CNN

—

Chanel’s 1991 Fall-Winter ready-to-wear show was set in Paris, but its soul was right off the streets of New York City.

A remix of Nancy Sinatra’s “These Boots Are Made for Walkin’” blared overhead as one thousand or so spectators, like “Rocky” actors Sylvester Stallone and Dolph Lundgren, gazed at leggy models in bold and provocative silhouettes: Karen Mulder in a black leather trench, her waist circled by layers of gold rope chains that created a shimmying hula skirt, Helena Christensen in a see-through black mesh bodysuit, her décolletage perfectly accented by long Cuban links. Supermodel Linda Evangelista wore a gold baseball cap, tilted to the back with attitude. Her famous physique was draped in a royal-blue jacket, but it was the extravagant accessories that took center stage: a cascade of gold chains adorned her neck, including a large nameplate emblazoned with the word “CHANEL.”

Streetwear, kitsch, and glitz collided in a smorgasbord of delicious excess on the runway. There were leather baseball caps worn backward, jackets with “Chanel” scripted across the back in pearls, distressed and ripped denim, and quilted jackets that would be as at home on 125th Street in Harlem as on the Champs-Élysées. Jeans added a youthful edge, while risqué catsuits and nipple covers, made from the House’s Camellia roses, kept things a little bit naughty. Silhouettes traditionally associated with Chanel’s aristocratic lineage, like the iconic tweed jacket and chiffon dresses, were updated and offset by hip-hop-inspired bling — chains, medallions, earrings, and bracelets — piled high atop each other.

“It’s the ‘nouveau’ rapper look,” said Karl Lagerfeld of his vision. The designer became Chanel’s creative director in 1983 and held the role until he died in 2019. His tenure was that of a consummate chameleon, evolving and giving zero f*cks in the process. An avid student of the zeitgeist, he leaned on diverse source material in creating his visions. “I think what Lagerfeld has always done amazingly well is completely capturing the mood of the moment,” said Tim Blanks, editor-at-large at Style, in a 2014 retrospective of the nouveau rapper show. “He listens to everything, reads everything, sees everything, and then distills it into these potent fashion images.”

What would become known colloquially as Chanel’s “hip-hop collection” was a watershed moment, the pinnacle of French prêt-à-porter (ready-to-wear) welcoming hip-hop into its sanctum. “Lagerfeld is deliberately provocative,” observed Vogue, “taking his Chanel show to the edge of an abyss of kitsch and funk.” “It’s young, colorful, taken right from the street fashion scene,” gushed Rose Marie Bravo, chief executive at the historic I. Magnin & Co. department store at the time.

(Not everyone was a fan of Chanel remixing its classic French heritage with the now. The core clientele invested in Chanel because they knew they were getting timeless classics and staple pieces. “How many women are going to wear a silver catsuit?” complained a retailer during a preview of the collection.)

Despite his reverence for the house of the double Cs, Lagerfeld was his own visionary. “The idea that Chanel should be respected and never touched again is a joke,” he said. “I have no respect for anything. In fashion, you have to be rough and tough. In every decade, there is a way to put Chanel back on the fashion map.” His vigor kept the brand relevant. Lagerfeld was the consummate multihyphenate. He was the personification of the brand but also utilized his creative skills as a photographer and started shooting the house’s fashion ads in 1987. This would be no different than when rappers would begin to own clothing lines and were required to be the master of many functions: creative visionary, model, and evangelist.

Chanel was the ultimate European luxury cosign, but innovative designers on both sides of the pond were taking notice of hip-hop in the early ’90s: In April 1991, Women’s Wear Daily featured a cover celebrating the “Rap Attack” with American designers Isaac Mizrahi, Charlotte Neuville, Adrienne Vittadini, Randolph Duke, and Norma Kamali. W Magazine and Newsweek followed suit, running features and using racially coded terms to describe the trend.

Brits Katharine Hamnett and Rifat Ozbek showed collections with sneakers and tracksuits à la LL Cool J, oversized hoodies, and Afro-centric prints similar to those worn at the time by Queen Latifah or A Tribe Called Quest. Donna Karan, who launched her more affordable, youth-centric DKNY line in 1989, showed gold bodysuits and zippered accents.

“The most stylish people are the homegirls and homeboys,” said American designer Isaac Mizrahi in an interview with Women’s Wear Daily.

It’s unclear whether Mizrahi and the like appreciated hip-hop or saw it as a grab for cache and cash. “Every era and every time has something of an undercurrent of some ethnic culture that influences it and gives it movement and currency,” Mizrahi said at the time. Culture was a holistic concept and parsing it into its “cool” elements without regard for the Black and brown people that made it was all too convenient. “We had to look to the Black cultures to give us some clues about style,” said Mizrahi. “We take these styles, refine them, give the customers as much a dose as they can deal with and bring a little funk into their lives.”

There was understandable hesitancy from hip-hop and Black fashion critics on whether the trend was celebratory or parasitic. “The designers are way off the mark,” said Fab 5 Freddy, host of “Yo! MTV Raps,” in 1991. “These styles don’t reflect what’s on the street anymore.” If history proved anything, once the powers that be sucked up counterculture and regurgitated it to the masses, it immediately lost any semblance of cool.

