If we’re talking fat, the visceral type is the real baddie. Though it makes up just 10 percent of body fat, it’s implicated in a number of health concerns, including diabetes and heart disease. Here’s everything you need to know about the adipose antagonist hiding deep inside.

What is visceral fat?

Fat comes in a few different “flavors”: white, brown, beige, and even pink. White fat cells are the most abundant and are important for energy storage – they tend to accumulate in the belly, thighs, and hips; brown are found mostly in infants, but also to a lesser extent in adults, to keep them warm; while beige and pink are types of white fat that can be converted when exposed to low temperatures or during pregnancy and lactation, respectively.

Fat can also be defined by its location, which is where visceral fat comes into the picture.

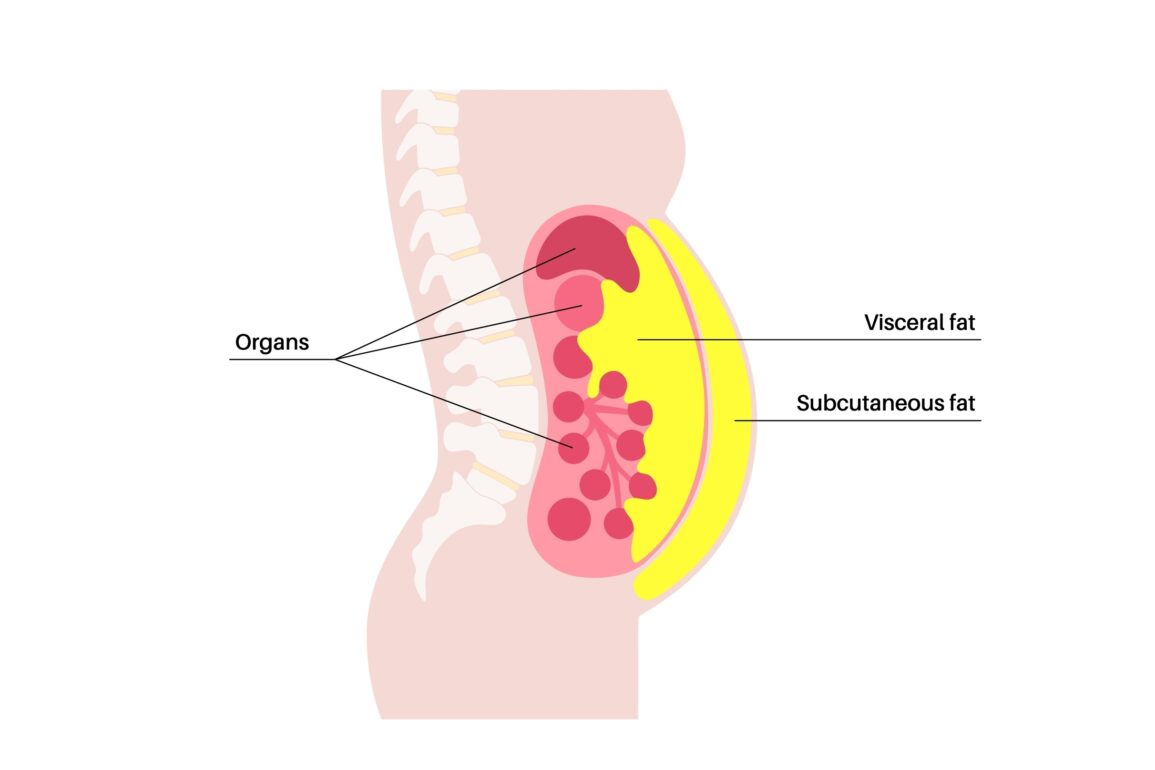

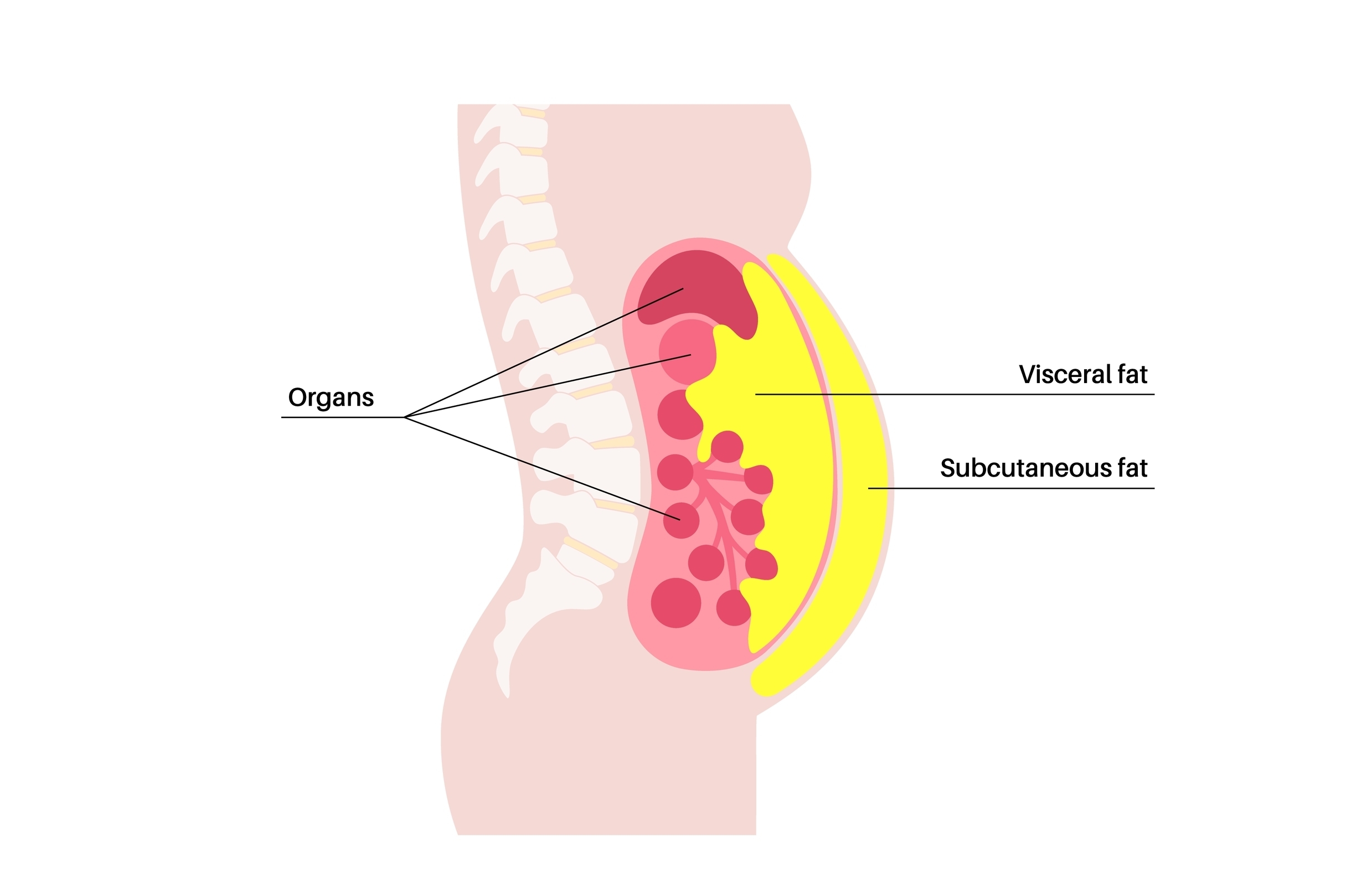

Sometimes referred to as “belly fat”, visceral fat, a type of white fat, lies deep within the abdominal cavity where it surrounds digestive organs such as the pancreas, intestines, and liver. It can also wrap itself around the heart. Some levels of visceral fat are necessary to protect our organs.

Visceral fat is found deep within your abdominal walls, surrounding your organs.

Image credit: Pikovit/Shutterstock.com

It is distinct from subcutaneous fat, which sits directly under the skin’s surface and that you can pinch between your fingers. Extreme amounts of subcutaneous fat can be a threat to our health, though not as much as visceral fat.

Why is it dangerous?

First of all, fat itself is not (necessarily) a villain. Having the right amount is vital to keep us warm, give us energy and essential fatty acids, help us to produce hormones, and absorb essential vitamins and minerals. It’s only when we have too much of it that fat can become a problem.

And visceral fat, in particular, poses a threat to our health. It has been linked with a higher risk of cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and certain cancers, among other things.

