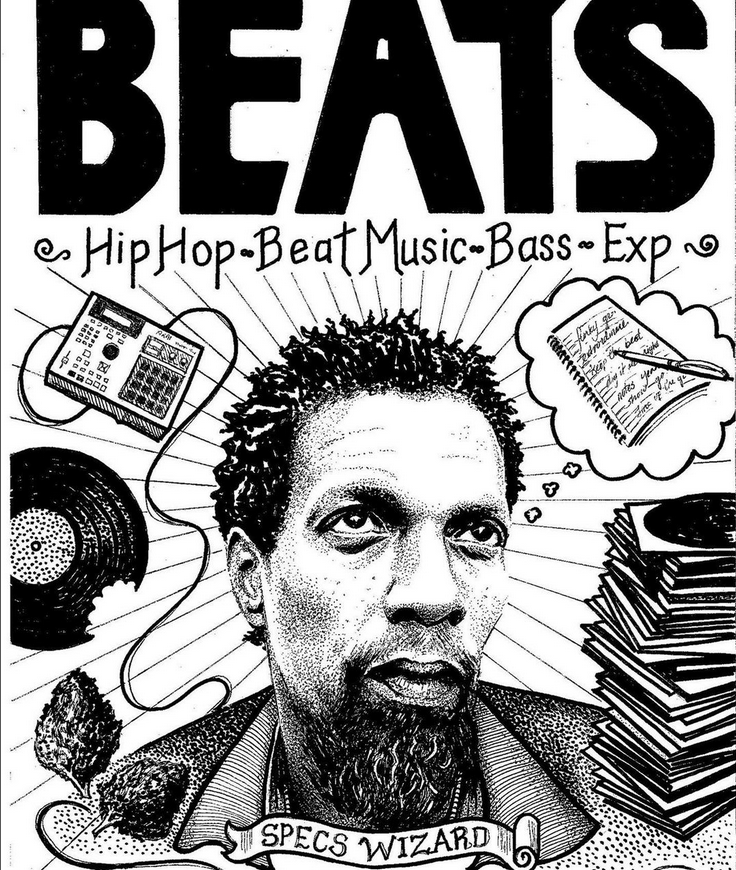

“You get treated like you’re invisible here,” says MC Specs, the so-called “Holy Ghost of NW Hip-Hop,” and co-founder of the legendary Elevators. “It’s a theme in a lot of my songs. It’s been a thing in Seattle for a long time.”

In the summer of 1993, Northwest rock groups Nirvana and Pearl Jam reigned over the country’s Billboard charts. International mania for Grunge brought massive media attention to the Northwest. Tucked away under the sea of flannel and distorted guitars, in Seattle’s often overlooked hip-hop scene, a hidden gem emerged—the Elevators.

“We’re not just all Alice in Chains and Soundgarden here. They’re fat and all, but wake the fuck up to hip-hop as well. Prime example is the Elevators,” wrote Mike ‘Clarkman’ Clark, editor of the Flavor.

