In October of ’88, the venerable Ultramagnetic MC’s advanced first-generation hip hop with their landmark debut, Critical Beatdown, a singular new-school rap classic that swapped the era’s popular blueprint of simple rhyme schemes and common deliveries for deft, dense flows and off-kilter lyrics. The early Bronx-banger LP (which was oh-so-close to featuring KRS-One as a group member), is a key marker of the genre’s second chapter, an era that found Slick Rick, De La Soul, and Rakim also cracking the block-party rap mold.

Ultramagnetic are also widely credited as the first hip hop group to use a sampler as an instrument, rather than just a simple rhythm tool. Founding member Cedric ‘Ced Gee’ Miller’s twists and flips of heavy funk samples using the legendary E-mu SP-1200 proved well ahead of their time, and have become popular sample sources themselves. Over Ced’s next-wave production, lead-Ultra MC Keith Thornton, aka Kool Keith, set the bar for rap quirk and eccentrics, before proceeding to raise it to galactic heights as a solo artist.

Seven Ultramagnetic albums followed Critical Beatdown, with an eighth, Ultramagnetic MCs: Kool Keith x Ced Gee set to be released in 2024 on Ruffnation Records. In celebration of hip hop turning 50 this year, Keith and Ced joined SPIN to discuss their memories of rap’s early days and the role they played in expanding the art of recorded rhyme.

SPIN: Let’s set the scene. It’s 1988 and many crews and MC’s are still on the entire “Yes, yes ya’ll … to the beat y’all” vibe, all the back-and-forth routines, the call-and-responses with the crowd. Listening to Critical Beatdown it seems you were intent on moving past that rap approach. What other acts inspired you to go there, and what role do you feel you played in the genre’s overall shift?

Kool Keith: We actually listened to all the styles, but when we was coming around rap was already changing, the vocals were changing anyway…MC Shan, Rakim and the Treacherous Three were really the first to ever change the vocals, you know what I’m saying? They brought a real diversity with the vocals themselves. But then what we changed ourselves, it was more of a lyric change.

Ced Gee: For getting rap out of that whole ‘Yes, yes y’all’ mode, I really think you have to give that credit to the Cold Crush. Live, most MCs had their certain rhymes, so they’d say their rhymes, and once those were done, for the rest of the night it was just shouting people out. You know, all the “Yes, yes, y’all … Billy Bill’s in the house … Joe Schmoe’s in the house …,” all that stuff.

But see, Cold Crush came with so many routines and different rhymes, that began to change things. Then you listen to, like, JDL and Grandmaster Caz, they added to that by bringing their own flows too. And then what the Treacherous Three did, they were the first who elevated on that and started using a greater vocabulary. I think all those groups influenced our new mode.

Ultramagnetic MC’s was a pretty futuristic name at that point, compared to the other artists on the early rap scene, many of whom were using real basic, even goofy names. Ultramagnetic even feels kind of sci-fi. Was that name meant to match the forward-thinking approach of your music?

Keith: Actually, I didn’t mean to name our group such a high tech name, we just had to find a name quickly, because we had to put out a record so fast to match “Ego Trippin”—it wasn’t any specific idea, I just randomly named it because the records was getting pressed up and we were already using big words, so I said, you know what, let’s just use this here big-ass word: Ultra-mag-net-ic.

You two first met in high school, then founded Ultramagnetic MC’s in 1984 with a few others, including Moe Love and TR Love. That was a really formative moment for hip hop, 1984, and the Bronx was a serious hotbed for the culture—what are your first memories of rap in those early Bronx days?

