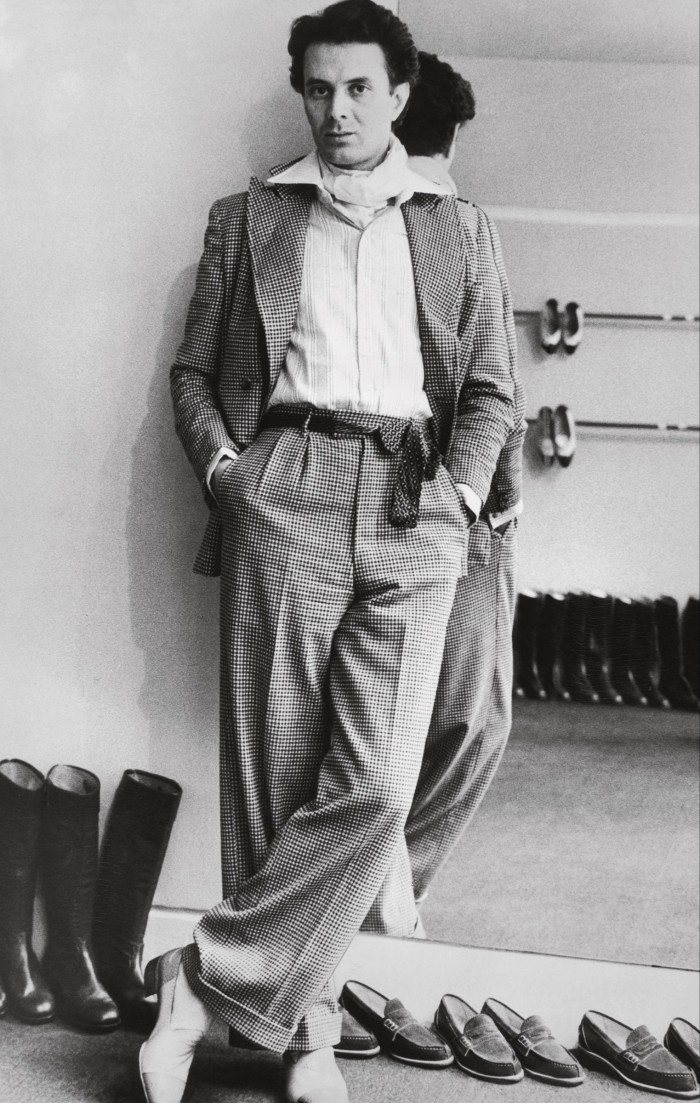

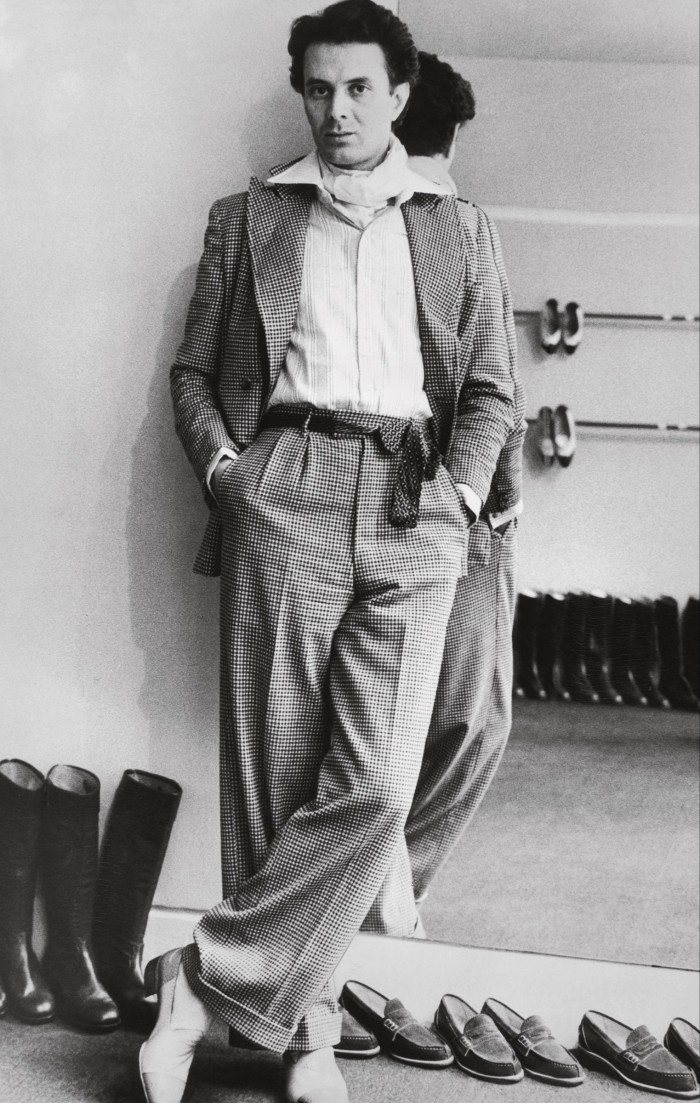

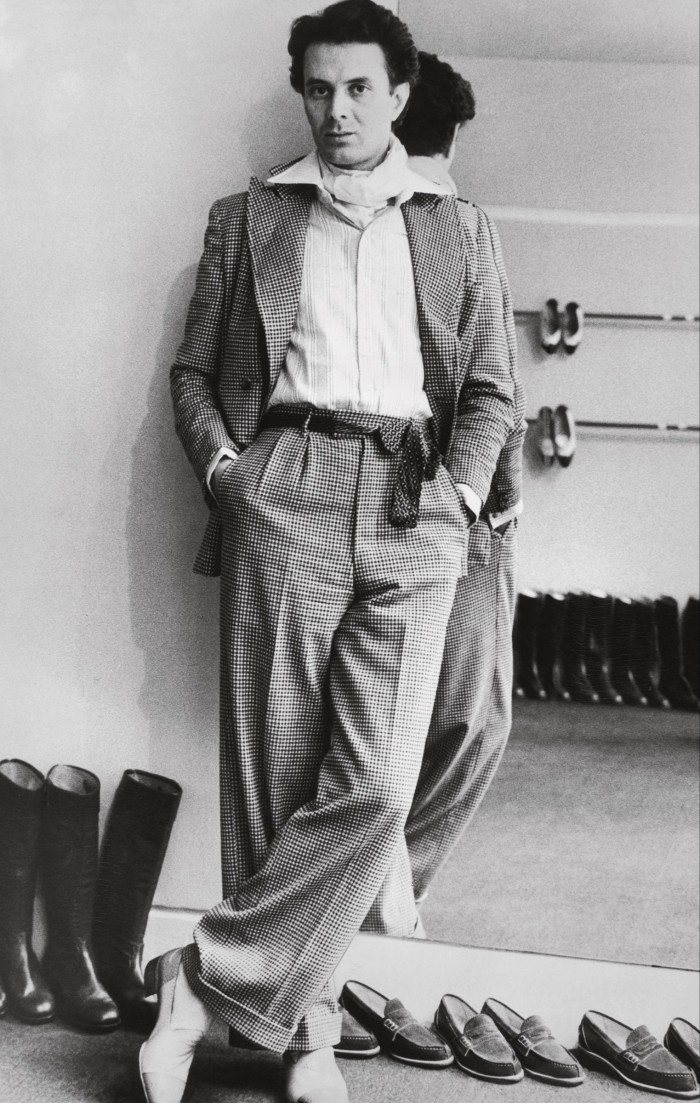

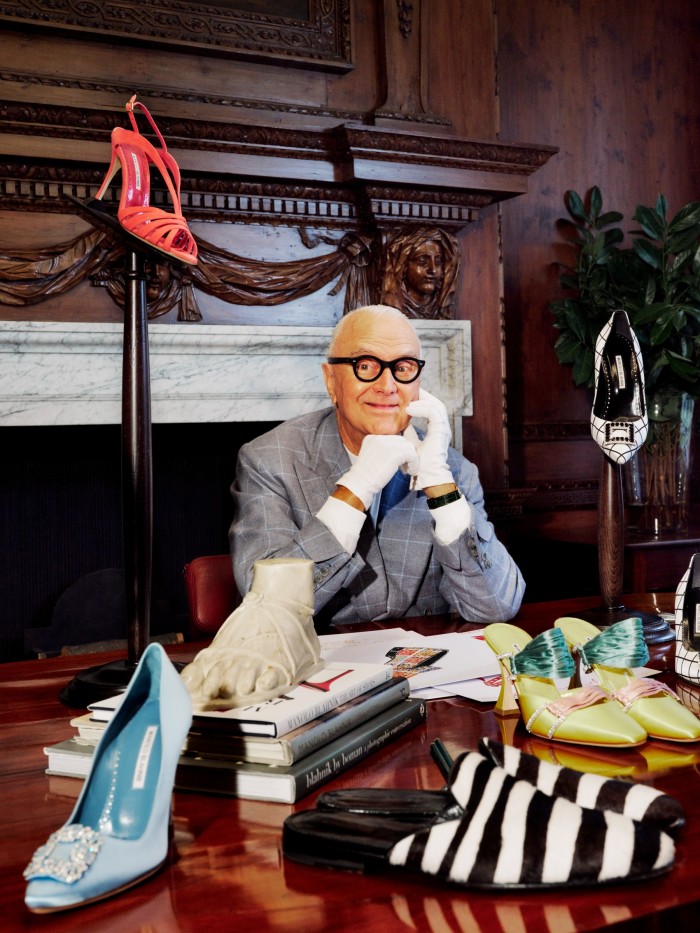

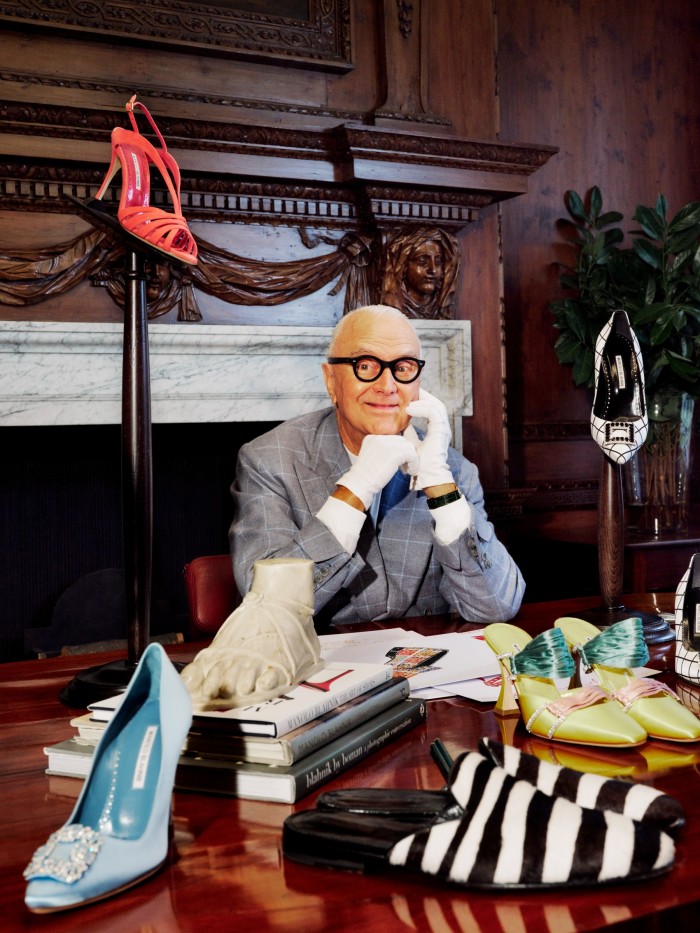

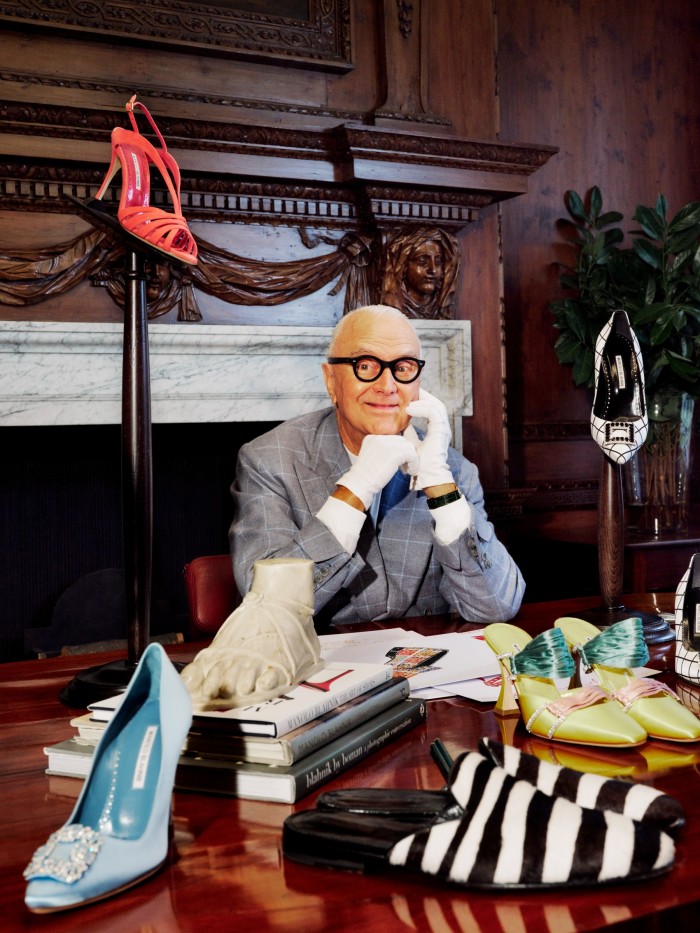

Manolo Blahnik advances, stately, into the room, decked out immaculately as per: the pale-blue checked suit is Anderson & Sheppard, the signature circular glasses are Cutler and Gross and the natty brown leather slippers are, of course, his own. The hair, white as porcelain – he’ll be 81 this month – is delicately coiffed. Most of the time we’re surprised to find famous people are small; the designer is tall, looming large even if leaning on a cane. He’ll protest at various points that his suit and his glasses are “filthy”, but they look pristine. Then again, who sees things like Blahnik?

