Hip-hop’s birth can be traced to a party in the recreation room of a Bronx, NY, high-rise apartment building. At 1520 Sedgwick Avenue, DJ Kool Herc, a Jamaican immigrant, curated hip-hop, music’s most reproduced—and disrespected—genre.

Over the decades, we’ve gotten to know all about New York-based hip-hop. Then we heard about what was going down on the West Coast. And then the South blew up, led by Atlanta, Miami, Memphis, and Houston artists.

When it comes to Chicago—particularly the South Side, the most talked-about and most maligned part of the city—our contributions in light of this year’s fiftieth anniversary of hip-hop are often skewed and, in some cases, ignored.

After all, out of hip-hop’s four main aspects—DJing, breakdancing, rhyming and graffiti—the genre’s other three take a backseat to rhyming.

But the hip-hop scene from Chicago’s South Side deserves its flowers. Some folks may not know this, but South Side heads have a few addresses and intersections of their own that live in the hearts and minds of those that know.

Who didn’t stop by Dr. Wax Records at 5225 S. Harper Avenue, Coop’s Underground, Track One Records in South Shore (my personal favorite), or the many other South Side stores that were the backdrop of so many tough decisions?

For example, Wu-Tang Clan’s Enter the Wu-Tang (36 Chambers) and A Tribe Called Quest’s Midnight Marauders—two bonafide classic albums—were released on the same day (November 9, 1993).

Even as a rabid fan of the Wu’s “Protect Ya Neck” and Tribe’s “Oh My God,” young Evan couldn’t buy both. And having vinyl, CD, or a tape before anyone in your friend group was a lofty social status.

Years later, at the tail-end of what I like to view as “Hip-Hop’s last Golden Age” (1993-1998), heads pondered a dilemma: which album to buy on September 29, 1998?

On that day, Tribe dropped The Love Movement, OutKast released Aquemini, Brand Nubian brought Foundation to the conversation, while Jay-Z released Vol. 2… Hard Knock Life, and Black Star, the duo of Mos Def (now Yasiin Bey) and Talib Kweli, dropped Mos Def & Talib Kweli Are Black Star, which features the track “Respiration” with the South Side’s own, Common.

How about college radio stations playing the artists and music that WGCI and B96 wouldn’t bother giving the time of day?

WHPK, located at 5706 S. University Avenue on the campus of the University of Chicago, and Kennedy-King College’s WKKC, formerly located at 6800 S. Wentworth Avenue and helmed by DJ PinkHouse, was the lifeline of young “Backpackers,” who were mostly influenced by boom bap hip-hop popularized by East Coast rappers.

The world is familiar with the intersection of 87th Street and Stony Island thanks to Avalon Park’s own Common, who spent decades shouting out the city through his music, acting career, and activism, and is widely recognized as Chicago’s hip-hop ambassador.

As a young kid who grew up in the South Side enclave of South Shore, Common’s second album, Resurrection continues to be a hyperlocal manifesto for me. Even though I loved Wu-Tang, Tribe, Mobb Deep, Public Enemy, Ice Cube, Boot Camp Clik, OutKast, et al., I personally identified with Common’s music because I actually lived the subject matter.

Going to parties with the crew and not sitting together in case something popped off, buying gear at stores in a Chicago neighborhood which is now called University Village (y’all remember the old name, I’m not saying it), and shouting out the high schools that had the finest girls, among other topics, were conversations I engaged in.

The venues where so many of us heard the music that became the soundtrack of our lives stand out in our memories—especially the ones thrown at 1900 S. Michigan Avenue. Who didn’t pull up to a function there?

And perhaps hip-hop’s greatest contribution to our global society is that the music and the culture bring people together. In Chicago, a city well-known for segregation, we met kids from other neighborhoods at these venues that we probably would not have interacted with otherwise.

