philip Morrell, a Member of Parliament. The house, a ramshackle Jacobean mansion that the Morrells had acquired five years earlier, had been vividly redecorated by Ottoline into what one guest called a “fluttering parrot-house of greens, reds and yellows.” One sitting room was painted with a translucent seafoam wash; another was covered in deep Venetian red, and early visitors were invited to apply thin lines of gold paint to the edges of wooden panels. The entrance hall was laid with Persian carpets and, as Morrell’s biographer Miranda Seymour has written, the pearly gray paint on the walls was streaked with pink, “to create the effect of a winter sunset.” Woolf, in her diary, noted that the Italianate garden fashioned by Morrell—with paved terraces, brilliantly colored flower beds, and a pond surrounded by yew-tree hedges clipped with niches for statuary—was “almost melodramatically perfect.”

Woolf characterized Morrell herself with a note of satire, observing that her conversational “drift is always almost bewilderingly meandering.” While on an afternoon walk, Morrell had leaned on a parasol and offered a discourse on love—“Isn’t it sad that no one really falls in love nowadays?”—before declaring her dedication to the natural world and to literature. “We asked the poor old ninny why, with this passion for literature, she didn’t write,” Woolf wrote. Morrell replied, “Ah, but I’ve no time—never any time. Besides, I have such wretched health—But the pleasure of creation, Virginia, must transcend all others.”

Morrell, who was born in 1873, just nine years before Woolf—hardly an old-ninny interval—may not have written novels, but she certainly took pleasure in creation. As if to accompany her lush décor, she cultivated an extravagant persona, especially through her clothing. Her contemporaries found the performance at once irresistible and risible. The poet and writer Siegfried Sassoon, visiting Garsington in 1916, remarked on Morrell’s “voluminous pale-pink Turkish trousers.” Desmond MacCarthy, the British critic, described one of Morrell’s hats as being “like a crimson tea cosy trimmed with hedgehogs.”

Morrell is one of the most chronicled and caricatured figures connected with the Bloomsbury group, the association of writers, artists, and thinkers who, in the early twentieth century, shared living spaces in a district of London known for its leafy squares, and whose intellectual and erotic paths intertwined well after those residential arrangements ended. Lytton Strachey, the critic, who was a frequent guest of Morrell’s, said that she was, like Garsington itself, “very impressive, patched, gilded and preposterous.” According to the artist Vanessa Bell, Woolf’s sister, Morrell had “a terrifically energetic and vigorous character with a definite rather bad taste.” D. H. Lawrence—not himself a part of the Bloomsbury group, but well acquainted with its members—drew on Morrell in his characterization of Hermione Roddice, the aloof, domineering heiress in “Women in Love.” (“People were silent when she passed, impressed, roused, wanting to jeer, yet for some reason silenced.”) Morrell, who kept a diary, declared in one entry that “conventionality is deadness,” but she was conventional enough to be hurt by her friends’ sniping. Lawrence’s portrait extinguished their friendship.

Lady Ottoline’s marriage to Philip, which began in 1902, combined observance of convention with its subversion. The Morrells had two children—a daughter, Julian, and her twin brother, Hugh, who died soon after birth—and remained together until Ottoline’s death, in 1938. But both had numerous external relationships. Around the time of Virginia Woolf’s visit to Garsington, Philip fathered two children outside his marriage, one with his secretary and another with his wife’s former maid. Ottoline, meanwhile, was engaged in a long-term affair with the philosopher Bertrand Russell. Another of Ottoline’s lovers had been Augustus John, the artist, whose painting of her, made in 1919, today hangs in the National Portrait Gallery in London. Ottoline, who was six feet tall even before putting on the scarlet high heels she favored, is dressed in a black velvet gown with enormous puffed sleeves and a square neckline edged with lace, and wears atop her massed auburn curls a gargantuan black hat. She lifts her chin and looks sidelong down her nose, the regard in her deep-set eyes striking a precarious balance between imperiousness and insecurity.

