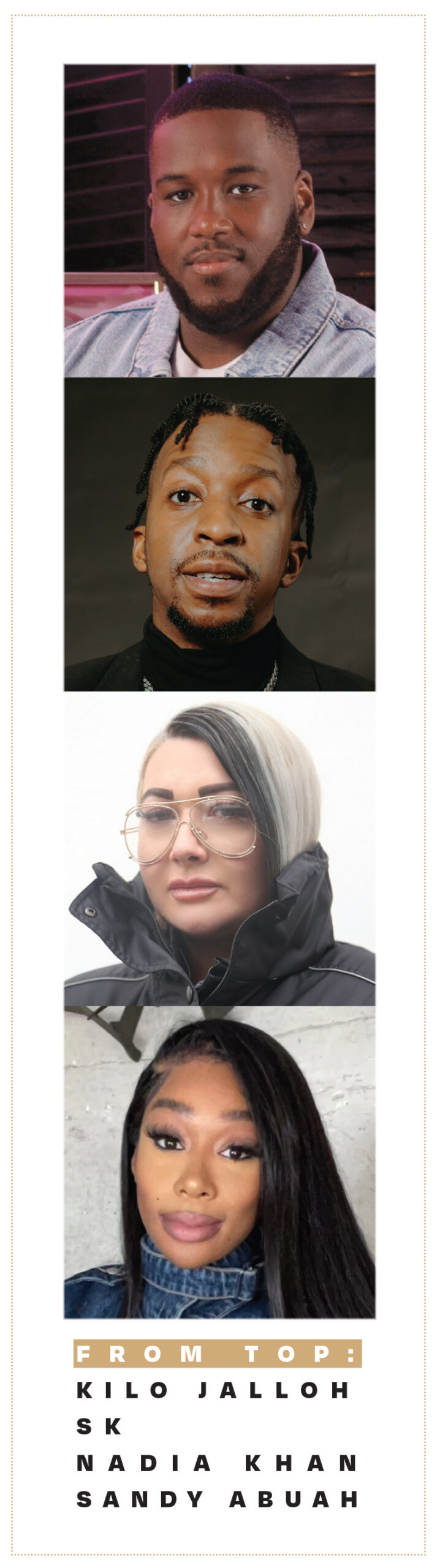

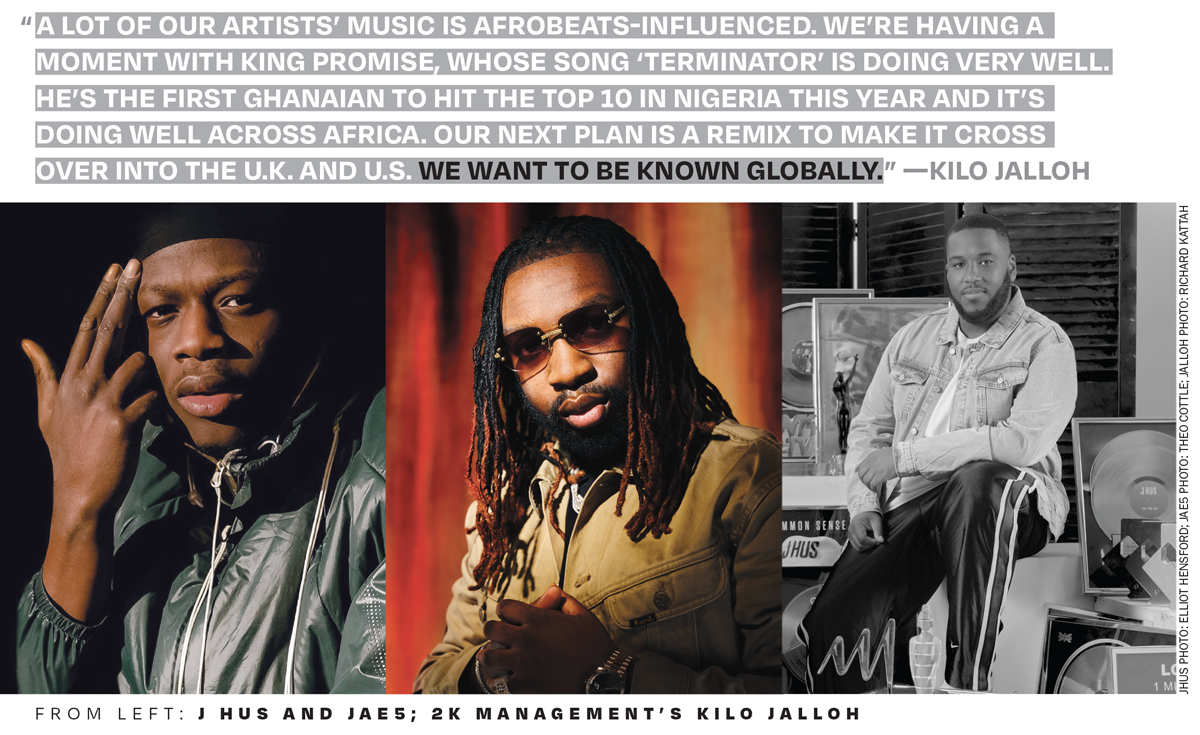

Kilo Jalloh presides over 2K Management alongside his brother, Moe Bah. The company manages J Hus, who hit #1 in the U.K. with his third album in July, and Grammy Award-winning producer Jae5, among others. 2K also has a label JV, 5K Records, with Sony Records, through which Jalloh and Bah signed Libianca last year. Her song “People” rose to #2 on the U.K. Official Singles Chart in April.

