Of all the ancient Egyptians who wore kohl, Queen Nefertiti reigns supreme. But the elusive royal was far more than just a pretty face, and it would be unjust to limit her memory to her physique.

Not much is known about Nefertiti’s life, and what is known is often contested. Nevertheless, scattered clues outline an intriguing portrait. Nefertiti served as queen alongside her husband, King Akhenaten, during his seventeen-year tenure in the fourteenth century BCE; she was one of many wives, and the pair likely wed when they were teenagers. It’s unclear why Akhenaten married Nefertiti, though her beauty might have played a role. The identity of Nefertiti’s parents is unknown, and there are unanswered questions about her racial and ethnic background. Some believe Nefertiti was born outside of ancient Egyptian royalty, and that she may have been a princess from Syria’s Mitanni Kingdom. Others speculate she was the daughter of Ay, an adviser who later became pharaoh.

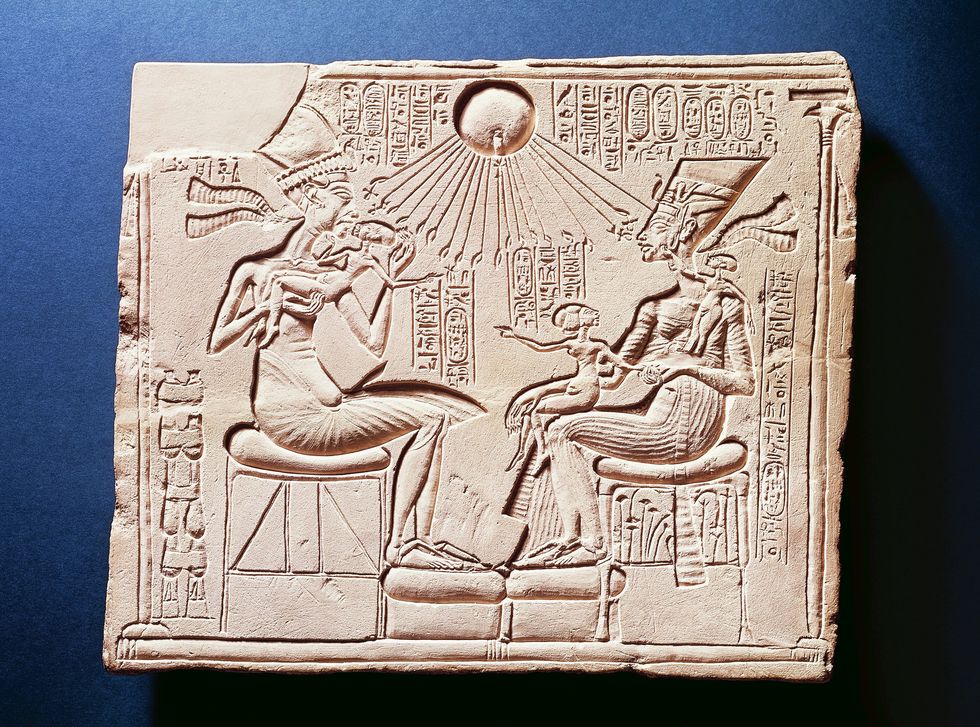

In various representations of Nefertiti, the queen appears more prominently than her husband—signaling she had both beauty and power. The pharaoh seemed quite keen on his wife, with imagery of the two showing them kissing and frolicking, a departure from the era’s typical portraiture. Nefertiti also had certain religious duties and participated in worshipping rituals with her husband. Far from a passive figurehead, she is also depicted in limestone blocks attacking her enemies by pulling their hair or wielding a sword.

Art, architecture, and religion were overhauled during Nefertiti’s lifetime. With the queen by his side, the pharaoh tore up every rulebook, abandoned polytheism, and instructed his people to turn to monotheism and devote themselves to Aten, a sun god, in a religious system known as Atenism. A new capital city, Tell el-Amarna, was built and dedicated to Aten. Cliffs surrounded the area, cutting it off from the rest of the empire. Temples were constructed without roofs so sunlight could pour into them.

Through it all, Nefertiti remained a source of strength for both Akhenaten and his subjects: “She would live through an unprecedented storm of events that called upon her to become a stead-fast and calm leader who could heal the deep wounds inflicted on her people during the strangest, least traditional time Egypt had ever known,” writes Egyptologist Kara Cooney in When Women Ruled the World. “Nefertiti would receive no credit for this political leadership, even though it was she who started the restoration of a country turned upside down, setting Egypt to rights at its darkest hour.”