One morning this past July, Sarah Glenn, a textile conservator based in London, eased a protective sheath off a tailor’s dummy in her studio, in the Battersea district, to reveal a dress belonging to the collection of the Fashion Museum in Bath. The black velvet evening gown, which had a square neck edged with lace, puffed sleeves, and a fishtail skirt, had once belonged to Lady Ottoline. It may not have been the exact one she wore while sitting for Augustus John; Morrell had loved the style so much that she had owned repeat models over the years. Exposed on either side of the rib cage was a pair of heavy-duty zippers—an innovation introduced to dressmaking during the Jazz Age. The tubular sleeve was so narrow that Morrell must have found it challenging to bend her elbows. At the upper arm, the sleeve burst into a voluptuous puff, which would have made Morrell’s shoulders appear as broad as a rugby player’s. With a silhouette that offered exaggerated nods to both femininity and masculinity, the dress was less clothing than costume; its gender ambiguities brought to mind Rei Kawakubo’s archly stylized designs for Comme des Garçons, with their distorted shoulders and hips. The gown, probably fabricated by Morrell’s longtime dressmaker, was a bold expression of Morrell’s creativity, with herself as the medium.

The velvet dress, along with several other items from Morrell’s wardrobe, goes on display this month in an exhibition, “Bring No Clothes,” which explores the Bloomsbury group’s use of, and influence on, clothing and fashion. (The title quotes an instruction that Virginia Woolf gave to T. S. Eliot in 1920 before he joined her for a weekend in the country—she was encouraging him to leave constrictive finery behind.) The show, curated by Charlie Porter, a fashion journalist and the author of “What Artists Wear,” is being held in Lewes, a town in East Sussex, at a new gallery run by the Charleston Trust, which also owns the seventeenth-century farmhouse, seven miles outside town, that was once the home of Vanessa Bell and her sometime partner Duncan Grant, the artist. Bell was in what amounted to an open marriage with the art critic Clive Bell, and took up residence with Grant during the First World War, when Grant, a conscientious objector, needed to find farmwork, an approved alternative to fighting. Though Grant generally slept with men—among them the writer David Garnett and the economist John Maynard Keynes, both of whom spent many nights at Charleston—he and Vanessa Bell had a child together, Angelica, who was born at the farmhouse. (Angelica later added a further tangle to these arrangements by marrying Garnett.) Vanessa Bell died in 1961, and Grant continued to live at Charleston until his death, in 1978. The house subsequently became a museum. It stands next to a working farm, complete with the evocative smell of the barnyard.

During Bell and Grant’s tenure, the house was idiosyncratically decorated by its inhabitants, in a joyful blurring of the boundary between art and life. The walls, the furnishings, the mantels, the woodwork, and even the sides of a bathtub were riotously painted with floral and geometrical patterns, still-lifes, and sturdy nudes. The shared spaces and the bedrooms were occupied by spouses, lovers, and friends, among whom habits of Edwardian decorum were happily discarded. Virginia Woolf, for one, was married to the scholar and editor Leonard Woolf, but she had romantic relationships with women, most notably the writer and garden designer Vita Sackville-West.

In recent years, a new space has been added to the Charleston site, offering temporary exhibitions of contemporary artists working in the spirit of Charleston’s earlier occupants. (An upcoming show centers on intimate drawings by David Hockney of friends and lovers in domestic settings.) Under its current director, Nathaniel Hepburn, who took over in 2017, Charleston has embraced more fully its heritage as a site of radical politics and personal self-invention—or, as Hepburn told me, “a place where people came to imagine how life might be lived differently.”