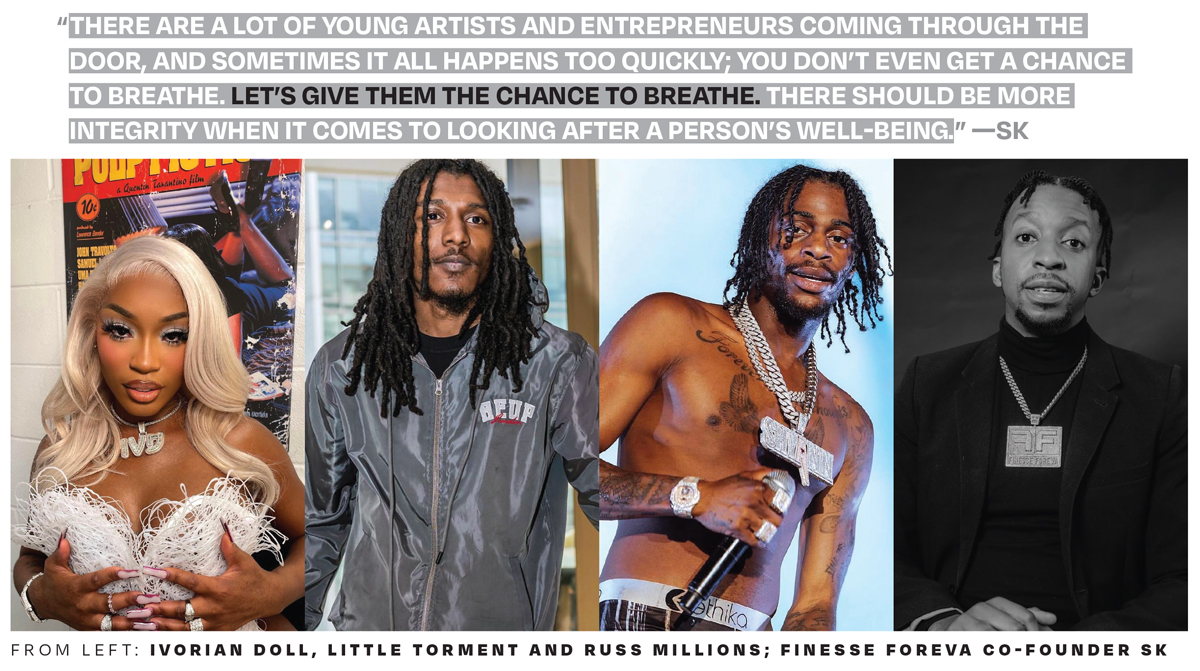

SK is co-founder of label and management company Finesse Foreva. Its management roster includes Russ Millions, who has three U.K. Top 10 hits to his name, including #1 “Body” with Tion Wayne. The rapper recently hit #3 in Turkey with “International”—a collaboration with local artist UZI. Others managed by SK include up-and-coming acts Ivorian Doll, Indie Amoi and Little Torment. SK is also an A&R consultant to September Management.

