Some paintings become so iconic that it is difficult to remember that they are in fact paintings, not just posters on the walls of dorm rooms stained with Blu-Tack. Gustav Klimt’s The Kiss is a prime example. Because we encounter it most often in tattered poster form, or on mugs or keychains or some other kind of tat, it has ascended (or descended) into a realm entirely unrelated to the context in which it was made.

The painting is getting a deeper look in Klimt & The Kiss. The film – the latest in the Exhibition on Screen series – blends beautiful footage of the painting and its setting in the Belvedere Museum in Vienna with insightful criticism from curators and scholars to bring the artwork to life. There is a lot to unpack.

The painting is “a monument to a particular act,” says Ivan Ristić, curator at the Leopold Museum in Vienna. But questions lurk just under the surface: “Who is it that really wants this? What is the fate of this love? If it even is love?” Ristić asks us. It’s a strange scene. At first glance it seems romantic and joyful, but the longer you look, the darker it gets.

The subjects of the painting, dripping in molten gold, are two figures entwined. The male figure clasps the female figure around the neck and kisses her cheek, his own face invisible to the viewer. The female figure’s eyes are closed and she has a strangely blank expression. Her hands drape around his neck and clutch at his hand at her throat. She kneels on the ground in a meadow full of flowers, with her bare feet drifting off the edge of the ground towards an unknown abyss. Stephanie Auer, curator at the Belvedere Museum, points out that the man’s golden body is decorated with rectangular shapes, and the woman’s with curving shapes, in a clear delineation of classic masculine and feminine forms.

There is something domineering and violent about the male figure’s embrace, and something powerless, desperate, almost pathetic about the woman. Is she unconscious or are her eyes closed in bliss? Is she returning the man’s embrace or trying to claw his hands away? Many possible narratives have been mapped on to the scene by scholars and viewers. Some of those featured in the film read the painting as a depiction of the allegory of love, or of the Greek mythological story of Ariadne and Dionysus.

Others read the painting as a depiction of the artist himself and his muse, Emilie Flöge. Klimt and Flöge became close in 1892, when Klimt was 30 and Flöge 18. Flöge became a successful fashion designer and dressmaker, moving in chic Bohemian circles in Vienna with Klimt. Klimt left her half his estate in his will, although the two never married. Like many historical relationships, theirs remains sexually ambiguous. Klimt is known to have been sexually involved with many of his models and portrait sitters, but Flöge was a constant partner throughout his life and some believe their relationship was platonic. Perhaps The Kiss was an imagined scene of their love made corporeal, or perhaps it was a depiction of their real-life erotic partnership.

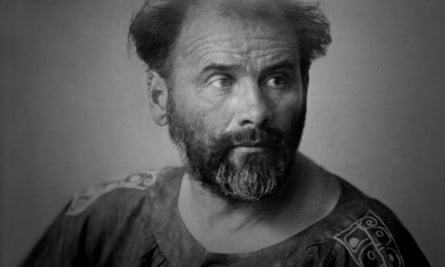

Though this work has become symbolic of Klimt’s style, he did not always paint in such a stylised, gilded way. Born in 1862 to a lower class family in Vienna, Gustav and his brothers Georg and Ernst all pursed careers as artists, with their parents’ support. Klimt studied at the University of Applied Arts in Vienna from 1876 to 1883, where he was given a traditional academic training. His first commissions after leaving university were a series of large murals in the newly constructed buildings of the Ringstrasse, the grand boulevard built between the 1860s and 1890s in Vienna that defined the city’s 19th-century ethos. As the film highlights, the final and decadent decades of the Habsburg empire in Austria were characterised by glamour and artistic flourishing as well as extreme wealth inequality. For all the grandeur of the Ringstrasse and the Viennese court, darkness and depravity lurked just beneath the surface.

Having successfully established his name with these high-profile commissions, Klimt became one of the most in-demand portraitists in Vienna. But around the mid 1890s, Klimt had what Belvedere curator Dr Franz Smola calls a “sudden creative crisis”. He changed his style completely, to become the artist that we recognise today. He became the first president of the avant garde Vienna secession movement, which was officially founded in 1897 by a group of artists, designers and architects who rejected the official Vienna Academy of Arts and the restraints of academic art. Their mantra was: “To every age its art and to art its freedom.” They celebrated natural forms and sought a totally immersive artwork, overlapping significantly with the art nouveau movement.

They built the Secession Building as a physical manifestation of their ethos and as an exhibition space, where they held shows several times a year. The most famous of these is the 1902 exhibition dedicated to Beethoven, for which Klimt made his famous Beethoven Frieze. The work is based on Beethoven’s 9th Symphony, the Ode to Joy, and uses an image of a man and woman embracing as the culmination of the journey to joy.

Klimt’s obsession with eroticism is visible throughout his work, including in the Beethoven Frieze and in The Kiss. His own sexual promiscuity was famous – he fathered at least 14 children. He liked to pull poor young women off the street and bring them into his studio to draw them nude, sometimes bringing several at once and encouraging them to perform sexual acts with each other while he drew.

after newsletter promotion

In the film, scholars and curators are divided about how to read this aspect of Klimt’s life. Baris Alakus, managing director of the Klimt Villa, criticises the way he used women of different classes for different ends, so that “he had a woman for every situation”. Auer notes that the homosexual acts he drew his working-class models engaged in were illegal in Vienna at the time, demonstrating Klimt’s disregard for their safety and respectability. But art historian Patrick Bade sees it differently. “Women liked him and he liked women,” he says, echoing a refrain commonly used to downplay the culpability of womanisers. Dr Marian Bisanz-Prakken argues that he celebrated “sacred” female eroticism. Yet Klimt’s practices strike me as domineering male voyeurism and sexual abuse. His disdain for women’s interior lives and fascination with their bodies is so pronounced it is almost a caricature of misogyny. Many of his paintings treat women as decorative, just like his elaborate gilded backgrounds and dresses, or as sexual objects.

Like many modernist male artists, Klimt’s attitude towards women is central to his art. It complicates his work and sits uncomfortably with 21st-century viewers. We still seem to fumble for language to respond to this discomfort, which arises more and more often as we revisit the work of historical artists. The film dwells on that discomfort, allowing viewers to hear various opinions and draw their own conclusions about Klimt’s relationship with women. It leaves space for tension and paradox.

Conversations around difficult art and artists often veer too quickly into the realm of “cancelling”. But it is impossible to cancel this painting, and Klimt’s works form the backbone of many Viennese museum collections. I think we should introduce skepticism into the way we look at his works. Klimt & The Kiss prompts viewers to begin to ask substantive, challenging questions. Why is The Kiss celebrated as a romantic painting, when the body language of its figures is so enigmatic and disturbing? What hierarchies and value systems does a painting like this uphold? Looking at a piece of art with a critical eye does not mean discounting it or rejecting its quality. It adds to our ability to appreciate and critique art to understand its context, however fraught. Holding the many truths and uncertainties about The Kiss at once makes the experience of looking at it, either on the wall at the Belvedere or on the wall of your bedroom, rather more interesting – and certainly more accurate.

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.