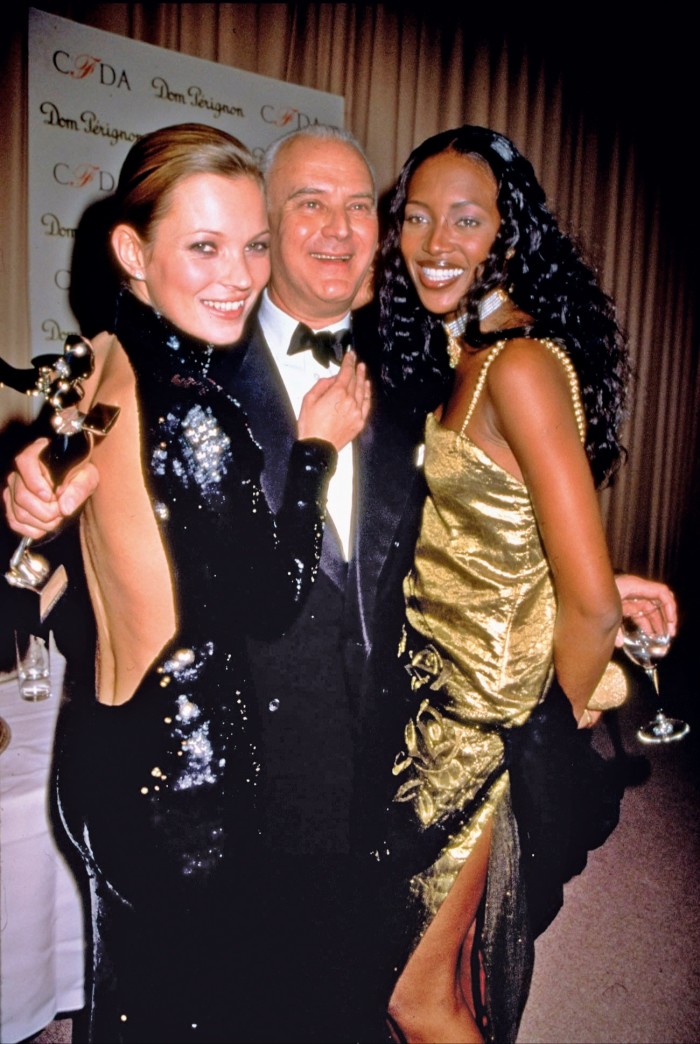

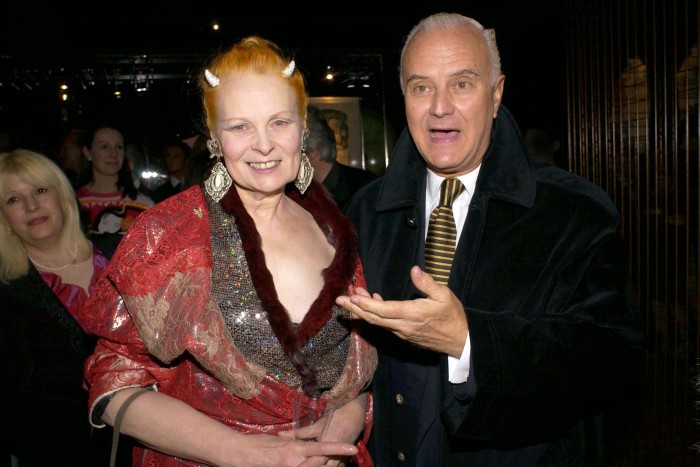

Manuel Blahnik Rodríguez has achieved the type of fashion immortality where even his childhood nickname is a noun. Generations of women (and men) adore his sleek, glamorous pumps, not least Carrie Bradshaw. Isabella Blow owned 120 pairs; Anna Wintour swears by his Callasli style – which he tailored to her inevitable specifications (she wanted a slingback added). Bianca Jagger, Anjelica Huston, Paloma Picasso, Diana Vreeland – who advised him to design shoes in the first place – have each added to his cult.

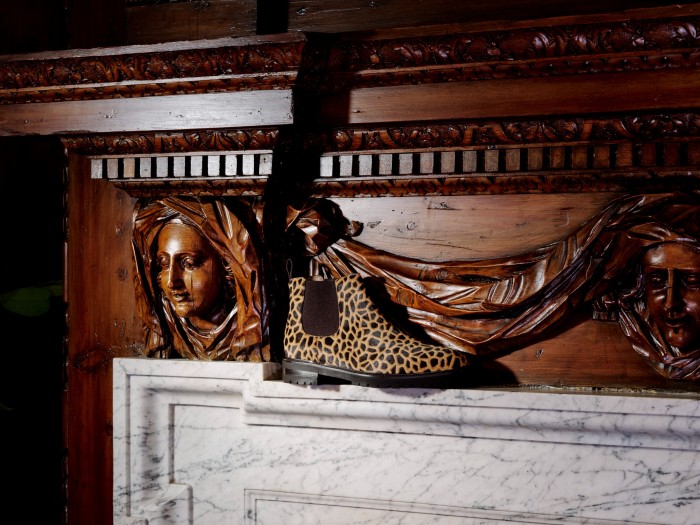

Blahnik sits down in a meeting room of his new London HQ, in front of an ornate fireplace topped by an 18th-century portrait of a white hound. “I met a wonderful girl in New York called Karlie Kloss – have you ever heard of her?” he asks, the accent of his native Canary Islands still strong but rounded by a certain RP formality. He is Mr Blahnik, I am Mr Wise. “I adore her, she’s a great customer. And then we have people like Hailey Bieber. All those girls, they’re buying my stuff now. My goodness, I never expected to last a long time, but I did. You know why? Because I love what I do.”

Blahnik opened his first boutique in 1971, on Old Church Street in Chelsea. It still exists today – a tiny, chic outpost based quietly off the King’s Road. He has 19 standalone stores and 250 “doors” across 22 countries, and 250 employees. “As long as some people like what I do, I’m very happy.”

A determined, quixotic talker, Blahnik takes each question and runs away with it, spinning you through the annals of his very crowded mind. The great photographer Irving Penn, taking his portrait, got him to relax by telling him to think of the Spanish mystic nun St Teresa de Ávila (Blahnik has all of her memoirs). He is charming and contradictory, often damning but somehow sweet. Even if he once told a newspaper that “relationships for me are a no-no”, even if he says that he prefers his dozens of pet dogs to people, he is still a great romantic, always seeking enchantment in books, films – and of course his shoes. “Mr Wise, you must be tired of my vomiting nonsense,” he says at one point. No, no, I say, but if you’re feeling tired we can always postpo– “No, no, I’m never tired of talking. Are you kidding?”