SK is co-founder of label and management company Finesse Foreva. Its management roster includes Russ Millions, who has three U.K. Top 10 hits to his name, including #1 “Body” with Tion Wayne. The rapper recently hit #3 in Turkey with “International”—a collaboration with local artist UZI. Others managed by SK include up-and-coming acts Ivorian Doll, Indie Amoi and Little Torment. SK is also an A&R consultant to September Management.

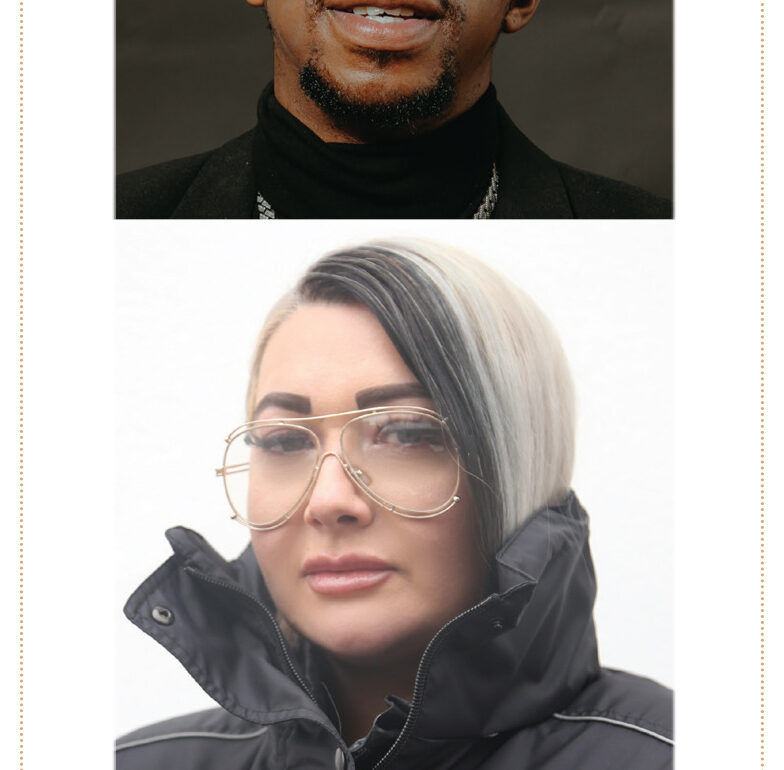

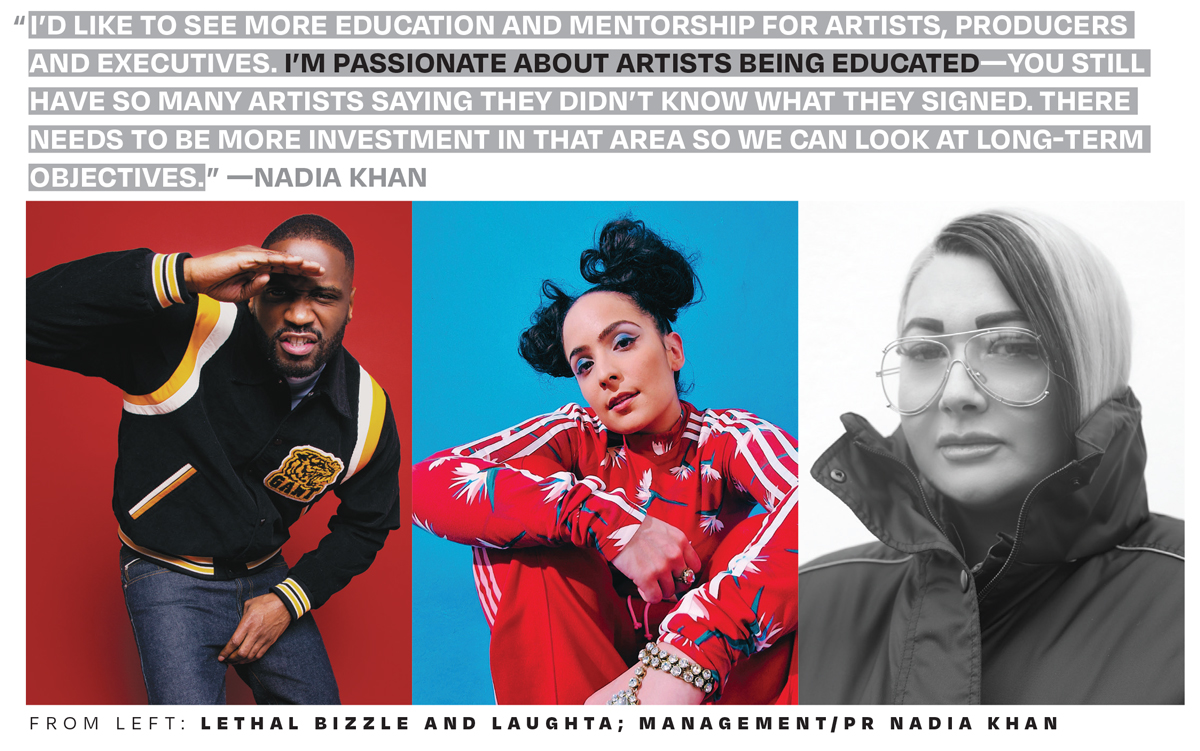

Nadia Khan has represented grime pioneer Lethal Bizzle for 18 years. He was her first management client after she started her music-industry career in PR. She has witnessed the growth of grime from the underground―when Bizzle’s debut single was banned due to its “aggressive” content―to the genre’s emergence into the mainstream. Khan also handles Lebanese rapper Laughta and leads the nonprofit Women in CTRL, which advances gender equality in the music industry.