The new gallery in Lewes, in a former office building, is an extension of this mission. “Bring No Clothes” emulates Charleston’s mode of casual ornamentation: there are no fastidiously reconstructed interiors with mannequins posed on chairs. Instead, the show wittily throws together a wide range of objects, both historical and contemporary. In a section devoted to Bloomsbury’s affinity for handcrafts, a series of portraits of Vanessa Bell is shown alongside a multicolored rag rug fashioned from her worn-out clothing—an artifact recovered from the drafty floors at Charleston. A copy of “Orlando,” Virginia Woolf’s 1928 novel about a gender-switching aristocrat, inscribed to Sackville-West—the inspiration for the story—is displayed, as are three costumes that Kawakubo designed for a 2019 operatic adaptation of the book, by the composer Olga Neuwirth.

Porter has also included items from contemporary artists and designers who share a kinship with the group. These include Jawara Alleyne, a Jamaican-born designer whose use of safety pins to fasten slashed fabric echoes the handmade aesthetic of Charleston, and Ella Boucht, a young London-based designer who creates tailored clothes and leather garments that celebrate butch identity. Among other things, the exhibition makes a strong case that the Bloomsbury group’s approach to resisting social norms—playful, exploratory, ever-shifting—set the stage for current notions of gender and sexual fluidity. Clothing was never the focus of the group, but, as Porter’s exhibit text notes, “fashion provided a language with which to explore their break away from tradition.”

Few garments that belonged to the key members of the Bloomsbury group have survived. Scholars have written about the significance of gloves in the novels of Virginia Woolf; in an early iteration of “Mrs. Dalloway,” “Mrs. Dalloway in Bond Street,” it is gloves rather than flowers that Clarissa Dalloway says that she will buy herself in the first line. But none of the gloves that Woolf wore in her lifetime are thought to exist today. The only piece of Woolf’s clothing known to have survived is a black Chinese-silk shawl decorated with green foliage and salmon-colored flowers and birds. It was a gift from the generous Lady Ottoline Morrell.

How Woolf, Bell, and others dressed, and how they thought about what they wore, has been preserved principally in their texts, photographs, and art works. On display in Lewes is the diary of Grace Higgens, who served as a housekeeper for Vanessa Bell and Duncan Grant at Charleston, which reveals with clarity what happened to Bell’s clothing after her death: “Had a bonfire & burnt Mrs Bells mattress & lots of her clothes, & pillows.” Porter told me, “It confirms the absolute absence of sentimentality about clothes. From this, you can kind of presume what happened to Virginia Woolf’s clothes. There would have been no sense of holding on to things.”

In the letter in which Woolf advised T. S. Eliot to “bring no clothes” for a visit to the country, she added, by way of explication, “We live in a state of the greatest simplicity.” In conventional society of the time, hosts and guests at a country house would change their clothes several times a day, culminating in a formal outfit for dinner. Woolf may have dispensed with such rules, but she was hardly free of anxiety about clothing. Her journals are filled with comments about the inadequacies of her wardrobe. On multiple occasions, she decries herself as badly dressed (a verdict sometimes endorsed by other members of her circle). In 1915, Woolf considers attending a party, reminding herself that she will “see beautiful people, & get a sensation of being on the highest crest of the biggest wave,” then decides against it. “There is vanity,” she writes. “I have no clothes to go in.”

Judging by photographs taken at Garsington and elsewhere, Woolf appears to have settled at a young age on an aesthetic—long, lean lines, with little trussing at the waist or fussing at the neckline—that rejects some of the strictures of dress placed on women in the first decades of the twentieth century. But, if Woolf was careless of certain Edwardian forms of sartorial constraint, she was mindful of others: “It seems to me quite impossible to wear trousers,” she wrote in a 1917 letter, observing the bolder choices of others, such as the artist Dora Carrington—who preferred to be called by only her last name. Carrington wore corduroy trousers and jodhpurs, and styled her hair in a short, blunt bob that threatened to obscure her face. Porter has found a snapshot of Woolf reclining outdoors on a chaise longue during a vacation in Devon, dressed in what she would have meant by “no clothes”: a loose sweater and a calf-length skirt revealing stockings and leather pumps.