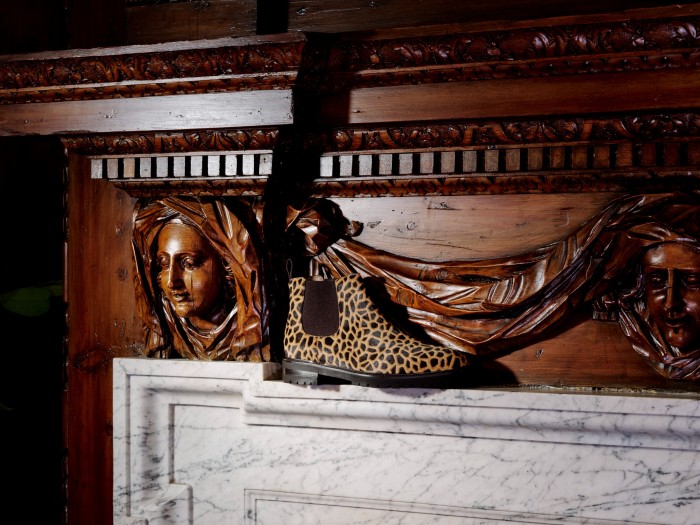

We are assembled to celebrate a few things. First, the move of the brand into No 31 Old Burlington Street. Long having had a base around the corner on Vigo Street, Blahnik has sunk “all his savings” in a beautiful townhouse built in 1718 by Lord Burlington, one of the fathers of British Palladianism, supposedly a gift for his lover. Blahnik loves the house, which is a relief as he bought it sight unseen; he was in the Canaries at his family home (he also has a home in Bath). It will serve as a headquarters for Blahnik’s operation, with an office where he can keep drawing his elegant designs, as he has done for more than 50 years. “I saw the pictures and I knew immediately: yes! There’s a horrible building next to it, but never mind…”

Next, we are marking a personal comeback after a difficult few years. In 2018 he caught pneumonia, which damaged his lungs. Later he fell down the stairs from the first floor of his British home, breaking his clavicle, his legs and more. “I could have died – I’m a very lucky person,” he says. “It’s been pretty devastating – especially for me, as I’m very active and need action all the time. But I’m starting to feel myself again.”

Finally, it’s a moment to toast the fact that Manolo Blahnik Group is in rude health. Last month it announced that 2022 was a record financial year, with sales exceeding €100mn for the first time: €118.2mn, up 69 per cent from €69.9mn in 2021. Kristina Blahnik, Manolo’s niece and CEO of the company since 2013, explains that this was in part due to the release of “a year and a half of pent-up glamour”, due to the events of 2020-21; a year of full sales at the brand’s Madison Avenue and East Hamptons stores, which both opened in summer 2021; and a significant push in menswear. The company views itself as an “investment brand” rather than a fashion one, she says. “We’re the jewellers of shoes, in many ways.”

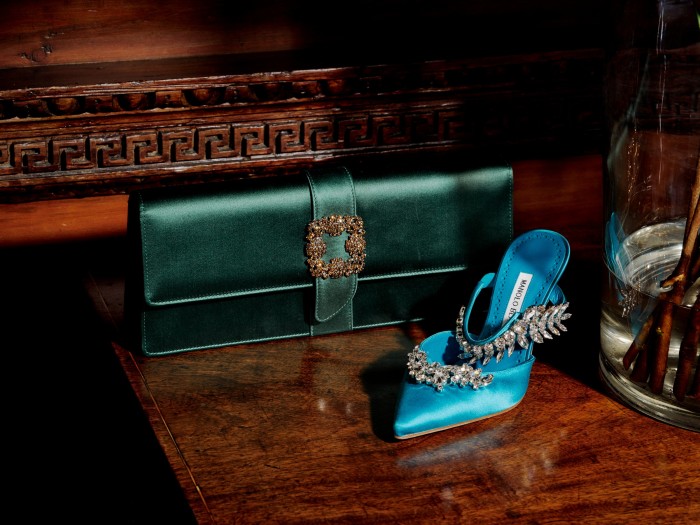

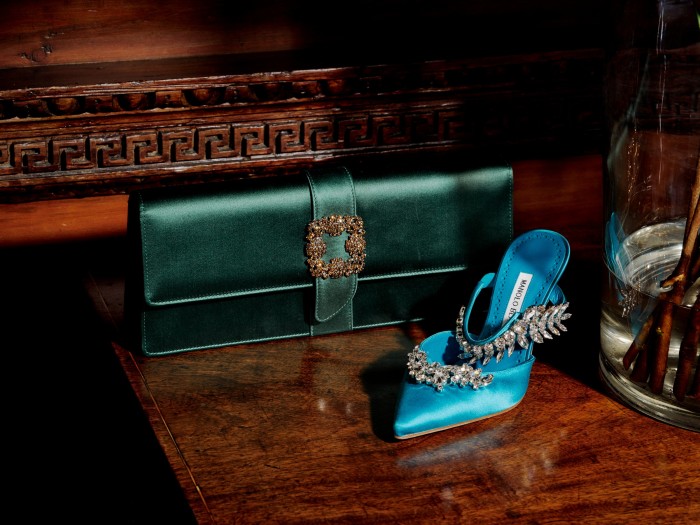

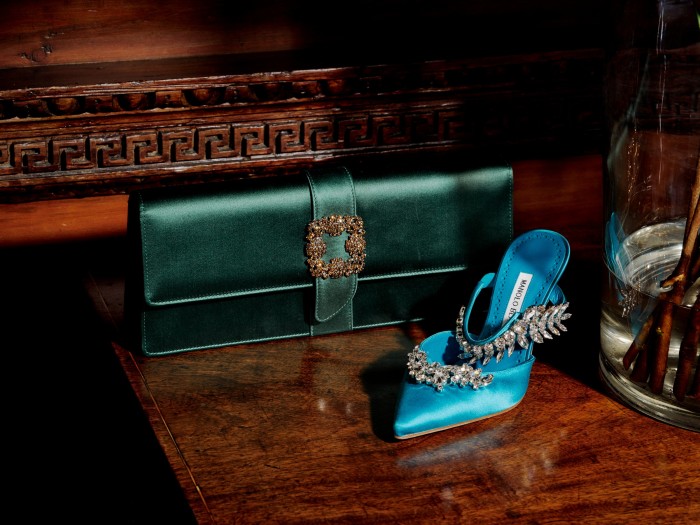

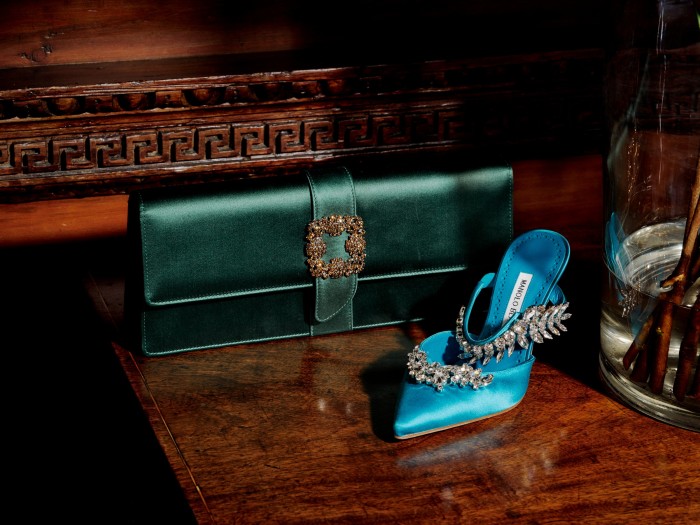

Hit models included the Hangisi (from £845), a classic satin Manolo pump with a glittering crystal buckle, the Maysale, a more demure take (from £595), and even a hit collaboration with Birkenstock (£330). Such a pairing might have seemed anathema once, podiatric chalk and cheese, but Blahnik has always kept up with the times (a few years ago, he did hit collections with Rihanna). “People say: why wear sandals? If you have ugly feet, with bunions, I don’t advise it – but if you have manicured, very clean footsies, it’s great.” (Side note: he once pronounced on pedicures to say that toenails should be painted red or natural, nothing else. HTSI’s Jo Ellison has never wavered from his edict: “Manolo speaks the truth.”)