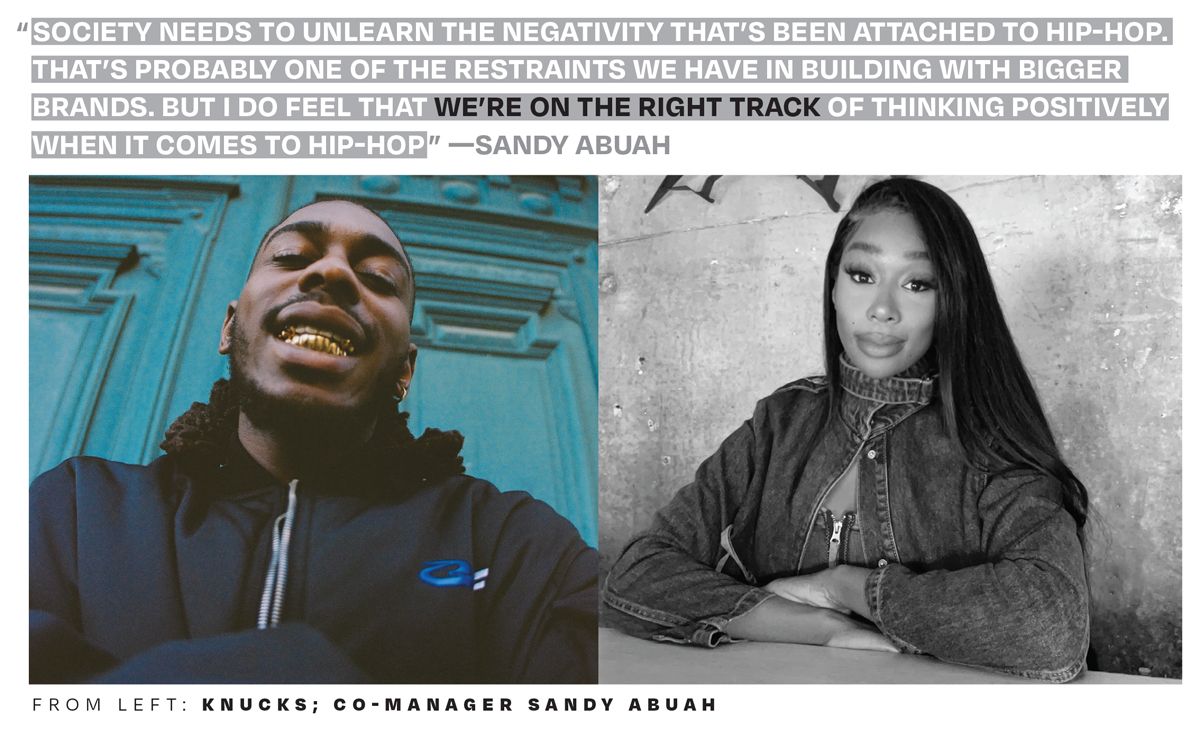

Sandy Abuah is co-manager of British rapper-producer Knucks alongside Mark Henry and Dion “Sincere” Lizzy. The trio oversees management company Tru Tribe. Abuah also began her industry career in PR, working with Brent Faiyaz and singer-songwriter Ama Lou, among others, before entering management. Knucks has focused on touring this year, including his first U.S. run. He released his debut album, ALPHA PLACE, in 2022. A second set is expected next year.

How would you characterize the health of the British hip-hop market?

Kilo Jalloh: It’s growing. When we started, hip-hop wasn’t a profitable business, but it’s turned into one. The streaming platforms have helped move it out of the underground. A lot of artists are making loads of money, and rightly so.

SK: It’s in a very healthy place, especially since surviving the pandemic, when live was shut off. That was a hard time. There are now more jobs and roles in the industry than ever before. The ecosystem has been built to a much higher level. You can also make music in your bedroom and market yourself. That’s amazing.

Nadia Khan: To see Central Cee and Dave have the longest-running #1 rap single in the U.K. [“Sprinter,” which occupied the top spot for 10 weeks] is a reflection of just how healthy the British rap scene is. It’s thriving and finally getting the mainstream recognition it’s deserved. Seeing that success reflected in the charts is really special. It’s the vision we hoped for when we started out.

Sandy Abuah: The health is as beautiful as it could be. It’s actually quite mind-blowing how palpable it is now, specifically in the U.S. It was previously just the likes of Skepta and Dizzee Rascal that conquered globally. Central Cee has been a great addition and has made a contribution to U.K. rap globally, opening doors for the likes of Knucks and other amazing talent. In 2022 Knucks and Central Cee were both nominated for BET Awards for Best International Flow. That was quite refreshing. Social media has played a massive part in the success of British hip-hop―it’s made the world closer.

