One scene in the 2013 film The Wolf of Wall Street became a “microcosm for the themes of debauchery and debasement” experienced by some women who worked in the financial world of the 1990s (Calautti, 2014). A young employee, amidst the sexually charged, orgiastic atmosphere of the entire trading floor, consents to have her head shorn publicly in exchange for the $10,000 she has promised to spend on breast implants.

Director Martin Scorsese’s camera lingers on this woman in the minutes after her ordeal. Grabbing clumps of her shaved hair, she looks dazed and confused and seems genuinely not to have appreciated what she had just allowed to happen.

The image, apparently based on true events, is extraordinarily disturbing and, though the situations are fundamentally different, calls to mind the public humiliation experienced by French women who were accused of consorting with German officials during the Occupation of WWII.

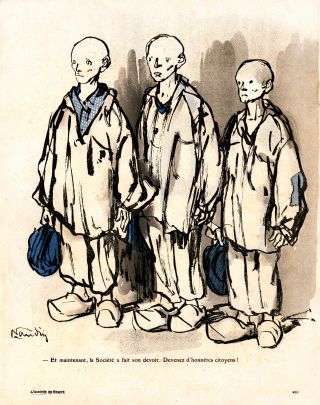

In “ritual acts of vengeance,” and with verbal taunts, jeers, and even physical violence, French Resistance fighters forcibly shaved the heads of these shamed women and paraded them through city streets (Deslandes, 2022; Easton, 2022). According to one source, at least 20,000 were known to have had their heads shaved as a “mark of retribution and moral outrage” amidst an “ugly carnival” atmosphere of “vicarious eroticism” (Beevor, 2009).

Many of these French women, whose husbands were away at war, had essentially no choice other than to make compromises to feed their families. Some were forced to house German soldiers, and still others were even falsely accused of collaboration horizontale (Beevor).

Ironically, it was the Nazis who shaved the heads of concentration camp prisoners to dehumanize, abuse, and humiliate their victims and deny them their hair, “an intrinsic marker of human identification” (Deslandes).

Throughout history, hair has been a “metaphor for social control” (Greenberg and Cody, 2022). The ancient Greeks and Romans shaved the heads of their slaves as punishment (Stewart, 2022) as they saw an exposed scalp as a “sign of degradation” (Giacometti, 1967).

During the Middle Ages, even Church dignitaries were subjected to public head shearing as punishment, authorized, for example, by 9th century Louis the Pious, son of Charlemagne.

Further, during the years of slavery in the U.S., hair was “weaponized as a tool of political oppression” such that the heads of slaves were shaved as punishment (Greensword, 2022; Greenberg and Cody).

The military has also used head-shaving to exact conformity and discipline among its recruits, creating a “sense of depersonalized individuals” and conveying a sense of authority for those in command (Freedman, 1994).

Since hair has been associated with aspects of femininity and seduction, some religions enforce strict codes about hair. Muslim women, for example, are expected to cover their hair and much of their bodies in a kind of “portable seclusion.” Further, Ultra-Orthodox and Hasidic women cover their natural hair with wigs (Greenberg and Cody).

There is often considerable social pressure for hair to conform to cultural standards, even though these standards may change over time. Well into the 20th century, blacks were made to feel their hair needed to be “conquered, tamed, and controlled” by straightening to conform to arbitrary, i.e., white, standards of beauty (Greensword).

Political hair is defined as “the ways hair is systematically used to determine, illustrate, and exemplify who is in charge, who may impose their will upon others, who are the oppressed…” (Greensword).

Sometimes, though, hairstyles can be used to thwart the predominant culture in what some have called the “tangles of resistance.” During the Black Liberation Movement, the Afro hairstyle became a “symbol of protest” (Johnson and Barber, 2022).

In recent years, dreadlocks, braids, and cornrows have reflected a means of expressing racial pride rather than reflecting protest (Tate, 2022).

Since hair can be styled like clothing but is also “corporeal like the body,” it “suggests both the public and private simultaneously” (Heaton, 2022).

Hair is often the first thing we notice about others, and it can have an “integral role in shaping our individual identity” (Wan and Donovan, 2018), particularly since “ours is a culture that places a premium on physical appearance” (Grimalt, 2005).

Nowhere does this become clearer than when we develop “appearance-altering conditions” (Grimalt), such as when hair loss is due to illness or the effects of treatment.

Those who undergo chemotherapy describe their loss of hair as a “public display of a newfound illness identity” (Wan and Donovan), “personifying the cancer diagnosis” (Boland et al., 2020), or “an advertisement” of their sick role (Freedman).

Though women can camouflage hair loss with a wig or scarf, some speak of not recognizing themselves in the mirror and seeing the expression in others’ eyes (Freedman). Cancer-related alopecia “not only affects how individuals perceive themselves but also how others perceive them” (Dua et al., 2017).

Chemotherapy or radiation-induced alopecia, which damages the hair follicles, affects about 65 percent of patients, though its severity can vary due to age, comorbidities, hormonal status, drug dosage, and administration (Boland et al.). It affects scalp hair diffusely or in patches (Dua et al.), but it can also affect eyebrows, eyelashes, and hair in other areas of the body (Freites-Martinez et al., 2019).

Many women consider hair loss the most traumatic side effect of treatment (Boland et al.), and some have poignantly described it as “more traumatic than the actual loss of a breast” (Freedman, 1994). Though it is usually reversible after a delay of 3 to 6 months post-treatment, this regrowth may differ in color or texture (Dua et al.). Persistent or permanent alopecia secondary to cancer treatment occurs in 30 percent of breast cancer survivors (Freites-Martinez et al.).

Hair loss can occur as a normal part of aging in both men and women and is not necessarily pathological, though the “balding industry” attempts to medicalize it (Jankowski and Frith, 2022). Men tend to lose more hair; for some, the loss is distressing enough to subject themselves to dubious remedies of trichoquackery (Kligman and Freeman, 1988).

Note: For my general discussion of hair, see my blog.

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.