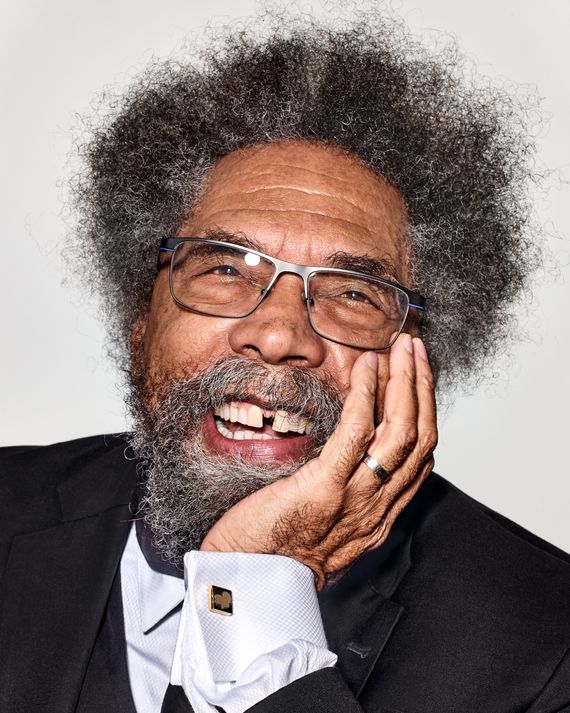

Photo: Richard Burbridge

It’s a scorching Friday in late August at Marshall’s Music and Book Store in Jackson, Mississippi, and Cornel West is causing such a logjam that no one can get in or out. “Coach!” he cries as he gives Andrew Campbell, the man coordinating the visit, a full-bodied hug. “My brother, my brother!” — that’s for Kareem Muhammad, an activist who mirrors West’s enthusiasm with a toothy smile. “Brother Zak, you all right?” he asks me, holding the door open so that I can squeeze inside. “Lord, lord, lord, lord, lord, lord, what a blessing to see you all,” he exclaims, posing for photos with several clamoring women and bowing as Maati Jone Primm, the shop’s regal proprietor, emerges from a back room.

Was this part of his campaign launch? I was confused. West had told me his presidential run would kick off on August 28, then sent me an email on August 24 saying, “The events begin tomorrow my brother!” On the next morning’s hastily arranged flight to Jackson, I checked YouTube. “We’re gonna launch our campaign August the 25th in Mississippi,” West told the Black in Appalachia podcast, which seemed to settle the matter. But I’d also gotten a text from West’s wife, Annahita Mahdavi West, insisting, “There is no launch event.” When I finally meet him in person, West tells me he might not hold an official launch at all, and I’m satisfied until I hear State Representative De’Keither Stamps speak at an event in the town of Lexington. “He could’ve launched his presidential campaign somewhere else in the world,” Stamps says before West takes the stage, “but he decided to come to Holmes County.”

Since West announced his third-party bid for the White House in June, he has been in the Democrats’ crosshairs, and this shambolic rollout is doing nothing to dispel the notion that his campaign is somewhere between a vanity project, an election spoiler, and an excuse to get on television. “This is not the time in order to experiment,” scolded Democratic National Committee chair Jaime Harrison in July. After announcing as a People’s Party candidate, West switched to Green and hired Jill Stein to be his interim campaign director. Stein’s perceived role in Hillary Clinton’s loss to Donald Trump in 2016 is still a sore spot for the liberal left, though aggravating Democratic trauma might have been part of the point: West’s announcement video featured interviews with Bill Maher, who has compared the “woke revolution” to Mao Zedong’s Cultural Revolution, and the podcaster Joe Rogan, who has praised Ron DeSantis. Stein was replaced in September by the peripatetic political adviser Peter Daou, whose tenure overlapped with West’s decision to abandon the Green Party and become an independent. “He believes the best way to challenge the entrenched system is by focusing 100 percent on the people, not on the intricacies of internal party dynamics,” read the campaign’s announcement — three weeks before Daou, too, resigned in October for mental-health reasons. (Daou’s parting message hinted at chaos behind the scenes. “I saved Cornel West’s campaign,” he wrote on X, “from financial insolvency and complete internal disarray.”)