If Woolf found self-expression through dressing down, she was also aware of the pleasure and the power offered by dressing up. In April, 1925, just before the publication of “Mrs. Dalloway,” Woolf wrote in her diary of the happiness of commissioning a new garment: “Going to my dressmaker in Judd Street, or rather thinking of a dress I could get her to make, & imagining it made—that is the string, which as if it dipped loosely into a wave of treasure brings up pearls sticking to it.” A few days later, she expressed a desire to explore “the party consciousness, the frock consciousness, &c.”—her now celebrated coinage for the ways an individual’s sense of self can be altered by what she puts on her body. Her reflections were prompted by a visit, earlier that day, to a studio in the Marylebone district of London, where she sat for Maurice Adams Beck and Helen MacGregor, the chief photographers of British Vogue. In the resulting portrait, she sits in a dark dress, one hand sheathed in a pale glove, with its mate resting on her lap. The experience had given her occasion to consider the exclusionary function of the fashion system, “where people secrete an envelope which connects them & protects them from others, like myself, who am outside the envelope, foreign bodies.”

In addition to being formally photographed by professionals, Woolf and her circle were captured in casual snapshots. Porter has rummaged through Bloomsbury albums for images, and among his finds are photographs of Grant and others shirtless, semi-clothed, or naked—a freedom permitted by the privacy of the enclosed gardens at properties such as Charleston and Garsington. (One can presumably still streak at Garsington, which remains a private home.) Lady Ottoline Morrell frequently brandished a camera, capturing her guests in moments of relaxed deshabille, or in bohemian tea-party ensembles. She pasted the photographs into albums and often gave copies of the images to the subjects; many of them are now in the collection of the National Portrait Gallery.

Though the luminous color combinations painted on the cupboards and mantelpieces at Charleston suggest that the Bloomsbury group embraced an adventurous palette, it is hard to say how far this approach was extended to clothing, given that its members were photographed almost exclusively in black-and-white. (In a 1911 Duncan Grant portrait of Woolf, her sitting figure is surrounded by Fauvist swaths of orange and green, but her dress is rendered in black.) A photograph from 1923 shows Woolf seated on a garden bench at Garsington, smoking a cigarette and wearing a long, unstructured pin-tucked dress, a lace shawl, and a broad-brimmed hat trimmed with pale feathers. One can only guess at the combination of colors and tones. The written record, at least, suggests that Woolf’s palette could be vivid. Sackville-West, whom Woolf met in the early nineteen-twenties, remarked in 1922 that Woolf was dressed more smartly than she had last seen her: “That is to say, the woolen orange stockings were replaced by yellow silk ones, but she still wore pumps.” Porter has observed, aptly, that the description “sounds like a styling decision taken today backstage at Prada.”

Similarly, Porter unearths accounts by Woolf and others that reveal what surviving photographs obscure. In a 1916 letter from Woolf to Bell, the outfit of their sister-in-law Karin Stephen, designed by Bell, is described sardonically as “a skirt barred with reds and yellows of the vilest kind, a peagreen blouse on top, with a gaudy handkerchief on her head.” Woolf jokes, “I shall retire into dove colour and old lavender, with a lace collar and lawn wristlets”—the Edwardian colors and styles that the sisters had clearly left behind.

It is an accident of fate—and of class—that Lady Ottoline Morrell’s clothes were preserved by her descendants after her death. Her wardrobe offers a rare sample of the material texture of Bloomsbury, and the inventive ways in which its members sought to fashion themselves anew. At the exhibition, Morrell’s garments have been lined up like runway models at the end of a contemporary designer’s show. “Morrell spoke in her journal of how her preferred look was long and plain—she thinks her look is very simple,” Porter said. “But it seems to me that she is responding to her own features and exaggerating things because of the way she looked herself, rather than trying to hide anything.” Given Morrell’s height, hair, and hauteur, she was well aware that she looked striking and odd. Indeed, her appearance qualified as what she and her contemporaries would have called “queer”—that is, peculiar. In “Women in Love,” Hermione Roddice is described as “waving her head up and down, and waving her hand slowly in dismissal, smiling a strange affected smile, making a tall queer, frightening figure.”