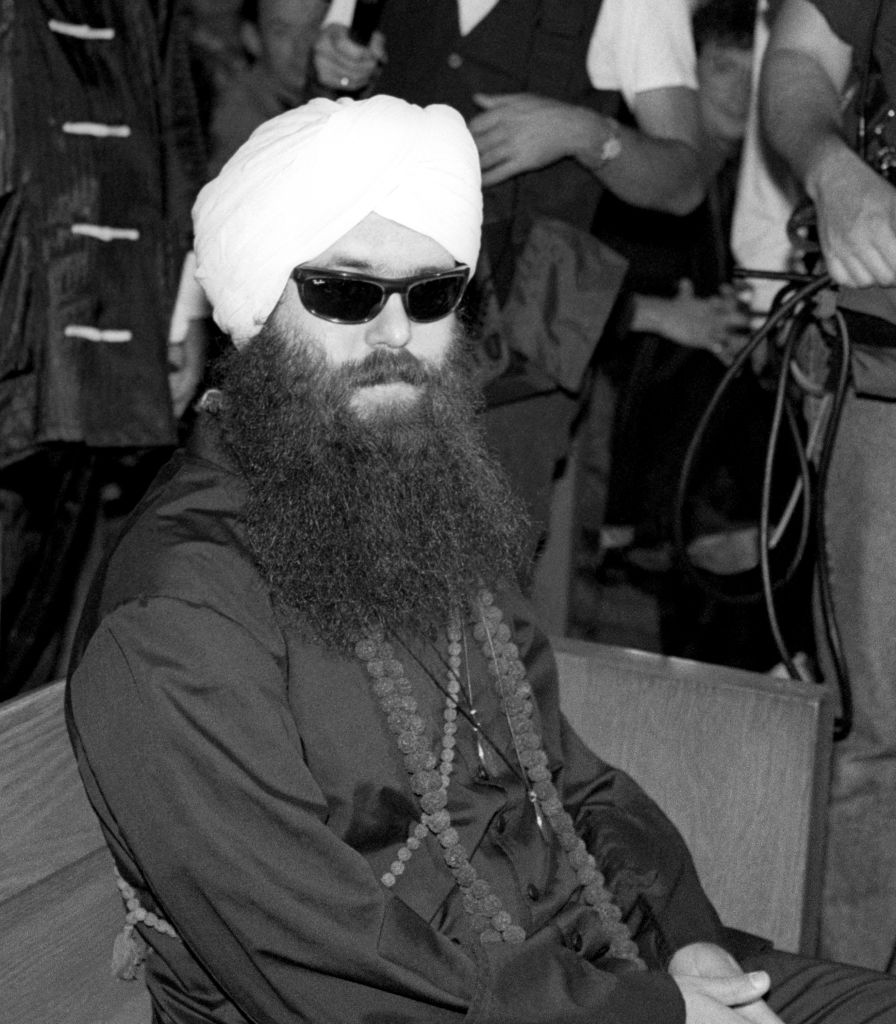

Mike ‘Clarkman’ Clark

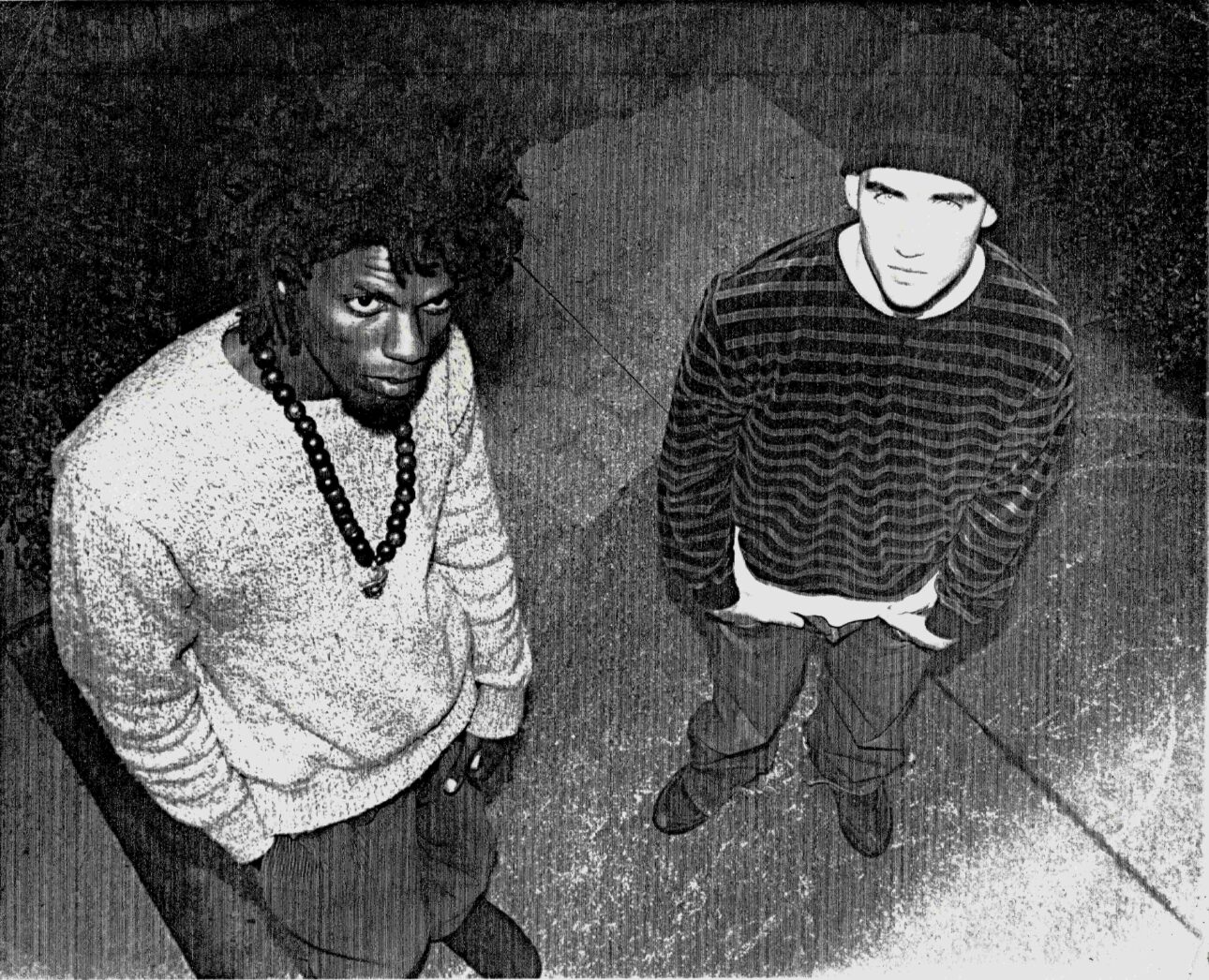

“These kids are straight-up East Coast flavor. E-Sharp and Specs make up the Elevators, and yo, this is like fuckin’ ‘Jazz Thing’ part 2 when you hear this shit,” Clarkman wrote.

The enigmatic duo captured the attention of the Flavor, a monthly American hip-hop magazine based in Seattle between 1992 and 1995. They showcased the finest acts in underground rap. They were the first to recognize the immense talent of a young Nas and feature him on their cover. They interviewed now-legendary groups like A Tribe Called Quest, the Pharcyde, and De La Soul. The Flavor mentions Elevators in their pages six times over the span of a single year.

Elevators flourished for less than a year before disappearing into obscurity. They only released six songs, which appear on the meticulously recorded and untitled ‘Elevators tape.’ Specs and E-Sharp individually hand-dubbed the cassettes and personally sold them on the bustling ‘Ave’ in Seattle’s University District. Each one is adorned with a unique cover. They’ve become treasured artifacts, sought after by collectors. The tape holds a mere 16 minutes of hip-hop, but the raw intensity of the music still resonates with fans even after three decades.

“At the time, it was mandatory to have this release,” says DeVon Manier, head of longtime Seattle record label Sportn’ Life Music Group. “The Elevators tape is a definite town classic.”

“Elevators were unforgettable,” reminisces Rawi, a rapper from rivals Six In The Clip. “Specs was completely original. I loved the group’s vibe. Their demeanor was super chill. They made authentic, truthful hip-hop.”

Now, 30 years later, I find myself at Hattie’s Hat, a historic Seattle bar, sitting opposite M.C. Specs himself. “I felt like Elevators was about to become something. We had a lot of attention on us. Everyone was calling us Seattle’s answer to Gang Starr. We were heroes out here.”