Still, it’s a little surprising, given his knack for provocation, that West has never run for public office before. A lifelong Baptist, he has spent most of his 70 years as one of America’s premier public intellectuals. His face adorns many of his 18 books, including the best seller Race Matters, making him the rare college professor you’d recognize in silhouette. His signature Afro and black-rimmed glasses have been familiar sights in both the halls of the Ivy League and the ranks of teeming protesters. His sermonic lectures and frequent media appearances, in which he riffs on race and politics from a Christian “non-Marxist socialist” perspective, have inspired fans from college freshmen to Hollywood directors. When the Wachowskis cast West in the Matrix trilogy, it was because his intellectual preoccupations mirrored their own — the revolutionary potential of multiracial egalitarianism, skepticism of authority, the sublime power of creative expression.

His fame means he gets mobbed everywhere he goes. West lands in places like Jackson with no clear idea of his itinerary, trusting that his hosts will shepherd him from one venue to the next. Today, there’s just one problem: no car. “I have a rental,” I offer, and just like that I’m his chauffeur for the evening. West slides into the back seat of my Nissan Altima — his wife and his friend Noah Stout, a documentary filmmaker, are there as well — and starts blissfully tapping his kneecaps along to the music (“Crisis,” by the jazz trumpeter Freddie Hubbard).

Our stop after the bookstore is the Mississippi Civil Rights Museum, where the Emmett Till Legacy Foundation is marking the anniversary of Till’s 1955 lynching by having West speak. “Mississippi is ground zero for the Black freedom struggle in America!” he bellows. His remarks are, as usual, delivered extemporaneously. A screening of the 2022 movie Till, which West watches raptly, follows, then a panel discussion with some of the filmmakers. As I rise to meet West at the front of the auditorium, I get caught in the rush of attendees hurtling toward his shock of salt-and-pepper hair, phones ready.

It soon becomes clear that we’ll be here a while longer. West may be hard to pin down, but once you do, he’s really there. The hints most people give when they want out, drifting eye contact and furtive glances toward the door, don’t exist in his physical vocabulary. Even when he wants to go home and begins weaving toward the back exits, people follow him into the hallways: “Just one more photo, Dr. West!” He always obliges. When we finally escape, I sense no relief, just murmurs of appreciation for all the nice people he’s met.

West has been doing a version of this for more than 40 years. It’s what has sustained him — life on the road, spreading his gospel, the adoration of strangers. He fancies himself “a bluesman in the life of the mind,” as he wrote in his 2009 memoir, Brother West, traveling from town to town like the bards of the Mississippi Delta. He loves it so much he hasn’t quit the lecture circuit to campaign full time, though he is on sabbatical from his teaching job at Union Theological Seminary. Owing in part to the shortfalls that plague most third parties — “I’ve got to raise more than a million dollars just for ballot access,” West tells me — the Green Party did not underwrite this August trip. He paid out of pocket.

He has hardly slowed down since leaving Mississippi. In the months since, he has granted interviews to an astonishing range of audio, television, and web programs, from ex–Bernie Sanders press secretary Briahna Joy Gray’s Bad Faith podcast to Hannity on Fox News to a local TV station in Melrose, Massachusetts. He marched alongside religious leaders and youth activists for New York’s Climate Week in September and walked the picket lines with striking autoworkers in Wayne, Michigan. Most recently, he joined the October student walkout at UCLA in solidarity with embattled residents of the Gaza Strip, who are currently under bombardment by the Israeli military, and courted further controversy by accepting and then refunding a $3,300 campaign donation from right-wing megadonor Harlan Crow.

It helps that West eats one meal a day, claims to sleep three hours a night, wears the same funereal three-piece suit all the time, and says he hasn’t had a haircut since the mid-1990s. But it’s an unsustainable pace, as even he acknowledges, especially for an election that he has almost no chance of winning and that he might end up throwing to Donald Trump. At risk, too, is his legacy as a champion of the forgotten and the oppressed, though the way he sees it, the greater danger is that no one would take on that role at all. Who else is going to do it on the biggest stage in politics if not Cornel West?

September 19, 2023: Speaking at a march for the Global Fight to End Fossil Fuels in New York.

Photo: Courtesy of Dr. Cornel West

For the past decade, the prevailing narrative about West was that he’d lost his way — dismissed by the Democratic rank-and-file as a petty narcissist and by leading academics as a hack who hasn’t produced meaningful work in years.