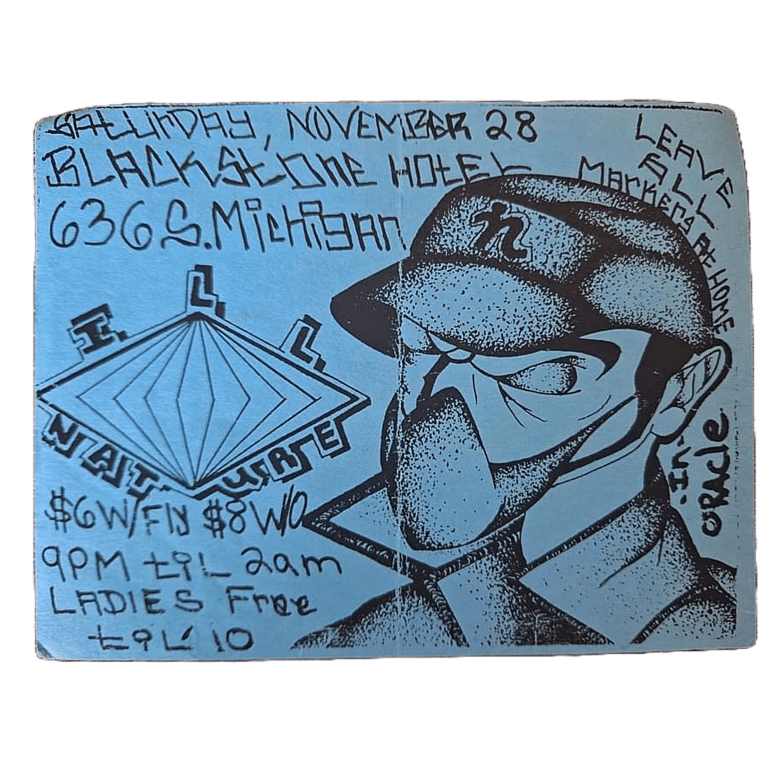

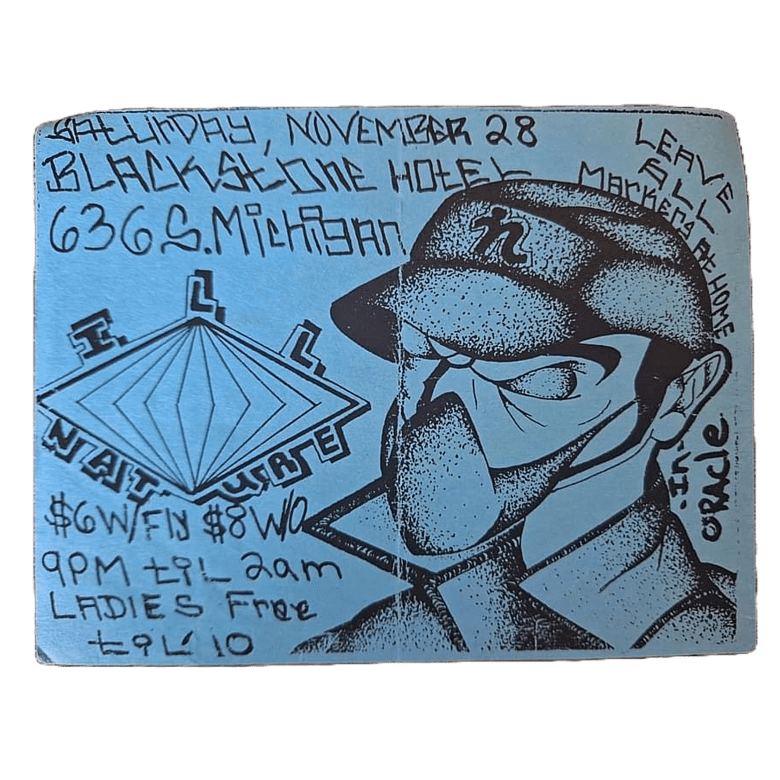

In November 1998, my crew, Ill Nature, threw a party at the historic Blackstone Hotel in downtown Chicago. Yes, me and the homies threw a party at a downtown hotel. A lot of people did.

But our function showed what the city could be if we all agreed to provide spaces for teens to make mistakes and learn from them. Fast-forward twenty-five years later, I doubt the adults in charge would allow teens to rent such a space. It seems like adults and teens don’t trust each other now more than ever—which isn’t new, but it feels like something is different these days.

The proof is in the pudding anytime we see a group of teens downtown. Unfortunately, they are lumped in with those who want to do harm. Very few of us want to differentiate.

Black South Siders most likely have Southern roots from folks who came to the city looking for a better life. Along the way, South Siders developed a “melting pot” for how musical tastes manifest over time. The range of stories and details from South Side born-and-bred artists have common threads.