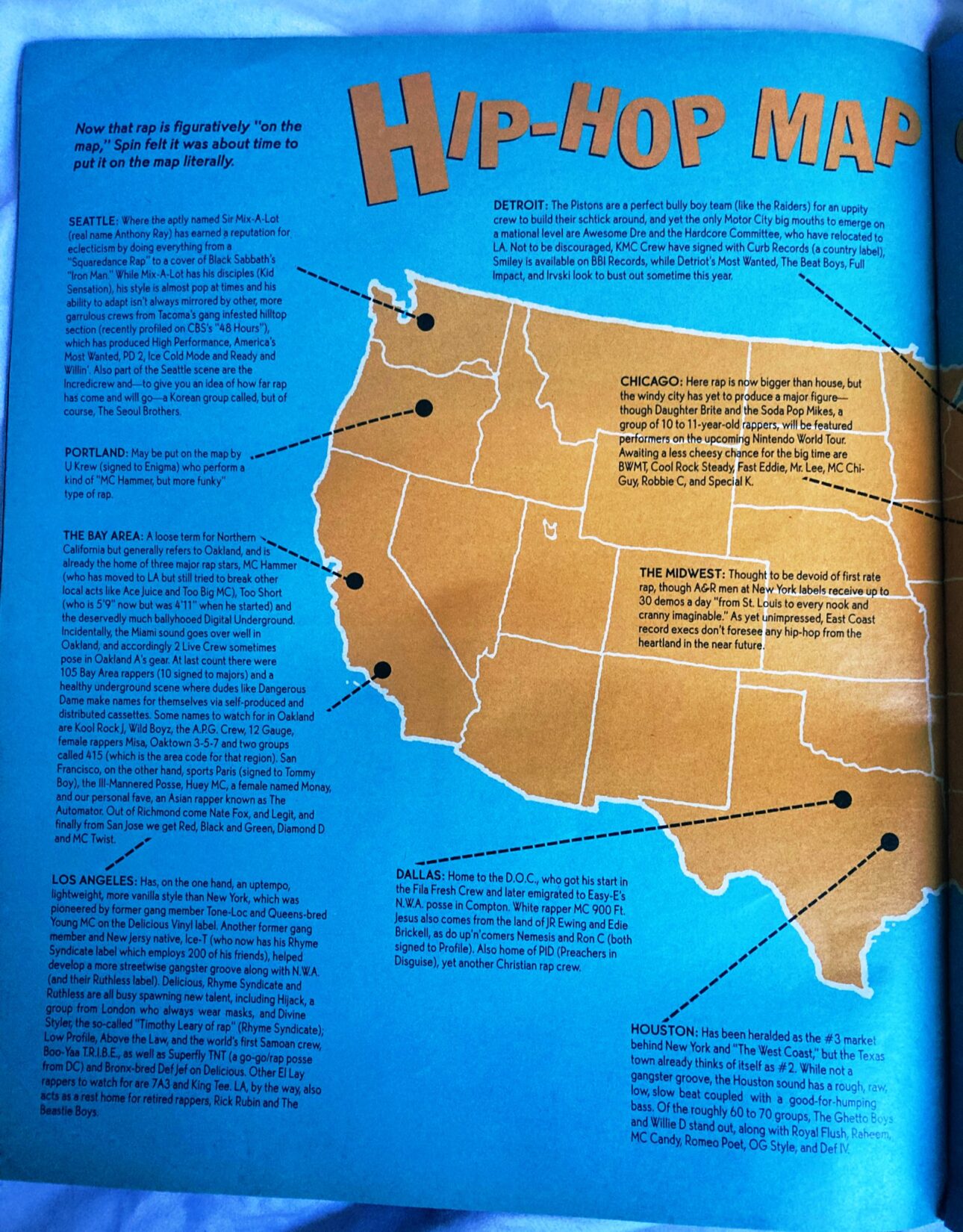

In June 1990, SPIN published “The Hip-Hop Map,” an article that solidified Seattle’s stature as a thriving hip-hop hotbed. The city appeared alongside emerging rap scenes in Chicago, Detroit, and The Bay Area.

Northwest rap label NastyMix was a hip-hop hit machine. Sir Mix-A-Lot’s early singles, “Posse on Broadway,” “Iron Man,” and “My Hooptie” were on MTV, BET, radio, and the charts. When NastyMix added High Performance, Kid Sensation, and Criminal Nation to their roster, they, too, had music videos on TV and hits on national radio. The sounds of the Central District and Hilltop rang out across the nation.

NastyMix brought Fab 5 Freddie and Yo! MTV Raps to Washington State for the first time. When Sir Mix-A-Lot’s first album SWASS went gold, MTV came back to celebrate, and NastyMix took them to Dick’s Drive-In.

Mix then achieved his most audacious feat yet, chopping up Prince’s “Batdance,” the number-one song of the summer, while it was still in the charts. His version, “Beepers” shot to number two on the Hot Rap list, proving he was a force to be reckoned with.

“It didn’t make deep dives into the culture,” says Specs as he shakes his head. “You slap down some Funkadelic or Parliament sample and put ‘berr eeee’ on it. You make it commercially viable to make money off people who aren’t into the culture.” Elevators weren’t agreeing with that.

SPIN’s Hip-Hop Map includes a few other, less familiar names grinding it out in Washington State: Incredicrew, P-D2, Ice Cold Mode, Ready and Willin’, and the Seoul Brothers. “I was performing with all these people,” says Specs, “I knew a hundred different groups back then. Only a few are gonna get through.”

The man who would become M.C. Specs, Michael Hall, was born in 1968 and raised in West Seattle. He’s five years younger than Sir Mix-A-Lot. He started scribbling his stage name in graffiti around town as a teen. “I started dabbling with my first sampler in ‘88 and I really got into it.”

Top Notch Productions, his first group, had a song on the local radio show Rap Attack in 1989. The trio of Specs, DJ Wacko, and FE3 got into an argument about copyright infringement. “Sampling is a commentary on recorded music,” Specs argued. “This is going to be an art form. I want to do this.” They disagreed, and so he left the group.

He heard E-Sharp on Rap Attack, not long after. “I loved his song. It had the sound that I was trying to go toward.” He tracked down E-Sharp at a show and they started hanging out. They could relate to one another. “It was a deeper sense of hip-hop,” adds Specs.