After a celebrated stretch in academia that took him from Harvard and Princeton to Union and Yale Divinity School, West saw his fame explode with Race Matters, a diagnostic look at the ills of American racism published one year after the L.A. riots. In 1993, race relations were marked by widespread ignorance about life in poor Black neighborhoods. There was a sense that, after being granted equality by the civil-rights movement, Black people weren’t holding up their end of the bargain — liberal policies had robbed them of their initiative, argued leading Black conservatives like Glenn Loury. The assault on Rodney King shocked many people because their understanding of Black life was gleaned from a mix of The Cosby Show and the evening news, the former a fantasy of respectability politics and the latter a steady diet of cops-and-robbers parables.

Hip-hop was the rare form of media to cast light on ghetto conditions, but many Black leaders, like C. Delores Tucker and Eleanor Holmes Norton, saw it as an affront. The Reverend Calvin O. Butts drew headlines in 1993 for staging a protest where he planned to literally steamroll a pile of rap tapes and CDs. Other Black pastors railed against Black immoralism, while the “tough on crime” and anti-welfare crusades of the Bush and Clinton administrations wreaked havoc on Black neighborhoods with broad public support. For many Americans outside the ghetto, racism had lost its ability to explain Black inequality — Martin Luther King Jr. had been given his own holiday, after all.

Race Matters arrived as a correction, offering what Michael Eric Dyson, West’s mentee turned friend turned adversary, called “a golden pun” for how racism remained stubbornly salient. It stitched the legacy of slavery and Jim Crow to the plight of the contemporary ghetto, explaining with both the force of the pulpit and the lucidity of a scholar the ways in which racism continued to haunt and oppress. Its overriding argument was that, in the absence of a robust and honest public conversation about race, structural flaws in American society had been reduced to products of Black pathology, leaving Black people alone responsible for fixing them. It’s a slim volume, at just over 150 pages, that presaged modern essay collections like The 1619 Project and The Fire This Time and filled a discursive gap felt everywhere from Bill Clinton’s White House to my own childhood home, where it stood on my parents’ bookshelf. The book has since sold more than half a million copies and earned its author, then just 39, a Time profile and a Newsweek profile in the same week. “I was asked to speak everywhere,” wrote West of his sudden fame.

Ironically, it was the rise of a similar figure — an electric speechifier and thinker who combined the pedigree of academia with a cogent vision of the color line — who triggered the erosion of West’s reputation. In 2007, after a long phone call with then-Senator Barack Obama, West decided to endorse his presidential bid despite not knowing him. West was a longtime skeptic of America’s Black leadership class and its alliance to the Democratic Party, which he saw as militaristic and beholden to corporate interests. But Obama, who had distinguished himself by taking an early stand against the Iraq War, convinced him to hit the trail as a surrogate, where he did dozens of events and played what his close friend, the broadcaster Tavis Smiley, describes as a pivotal role in introducing Obama to Black voters. “We knew the Clintons; we didn’t know him,” Smiley says.

It should have been a powerful alliance. But in January 2009, West found himself in Washington, D.C., without tickets to the inauguration. (“Not so much for me; for my mother,” he explains.) He was offended and not ashamed to say so, which made his later political critique hard to separate from his personal animus. And after Obama had won West’s endorsement by saying he intended to carry on King’s legacy in office — which West took to mean a rejection of militarism and oligarchy — his escalating drone wars and kid-glove treatment of Wall Street came as further betrayals. “It’s not personal at all,” claims Smiley of the dispute, “except in this one way: If you know Cornel West, what he cannot stand is ingratitude.”

“I’m going to get ghetto,” says West, who is less restrained. “He lucky I didn’t kick his behind.” This acrimony lasted for the duration of Obama’s presidency and was the impetus for West and Smiley’s “Poverty Tour,” in which they traveled the country hosting forums on the plight of the poor. West’s broadsides were rarely tactful — he called Obama “a Rockefeller Republican in blackface” — and their searing tone took his friends and allies aback. “Professor West offers thin criticism of President Obama and stunning insight into the delicate ego of the self-appointed black leadership class that has been largely supplanted in recent years,” wrote Melissa Harris-Perry, then a Princeton colleague, for The Nation. A lot of the anti-West backlash stemmed from strategic considerations that West had never shown much interest in. The sense was that Obama, as the face of Black achievement, merited some slack, and anyway he was far preferable to the GOP; the 2012 election was approaching, and many felt that a Black critic of West’s pedigree could knock Obama off his political tightrope.