Historical documentation about the queen ends twelve to fourteen years into Akhenaten’s rule. After that, her name was effectively dropped from the record. Some have speculated she ditched Atenism and fell out of Akhenaten’s favor, died from a plague or other illness, or took her own life after losing three of her six daughters (among her living daughters was Ankhsenamun, who would become the wife of Tutankhamun). Others say she was deserted as she hadn’t borne Akhenaten a son.

Either way, Nefertiti apparently vanished. However, following her mysterious disappearance, Akhenaten took on a co-regent who some argue may have been Nefertiti herself. Historian Joyce Tyldesley, author of Nefertiti’s Face, argues Nefertiti was more likely a deputy, while Cooney posits Nefertiti probably ruled as co-king, “even installing the next king,” and that “more than any other Egyptian queen, it is Nefertiti who represents the epitome of true, successful female power.”

The changes Nefertiti helped spur would ultimately also vanish into thin air. Akhenaten’s imposition of monotheism came to an end when he died; those who disapproved of his upending of tradition reinstated polytheism, and Tell el-Amarna was abandoned.

The remaining clues to Nefertiti’s life and the period during which the power couple altered Egyptian faith and art may lie in her tomb, which, at the time of writing, has not yet been found. Egyptologists everywhere continue to deliberate its whereabouts—one of these Egyptologists, Zahi Hawass, tells me he believes the grave is in the West Valley of the Kings and he’s hopeful excavators will soon find it. More specifically, British archaeologist Nicholas Reeves has surmised that Nefertiti is buried in a hidden chamber within Tutankhamun’s tomb.

Much is still unknown. We can, however, be sure the queen wore kohl purposefully and abundantly. Multiple images of her carved into stone show her large eyes framed with black lines.

And then there’s her bust.