Meanwhile he continues to be the runway shoemaker of choice for all kinds of designers, from Julie de Libran to Grace Wales Bonner. “I love Manolo’s shoes because they are recognisable but at the same time completely timeless and extremely comfortable,” says de Libran. “Perhaps the most comfortable, as it’s the same for a stiletto 11cm heel or a flat boot. The materials used are always researched and of beautiful quality. I love that it is a family brand, still completely independent.”

Blahnik works tirelessly every day. His daily phone calls are legendary (ask one of his publicists). Now that he is feeling better, he is looking forward to visiting his factories in person again. “Zoom – I’m so sick of Zoom,” he says. “People say, ‘You can do everything digitally.’ No, you cannot.”

Blahnik was born in Santa Cruz de La Palma in November 1942; his Spanish mother’s family owned a banana plantation in the Canaries, while his Czech father, a businessman, had taken refuge there to avoid the rise of fascism. The Blahnik home was distinctly Anglophile, not least because Winston Churchill was, to Blahnik’s father, “like God – he saved Europe”. The young Manolo grew up reading Enid Blyton, Kipling, Dickens and Wilde. His mother was a fastidious shopper, ordering clothes, magazines and books from abroad. “It took months to arrive – it was exciting,” he says. “We used to get things like Harper’s Bazaar – and this gave me an idea of what elegance and beauty used to be.”

Among her orders, from Harrods or Le Bon Marché, would be pairs of Start-Rite shoes that he would wear assiduously until he outgrew them. He has always loved shoes – “always, always”, he says. “I have a picture of myself, in fact, as a child, completely nude, holding a shoe.” (He would supposedly fashion tiny shoes from tin foil for the local iguanas, a story that is as adorable as it is apocryphal.) He still has those old Start-Rites at home – looking at them reminds him of an event or a person. “It’s very important for me,” he points out. “Not everybody thinks that way.” And yet, he says, “I never thought about making them.”

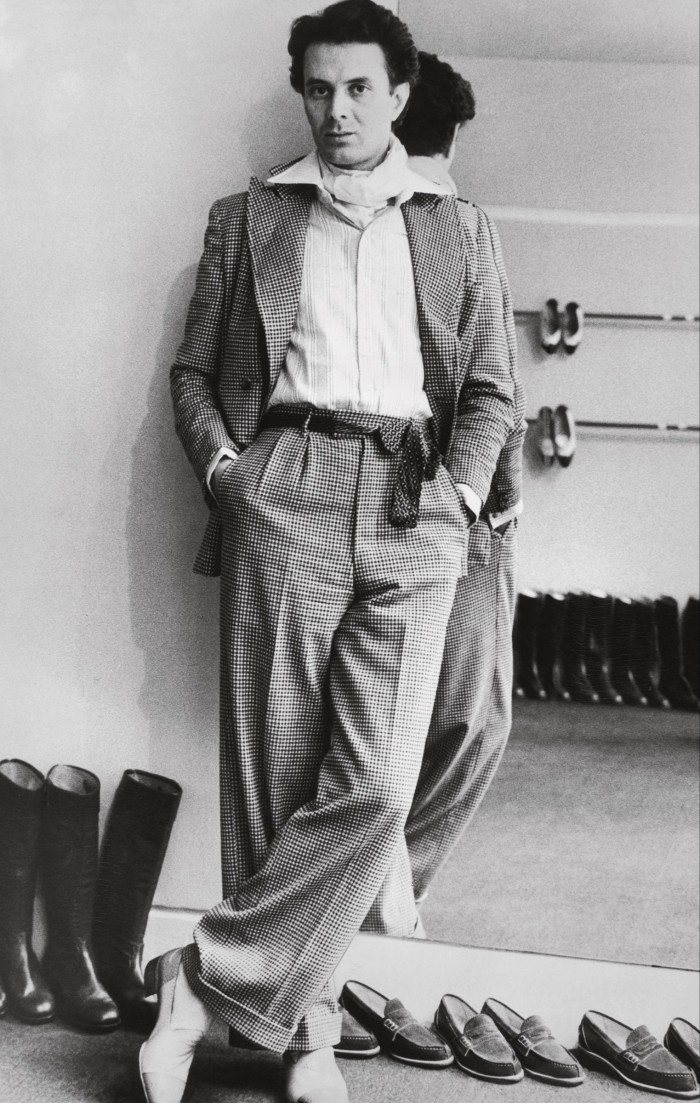

Instead, he went to university in Geneva to study politics and law – but soon switched to literature and architecture, then headed to Paris to study art and set design before moving to London in 1969. It was around then too that he had his mythic encounter with Vreeland, then editor-in-chief of US Vogue, who appraised his design portfolio, eyed him squarely and told him he should be making shoes. He started out doing men’s (for around 15 guineas a pair) but soon began making women’s too. It was a small operation, and the shoes were expensive, but “the people came back”, he says, “because the shoes didn’t disappear in seconds”.

“I remember buying my first-ever Manolo Blahniks in 1979, when I spent my entire university grant on a pair of burnt-orange beige suede pixie boots,” says his friend the milliner Stephen Jones. “I lived off baked beans for the rest of the term but it was completely worth every penny.”