Alongside the “Bring No Clothes” exhibition, Porter has published a book that shares the title. In both, he aims to demonstrate how people in the Bloomsbury circle used clothing, fashion, and the rejection of fashion to liberate themselves in a way that presages the modern usage of “queer” as an umbrella term for “not straight.” “I describe myself as ‘queer’ rather than ‘gay,’ even though I am a gay male,” Porter writes. “The word is specific enough to have meaning, broad enough to give all queer humans the space to be themselves.”

Porter is not alone in the world of the arts and fashion in finding that the Bloomsbury group speaks to contemporary notions of queerness: the actor Emma Corrin, who is nonbinary, recently starred in a West End adaptation of “Orlando,” which the lesbian writer Jeanette Winterson has categorized as “the first English language trans novel.” The British designer and artist Luke Edward Hall—whose interior schemes for homes, restaurants, and retail venues, with their clashing patterns and vibrant colors, are informed by the aesthetic of Charleston—has recently launched a line of home goods and gender-neutral clothing, called Chateau Orlando, that includes baggy floral shorts and the kind of boxy sweater-vests that are perfect for a weekend in an inadequately heated country pile. Porter writes that, if Woolf were alive today, “we might imagine her identifying as non-binary or trans.” At the same time, he acknowledges that it is anachronistic to re-gender people who lived a century ago. What Woolf writes of the Elizabethans in “Orlando”—“Their morals were not ours; nor their poets; nor their climate; nor their vegetables even”—is equally true today of our distance from the Bloomsbury era.

Porter’s most novel contribution to Bloomsbury scholarship is to look at the group’s artifacts from the vantage of contemporary queer culture. He offers an analysis of a portrait painted by Duncan Grant of his friend Harry Daley, a policeman who had a long affair with the Bloomsbury-group associate E. M. Forster. Daley, unusually for the time, was relatively open about being gay—protected from the legal prohibition on homosexuality by his position in law enforcement. Porter, writing about Daley’s snug police uniform, which is garlanded with chains and buckles, notes, “Daley is entirely covered, but to queer eyes the coded language of the garments tells a different story. . . . It speaks of fantasies in which a policeman forces a suspect to submit, or conversely, a suspect gets the upper hand.” In the book “Bring No Clothes,” Porter gives what stands for a credo: “The queer members of the Bloomsbury group had to navigate prohibitive societal norms to find ways to exist. By looking at their clothing, these strategies for living come to the fore. It can make us realize that, even today, we all live by such codes, as much as we believe that we are free.”

Just as Vanessa Bell painted her wardrobe and her fireplace with highly personal designs, she made her own clothes, sometimes from textiles that she had created. These garments were proudly unfussy, with ragged hems, and at least some of them were colorful. In a 1915 letter, Bell told Grant she was making a dress that “will be mostly purple,” adding, “I’m going to make myself a bright green blouse or coat.” Grant, for his part, improvised turbans out of lengths of cloth, and mixed styles with dashing ease: Woolf wrote that, at Charleston, Grant could be found “incredibly wrapped round with yellow waistcoats, spotted ties, & old blue stained painting jackets.” The D.I.Y. aesthetic of Charleston has inspired Porter to explore making his own clothes. The first time I met him, he wore a pair of lightweight pants with a ribbed elastic waistband, like maternity wear, and a shirt fashioned from two panels of cotton in different patterns and of different lengths, so that the front was shorter than the back. In “Bring No Clothes,” he writes, “Spending this time with the Bloomsbury group has pushed my thinking about garments wide open.”