What impact has the growth of hip-hop had on the grassroots scene?

KJ: When I was growing up, I didn’t think there was much opportunity. If you couldn’t rap, that was it. Now there are so many opportunities in the music industry. You don’t need to be a rapper; you can be an A&R or a producer, for example. There are a lot more artists coming through, which is allowing a lot more opportunities.

SK: It’s had a major impact, especially with genres like drill—in the U.K., we were the first company to get a #1 for a drill artist and producer [“Body”]. No one was invested in it before then. We’ve had the likes of Pop Smoke, who had a major impact in New York. In the U.K., we’ve had Russ Millions and DigDat, the first drill artist to chart. This so-called “street” music has evolved into a professional format. Drill, which originated in Chicago, had been demonized in the U.S., the U.K. and Europe. The fact that it’s getting represented in the culture is amazing, and it’s moved the culture worldwide. And that’s just one example.

NK: The pathways have been set, so it’s become a more viable business; if you want to start out as an artist, you can look to others who’ve paved the way and see those career opportunities. And how people release music has changed dramatically. The industry used to be the gatekeeper—the grime-scene pioneers, who could not rely on mainstream support, had to build independence. Now anyone and everyone can release music. Streaming has leveled that playing field, the barriers to entry. It does create some new challenges, though, because everything is so accessible; you see so many artists getting signed for a single that’s blowing up online, going viral, but how do you turn that profile into a sustainable career so you’re still here five or 10 years down the line?