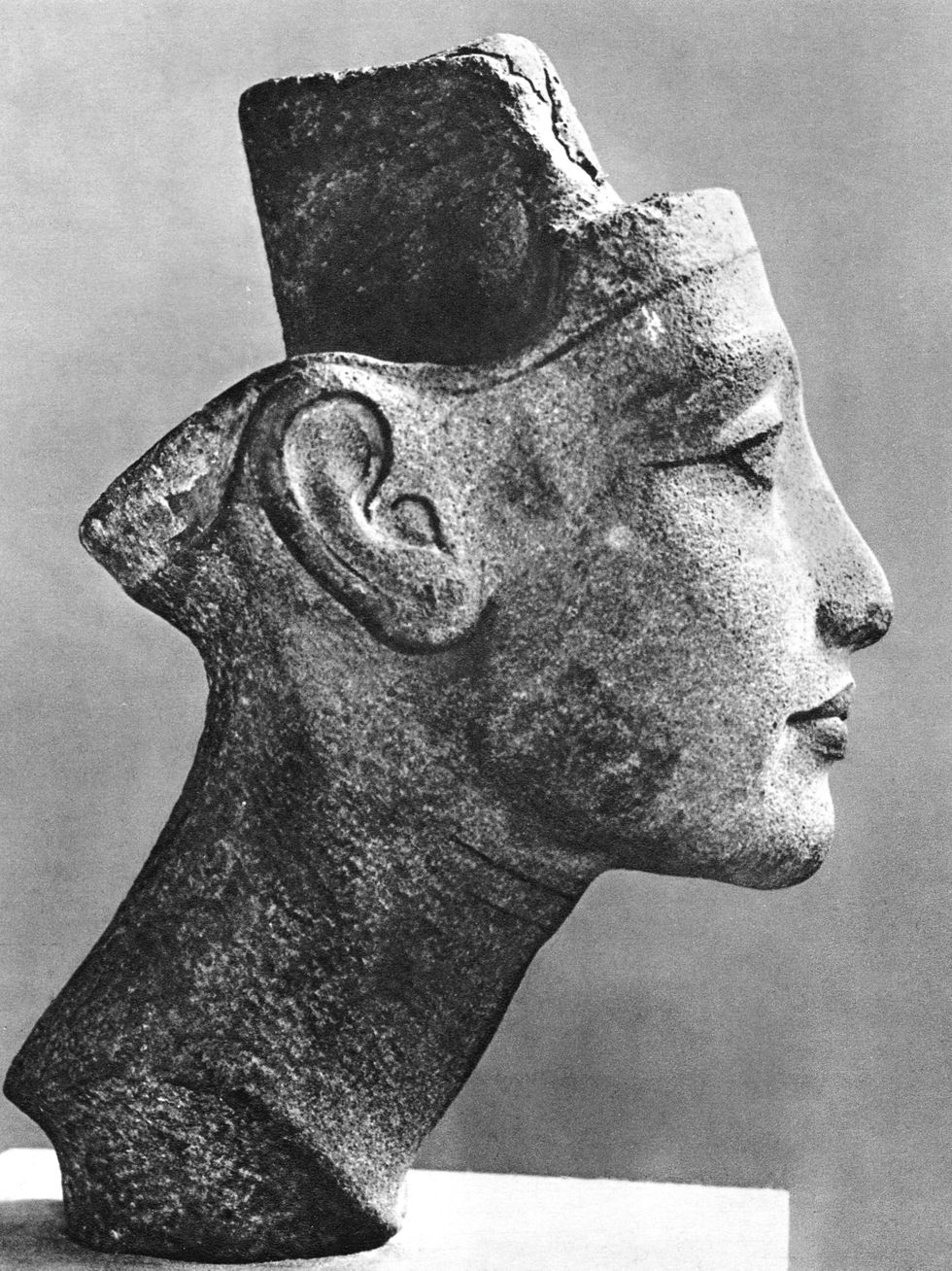

When Mohammed el-Senussi was pictured with Nefertiti’s bust after it was discovered along the left bank of the upper Nile Valley on a sunny afternoon in December 1912, he appeared to be cradling it like it was a newborn baby. Understandably so—the multicolored limestone sculpture in the foreman’s hands hadn’t seen the light of day in over three thousand years. The stucco-coated artwork weighed forty-four pounds and was eighteen and a half inches tall. It emerged whole and relatively unblemished from the sands of the Egyptian desert, save a missing left eye and minor damage to its ears and crown.

“Suddenly we had in our hands the most alive Egyptian artwork,” wrote Ludwig Borchardt, the mustachioed German archaeologist who led the expedition and later “moved” the bust out of Egypt and into Germany. Words, he declared in his field notes, failed to convey the impression Nefertiti’s representation had left on him. And they couldn’t possibly capture the sculpture’s delicacy. “You cannot describe it,” he said. “You must see it.”

