The long-abandoned Beury Building at Broad Street and Erie Avenue is in the early stages of being redeveloped for a hotel and other uses by owner Shift Capital. | Photo: Michael Bixler

Seek out lists of historical neighborhoods to visit in Philadelphia and you’ll likely encounter the usual suspects: Old City and its charming alleyways, Center City and its various architecture, leafy “streetcar suburbs” in points west and northwest, with their summer estates and Victorian and Tudor-filled streets. But what about the intersection of Germantown Avenue, Erie Avenue, and Broad Street, deep in the heart of North Philadelphia and ringing the edge of the Nicetown-Tioga neighborhood? The area is more likely to be listed on a crime map on the local evening news than any list of “must-stops” for a typical visitor to Philadelphia. But should it be that way? Some are thinking differently.

The intersection and its corridor on Broad Street, located just north of Temple University Hospital, are at the vanguard of a new initiative created by the Philadelphia Historical Commission to reconsider the meaning of historic preservation. After years of planning, the Treasure Philly! initiative launched in August and will seek to explore new ways of capturing the cultural value of a neighborhood beyond the usual paradigm of building designation and historical placards. The area around Broad Street, Germantown Avenue, and Erie Avenue will be its pilot.

“The preservation field as a whole has been grappling with this a lot in the past few years,” said Shannon Garrison, Treasure Philly! program manager and historic preservation planner for the Historical Commission. “We’re beginning to think through, what specifically are we trying to protect? What is it about these places that makes them important? Is it just the buildings? Or, what about the people who live here currently? And dealing with issues of gentrification, development, and environmental threats. How does all this play into what we think of as preservation?”

The idea also holds value for community members like Amelia Price, corridor manager for Called to Serve, a community development corporation that operates out of Zion Baptist Church, located at Broad and Venango Streets. A long-time resident, Price is among those whose living memories include a very different time for the corridor, recalling a shopping district and family-oriented community in the mid-20th century, not the one where many live in fear of gun violence today.

Just as important is the future, which Price hopes that, through partnerships with the City like Treasure Philly!, will one day soon resemble the days of her youth. She and other advocates raise up the sankofa bird, a Ghanian symbol conveying the importance of remembering the past in order to progress. “His head is pointed toward his tail. Which means you can’t look forward unless you reach back and grab your roots,” Price explained.

Hidden Treasure

Dwight’s Barbecue at 3734 Germantown Avenue has been a neighborhood staple for decades. | Photo: Michael Bixler

Examining the historical and cultural landmarks of the eastern flank of Nicetown-Tioga is only part of a wider city effort to transform the area. In 2017, Mayor Jim Kenney launched a Broad, Germantown, and Erie Task Force. The City identified many areas for improvement. The corridor was among the 12 percent of city streets where 50 percent of traffic deaths and injuries happen and there was a need for more public spaces and business revitalization.

That same year, Mayor Kenney also launched the Philadelphia Historic Preservation Task Force to review the City’s policies and engage the public. Garrison said one of the main recommendations of the task force was to conduct a city-wide survey of potential historic assets. Martha Cross, now the acting deputy of the Department of Planning and Development, secured a $250,000 grant from the William Penn Foundation to help support the work. But there was a hitch. In addition to focusing on buildings, the foundation asked the City to take a look at how they document “intangible heritage and cultural resources beyond properties,” Garrison said.

The city was set to start work in early 2020, but was waylaid by the pandemic. “Once we got through the initial pandemic scramble, we realized we had a real opportunity with this project to take a step back and do something different,” said Garrison.

City preservation planners internally deliberated the best way forward and also engaged the ROZ Group, a Philadelphia-based strategic planning and marketing communications firm, to create a pilot effort examining how to best develop a methodology for identifying and preserving intangible resources.

Philadelphia isn’t alone in thinking through such challenges. Garrison said cities such as San Francisco and San Antonio have also been grappling with how to honor the history of an area when a key building may already have been demolished or what to do with tricky situations where the tension between past and present is evident. “This comes up a lot with legacy businesses. How do you allow for a family business that’s been around for generations to continue to operate when designating the building they operate in isn’t going to necessarily keep their business open?” Garrison said. “How do we look at these institutions more holistically?”

To make progress in Philadelphia, the task force formalized Treasure Philly! with its own website and eyed the Broad Street, Germantown Avenue, and Erie Avenue corridor for its pilot project. The City was already holding community meetings and making ties in the neighborhood through its infrastructure and business improvement efforts, so it made sense for the Historical Commission to piggyback. But that leaves the tricky part. How does one tangibly honor an intangible?