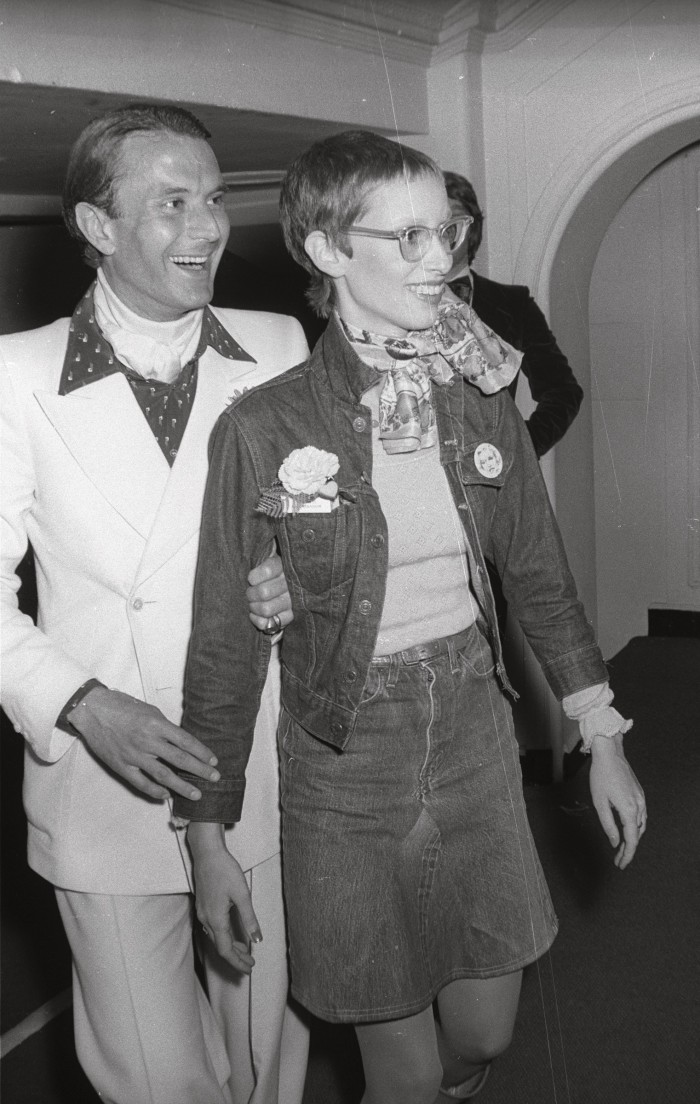

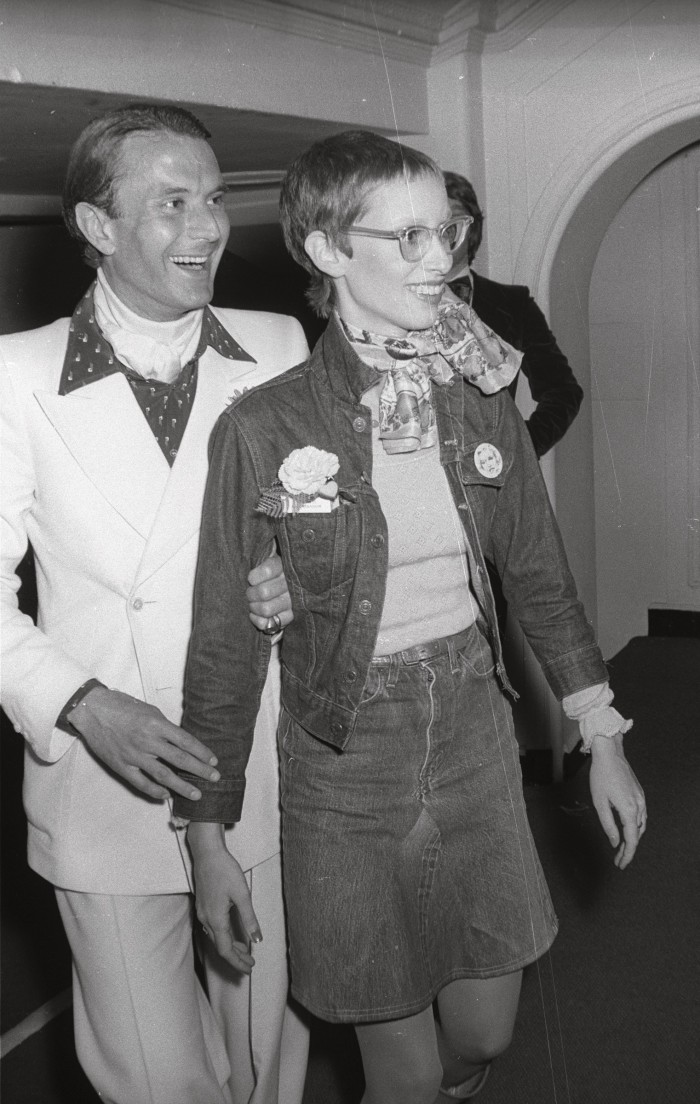

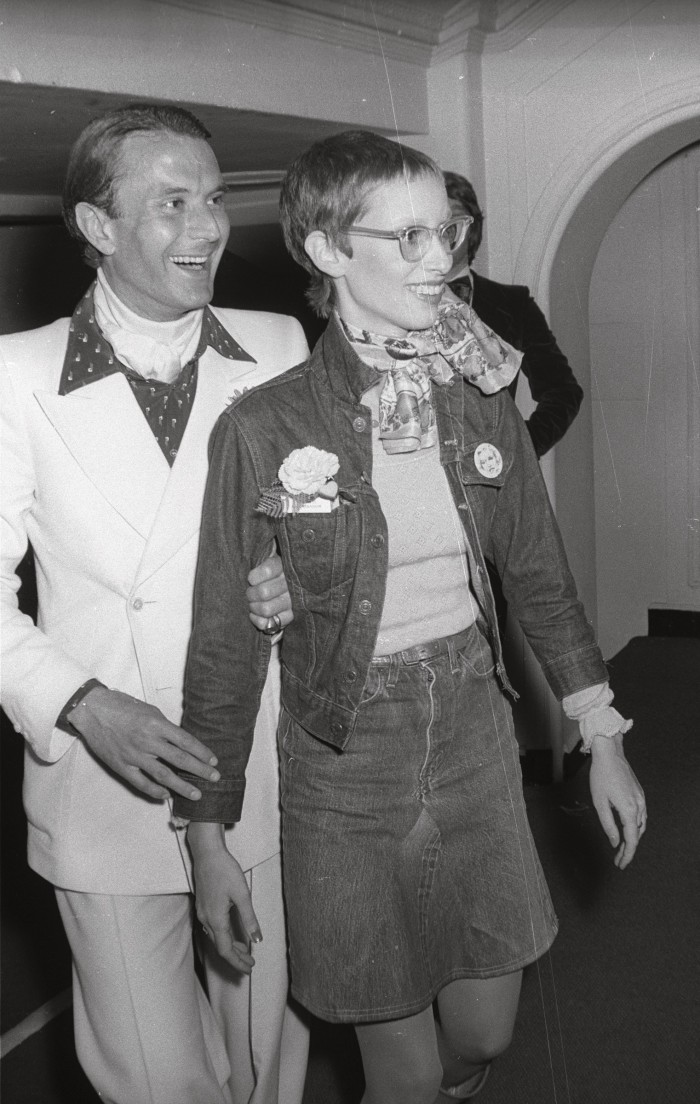

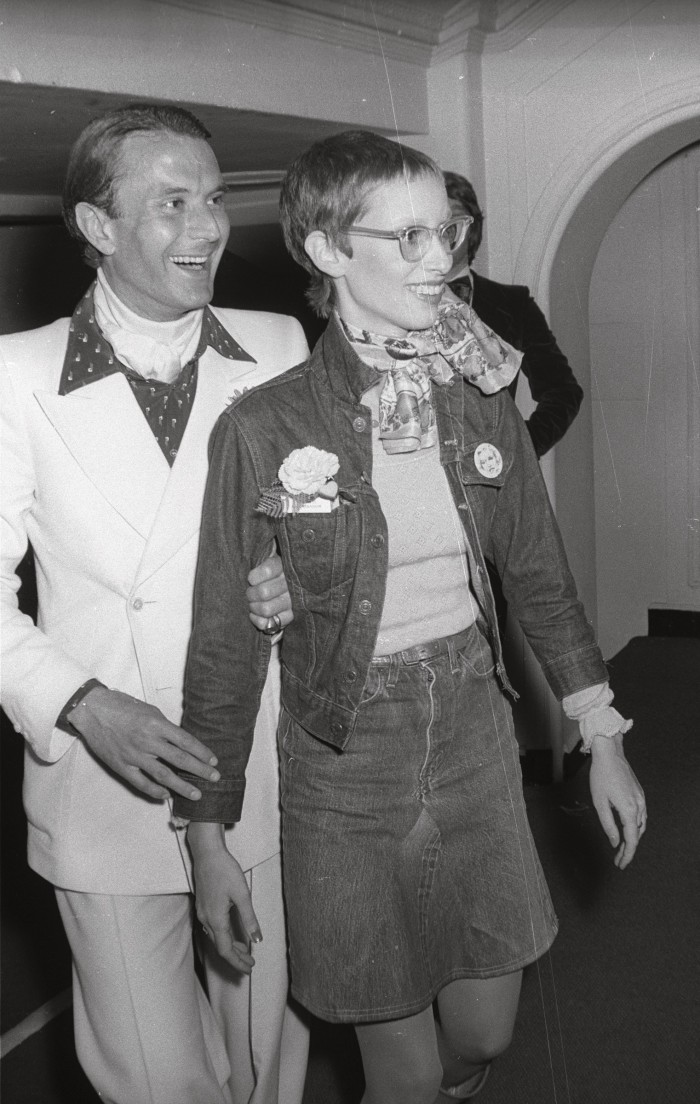

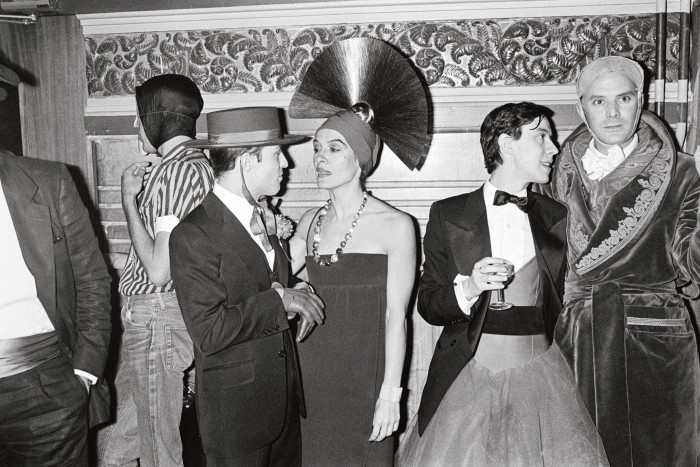

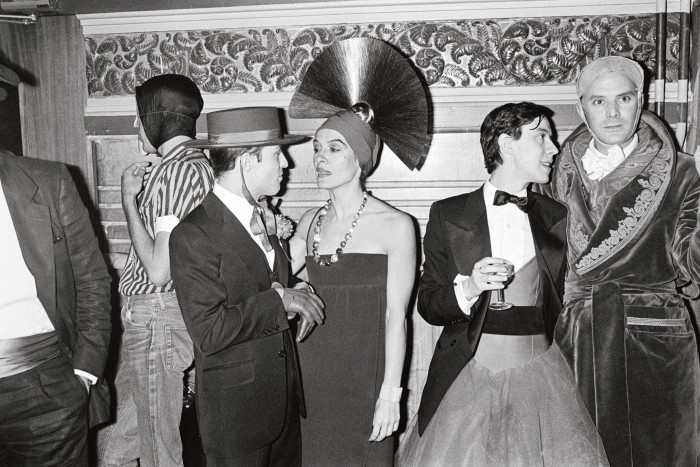

All the while, Blahnik was enjoying the social whirlwind that was London, a city he has always adored. His social network here seemed extraordinary. “People adopted me immediately – maybe because I was like a peacock; maybe because I was different to the other children. It was like a paradise. All those people on the King’s Road – that was my world and I loved it. I’m not nostalgic, but I think sometimes about those years and how wonderful it was. Nothing was prepared – it was totally spontaneous.”

Blahnik lived in Notting Hill, in an apartment in Colville Terrace. On another floor lived Peter Schlesinger, Hockney’s former lover and muse, and the artist Eric Boman, who would become Schlesinger’s companion for more than 50 years. The trio would go almost daily to the National Theatre – and to parties. “Oh my god,” he cries. “In my first decade in London, every night there was a party going on, with Bianca [Jagger]. In a night there would be four, five, six parties.” On a regular evening, Blahnik would leave his shop and cycle first to Jagger’s house on Cheyne Row. “I’d put on a jacket, a huge hat, and get out… then come back, a quick shower, and then, boom, back! Out again. I slept only three or four hours a night.”

He can’t drink wine or champagne – he’s allergic. “And I’ve never liked drugs at all. I’m very boring: I just liked drinking vodka.” He remembers another bash, Mick Jagger’s birthday, where “there was a wonderful woman from The Mamas & the Papas – and she died after the party”. He means Cass Elliot, aka Mama Cass, who died in the summer of 1974. “My God, I danced non-stop with her.”