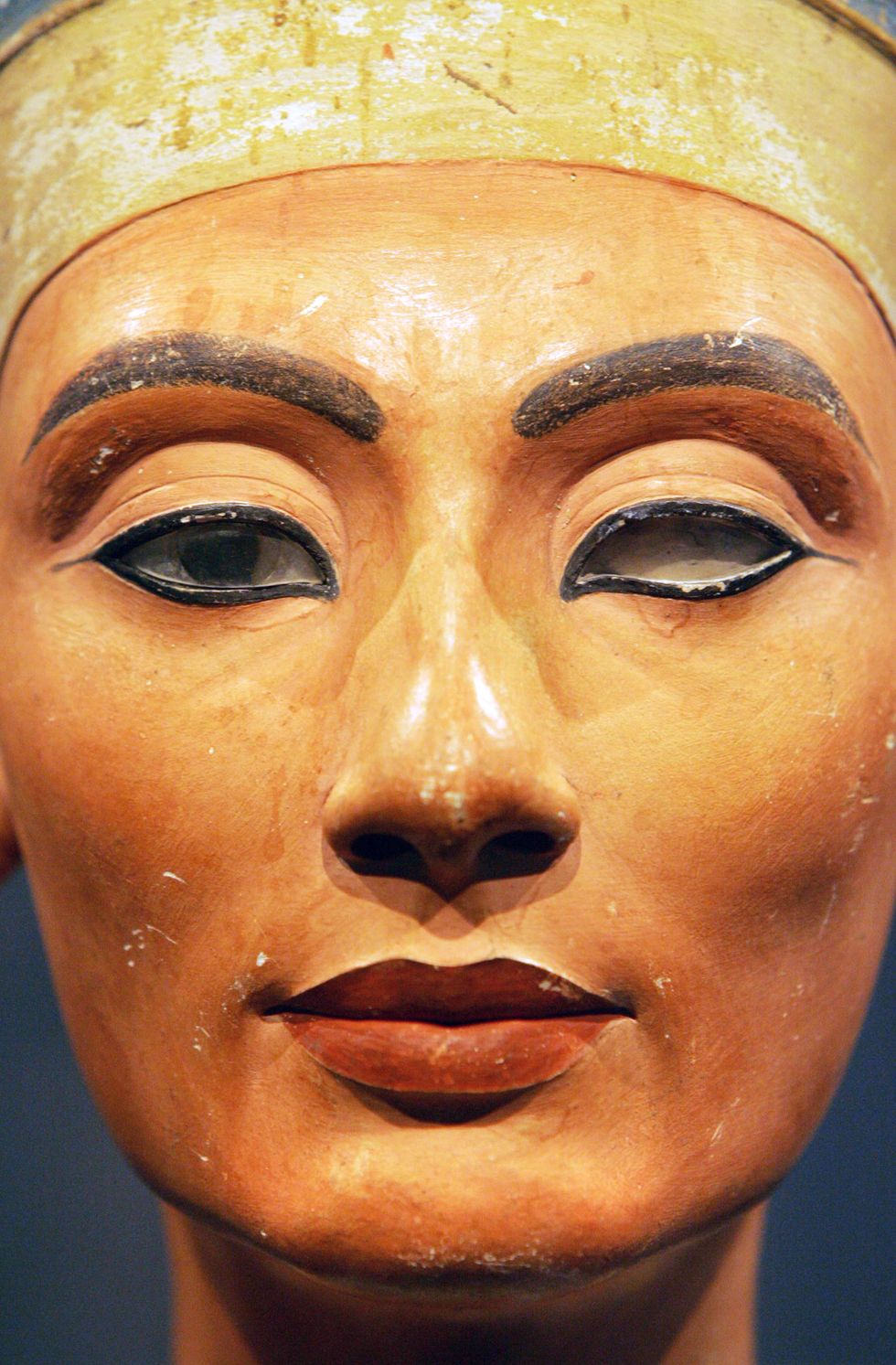

In this rendering, Nefertiti’s face is stunningly symmetrical, with a visage about one and a half times longer than its width. The breadth of her lined, almond-shaped eyes equals the distance between them. And her straight-edged nose is roughly the same length as her forehead. Nefertiti’s cheekbones are so pronounced as to appear naturally contoured; they would be the envy of Kim Kardashian herself.

Together, these facial proportions mean Nefertiti’s face would score highly if measured against the so-called golden ratio, a proportion thought to be aesthetically optimal. During the European Renaissance, artists used the equation to model sculptures and paintings. And app filters on TikTok today turn to it as a formula to determine, quite unforgivingly, what is hot and what is not. Celebrities with this particular beauty badge of honor include supermodel Bella Hadid and, unsurprisingly, Beyoncé.

These striking features sit atop a famously slender neck that is commonly described as “swanlike.” The queen’s slightly pointed chin accentuates her neck’s length while softening her robust, square jawline. (A cosmetic procedure known as the “Nefertiti lift” promises the appearance of a longer neck and a more defined jawline. The costly enhancement is made possible by a dozen small Botox injections strategically placed in the face, jaw, and neck area. In 2009, a British woman revealed to the Daily Mail that she’d spent a quarter of a million dollars on fifty-one plastic surgeries to mimic Nefertiti’s looks. In images of her on the paper’s website, she’s wearing eyeliner as the queen did.)

Nefertiti’s skin tone, per her bust, is terracotta with undertones of warm sandstone, suggesting she was quite literally a woman of color. In his excavation diary, Borchardt described the shade as “light red.” According to Tyldesley, the color of Nefertiti’s skin—as it is shown on her bust—tells us little about her race. Ancient Egyptian portraiture often showed men with red-brown skin and women with yellow-white skin to distinguish the genders. By that logic, the pigment used on Nefertiti’s bust was closer to what was typically used to depict men.

The dyes Nefertiti’s sculptor used to color her chiseled face point to what may have been in the queen’s makeup palette: her Cupid’s bow lips were full and painted marsala brown, and her eyebrows were arched, shaped to perfection, and filled with smoky black dye, possibly kohl. The color contrast is stark, yet the queen’s overall appearance is seamless. Nefertiti’s makeup is, in fact, on trend: there are hundreds of tutorials on YouTube, TikTok, and Instagram mimicking the queen’s face with a great degree of precision.

All features considered, the allure of the queen’s eyes—framed with thick black lines—is unparalleled. The lines are perfectly symmetrical, meeting at the edges of the eyes to form her trademark flicks. From a strictly aesthetic perspective, the tracing defines and widens the windows into Nefertiti’s soul, lending them a fresh-looking yet sultry appearance.

From EYELINER by Zahra Hankir, published by Penguin Books, an imprint of Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House, LLC. Copyright © 2023 by Zahra Hankir.

Journalist

Zahra Hankir, a Lebanese British journalist and the editor of Our Women on the Ground, writes about the intersection of politics, culture, and society, particularly in the broader Middle East. Her work has appeared in publications including Condé Nast Traveler, The Observer Magazine, The Times Literary Supplement, BBC News, Al Jazeera English, Bloomberg Businessweek, the Los Angeles Times, and The Rumpus. She was awarded a Jack R. Howard Fellowship in International Journalism to attend the Columbia Journalism School and holds degrees in politics and Middle Eastern studies.

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.