SA: The U.K. sound had been neglected for a while and I feel we had a lot of doubt in our abilities. But the growth of hip-hop has given us hope that we can be our true authentic selves―you can be your own version of yourself and what you consider rap to be―and do anything. What’s exciting about the U.K. is that it’s not just grime; we’ve got different styles of rap coming out, and you’ve got R&B creeping up, too.

SA: The U.K. sound had been neglected for a while and I feel we had a lot of doubt in our abilities. But the growth of hip-hop has given us hope that we can be our true authentic selves―you can be your own version of yourself and what you consider rap to be―and do anything. What’s exciting about the U.K. is that it’s not just grime; we’ve got different styles of rap coming out, and you’ve got R&B creeping up, too.

Is there anything standing in the way of continued growth?

KJ: We’ve had a phase where TikTok has led the market—views, likes and re-creations have been equated with what’s a good song, rather than original artists putting time and effort into their music. I also feel we’re still suffering the effects of COVID-19, which has impacted hip-hop in particular; hip-hop lives in the clubs, DJ sets and parties, so it’s going to take some time before it properly comes back after the shutting down of those places for two years. When J Hus was coming up, I don’t think there was a university in the U.K. we didn’t perform at; a quick, 30-minute set at a club goes a long way toward building a fan base. Since COVID, I haven’t seen a lot of up-and-coming artists perform at shows that aren’t their own.

SK: It seems that numbers are being prioritized over talent and talent is being overlooked by a lot of labels. Before, they invested in the talent. I hope we’ll go back to investing in real talent and maintain the ethos that carried the culture forward. Without talent, there isn’t any hip-hop. Popularity can only take you so far.

SA: It really depends on how big your vision is. In recent years, you’ve been able to go anywhere, do whatever you decide to do. If you want to create a clothing line or get into tech as an artist, there are so many entry points into new areas of business through music. A lot of rappers are becoming actors, for example. And that’s only getting started. At the same time, it’s harder to crack the U.S. because it’s expensive to tour. Little Simz having to cancel her 2022 U.S. tour is an example of that.

NK: There’s definitely room for improvement. Mainstream outlets do not fully appreciate rap’s cultural significance because the route to market still goes through the underground, so it’s still seen as a niche. The success we’ve seen is built on the backs of independent artists doing the work; it’s not necessarily been from the investment of the U.K. music industry. And there’s still an issue with representation and diversity across the industry.

Independence and entrepreneurship are definitely a big part of British hip-hop culture, yet the level of support from the wider industry does seem to vary.

KJ: We’re fortunate because Moe and I are brothers, so whenever things aren’t going in our favor, we have each other’s back. Naturally, any person with an entrepreneurial mindset understands that it’s never going to be easy. Jae5 once said it’s like a relay race. You can’t do the full 200 meters alone; you have to do your one hundred meters, then take the baton and bring it home. There needs to be incentive for all parties to invest fully.

SK: The industry gives you room to be your own boss. But what I think needs to be done better is offering more chances to young and upcoming entrepreneurs, A&R managers and label execs. The music world isn’t prejudiced against young people—it’s about what you know, your capabilities and your actions. You could be 15 years old and great at finding talent. So you should have the opportunity to get an intern role to showcase that and from there, create your own empire. That’s how the culture goes—it’s a domino effect. I’d also like to see more media coverage on the business side, which can provide a sense of achievement and encouragement to others coming up.

NK: The wider music industry has become more receptive to independence and the entrepreneurial spirit. You see independent artists, labels and managers getting more recognition. You can also see more major labels willing to collaborate with them compared to how it was a decade ago or when I started out 20 years ago. But I still feel there’s work to be done in creating fair deals and opportunities for independent artists. A lot of it now seems to be, “OK, you’ve built these platforms. Now go and create those numbers, generate that hype all by yourself.” There could be a lot more investment in artist development instead of artists having to do all that grassroots groundwork themselves. Artist development is crucial to continuing the growth of the genre.

SA: I’d like to see a lot more alignment with brands and partnerships. For artists like Rihanna, with Fenty Beauty and Fenty everything, the entry point was music, and she’s been able to build an empire. I’d love to see that in U.K. rap. Skepta is on a great trajectory at the moment with his Mains fashion line and his DJ stuff, bullet-pointing who he is as a person, not just as a rapper.