The mishmashed Bloomsbury aesthetic continues to inspire. For many interior designers, the painterly clutter of Charleston offers an alternative path after decades of white walls and sleek industrial furnishings. At the bar of the Beaverbrook Town House, a new hotel in the Chelsea district of London, teal tiles and maroon glass clash delightfully with crowded shelves of ornately patterned pottery. English designers such as Tess Newall and Jermaine Gallacher have made a specialty of applying whimsical designs directly to walls. Architectural Digest, which recently declared that the “irreverent chic” of the Bloomsbury group “is making a comeback,” quoted Gallacher as saying that, whenever he designs a space, he tries “to include a cheeky mural or hand-painted surface.”

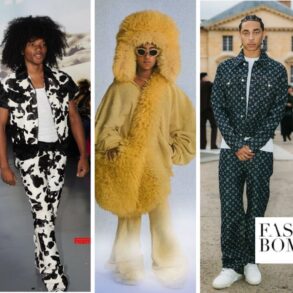

Today’s fashion runways are full of the kind of gender play favored by the Bloomsbury set. The fall/winter, 2023, collection of Prada prominently features ties for women; Armani, meanwhile, is offering patterned shawls for men. The kind of brightly colored stockings that Woolf favored are back in style, too. For some contemporary fashion designers, Bloomsbury is a central point of reference. Among them is the British Turkish designer Erdem Moralioglu, whose spring, 2022, collection was inspired both by Lady Ottoline Morrell’s clothes and by Dame Edith Sitwell, a Bloomsbury satellite whom Woolf described, upon first meeting her, as “a very tall young woman, wearing a permanently startled expression, & curiously finished off with a high green silk headdress.” Moralioglu told me that he finds the Bloomsbury era “such an interesting, progressive time,” adding, “The fluidity between relationships was fascinating.” His collection included slim floral dresses with flared skirts that hit mid-calf, broad-brimmed hats, and sensible brogues of the sort in which one might comfortably climb a country hillside, lean on a parasol, and announce one’s dedication to the natural world and to literature. The runway show took place in Bloomsbury, at the British Museum, laid out beneath that institution’s neoclassical colonnade, so that the models were quite literally following in the footsteps of their historical antecedents.

Perhaps the fashion industry’s most prominent Bloomsbury aficionado is Kim Jones, the artistic director of Fendi womenswear and Dior menswear. Jones, who is forty-four, spent time in Lewes growing up, and first visited Charleston on a school trip when he was in his teens. “It struck a chord with me—the way that these people lived exactly how they wanted to live,” Jones told me. “It was almost like punk. They really shook off the semblance of Victoriana they grew up with.” In recent years, Jones’s success as a designer and a fashion executive has given him the resources to amass an enormous library of manuscripts, letters, paintings, and objects related to the Bloomsbury group. Among the letters is a 1923 note that Virginia Woolf sent to T. S. Eliot, in his capacity as editor of the Criterion, offering him “Mrs. Dalloway in Bond Street” for publication. (Eliot declined.)

When Jones was creating his spring, 2023, collection for Dior Men, he immersed himself in the life and aesthetic of Duncan Grant. The resulting collection offered baggy, flapping raincoats, chunky shoes, and shorts paired with thick socks—a fantasia on the kinds of garment Grant wore to dash from the painting studio to the walled garden at Charleston. Several items from the Dior collection are on display in Lewes, alongside the images and works of Grant that helped inspire them. A hand-knitted sweater bears a design, featuring two female nudes, that Grant made for a curtain at a London theatre; a zip-up jacket features a lily-pond-like pattern that Grant painted on a table for the bedroom at Charleston used by John Maynard Keynes.