“When Black kids were wearing a lot of gold chains, they were condemned by society,” said Denise Burrows, a buyer for Ebony Fashion Fair, the historic traveling runway show featuring iconic African American models like Pat Cleveland and Dorothy “Terri” Springer that began in 1958. “But then Lagerfeld does the same thing for rich women, and he is applauded. There is a double standard here.”

The New York Times was brutal to the 1991 shows in New York City: “Rap street style, with its jumble of jewelry and tongue-in-cheek references to high fashion — for example, street-peddler Gucci and Louis Vuitton shirts, caps, and belt packs — is already a form of fashion self-mockery. On the runway, it’s a joke on top of a joke.” There was a bias, implicit or otherwise. The establishment of predominantly older and white critics viewed hip-hop as gauche, a caricature, beneath their high standards. Rappers were in costumes and not fashion.

Bad timing or not, hip-hop style was officially gentrified. This tension, the constant push and pull of the old guard playing on a new block, was only just beginning. And just like any neighborhood undergoing a transition, the originators would collide with the transplants. The turf wars had just started.

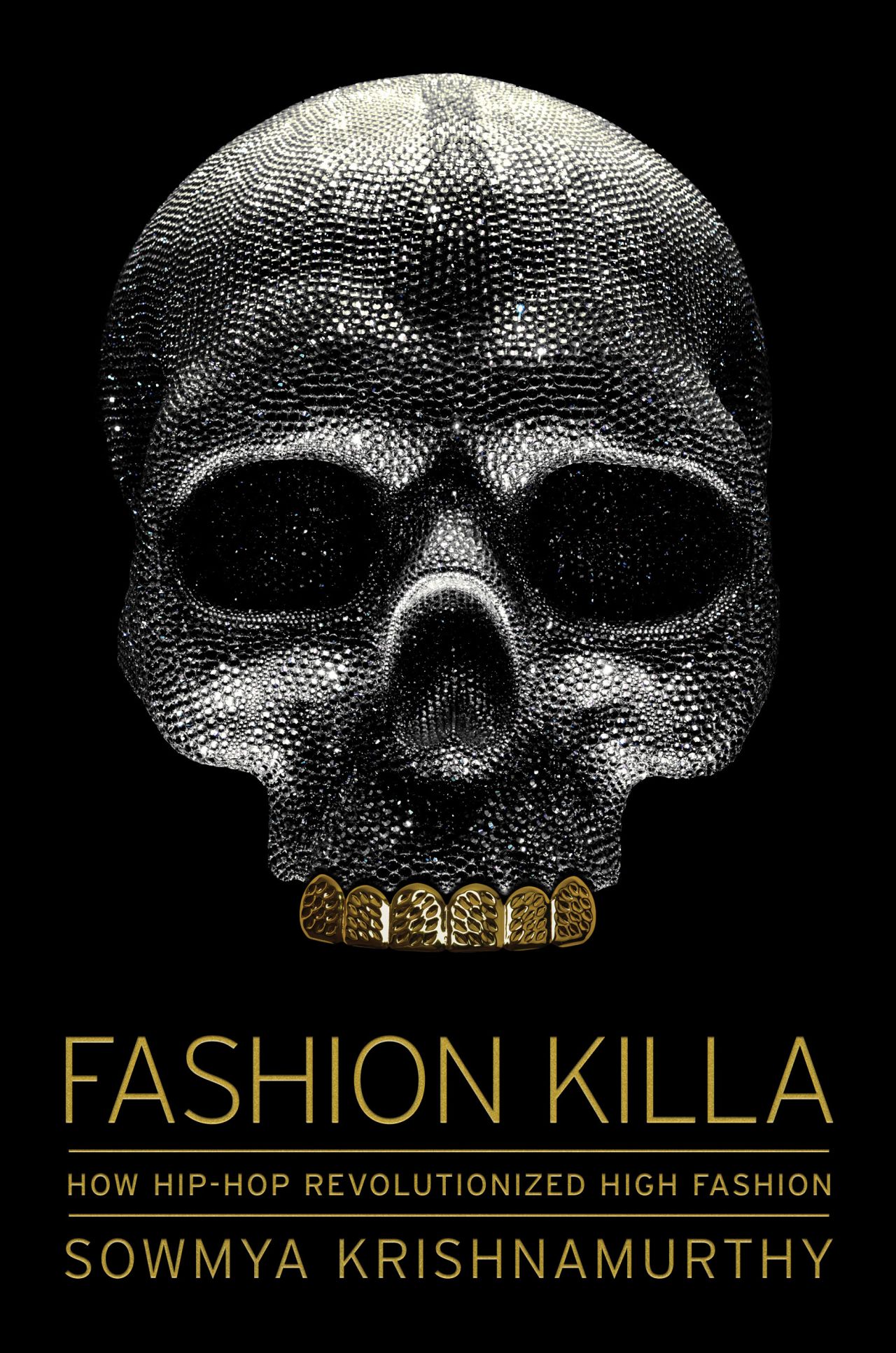

Editor’s Note: This piece is excerpted from Sowmya Krishnamurthy’s “FASHION KILLA: How Hip-Hop Revolutionized High Fashion,” published by Gallery Books, a subsidiary of Simon & Schuster.

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.