Does hip-hop get the respect it deserves in the U.K.? And if so, is that reflected in business deals?

KJ: Hip-hop has come a long way. It’s actually doing better than all the other genres at this moment. When it comes to deals, you have to understand what you’re doing, surround yourself with people you trust who understand the business, who have your best interests at heart. I wouldn’t say the industry’s agenda is to sell hip-hop short. But I do think we’ve got to educate ourselves to understand what deals work for us and not compare what we’re getting with somebody else’s deal.

SK: I think we are getting respect now because we move the culture. It starts with us; without us representing, the wider industry wouldn’t understand hip-hop. It’s good that we’re getting fair deals and performing on big stages. Stormzy headlining Glastonbury would never have happened a couple of years before. People are listening to our music, so the industry can’t shut the door on us.

NK: There’s a blank check for artists who’ve proven themselves with the numbers, but you have to have those numbers before you can gain that respect. I speak to a lot of people who work at major labels, and I see they’re fighting for budgets and resources for their Black, rap or drill artists, for them to be taken seriously, nurtured, developed and invested in. That changes once you have that viral moment. And the success helps strengthen the position of artists; that’s the way the industry works—once you see the results, labels will try to replicate that, try to create their own Central Cees or Daves, which creates more opportunities for other artists to get signed.

SA: I wouldn’t say the level of respect for hip-hop is equal to that of other genres. Society needs to unlearn the negativity that’s been attached to hip-hop. That’s probably one of the restraints we have in building with bigger brands. But I do feel that we’re on the right track of thinking positively when it comes to hip-hop.

What else would you like to see change to further strengthen the British hip-hop market?

KJ: I’d like to see a bit more patience. A lot of artists do get time to develop, but hip-hop can be judged too early. It takes time—especially with the acts coming through now, who are younger. They need to discover their sound, their image or their brand, what works for them.

SK: I’d like to see more mental-health support. Every label or management company should have a space where clients can express themselves, vent or just have a conversation outside music. This industry does take a toll on you. I’ve had times before we got the #1 when I just wanted to give up. Luckily for me, I’ve had business partners, but some people don’t have those. There are a lot of young artists and entrepreneurs coming through the door, and sometimes it all happens too quickly; you don’t even get a chance to breathe. Let’s give them the chance to breathe. There should be more integrity when it comes to looking after a person’s well-being.

NK: In addition to investment in artist development, I’d like to see more education and mentorship for artists, producers and executives. I’m passionate about artists being educated about business contracts, terms and understanding the business overall―you still have so many artists saying they didn’t know what they signed. There needs to be more investment in this area so we can look at long-term objectives. I’m talking about longevity; “How are you still relevant? How are you still here five, 10 years later?” I’m also talking about building independent businesses. That doesn’t mean not working with major labels; it just means making the decisions about the deals that are going to help advance your career.

SA: I’d like to see a more global approach to U.K. rap. The strategy in the U.K. is solidified, but there needs to be more thought, energy and marketing costs put towards extending that globally. It’s about having micro teams in these territories that are able to work with U.K. acts and blow them up. I still think it’s very niche; you only find a few professionals who know how to deal with crossover acts.

How important are global markets, including the U.S.?

KJ: With the success of the Libianca record, our focus is working with international teams to tap into other markets. Having something connect outside your territory is a good feeling. A lot of our artists’ music is Afrobeats-influenced. We’re having a moment with King Promise, whose song “Terminator” is doing very well. He’s the first Ghanaian to hit the Top 10 in Nigeria this year and it’s doing well across Africa. Our next plan is a remix to make it cross over into the U.K. and U.S. We don’t focus on one market; we want to be known globally.

SK: The U.S. market is very important, but we’re in a time when all the markets matter. Africa is a dominant market right now. Burna Boy being the first Afrobeats artist to get a #1 was a massive achievement. It’s a more level playing field. I’m Nigerian myself and I feel ashamed that I haven’t had an Afrobeats artist, so Africa is one place I’m looking to. Another place I’m looking to is Europe, which has a massive rap and hip-hop culture.