By the time Dyson published a critique in The New Republic in 2015 dismissing West as “a curmudgeonly and bitter critic” who had become irrelevant, West’s reputation as a mudslinging egomaniac was set. The sour aftertaste of the rift lingers. West is still not friends with Dyson or Harris-Perry, and his harsh assessment of Obama still rankles loyal Democratic voters. When I told my mother I was writing about him, her first question was “Are you going to ask about all that time he spent bad-mouthing Obama?” West has only compounded his notoriety with further imprudence that suggests, to some, that he can’t brook any Black intellectual taking his limelight. In a 2017 Guardian op-ed, West excoriated the writer Ta-Nehisi Coates as a “neoliberal” who refused to analyze class or criticize U.S. militarism. Coates responded with links to essays in which he’d done just that.

It can still be hard to discern where West’s intellectual convictions end and his personal grudges begin, and the latter often threaten to overshadow the former. But it is also impossible to disentangle his late-career reputation from broader Black ambivalence about America’s first Black president, who was simultaneously a symbol of triumph that had to be protected and an object of disenchantment for becoming the very sort of out-of-touch Democrat whom West built his career calling out. The social-justice movements that erupted from a series of police killings in Obama’s second term, the signs of young Black voters moving away from the Democratic Party, and Obama’s own decision to turn his post-presidential career less toward civil rights than celebrity-driven content creation and Wall Street speaking gigs — all have contributed to the impression that there is potent Black dissatisfaction with Obama and his party, even if other people don’t express themselves as baldly as West does.

January 21, 2008: Applauding Barack Obama at a Martin Luther King Jr. Day rally in Columbia, South Carolina.

Photo: Elise Amendola/AP

The notion that West is running for president as revenge for Obama slighting him in 2009 is so ingrained that he addresses it without being asked. “I was listening to my dear brother Billy Michael Honor,” he tells me at a quaint wooden conference table off the lobby of the Fairview Inn in Jackson. Honor used to do faith and civic organizing for Stacey Abrams’s New Georgia Project. West paraphrased Honor’s comments on a recent podcast episode: “‘Five out of ten Black folk say West is running for president because he’s mad Obama didn’t give his mama a ticket.’” West cackles incredulously through his Methuselah whiskers. “Boy, I love Black folk!”

The reality is that West has never had patience for Black leaders who don’t throw in their lot with the Black poor, a neglect that he has spent decades using traditional channels to address. After spending two elections as a surrogate for Bernie Sanders, his brief alliance with the Democratic Party’s insurgent left flank — embodied by officials like Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez — has given way to disillusionment. “I think they treated Bernie very unjustly,” he tells me, echoing a conviction among the senator’s supporters that the Establishment undermined him at every turn. A third-party bid struck West as the only defensible option, given what he saw as the Democratic Party’s fealty to big business and imperial expansion.

In recent years, West has focused his ire on the Biden administration. Citing Robert Kuttner and Harold Meyerson of The American Prospect, he says, “It’s amazing to hear people who I have had great respect for say things like, ‘This is as good as the economy gets. Thank you, Mr. Biden.’ And I say, ‘Good God, I’m on 110th Street in Harlem, man. I walk out of my apartment, you got unhoused brothers and sisters and levels of grotesque wealth inequality.’” I suggest despite it all that Biden may be the most progressive U.S. president of my lifetime — not the highest bar, certainly, but surely his efforts to reduce poverty and withdraw from America’s longest war count for something.

He hasn’t been progressive “under non-pandemic conditions,” West replies. “I give Biden credit for that moment on child poverty.” (2021’s American Rescue Plan slashed child poverty in part by issuing monthly payments to families — progress that evaporated once the payments weren’t renewed.) West doesn’t “think Biden has ever been intentionally and conscientiously anti-poverty in terms of a substantive move.” Any suggestion otherwise minimizes the scale of the problem. “Don’t lie about the cat,” West implores. “I see the same thing when I heard my dear sister AOC — God bless her, I love my sister. She’s brilliant. But when she says that Biden has actually been good, that’s going to hide”his true record. As for foreign policy, Biden has been “consistently militaristic,” West tells me in August. “Ukraine is just the beginning. We’re probably on the way to Taiwan, and Egypt and Israel continue to be the major recipients of military aid, and that increases each cycle.”