In 1990, Sir Mix-A-Lot announced he was leaving NastyMix to start a new Northwest rap label. “My goal is to solidify the Seattle base,” he said to Northwest music newspaper the Rocket. He had backing from Def American. “I feel like the dope man — feed Rick Rubin a little and when he gets hooked he’s gonna want more.” The NastyMix owners threatened breach of contract and Mix countersued for unpaid royalties. The divorce was messy.

As a result, while Nirvana, Pearl Jam, and Soundgarden started to commandeer the airwaves, Mix was fighting for his independence in court. His battle cost a reported $1.2 million to untangle, nearly bankrupting both parties. Mix ultimately won his exit and his publishing rights. NastyMix limped along and closed the next year.

The NastyMix courtroom drama and the sudden dominance of grunge—both at the same time—left little space for other rap acts. In 1991, The Source picked local group Brothers of The Same Mind as the top unsigned act in the country. The Flavor asked them if their hometown was a blessing or a curse.

“We have to deal with the stigma of Sir Mix-A-Lot,” replied Sin-Q, one of the group’s emcees. ”Everyone looks toward Seattle and thinks the only thing coming out of here is Mix and his crew.”

Brothers of the Same MInd

Sentiment started to creep into local media that hip-hop, like disco before it, was a trend that was simply played out. The Rocket dismissed Kid Sensation’s new album as old news and all but stopped covering the genre as the grunge tsunami hit.

“Seattle kinda had a foot on it,” says Specs. There was also the Teen Dance Ordinance to contend with, a curfew law used by the city to shut down all-ages parties and hip-hop events. “They were trying to act like the scene doesn’t exist. No, it does, and it’s pretty damn good.”

When the Flavor reviewed the Elevator tape, they argued it represented a way forward. “The Seattle hip-hop scene has been looked upon as a joke for too long,” their review begins, “But these two heads, E-Sharp and M.C. Specs, have come together to form Elevators, a group whose mental boundaries obviously go beyond the boundaries of ‘Sea-Town.’”

As NastyMix fell apart, its artists fought it out in public. In their “Takin’ Over Shit” video, High Performance trash the NastyMix offices and murders an actor dressed as Mix-A-Lot. Kid Sensation broke down the formula for not getting screwed by the man on his song “Dollars and Sense.” Criminal Nation unloaded the subwoofer-shaker “Somethin 4 Yr Trunk,” expressing their rage at getting ripped off by saying “fuck you” to everyone. The song also encourages listeners to go buy their album: “If you’re bumping this jam and you like it, tell your homie to take his Black ass to the store and go buy it, ‘cause it cuts down sales when you dub, and you dub, and you dub, and your tape sounds like shit.”

“A lot of people have cassettes,” said NastyMix promotions head Nasty Nes in 1992 as everything was falling apart. “But do you want to make a hundred bucks selling 50 tapes or do you want to make a million dollars selling a million records worldwide?”

“Being honest to yourself is actually very valuable,” Specs retorts. His definition of success is different. ”Being yourself is like having a superpower. You have this stuff that nobody else has. You have to hold on to it.” He pauses. “You know, sometimes it works for people. Sometimes people get payments off being their weird self.”

Sir Mix-A-Lot estimates he’s earned over $100 million in royalties from the song “Baby Got Back.” The man who would become Sir Mix-A-Lot, Anthony Ray, was born in 1963, one year after the World’s Fair declared Seattle an important and influential city of tomorrow. Raised in the city’s Central District, he still lives in the Seattle area today.

Sir Mix-A-Lot’s earliest records are a trio of EPs. They’re not officially online anywhere, either. Influenced by German techno pioneer Kraftwerk, these records are playful and nerdy. He itemizes his recording gear, explains how to use bass oscillators to improve drum sounds, and claims he will “demolish DJs with computer technology.” The credits say “All selections are written, arranged, programmed, performed, produced, and engineered by Sir Mix-A-Lot.” He did it all himself.

“I would love to do cool shit with Mix-A-Lot’s gear,” says Specs. “It made his songs sound different from everyone else’s.”

Mix-A-Lot’s first global smash was the gonzo “Square Dance Rap.” In 1986, he flew to England and performed the song alongside Dr. Dre & World Class Wreckin’ Cru, Grandmaster Flash, and Afrika Bambaata at Wembley Arena.

“It’s almost like thievery,” said Mix when asked by the Rocket to contemplate his early career. “Even if rap hadn’t become popular, we’d be doing the same thing. We’re rebels and kids like rebels. Even old guys who want to feel young go out and buy rap.”

