“If a man looks at the world when he is 50 the same way he looked at it when he was 20 and it hasn’t changed, then he has wasted 30 years of his life.” — Muhammad Ali

One moment in Jay-Z’s recent interview with CBS’ Gayle King stood above the rest. The 24-time Grammy winner was speaking about his firstborn, Blue Ivy. Although Jay-Z is a master wordsmith, what he said wasn’t nearly as important as how he said it.

“I know her,” he said, referring to his daughter’s nervousness before performing on the Renaissance tour with her mother, Beyoncé.

On the surface, the quote doesn’t hold many — if any — ties to Jay-Z’s The Black Album, released 20 years ago on Tuesday. But for me, someone who has always found the evolution and contradictions of Jay-Z’s life beguiling, the connection lies in emotion.

Hip-hop is a genre where so many of its legends are marked by how old they were when they died. Tupac Shakur is still 25. Biggie Smalls is still 24. Nipsey Hussle will always be 33. Lisa “Left Eye” Lopes, 30. Mac Dre, 34. The list, unfortunately, goes on. Yet that pain, guilt and grief makes seeing artists grow older a gift.

With Jay-Z comes the balance of understanding who he was as an artist and man in 2003 and who he is in 2023. It makes listening to his music even more of a holistic experience.

Listening to The Black Album, the only things more apparent than Jay-Z’s lyrics were his intentions. By the fall/winter of 2003, Jay-Z was hell-bent on “retiring.” He had released an album every year since his 1996 debut, Reasonable Doubt. His star power rose with each project, peaking with The Blueprint in 2001. Yet, platinum albums, millions of records sold and a record label he helped build from the ground up weren’t enough.

“They say, ‘They never really miss you ’til you dead or you gone’ / So on that note, I’m leaving after this song,“ he rapped on “December 4th.”

“Pound for pound, I’m the best to ever come around here/ Excluding nobody, look what I embody,” he claimed on “What More Can I Say?” “The soul of a hustler, I really ran the street/ A CEO’s mind, that marketing plan was me.”

On “Encore,” Jay-Z rapped: “Who you gon’ find doper than him? / With no pen, just draw of inspiration / Soon you gonna see you can’t replace him / With cheap imitations for these generations.”

“Hov, oh, not D.O.C./ But similar to them letters, ‘No One Can Do It Better,’ ” he proclaimed on “Public Service Announcement,” which was produced by Just Blaze.

It wasn’t as much seeking validation as leaving no room for debate. That’s what motivated Jay-Z, at least musically, in 2003. After The Black Album came several life chapters integral to discussing Jay-Z’s impact on pop culture: the dissolution of Roc-A-Fella Records and his onetime friendship with label co-founder Damon Dash; the expansion of his entrepreneurial endeavors, including his role in bringing the New Jersey Nets to Brooklyn, New York (and the discussions around gentrification that came with it); and his relationship with Beyoncé that would eventually lead to marriage.

In a 1998 interview, Jay-Z spoke about how he viewed love and whether he was ever meant to find it. “The women I was with, I loved things about them. But I never been in love, because they say love is forever — and I never felt that forever-type of thing,” Jay-Z, 29 at the time, said. “I never been away from anyone and be like ‘I can’t wait to get back to ’em.’ I guard myself. I won’t allow myself, but I know that, so I’m on my way to recovery.”

In April 2003, seven months before The Black Album’s release, Jay-Z sat with Playboy for an interview on myriad topics, including the miscarriage a previous partner had experienced and how it was difficult for him to grieve. (He mentioned this on “4 Da Fam” by Amil Whitehead in 2000.) He took the tragedy as the universe telling him he “wasn’t ready to be a dad.” Jay-Z also spoke about the dating rumors swirling around him and Beyoncé. He said they were just friends, and if it came down to choosing her or his longtime homie Memphis Bleek, “Beyoncé’s got to go,” he said, laughting. His “paranoia about women” wasn’t as cynical as it once was, he said then. He said that being hard to read presented problems in personal relationships.

“I’m not the most ‘I-love-you’ guy. That’s one of my problems,” he said. “‘What you want me to tell you? Those are just words — everyone is going to tell. Look what I do.

“I have to change that,” he said.