It wouldn’t take long for his analysis to be vindicated. In October, after Hamas militants breached the border from Gaza, killing 1,400 people and kidnapping over 200 more, Israel’s government responded by launching weeks of air strikes, followed by a ground-troop invasion, which together have killed more than 9,000 people, mostly women and children. Biden offered nearly unequivocal support for the onslaught, refusing to publicly press for a cease-fire and even casting doubt on the Gaza Health Ministry’s account of the death toll. Protests in solidarity with the residents of Gaza erupted across the U.S., castigating Biden for abetting it. The president’s polling numbers took a hit, plummeting 11 points to a record low of 75 percent among Democrats, according to Gallup. West took the opposite tack, first appearing on Sean Hannity’s show to explain how Israel’s oppression of Palestinians had fomented a violent rebellion, then joining UCLA students who were staging a walkout. “We want equal dignity, equal rights, and equal status for Palestinians and Israelis,” he announced on X before heading to Los Angeles.

October 28, 2023: Marching in support of Palestinians in Downtown Los Angeles.

Photo: Photo by DAVID SWANSON / AFP/AFP via Getty Images

West’s stance on Israel articulates a growing disaffection with Establishment Democrats felt across the left after 2016. Still, I ask about the argument that his campaign could harm the downtrodden even more by siphoning off crucial progressive votes. “It’s motivated by a real fear of Trump and neofascism, which is totally understandable,” West says. “But the same question has been asked every four years for decades” — including when West previously rejected such reasoning in 2012 — “and sooner or later you got to come up with an alternative. They think every vote for West would’ve been Biden — not at all. Some folk are never going to vote for Democrats, Republicans, or Biden, or Trump, or anybody else. They just give up.”

Most Democrats wish he’d stop. Ro Khanna, who was Sanders’s campaign co-chair in 2020, is an outlier who has welcomed West’s candidacy as a way to “bring more people into the process.” I ask West if he’s spoken to Sanders. “No, no,” he says quietly. “Bernie and I haven’t talked at all since my campaign took off.” He nods, as if lost in thought. “I have a deep love for Brother Bernie, but we just disagree on this thing. My hunch is his argument would be that it needs to be all persons on deck to hold off Trump.” (Two days later on CNN, Sanders makes that exact argument while referring to his “dear friend Cornel West.”)

West’s vision for his presidency is practically utopian. The platform on his campaign website includes items like climate reparations and ending patriarchy. It is so starkly at odds with the legacy of the Oval Office that Smiley has trouble reconciling that track record with West’s desire to be president. “It has been difficult for me to square the Cornel West that I know with an interest in being the leader of the American empire,” Smiley says. “If I had it my way,” West tells me, “I would be head of the empire to thoroughly dismantle it.” West runs down his “to do” list: “You begin with trying to abolish poverty and homelessness, and that requires massive disinvestment in military units around the world,” he says. I ask how he plans to win. “Biden’s cognitive decline is becoming more and more undeniable, God bless him,” West says. “He may not even end up being a candidate. Trump may end up in jail, and lo and behold, that 33 percent that will support him no matter what begins to erode to 25 and 20.”

And if that coalition doesn’t materialize? “It might be that America just doesn’t have the structural or civic capacity to undergo the kind of revolution I’m talking about,” he says.

Photo: Richard Burbridge

West hasn’t been a long-distance runner since high school, but he maintains the lean physique of someone constantly on the move. The sable goatee made iconic by his book covers has lengthened and grayed. (He says he never shaves — “I’m too busy.”) His suit is austere, though not without flourishes: Gold Africa-engraved cuff links glint from his wrists, and the left elbow of his jacket has ripped to reveal the lining.