Jones’s Bloomsbury collection will eventually be bequeathed to Charleston, and he has acquired a defunct elementary school in Sussex which is to become a scholarly repository for books and manuscripts and other objects. For the moment, though, he lives with the collection in his homes, in Sussex and in London. In Sussex, Jones has hung up two male nudes by Grant, whose private erotic drawings of men were the focus of an exhibition at Charleston last year. In London, a spacious and elegant lavender-colored living room displays six Bloomsbury-era paintings along a single wall, among them a Post-Impressionist portrait by Grant of Vanessa Bell wearing an orange dress trimmed with green, with a yellow shawl over her head. The work was bought at auction in London last year for more than three hundred thousand pounds—a record high for Grant. Jones is lending it to the “Bring No Clothes” show, along with a number of other treasures, including the copy of “Orlando” inscribed to Sackville-West, which he bought a few years ago. Jones owns eleven copies of the novel, nine of them inscribed by the author to different members of the Bloomsbury group. “The book is more relevant now than it was when it came out, just shy of a hundred years ago,” Jones told me. “And it will probably speak even more to the generation a hundred years from now.”

“What a pity one can’t now and then change sexes!” Lytton Strachey once wrote to Clive Bell, adding, “I should love to be a dowager Countess.” To Strachey, Morrell once declared that she wished she were a man, “for then we should get on so wonderfully.” As Strachey’s biographer Michael Holroyd has observed, the two often did get on wonderfully, neither of them conforming to the prevailing expectations of masculinity and femininity. When Strachey came to stay at Garsington, he and Lady Ottoline enjoyed dipping into her wardrobe, treating its contents like a box of costumes. Morrell wrote of one visit, “At night Lytton would become gay and we would laugh and giggle and be foolish; sometimes he would put on a pair of my smart high-heeled shoes, which made him look like an Aubrey Beardsley drawing, very wicked.” (Beardsley, a contemporary of Morrell’s, was known for his erotic and disturbing pen-and-ink drawings, including illustrations of Oscar Wilde’s play “Salomé.”) Morrell wrote of Strachey, “I love to see him in my memory tottering and pirouetting round the room with feet looking so absurdly small, peeping in and out of his trousers, both of us so excited and happy, getting more and more fantastic and gay.”

In the “Bring No Clothes” book, Porter peers into the sometimes transparent, sometimes occluded queerness of several Bloomsbury figures. In a chapter on Keynes, who famously had a prodigious count of lovers, Porter turns his queer eye to the photographic record. He notes Keynes’s dominant stance when captured in conversation with his sometime partner Grant—left hand shoved into his pants pocket, pelvis tilted forward, shoulders back. “Keynes’s pose breaks with the respectfulness of the tailored suit,” Porter writes. “It says, I want more now. It also says, I claim power.” Porter finds another image of the pair taken a few years later to have similar body language: Keynes has his hands on his clearly irrepressible hips. Elsewhere, Porter writes with subtlety about Carrington’s efforts to find language for an identity that today might be categorized as nonbinary. In a 1925 letter rejecting a former lover, Gerald Brenan, Carrington tells him, “You know I have always hated being a woman. . . . I am continually depressed by my effeminacy.” Writing elsewhere of an affair with the American journalist Henrietta Bingham, Carrington confesses to having “a day-dream” of “not being female.” Porter’s book illuminates the ways in which gender norms, no less than norms of sexual orientation, were up for grabs among the Bloomsbury set, even while certain social conventions, including marriage, were observed. (Both Keynes and Carrington married partners of the opposite sex; Strachey was unusual in Bloomsbury circles for never marrying.)

Despite the assertion of Miranda Seymour, Morrell’s most recent biographer, that “lesbianism played no part in Ottoline’s life”—a judgment that echoes that of an earlier biographer, Sandra Jobson Darroch—Porter believes that there is ample reason to count Morrell among the queer women of Bloomsbury. In a well-known sequence of photographs taken in the gardens at Garsington in the summer of 1917, Carrington, then in her early twenties, climbs naked upon a muscular statue of a male figure, against whom her own athleticism is counterposed. Porter points out that Morrell was holding the camera. He includes a photograph of Morrell lying naked alongside a row of shrubs at Garsington, a trail of discarded clothes behind her. Morrell, twenty years Carrington’s senior, is lithe-limbed, with the slack belly of a woman who has borne children. The photographer is unknown, but Porter suggests that Morrell and Carrington exchanged the camera as they robed and disrobed.