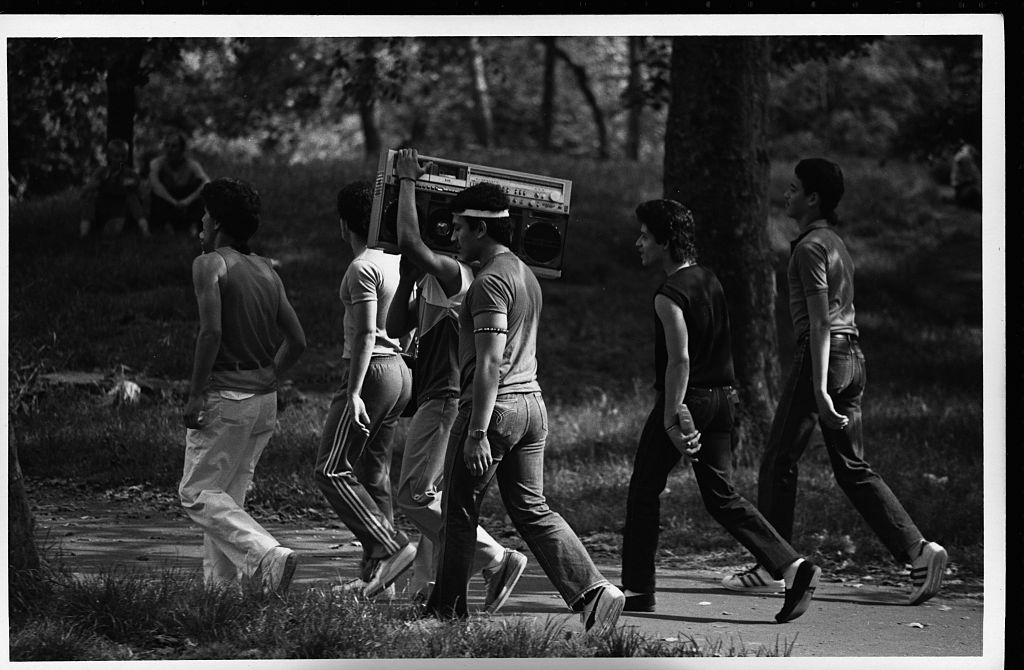

Keith: When rap was starting, I was still in junior high, and I just remember people walking around with those big boxes in New York…everybody had to have a big radio to carry around—four guys to a radio, that’s what it was. You know, they had the Sonys, the JVCs, the Nippons, the Panasonics. It was a huge thing in New York City, and I don’t think no other city had that at the time. I mean, everybody had a big box, everybody. That’s still my first vision of rap.

Ced: In the seventh grade, they had this so-called “African American Week”, this little program in the auditorium at school. They had the African stories and girls doing the African dance and all that, then out of nowhere—B-boy DJ Clark Kent suddenly comes out with this Superman costume on, but also with glasses on … so he was like, Clark Kent and Superman at the same time! I remember seeing that, then him going into his DJ routine, and it just changed my life. That was it … rap, I had to do it.

Rap began in Bronx parties and open park jams, then it spread to small nightclubs, but it took a good minute before it spread all over New York. Being that you both lived in the borough it was born, you were exposed to rap earlier than most New Yorkers—can you recall the first live rap show you went to, who you saw and where that would have been?

Keith: Definitely, I know I went to the T-Connection [club] and I saw the Cold Crush Brothers perform there. Right off of Gun Hill Road, 225th on the 2 train [Bronx stop on NYC Subway]. That was the spot right there.

Ced: It was in my old neighborhood in the West Bronx. Our local DJ, DJ Chuck-a-luck, he was trying to do what Herc did, playing outside in the neighborhood, and me and my friends used to watch from the window. Then in ’82, while our parents were sleeping, we’d move to the fire escape … then we started climbing down … then we elevated that to sneaking around the corner to watch him.

By the time rap was all over the place in New York, it was starting to be produced and sold. In the beginning you had to witness it in person or have a mixtape of a DJ’s set—suddenly you could now have it at home. What was the first rap single or album you ever owned, the one that really put you on and locked you in?

Keith: I’m pretty sure it was Funky Four Plus One’s “It’s the Joint.” That was my first joint.

Ced: As an artist, the real important albums weren’t really rap, it was the ones that introduced me to music, period. In 4th grade I saved up my allowance and bought two records, Billy Paul “Me and Mrs. Jones” and The Four Tops “Ain’t no Woman Like the One I Got.”

So as rap started selling big, studios are taking in more and more groups, which also means some serious trash records were getting made. What were the worst early rap records you ever heard? Was there anything that just you had you like, “Who the hell ok’d this record?!”

Keith: I think ‘Rappin Duke’, would definitely have to be ‘Rappin Duke’ [the imitation John Wayne rap].

Ced: I’m gonna go with Newcleus’ ”Jam on It”. It was like they was mocking rap to me… everything was so overdone, the whole ‘Jammm ahwn-it, Jammm ahwn-it!’ It wasn’t a real crew, it was like, where did these clowns come from? Why do they have a mic?

In those formative days it was all about crews. MCs doing routines togethers, back-and-forths. DJs were always a huge part of that. It was never just a rapper doing their own full songs. Who would you say is your favorite rap crew, back from when crews were the norm?

Ced: When I started out, I used to follow Grand Wizard Theodore and the L Brothers [Mean Gene & Grandwizard Theodore]. Theodore fascinated me, because he’s the one who brought out the scratch. I would follow them everywhere. And then eventually, after changing and changing and changing lineups, they became The Fantastic Romantic 5.

Theodore brought out the scratching and the drop-needle cuts, you know, then Grandmaster Flash ran with that and intrigued people with his speed and timing. Flash used to cut on time like a sampling machine, you know? That’s how precise Flash was.

Keith: I actually didn’t really have a favorite rap crew, I just had a lot of funk groups I liked. In fact, I only bought one rap record back then. I really bought a lot of funk records when I was making songs, I got a lot of Con Funk Shun, Slave, Dazz Band. A lot of Earth Wind & Fire, Brass Construction.