One of the main problems is that fat is biologically active: it secretes hormones and other molecules that can affect other tissues in the body, even those far away. Visceral fat, compared to subcutaneous fat, produces more such molecules, with potentially detrimental side effects for our health. For example, it releases more cytokines – proteins that are important in cell signaling – which are implicated in inflammation and associated with a number of chronic conditions.

Visceral fat is also thought to make proteins that constrict our blood vessels, which can cause blood pressure to rise.

Other medical conditions that have previously been linked to visceral fat include: dementia, asthma, breast cancer, and colorectal cancer.

Both genetic and environmental factors can influence a person’s levels of visceral fat: someone can be predisposed to store more of it, but their diet, lifestyle, and other factors such as stress levels also play an important part.

Symptoms of visceral fat, most notably a growing belly, are frustratingly similar to those of subcutaneous fat, so it is advised to seek a doctor’s advice if you have concerns.

How to get rid of it

Visceral fat can be difficult to target. People tend to lose weight pretty uniformly throughout the body so efforts to lose weight, while helpful, may not be enough. Instead, making a long-term commitment to eat a balanced diet and follow exercise guidelines is recommended to help reduce visceral fat.

It’s also worth considering other lifestyle changes, such as improving your sleep hygiene and attempting to reduce stress levels or alcohol intake – all of which are associated with visceral fat.

But, as always, you should talk any concerns over with your doctor and consult them before instigating any major changes.

The content of this article is not intended to be a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Always seek the advice of qualified health providers with questions you may have regarding medical conditions.

All “explainer” articles are confirmed by fact checkers to be correct at time of publishing. Text, images, and links may be edited, removed, or added to at a later date to keep information current.

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.