Age has made him reflective. Annahita, a professor and psychologist, is his fifth wife, and West blames the four divorces largely on his yen for the road. In his writings, he has described struggling to balance his work with his responsibilities to his two children (it has been reported that he had an outstanding $49,500 child-support bill from 2003, which he tells me was resolved privately decades ago). West’s parents were married for 44 years until his father died, and in his memoir, he wonders with somber resignation at how he has failed at so many marriages. And even though his current union is full of intimate laughter and sweet smiles exchanged between him and his wife when he is at the podium, he knows he’s playing with fire. “None of my loved ones are crazy about it,” West tells me of his decision to run for president. Their objections, he says, hinge partly on the question of whether he’s doing more harm than good, which concerns not just the stakes of the 2024 election but his legacy. Earlier, I had mentioned my mother’s misgivings about him. “She is at her best — which is largely who she is — as part of the great tradition that I’m trying to keep alive,” he says, and he hopes she’ll look past the controversies and judge him by his record. “Lord, let my works speak for me.”

The hourlong drive from Jackson to Lexington is mostly tree-lined highway, but its emptiness evokes the desert — a landscape well suited to West’s growing preoccupation with death, which has given his campaign the feeling of a last hurrah. “As you get older, you think much more about death, dread, despair, disappointment, disillusionment, disenchantment,” West says. “I’ve always been interested in those themes, but of course you get to your own death and they take on a concrete force in your life.”

The town of Lexington could say plenty about the subject. He is here for two events meant to highlight a pattern of police abuses in the region as part of the Till commemoration weekend. “What would you do differently from any other presidential candidates?” asks Reginald Virgil, who works for the Mississippi branch of the National Association of Social Workers. West tells Virgil, who is young and Black and visibly tired of the Mississippi Delta being ignored by national politicians, “One of the fascinating things about America is that we really do have a tremendous amount of people with imagination, intelligence, and courage. But you would never know it from most of our political leaders. They’re just mediocre. Milquetoast. They tend to be tied to big money and big donors. Too often they’re in a straitjacket” — he turns to the audience and hunches his shoulders for emphasis — “like a jazzman or a jazzwoman in a military band. They’re not free enough. So at the spiritual level” — here he turns back to Virgil — “you have to have a free person in politics who will call into question the hypocrisy and mendacity of the political culture.”

The answer, in its freewheeling iconoclasm, is vintage West, made newly resonant at a time when being vivid and unfiltered are political virtues. I’d bet no other presidential candidate has ever used the term de-niggerization in a stump speech. (He’s talking about reversing the process by which “dignified African people” were recast as subhuman in the U.S.)

The location of the event isn’t very presidential. We’re in a long-neglected auditorium of what used to be Saints Academy, a historically Black private school founded in 1918 but without students or teachers since 2006; a cluster of mostly abandoned brick buildings is all that remains. Stamps describes Holmes County as having “the worst cell-phone service in the world,” a degree of infrastructural neglect that gets emphasized every few minutes by the low-battery beep of a hallway smoke detector. The security detail that’s been provided to West for the event includes two armed volunteers from the New Black Panther Party.

“I was told,” West goes on, voice rising, “that the kingdom of God is within you and everywhere you go, you ought to leave a little bit of Heaven behind. And you leave Heaven behind by not falling prey to the carrot of the powers that be, because you’re not impressed with what Pharaoh has!” The cheers from the crowd, which is about 50 people strong, punctuate his next moment of climactic humility. “I understand I’ve got the hatred and the selfishness and the greed inside of me,” West shouts, “but I’m working it out!”

West, Virgil, and the rest of our solemn convoy travel to a church in Brandon next, another hour’s drive away, where a panel of attorneys, activists, and members of Till’s family rattles off a list of atrocities afflicting local Black people — stories like that of Michael Jenkins and Eddie Parker, who were tortured for 90 minutes in January at a nearby home by six cops wielding stun guns and sex toys. “This is the only presidential candidate who’ll come here,” one panelist says of West’s presence, “who sees your pain,” and this strikes me as what makes him different — his willingness to show up, his capacity for not just empathy but solidarity. It’s hard to imagine this scene with a national Democrat, a fact that echoes in every “Amen” at West’s raspy proclamations.

On the way to the parking lot, I catch Virgil and ask him what he thought of West’s answer to his question back in Lexington. “I was satisfied,” he says after some hesitation, “but I wanted more.” He sighs and looks at the floor. “I get what I can take.” I ask him what he means by that, and he explains that it’s part of southern culture to absorb what an elder says, then parse its significance over time: “You gotta think about it. I’m appreciative because Dr. West could’ve diverted from the topic.” He raises his gaze to meet mine and shrugs. “I’m just satisfied he’s fucking here.”

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.