When he started work on his third album, Mix-A-Lot was finally free from NastyMix. The record that would become Mack Daddy is full of Washington flavor. Garfield High School, Rainier Beach, King County cops, Sea-Tac, and Bellevue all make appearances throughout his capers. He saw the project as an opportunity to highlight the whole scene, with songs like “Seattle Ain’t Bullshitting” shouting out a long list of local underground acts including Brothers of the Same Mind, E-Dawg, J-1, Kazy-D, L.S.R., and P-D2 alongside old labelmates Criminal Nation, Kid Sensation, and High Performance.

He recorded the album at home in a high-tech studio adjacent to his dining room. He originally cut “Baby Got Back” from the record. He thought it was filler material. Rick Rubin convinced him to keep it, and they released it as a single.

On May 7, 1992, Mix-A-Lot dropped a song that would knock the world off its axis. “I Like Big Butts” is the most likely rap song to be played at your nephew’s wedding in August. It’s a silly, funny crowd-pleaser. “Look at her butt!” was flipped by Nikki Minaj into “Anaconda” in 2014. It’s been referenced by Eminem, Lil Wayne, Friends, and Bojack Horseman. When the BeyHive went looking for the identity of “Becky,” they found their way back to Mix, too. The lasting cultural impact of this one song—and its corporate, commercial appropriation over 30 years—is perhaps best found on cardboard boxes from Amazon that in 2023 are adorned with the text, “Oh. My. God. Becky. Look. At. This. Box.”

The aftershocks of Sir Mix-A-Lot’s staggering success still resonate through Seattle rap today. On BLK GLD, Porter Ray dreams of driving Lamborghinis and “money like Mix-A-Lot.” Guayaba’s Fantasmagoria opens with the verse “All you see in me is a Bremolo who still lives at home.” In 2021, rapper Marshall Hugh recreated the “Baby Got Back” cover artwork to promote his upcoming concert.

“Baby Got Back” won the 1993 Grammy Award for Best Rap Solo Performance. The following year, Seattle-born Ishmael Butler, in the guise of Butterfly from Digable Planets, won the 1994 Grammy for Best Rap Performance by Duo or Group. People rarely comment on how, during the so-called “Grunge years,” Seattle’s rap artists too were being recognized by mainstream America.

The two back-to-back Grammy wins were interpreted quite differently by their respective winners. When he’s appeared on live streams and Zoom events, Mix sits proudly in front of a wall of platinum records and trophies so vast that it goes off the edges of the screen. Butterfly reflected on his win in the 25th-anniversary liner notes for Digable’s Reachin’ (A New Refutation of Time and Space), saying “Back then, if you won a Grammy, it was like you was a sucka… It didn’t mean nothing good to hip-hop.”

Local artists envied Sir Mix-A-Lot’s success and fame but also sought to emulate his example. He proved you could do it all yourself, be your own weird self, start your own label, and win. “Mix has had a tremendous career. Comin’ from Seattle is not an excuse,” said Incredicrew’s Danny Dee (aka Supreme) to the Flavor. “You’re here. Learn to deal with it.”

Seattle rapper Jay Skee signed with Mix’s brand new label for a minute before seeing the bigger opportunity and left to start his own. He wanted to “exercise his right to speak how he wants to speak with catching slack from a major label,” according to reporting in the Flavor.

Nirvana label Geffen set up a new hip-hop department and handed a contract to Seattle rap group Ghetto Chilldren. The duo of B-Self and Vitamin D were on the come-up. “We got signed to Geffen along with Beck and The Roots,” said Vitamin D recently on The Chop Shop podcast. “We’d already made our songs to my beats. Geffen wanted us to be produced by the Dust Brothers. It didn’t work out, obviously.” They walked away and started their own label, Tribal Music.

Macklemore raps “My greatest teachers: B-Self and Vita,” on “The Town.” Even Seattle’s Grammy-winning “Thrift Shop” star is self-released and independent.

“I wanted a record deal. Of course, I wanted money behind what we were doing,” says Specs. “But I was never willing to give up vision or artistic integrity. We didn’t want anyone telling us what to do.”

The Flavor ran a two-page profile on Elevators in 1993. Editor Tracy Armour asked E-Sharp how the group hoped to be remembered in 20 or 30 years. “Our shit was rugged. We had beats and rugged lyrics,” he replies.

After a white-hot blaze of hype, Elevators disappeared.

In the golden age of MP3 blogs, circa 2010, Bring That Beat Back specialized in posting digital rips of out-of-print vinyl and obscure hip-hop cassettes from the early ‘90s. Northwest blogger Jack Devo would dig through thrift shops, uncover treasure, and post downloadable MP3s.