From the Great Migration to the Chicago-based music TV series “Soul Train,” from the “Disco Demolition Derby” to the rise of House music, the ingredients of South Side hip-hop are baked within its history. Producers like Ye, The Legendary Traxster, No I.D., Prolyfic, SC, Young Chop, and so many others continue to spread the Chicago gospel via their beats.

But along the way, respect from the genre’s gatekeepers was fleeting. At one point in time, Chicago artists felt compelled to leave the city for New York or Los Angeles for opportunities.

In the 90s and early 2000s, Common and Ye, along many other South Side creatives, moved to position themselves for life-changing opportunities—to get famous.

Meanwhile, a recent crop of South Side-bred artists like South Shore’s G Herbo, along with Chief Keef, and Rooga, best known for his song, “GD Anthem,” had to relocate because it became unsafe due to the negative attention they received over time.

Unfortunately, some artists deal with family issues, local law enforcement blocking performances, rivals, and, perhaps the most vile form of negativity, “haters” who want to make a name for themselves.

Lil Durk told Vlad TV he moved from Chicago to Atlanta for “growth” reasons after law enforcement began to shut down his local shows.

In Rooga’s case, he relocated to California to get away from the aforementioned reasons. He points to West Coast rapper and businessman Nipsey Hussle’s murder as a cautionary tale. Hussle was murdered in the parking lot of the clothing store he owned in his neighborhood.

“You can’t stay in the city you damn near from. That’s where the hate comes from first, your own city. You gotta be a dummy to stay in your own city. It even happened to [Nipsey Hussle] in his own city,” Rooga told Vlad TV in a 2021 interview. “That’s the only way you’re going to secure the bag and secure your family and secure yourself.”

Of course, not everyone left. Chance the Rapper’s music is heavily influenced by gospel and House, two Chicago imports. Also, it appears he didn’t need to dwell over a tough decision to leave the city like rappers from previous generations did.

Chance packing in crowds at his recent United Center performance celebrating the tenth anniversary of his seminal mixtape, Acid Rap, shows that Chicago rap artists can blow up while maintaining a local presence.

Influential artists like Pac Man, whom some folks recognize as the innovator of drill music, and Chief Keef are names who stand out. Your favorite drill artists, whether in the states or overseas, probably view Keef as a legend but have no idea who Pac Man is.

Pac Man, who died in 2010, released the track “It’s a Drill” shortly before the world discovered Drill music (and around the same time when Chicago became a pejorative for right-wing talking points). Sometimes, especially with Black creatives, the inventor is cast aside in favor of the much more popular artist.

As I explained in a 2021 series of social media posts regarding adults providing teens with safe spaces, some of us felt ostracized by the city’s gang culture, larger and more well-known cliques and crews, and the House music scene.

We didn’t feel the love, so we created our own communities. Along the way, as we were creating spaces for ourselves, we—of course not everyone—may have engaged in soft forms of homophobia and misogyny (and misogynoir, a brand of misogyny that specifically targets Black women) within hip-hop’s extremely competitive culture.

Englewood-raised emcee Psalm One says as much in her article “Ain’t No Human Resources in Hip-Hop,” regarding the ostracism she received during her time at Rhymesayers Entertainment, and in her book, Her Word Is Bond, where she describes the systemic issues within the culture: “She’s allowed in the boys’ club temporarily, with a chaperone, but she’s alone, she’s prey.”

Chicago has been left “outside” when it comes to our contributions to hip-hop.

As much as folks love to focus on the negative, so much great music is being exposed to the masses. Also, many South Side artists are utilizing their platforms to let people know about the social justice issues they care about most.

Whether it’s through politics and nonprofit work (Rhymefest), expanding Black folks’s blueprint in the ever-growing cannabis industry (Vic Mensa and Mick Jenkins), fusing activism and mental health awareness (Nikki Lynette), to hosting block parties in their own neighborhoods (Noname), South Side artists are more than just their music.

The city’s hip-hop scene has a lot to say and many more places to go. Tell your stories because, otherwise, someone will tell them for you.

Evan F. Moore is an award-winning writer, author, and DePaul University journalism adjunct instructor. Evan is a third-generation South Shore homeowner.

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.