Building a Model Beyond Model Buildings

The former office of Pennsylvania State Representative Ruth Harper at 1427 Erie Avenue. Before taking office in 1977, she opened the Ruth Harper Modeling and Charm School there in 1963. | Photo: Michael Bixler

Garrison said the methodology is still very much an open question. Treasure Philly! launched this summer with large events held through September to bring in community members and talk with them about what they value about the neighborhood and its history. But bad luck and poor weather led to washouts, shifting the City’s plans to smaller walk-alongs in November.

“Our background is usually in architectural history, so if we walk a neighborhood only with other preservationists we’re only going to get one story,” Garrison said. “But if you walk that same neighborhood with somebody that has lived there for 50 years, they can reveal a whole other aspect of that neighborhood.”

At one two-hour community meeting Treasure Philly! held in August, that knowledge transfer had already began. Attendees talked about businesses they used to go to in the neighborhood, important neighborhood figures like the Reverend Leon Sullivan, and a charm school on the second floor of the legislative offices of Ruth Harper, a state representative who served the area from 1977 to 1992. She opened the Ruth Harper Modeling and Charm School in 1963. “Many women in the neighborhood would go there to learn their manners,” explained Garrison. “That was the first step, just letting people talk and listening.”

Another potential gem was the 3700 block of North 15th Street, which local residents recall was a regular candidate for “Most Beautiful Block” awards in the 1980s. Many of the homes, two and three-story rows with ornate cornices and bay windows, have small, square concrete flower boxes adjoining the front steps. Residents recalled warmly how they used to all be filled with flowers, and the Historical Commission was able to find an old newspaper article about the man who originally built them all for the block. “It’s something we might have noticed–why are there all these flower boxes–but maybe never would have connected the dots,” Garrison said.

Just how such community assets and memories could be honored is an open question. Preservations could use traditional methods like erecting preservation or historical markers or add to their toolkit with annual commemorations, oral history retention, or digital mapping. “A lot of the conversations have been, ‘What do we offer for people in the neighborhood to preserve these memories themselves?’” Garrison adds.

Concrete planters line the 3700 block of North 15th Street. Neighbors fondly remember the man that created them years ago to help beautify the area. | Photos: Michael Bixler

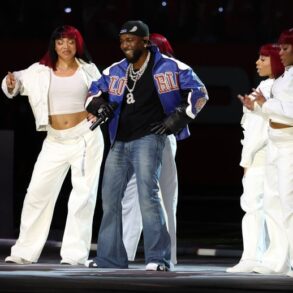

Price, with Called to Serve CDC, trends toward valuing the people of the neighborhood. Reverend Sullivan, an internationally-renowned civil rights leader and social activist, changed the lives of many during his time as pastor of Zion Baptist Church. Women’s basketball coach Dawn Staley, NBA players Markieff and Marcus Morris, and comedian and actor Kevin Hart’s mother have all called the congregation home.

Price said there are indeed architectural treasures to be had in the neighborhood, such as the towering, Art Deco Beury Building at Broad Street and Erie Avenue. Originally constructed in 1926 for the National Bank of North Philadelphia, it is perhaps best known currently for large vertical graffiti reading “Boner 4ever.” The building is set for redevelopment as a mixed-use hotel space, one of several promising projects for North Broad Street.

In this fashion, Price views the neighborhood’s history not as something to be put behind glass and admired at a distance, but actively leveraged for the purposes of revitalization. Through honoring the histories of local businesses like King of Pizza and Dwight’s BBQ, both multi-generational food joints, along with revitalizing standout buildings in the area, Price sees a path to return commerce to its former glory. Through public transit and infrastructure improvements, Price sees an opportunity to secure even more foot traffic for the business corridor.

Perhaps more than anything, by remembering and holding up the days when the neighborhood was family-oriented and filled with latchkey kids, and the community leaders who helped make it that way, Price believes Nicetown-Tioga can turn the page on its current challenging chapter. “With this Treasure Philly! thing we want people that’ve been on the corridor, and have lived in the community for 50, 60, 70 years, to tell their memories of the good old days,” Price said. “Just to tell the story so that the current generation will know that it wasn’t always like it is now. That there were some very great times, and it was filled with love.”

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.