NK: It’s different with each artist. With Lethal Bizzle, having worked with him for 18 years, I’ve seen different sides of it. At the beginning, the labels―even labels we were signed to―wouldn’t give us the resources and there would be zero interest from international teams. Now we’re seeing success, and it’s opened a lot more doors. Grime was very niche and underground, but with social media, it’s opened up and become a global market. With Laughta, she’s Lebanese so her project is definitely international. She’s got a real British flavor but she brings her Arab heritage in, and there’s a huge Arab diaspora across the world that’s growing. Markets across the Middle East are really important for her new music, but we were also recently in Japan and South Korea.

SA: We want to tap into different parts of the world, not just the States and Australia, as long as there’s strategy behind what we’re doing. You have to start at grassroots level. Our thing is doing it all together; if you do each of the territories simultaneously, it all grows together.

How big is the appetite for British hip-hop in other markets?

KJ: It’s subject to the artist, but Scandinavia takes well to U.K. rap, and in the U.S., there are a few people breaking through. We’re yet to go to the States with J Hus, but there is interest for shows and features. As the U.S. is such a big market, you’ve got to be on the ground. Those kinds of opportunities don’t come through social media or speaking on the phone; it’s about being there and building relationships. You see it working with Central Cee, Skepta and Dave, who are always out there, and Giggs just did a song with Diddy. There’s an appetite for it, but you’ve got to be up for traveling and understand you’re not going to be the biggest in the room at times. There’s appetite in wider Europe as well and Africa. When I look at where the fan base is building for the artists we’re working with, a lot is being built out of West Africa.

SK: We’ve got a tune with Russ Millions and UZI going crazy in Turkey; it’s gone to #3 and 70% of the streaming was from Turkey. You see people doing stadiums in Australia. It’s phenomenal. Before, it was just the little old U.K., but now the music is worldwide. That’s the power of social media―you could be building a fan base in a whole other area you don’t even know. That’s something I find so fascinating when we do live shows. I did a show with Russ in Albania, and I was thinking, “They aren’t going to know these songs here,” but it was absolutely crazy. I was, like, “How do they even know his music?”

NK: U.K. hip-hop has become a global phenomenon. I’ve done a lot of traveling this year and no matter where I’ve been, from the U.S. and Europe to the Middle East and South Korea, British rap music is a massive export. Seeing these big chart hits transcend borders is strengthening the value of British rap. So the music does have cultural significance overseas, which demonstrates the level of opportunity. But it’s quite difficult to break an act internationally. You have to invest the time and resources, whether that’s building a team, going out on the road or collaborating.

SA: We did a tour in January and February in Australia and it was crazy to see the world in a different time zone and how it gravitated toward rap and the U.K. sound. Knucks has had crowds of people. He sold out his two shows; he did the Laneway Festival… I didn’t know that they appreciate U.K. rap over there the way they do. That’s somewhere we really want to cultivate and spend more time in.

How do you see the British hip-hop market evolving in the future?

KJ: There’s a lot of sample rap going on at the moment; artists and A&Rs are tuning into old-school R&B or hip-hop songs, giving them new life. We may see more of that. And artists working globally—Unknown T has collaborations in Paris and Headie One hit the Top 20 in Germany with a feature—will continue.

SK: We’re just going to get bigger. Central Cee and his team have done an absolutely amazing job infiltrating the U.S. market. There are also going to be more jobs, more opportunities for our executives, and the music is going to get even better. And it’s not just the music; fashion is moving along with it as well. Our whole ecosystem is moving across the globe.

NK: British rap music has been very London-centric, but we’re going to see a lot more regional rap artists and scenes making noise. I’m excited about that. There are so many people building and nurturing independent scenes regionally―there’s a lot of talent on the way.

SA: I think it will be about connecting with one another and collaborating across other genres: R&B, pop, Afrobeats… That would be an amazing way to strengthen British rap. It’s about being open, and not just to the U.S. I feel like we haven’t capitalized much in Asia. I just came back from South Korea―I was stunned by all the hip-hop subcultures.

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.