“I vividly remember the night first I heard the home-recorded Elevators cassette,” he writes, describing the one and only time he’d listened to the tape. He was hanging with friends and one had scored a copy. “Digable’s Blowout was unceremoniously ejected, and the tape went in. The beats were rough and low-fi. The vocals were quiet but confidently conscious. It was next level. Brief but memorable.”

The blogger included the tape in a list of “Shit I’m Looking For” on the sidebar of his blog. One day, an MP3 rip of the storied cassette arrived in his email. “Elevators effectively moved Seattle forward beyond the 808-heavy party tracks of Sir Mix-A-Lot,” he wrote in a post accompanying the downloadable files. “They established the quietly jazzy and lyrically substantial aesthetic that eventually put Seattle on the underground hip-hop map. Elevators’ influence is indelible. Give Specs One and E-Sharp a serious head nod.”

Bring That Beat Back went offline in 2018, and the Elevators tape disappeared once again.

I track down Novocaine132, a hip-hop writer from the ‘90s. These days, he posts “Top Ten Songs” videos on YouTube that celebrate ‘90s rap from the Northwest, highlighting underground artists such as Ghetto Chilldren, Source of Labor, Spyc-E, and Footprints. He’s done a video for Specs, too. His number one Specs song is “Elevator Music” from the Elevators tape. He says to me, “Specs is a renaissance man and rap pioneer.”

He recently revived Ever Rap, a local hip-hop label from the early days of the scene. Since 2019, Ever Rap has been remastering and releasing vinyl records by early Seattle rap acts, including Brothers of The Same Mind, Chilly Uptown, and P-D2. “The narrative that there was only one person here is not accurate,” he says. “I want to make sure these artists are included in future TV shows and books about Seattle rap.”

There’s a worldwide trend afoot. In the past five years, more than a dozen albums from the Northwest’s early hip-hop years have been re-released across five labels, most of them in Europe. For the first time in decades, fans can obtain vinyl copies of storied early-era Seattle classics like Untranslated Prescriptions, Do The Math, Narcotik, Squeek Nutty Bug, and Jay Skee’s group Crooked Path. Back 2 Da Source in Belgium even reconstructed a “lost” Ghetto Chilldren album from demo tapes.

Novocaine132 is especially proud of his involvement with the release of “Beyond A Shadow of Doubt,” the first LP from Incredicrew. The duo of CMT and Supreme appeared in Mix-A-Lot’s “Posse on Broadway” video playing a rival crew. SPIN included the group on its hip-hop map.

In 1988, Incredicrew partnered with one of Seattle’s first female rappers, Chelly Chell, and her DJ Nerdy B. The foursome recorded a single, “He’s Incredible.” It was a local radio hit, and Incredicrew were hired to be Ever Rap’s in-house production team. Nerdy B and Chelly Chell joined them in the studio and they recorded ten songs of furious scratching and verses. When the album was finished, Ever Rap ran ads in music magazines announcing it coming soon. But suddenly Ever Rap’s distributor Enigma declared bankruptcy. Ever Rap was caught in the fray and forced to shut down. In the ensuing confusion, the completed quarter-inch master tapes of the Chelly Chell album were thought lost forever.

Novocaine132 found the tapes on a shelf where they’d been sitting for 30 years, literally covered in dust. The newly resurrected Ever Rap label released the lost album on vinyl in 2020, filling in a key missing piece of Seattle hip-hop history.

After the loss of their album, Nerdy B and Supreme kept in contact. Nerdy B changed his stage name to B-Max and joined Brothers of the Same Mind. Supreme started working with rapper Black Tek after Incredicrew broke up.

“Ex-Presidents was one of the best projects that ever came out of Seattle,” says Specs. The duo—Born Supreme and Black Tek—earn a shout-out on the Elevators tape, on the song, “The Brain.”

Like Elevators, there’s no music from Ex-Presidents on the Internet. When you Google them, there are zero results. The Flavor acknowledged the group multiple times, even asserting that their track “Sic Ill Shortie” ranks among Seattle’s greatest.

“I have their cassette,” says Specs. “Black Tek was the best rapper I knew at the time. He inspired a lot of Elevators shit. He always made me want to step up my bars, cuz he was a bars guy. Every bar is good.” E-Sharp worked on the Ex-Presidents project.

Specs credits Supreme and B-Max with the birth of Elevators. In 1992, he, E-Sharp, and a third member, Skrady Ray, were performing around town and refining their sound. Supreme and B-Max saw the group’s potential immediately and led them into the studio for the first time. “B-Max wanted to be the producer. He made our first beats. Supreme worked on those, too,” Specs continues. “We did two songs. It was a wavy sound, kind of like Native Tongues.”