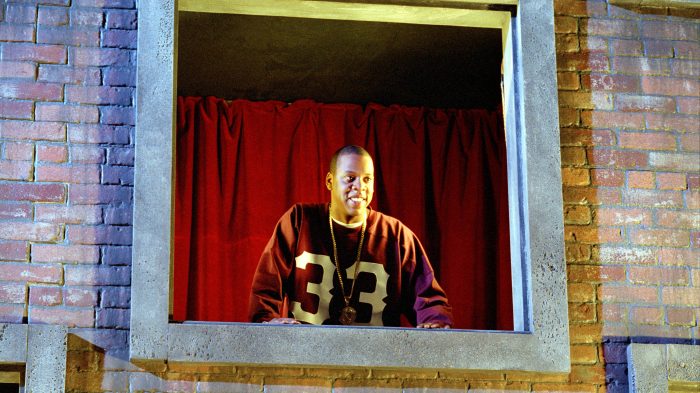

Kevin Mazur/Getty Images for Roc Nation

Jay-Z’s personal life has always unfolded on wax, or at least as much as he was comfortable revealing. From songs such as “Song Cry” (2001), “Lost One” (2006), up to his piercing 2017 album 4:44, where he admitted to infidelity in his marriage. He’s even referred to events such as the infamous elevator fiasco with him, Beyoncé and his sister-in-law Solange. The imprudence of his indiscretions, according to his music, nearly cost him his marriage. And that’s as much a part of Jay-Z’s story as anything else. The man who held the world in his hands nearly crumbled it with those same fingers.

The Black Album wasn’t a project focused on where Jay-Z saw his love life. There were levels of introspection on records such as “Moment of Clarity” (Pop died, didn’t cry, didn’t know him that well/ Between him doing heroin and me doing crack sales) or “What More Can I Say?” (I pray I’m forgiven/ For every bad decision I made/ Every sister I played / ‘Cause I’m still paranoid to this day/ And it’s nobody fault, I made the decisions I made / This is the life I chose or rather the life that chose me). He was still obsessed with standing on his own business. Money, power and respect were nonnegotiable. By 2003, he was less than a decade removed from selling crack. It made sense then, but in retrospect — much like anyone — he was far from the person seen now.

All of this is why the sit-down with King piqued my interest. The argument has already been made that the exhibit looking back on Jay-Z’s career, The Book of HOV, is self-serving — even if Jay-Z didn’t know anything about it as it was coming together, as he said in the interview with King. Yet, as he spoke on “the genius” of Beyoncé’s Renaissance tour and how much he enjoyed being a supportive partner at every stop, it was a reminder of how much a difference two decades can make.

Anxiety runs parallel with success. This is no different with Jay-Z. Throughout his life, he’s spoken about how anxiety has affected his career and how much he’s been able to truly enjoy his own success. He couldn’t have prepared himself to watch his daughter perform in front of nearly 100,000 people. Twenty years ago, Jay-Z was focused on ensuring those 100,000 fans knew he was the best at his profession. Now, it was all about making sure his daughter overcame her own fears.

“What makes me proud [of Blue],” Jay-Z said, “Blue’s been born into a life she didn’t ask for … So for her to be on stage and reclaim her power — and the song is called ‘My Power’ — you can’t write a better script. Then, watching her grow in it, it’s 80,000 people. She’s 11, so she’s nervous!”

“She didn’t look nervous!” King retorted.

“I know her,” Jay-Z said, pointing to his chest. “I know how nervous she was. I know how frightened she was.”

His voice had a deep level of pride as he spoke of how seriously she took training for the tour. Or how proud he was to know she asked him his thoughts on her fashion choices. This, in 2023, is what satisfaction looks like for Jay-Z. Not the money. Not the music, or even the thought of new solo music. For Jay-Z, like many parents, his kids’ victories carry a heavier weight than his own.

The greatest gift Jay-Z has ever been bestowed with isn’t the music he’s created. It isn’t the flow that landed him in the Songwriters Hall of Fame. It’s not even the massive financial portfolio. The greatest gift Jay-Z has received is life.

Jay-Z, speaking reverently of his wife and kids throughout the interview with King, called to mind a memory from “Allure” 20 years earlier. The track is more of a trip back to when Jay-Z risked life and limb in the streets. Every day, every transaction was one step closer to the financial freedom he coveted — but also a prison cell or graveyard. Rap was but a pipe dream. “I never felt more alive than riding shotgun / In Klein’s green five until the cops pulled guns,” he reflected on the album. “And I tried to smoke weed to give me the fix I need / What the game did to my pulse with no results.”

That’s a hard truth about street life. Users use — and sellers sell. Either way, you’re exchanging part of your soul for a high that will never be as glamorous as the pursuit of it. How often Jay-Z thinks about life is a question best left for Jay-Z. The close calls with the police. The even closer calls in the streets. And the lives lost in those streets.

With Jay-Z, there is enough criticism to last for years and praises to travel even longer. Perhaps somewhere in the middle is the truth — about the man and our own experiences with him. The Black Album is a time stamp of an album and of a man who had no way of knowing where the universe would take him. His most recent interview is a case study of a man we’ll never know everything about. Yet, at 54, Jay-Z, in his own way and contrary to what he rapped, has never looked more alive. His pulse has never yielded a more definitive result when living life for someone beyond himself.

All he had to do was survive.

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.