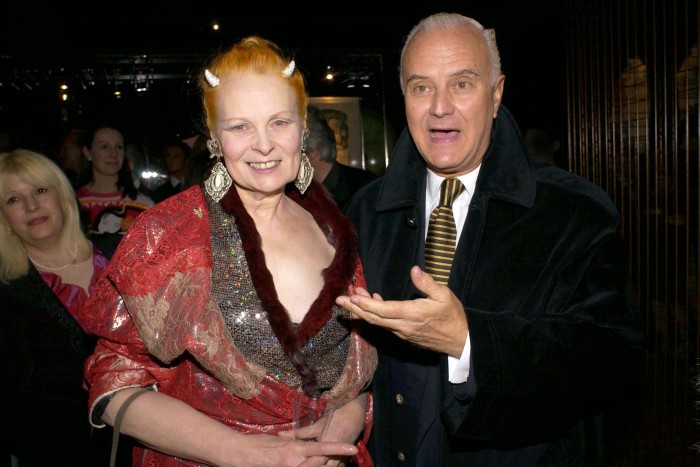

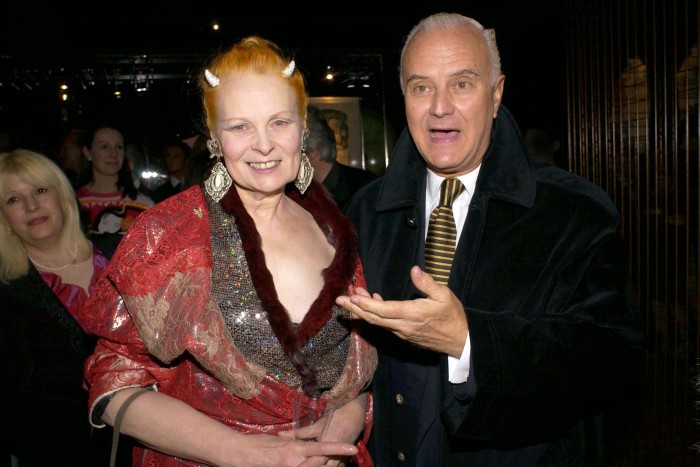

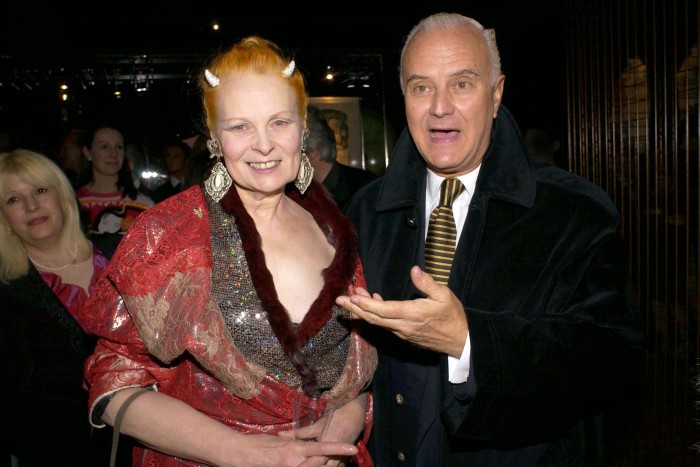

His favourite celebration ever, though, was the one that Karl Lagerfeld held for Paloma Picasso’s wedding in 1978 in his Paris apartment. “I’d never forget this party, ever, simply because it was the most beautiful. There was no electric light – everything was candles. Anna Piaggi [his close friend, and a famously eccentric fashion plate] was wearing a huge hat with feathers, and she started to catch fire. People just threw their napkins and water on her, and she didn’t even notice…”

He has also been photographed by many of the greats: Penn, David Bailey, Helmut Newton… Newton photographed Blahnik in a pinstriped suit and high heels. “Can you imagine? I did it for Helmut. He convinced me.” Blahnik has always been comfortable in his own heels, though. “I used to try the shoes on in the factory, size 42 or 43, which is my size.”

“I don’t mind,” he goes on. “I never thought there was much difference with men, women and things like that. It was natural for me, always.” He recalls seeing April Ashley, one of Britain’s first officially trans women, at the restaurant, and always saying hello. “Nothing is strange for me,” he concludes. “Nothing has really surprised me. I was born that way. I get used to things immediately.”

What is the secret of his longevity? Jones once asked him why he was so good. “Well,” he replied, “I am aware that my shoes are being worn with Jean Paul Gaultier, Valentino or many other designers, so I have to be so much better informed than any dress designer. Then I have to forget it all and design as I please.”

The stylist, writer and consultant Amanda Harlech says she has “worn Manolo’s exquisite shoes ever since a boyfriend sent me to Zapata” – Blahnik used to design for the label in his early days. “Pimento fine suede strappy sandals,” she recalls. “Shoes to dance in.” She sees parallels with Karl Lagerfeld, with whom she worked closely for decades at Fendi and Chanel. “Karl had this same mercurial gift of gathering the perceived world and reordering it into something new and strange and inspiring.” Blahnik, she says, “gives from his heart. I guess this is why he likes to be by himself, with his beloved dogs, sketching and dreaming.”

“I’m not very good at guessing what people want,” says the designer. “The shoes that really work are the ones where buyers say, ‘Ooh, nobody’s gonna buy that, it’s too expensive, it’s too difficult to wear…’ And it’s the biggest shoe that sells!” He cites a recent example from his new men’s collection, the Mario (£1,045), a pump covered in patchwork jacquard, or a classic like the Carlton (£975), garnished with a big “Beau Brummell-ish” crystal buckle. “And then I do a very modern shoe, and it doesn’t sell at all.” Blahnik famously loathes sneakers, though he likes an old-school tennis shoe and does those too (the Semanado is £525). “I stick with what I like, and that’s it.”

In a world gripped by vanilla fashion – be it athleisure, gorpcore or quiet luxury – Blahnik reminds us of that clientele still “famished for beauty”, to paraphrase his old friend André Leon Talley. And the trends are coming back around to him as well. Sportswear is giving way to a greater emphasis on tailoring. “I’m so glad,” says Blahnik. “Because that’s the way you can buy things and have them forever. And then you combine them with new things – this is called style, you know?”

It’s better, he says, to buy good-quality things – although even these will fade eventually: he is currently mourning a green cashmere suit, sent to him personally by Ralph Lauren. “The trousers are now French lace!”

It seems inappropriate even to mention retirement, though he clearly feels the business is in safe hands. Kristina, he says, has worked in almost every department: “As a child, she spent time at our Old Church Street shop, so she understands the company from its foundations.” Kristina herself recalls brushing all the suede shoes in the store after doing her homework. She took over from her mother, Blahnik’s sister Evangelina, who became managing director in 1981. With Evangelina, the brand went beyond its New York and London poles and moved into the Asian and Middle Eastern markets, most notably; Kristina has “widened it into the digital realm”. Next up will be a proper expansion in China, after the Blahniks last year won a 22-year legal battle with a businessman to wrest back total control over the Manolo Blahnik trademark. In 2024, they plan to open their own stores in China, never having sold any product in that market before. “It will be a huge market for us,” says Kristina. “It’s very exciting.”

Asked how he felt about entering his 80s, Blahnik says he “never thought about it much”. He does realise, though, how lucky he is to have got this far. “Sometimes I say to myself, ‘Good Lord – maybe I should have lived more?’ But I have, in fact, I realise. I have no regrets or things like that.” He promises that “I’m not scared of dying at all. No. I’m scared of having pain.”

In fact, he had yet another health scare two years ago when he was told he was in danger of becoming diabetic, and had to cut out sugar – “even carrots”. This was a huge blow to a man whose favourite cocktail was a Banana Daiquiri, and whose sole ambition on returning to London is to get to Wiltons, in Mayfair, in order to eat its bread-and-butter pudding. However, there is hope. To signal the end of our interview, a small, brisk man enters the room and tells Blahnik that “we need to get you changed, I’m afraid”. Blahnik sighs and protests, but there is an inducement. The assistant, or consigliere, brandishes a box.

“What are they?,” asks Blahnik. “Truffles? You’re so cruel…” Cue a farce around whether he can have one – or how many. Pretty soon he is unwrapping the sweet and scoffing it, letting out moans of pleasure. “Mmm, mmmm, mmmmm,” he cries. “For me, it’s totally orgasmic. Not that I remember what that is, but…” His entourage falls about, tittering. It’s clearly not his last bite.

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.