Porter also advances a theory that Morrell and Virginia Woolf may have fleetingly been lovers. He cites, among other suggestive evidence, a remark in a letter to Vanessa Bell from Roger Fry, an art critic in the Bloomsbury group, that Morrell and Woolf “have fallen into each other’s arms.” At the very least, Porter argues, it makes sense to consider Woolf and Morrell as “queer comrades.” In an inspired bit of sleuthing, Porter considers a photograph of Woolf shot for Vogue in 1924, a year before the celebrated glove-holding portrait. Woolf is shown wearing a dress that is usually described as having belonged to her mother, Julia Stephen. Porter is skeptical: the dress’s style, he shows, does not resemble any garments known to have been worn by Stephen, who was much photographed, being a great beauty. Instead, Porter hazards, the dress, with its dramatically puffed sleeves and its low, lace-edged neckline, which gapes around Woolf’s slender collarbone as if it were several sizes too big for her, may have been loaned to the novelist by her friend Morrell: a token of affection, and perhaps more, passed between them.

As Morrell’s wardrobe was being studied, the garments betrayed other details about the Bloomsbury group and their friends, enemies, and supporters—scraps of their lives that have escaped the bonfire of time. When curators at the Fashion Museum in Bath peeked into the pockets of a pair of high-waisted, balloon-legged pants made from soft, indigo-colored cotton velvet, they found remnants of Ottoline’s cigarettes, perhaps left over from a walk in the countryside around Garsington.

Also on display in Lewes is a long black velvet tunic, embroidered with gold thread in geometric patterns, in a knockoff of a style popularized by the Spanish couturier Fortuny. Morrell may have been an aristocrat, but she was not as wealthy as she looked—financial pressures eventually forced her and Philip to sell Garsington—and she preferred to have her clothes made locally, rather than in the ateliers of Europe. Stitching irregularities suggest that the tunic was made by Morrell’s own dressmaker. The inside of the neckline is stained with an oily residue, probably from makeup. It looks like the dirty collar of a five-year-old who has hurriedly used her T-shirt to wipe her mouth—and therefore suggests the careless vivacity of the wearer, as an evening with friends grew more and more fantastic and gay.

Shortly before “Bring No Clothes” was installed in Lewes, Porter made a discovery about another Morrell garment that he’d selected for the show, a gauzy tunic of undyed linen, edged with ceramic beads. The front is patterned with eight repeating floral motifs outlined in dull green; some of the petals are colored in pale pink and blue. Porter researched the Fortuny archives and found that this garment was in fact genuine, except for one inauthentic detail: on the original, the floral pattern was printed without color.

Like Morrell’s puffed-sleeve velvet gown, the tunic had gone to the conservation studio in Battersea. When it was withdrawn from its tissue-lined box and carefully laid out on a worktable, Porter recalled something that he had been told earlier by a costume researcher named Gill MacGregor: the pink and blue on the fabric wasn’t evenly distributed. Unlike the green outlines, the petals seemed to have been colored in by hand. The tunic had been modified, embellished to suit the inclinations of Morrell, who—like so many of her guests, and friends, and lovers—saw no reason to adhere to the prescribed tastes of the time, in matters sartorial or otherwise.

It was impossible to say who had been responsible for the alteration. Most likely, the handiwork—like the irregular stitching elsewhere on Morrell’s clothes—was that of her dressmaker. But wasn’t it possible to imagine Morrell taking up a paintbrush on her own, just like the artists with whom she surrounded herself? Among the objects that survive her are several sewing boxes, filled with brightly colored thread. “She could make dresses herself—she talks about making dresses as a child,” Porter said. Even if there was no telltale paintbrush among the needles and bobbins, it was nonetheless tempting to believe that Morrell had made her mark, experiencing for herself the transcendent pleasure of creation. ♦

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.