“Me and E-Sharp would nerd out and philosophize,” he says. “We decided that we wanted it to be just me and him.” They wanted to make heavier hip-hop, based more on beats and scratching. “We wanted to be really artsy with it in a way that only me and him could do.”

The name “Elevators” sparked laughter among their peers. It’s a joke about elevator music. “It sounded hella funny to everybody, but we thought it was dope.” They recorded six songs, dubbed a bunch of cassettes, and started selling Elevators tapes on the street. “It was a good formula we had,” he adds. “I felt like it struck a chord for the time. When we came up with that first demo… People were like ‘Hell ya.’”

So why, right when all the attention and buzz was on them, did Elevators disappear? “E-Sharp got into the Islamic faith,” explains Specs. “He decided that making music was a sin. He gave me all his equipment and he quit.”

Specs was gutted. He tried to keep the group going by bringing back Skrady Ray. They played a couple of shows, but it wasn’t the same. For four years, Specs didn’t release any new music.

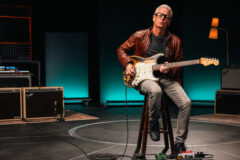

He found his way back into the limelight in 1997. Loosegroove, a label started by Pearl Jam guitarist Stone Gossard aimed to foster new Northwest talent. They planned to release a Seattle hip-hop compilation called 14 Fathoms Deep that would be distributed by Sony Music. They wanted Specs on it. He drew the album’s cover art, featuring graffiti letters surrounding a scuba diver grasping a microphone. Because he wasn’t in a group at the time, he hastily created one, enlisting help from his friend King Otto and former Top Notch bandmate FE3. The trio called themselves The Crew Clockwise. Their song, “A New Day,” is built around a backward looping piano line and is almost nine minutes long.

Afterward, he found new confidence and started releasing music again. “I put out fourteen self-released tapes between 1997 and 2001. That stuff is hard to find. They’re floating around somewhere. I don’t know who has them.” In 1999, he made a cameo on “Library Nation” by the Evil Tambourines, the first Seattle rap record from the Grunge label Sub Pop. In 2002, he released what he considers his first solo album, Numerology. It’s a homemade CD-R. He released it under the name ‘Specs One.’

The one and only song featuring Specs on Spotify is “So Clear.” It’s from Shadows, a 2017 album by Seattle rapper Wizdumb. “Numerology changed my life,” he says, reminiscing about the moment he found the CD at a local thrift store. It was the spark that set his own career alight. “Elevators taught me how to rap and Specs showed me that the rule book can be thrown out.”

“Specs is a rapper for rappers,” writes cultural writer Charles Mudede in the Stranger on the tenth anniversary of Specs’ second solo album. In his praise of 2003’s Return of The Artist, he says, Specs has “never followed a trend or a specific school. You can’t describe his beats and rhymes as Northwest, West Coast, or East Coast. His raps mostly refer to an almost pure and placeless hip-hop realm.”

Specs’ stature as a Northwest legend grows with each passing day. He shows no signs of slowing down. He continues to grind it out in the lab, making music and comics and paintings. He’s prolific and committed to the craft. His focus, as with Elevators, remains on producing tangible work. He recently dropped a cassette-only beat tape called “Yellow Bricks.” His latest project is a 7” lathe-cut vinyl. There are only 10 copies available.

To mark its 30th anniversary, Specs dusted off the original cassette and uploaded the storied Elevators tape to Bandcamp this year. “Why look at it as this thing that’s dead and gone?” he says. “A lot of my stuff was unsung. I’ve got to bring it back every once in a while to remind them.”

Last year, marking its 20th anniversary, he released Numerology on Bandcamp, too. “I’ve got shelves of tapes,” he says. “I’m holding on to everything I’ve made since I was 20. I’m sitting on a treasure trove.” He’s patient. “Since the world hasn’t called it important, people don’t think it’s important. But I think it’s important. The people that were involved in it definitely think it was important. Right now, we’re this unknown thing to the world. There’s no value placed upon it yet.”

Doesn’t he wish, after all this time, that Elevators had blown up, like Mix-A-Lot, and become a worldwide sensation?

“I’m not rich. But I do have my integrity score,” he says. “That’s 44 years of rapping how I want to rap. I’m way more into that than flying around in private jets or hanging out with rented models.” He continues, “Hip-hop is about making something out of nothing… Taking what you got in the attic or living room and making cool shit out of it. The art form is important to me.”

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.