“I want to be a society vampire,” said Bernice, the protagonist in F. Scott Fitzgerald’s short story (1920). Encouraged by her devious, calculating cousin Margorie, Bernice believed “bobbed hair was the necessary prelude.” She, though, had no real “tonsorial intentions” to bob her hair but fell victim to a trap her jealous cousin had set for her.

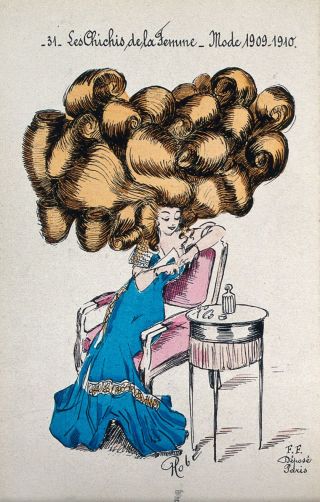

The “bob,” incidentally, was considered a “revolutionary” short hairstyle in the early 20th century. Before being widely accepted by the late 1920s, it was often associated with sexual promiscuity, as well as behaviors, such as smoking, drinking, and wearing make-up and short skirts, then controversial for women (Sherrow, 2006). The hairstyle presented an “androgynous silhouette” and “transgressed traditional gender” norms (Biddle-Perry, 2022)

Poor Bernice, fearing she had no choice, saw the barbershop sign, and the barber in his white coat, and “had all the sensations of Marie Antoinette bound for the guillotine…Would they blindfold her? No, but they would tie a white cloth round her neck lest any blood—nonsense—hair—should get on her clothes.”

Not only had Bernice’s decision created an “incendiary act of social indiscretion” in a small-town community (Biddle-Perry), but once her lovely long hair was cut, Bernice “flinched at the full extent of the damage that had been wrought…her hair was ugly as sin…and she was—well, frightfully mediocre…”

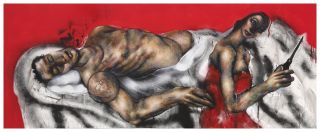

Clearly, Fitzgerald gives us an apt description of a so-called “bad hair day.” He, though, enables Bernice to get her revenge: While her cousin sleeps, Bernice deftly “amputates” Margorie’s own two lovely blond braids (Fitzgerald, 1920.)

Throughout the centuries, there have been many other stories reflecting the symbolic—i.e., metonymic—property of hair. In classical literature, for example, we have Homer’s Greek hero Achilles in a “black cloud of despair” and “heartbroken” upon hearing of the death of his beloved Patroclus, killed by the Trojan leader Hector.

“With both hands, he tore his hair” (Book 18). At the funeral pyre, Achilles’ comrades “blanketed the corpse with their own hair, which they cut off and threw on top…” Achilles then cuts his long “chestnut hair,” which he “dedicates” to Patroclus to take to the Underworld (Book 23). Significantly, he appreciates the enormity of his action—namely, because of vows his father had made to preserve Achilles’ hair, Achilles will never return home again (Wilson).

Further, the Roman poet Ovid tells of Perseus, tasked with bringing back the head of the Gorgon Medusa, whose hair was a tangled mess of snakes (Metamorphoses, Book Four). Medusa was “so awful” that anyone who looked at her turned to stone (Wilk, 2000).

A popular figure in art, Medusa was frightfully depicted by 16th-century Italian painter Caravaggio. For a more comic rendition, see Brazilian painter Vik Muniz’s 1997 “Medusa Marinara,” at the Art Institute of Chicago.

And there is the Biblical story of Samson and treacherous Delilah, who pesters Samson into revealing that his hair is the source of his exceptional strength (Judges 16).

Some may also know O. Henry’s classic, The Gift of the Magi, in which a young impoverished couple sacrifices their most prized possessions— she, her hair, and he, his watch—to purchase Christmas gifts for each other, only to find that what they relinquish makes each spouse’s gift useless (1905).

In these stories, hair can be used symbolically to humiliate, enable sacrifice, terrify, endow strength, and profess love. What is it about this “special and cherished feature” (Buffoli et al, 2014) that we invest with such psychological meaning?

Hair, deriving from the epidermis, is unique to and a defining characteristic of mammals and not other animals. Externally, hair is composed of “thin, flexible tubes of dead, keratinized cells”—the hair shaft. Internally, there are living hair follicles, which grow in dynamic cycles of varying length that are dependent on where the hair is on the body as well as hormones, and an individual’s age, nutritional status, and environmental conditions (Buffoli et al.).

Hair’s main functions are to protect the skin and the eyes and provide temperature regulation (i.e., aids in perspiration evaporation; Stephens, 2022). Hair also increases the skin’s sensitivity to tactile, including sexual, stimulation. It no longer functions, though, as it does in other mammals, for insulation and camouflage (Randall, 2008).

Hair grows all over the body, except on our soles, palms of the hand, part of the lips, and parts of the external genitalia (Buffoli et al). Most of the hair on our body is fine, short, downy vellus hair (Stephens, 2022). When we are cold or anxious, this hair can “stand on end” and give us goosebumps (Randall).

Hair varies in length, diameter, and cross-sectional shape among people, as well as whether it is straight, curly, etc. A balance of different kinds of melanin pigment determines whether someone has blond, red, brown, or black hair. As we lose melanin pigment, our hair turns gray (Buffoli et al).

Impressively, hair is part of our body that is detachable, and unlike most other parts, almost magically, healthy hair regenerates—i.e., it grows back when cut—which gives it a spiritual dimension as well.

Most significantly, hair shapes our identity. It is a biological, physiological, and social marker of stages of our life. It changes as we age: Secondary hair develops at puberty, and thinning, graying, or even balding occurs later in life (Harlow and Lovén, 2022).

Although hairstyles change over time, as we saw in Fitzgerald’s story, culture often plays a considerable role in both prescribing and proscribing what is acceptable, including whether hair should be covered or even from what parts of the body hair should be removed.

Perhaps hair’s significance and symbolic power lie not only in its regenerative ability but also in that it creates boundaries (Smelik, 2015): between the body’s inside and out and between living material and dead; between human and animal, adult and pre-pubescent child, male and female, and health and illness.

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.