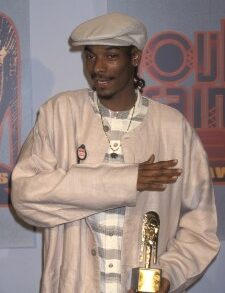

Fashion has always been a huge part of hip hop. Some artists, still, see fashion as right up there with rhyme skills when it comes to being an elite MC. You’ve witnessed a lot of hip hop fashion trends come and go, what would your all-time favorite and least favorite trends be?

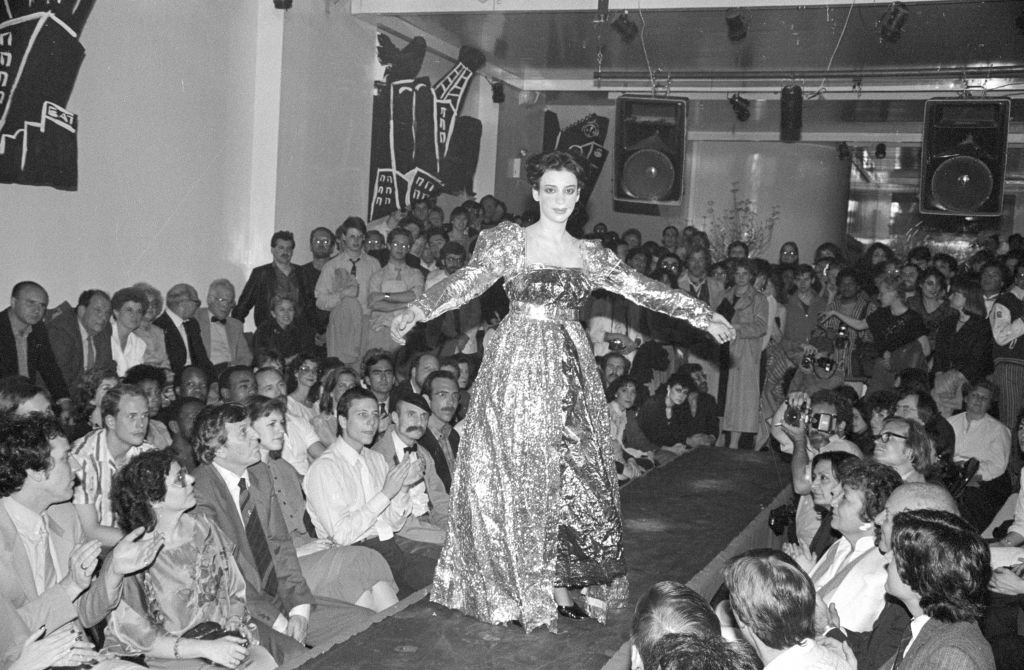

Keith: Man, my all-time favorite was the sharkskin pants, for sure. And I liked the turtlenecks, the mock necks with the British Walkers, the Cortefiel coat. Those were from all different eras. But I didn’t like the aluminum foil era or whatever that was. When all the girls were wearing the aluminum foil dresses.

Ced: You mean the ‘shiny suit era’? That’s what popped off when Puffy had them wearing the shiny suits in the videos. You can blame Bad Boy for that one.

Keith: Right, that’s it! The shiny suits, and after that the girls started wearing those dresses with the aluminum foil lining too.

Ced: As far as what I liked, when they had the AJs, or the ‘stitch-joints’ they used to call them, and the British Walkers—then you’d rock your silver medallion with those. Of course, the Mach Five glasses, the big gold frames. Then before the British Walker, you had the Playboy shoe. The ‘Hustler Shoe’. I could go on and on.

What I didn’t like though is when the rappers started rocking the tight pants and the high boots. Because that was no longer real hip hop. And the rappers knew it. Most were just being told by their labels they had to expand their audiences, so they were out there trying to be punk rock-ish.

You’ve both witnessed a real transformation of rap music over the years and it’s probably taken some turns you never would have imagined. Considering where rap is now versus where it all started, how do you feel about where we’re at? Does it feel like rap is off-track?

Ced: It’s not everyone, but so many MC’s today just get lazy. For example, like when me and Keith would be writing a rhyme, we would often get to a point where we might be like, ‘Aw man, what can I say here?’…but we never gave up. And today, it feels like what has become acceptable is, to think ‘If I get stuck, fuck it, I’ll just mumble over it!’ They’re not trying to find the words, they just mumble to get to the next line.

And knowing they [mumble rappers] can still get paid to do that, that’s why they keep that up. They’re just thinking, ‘I don’t really have to get to the studio and write anything, I could just go in and mumble things’—which, yes, is a form of ad-libbing, like when James Brown would do his ‘Awh! Good God!’—but c’mon, some MC’s are doing for that the whole record. At least James Brown gave you six or seven different lines.

Gentlemen, thanks for all the knowledge! To wrap things up, are there any musicians or bands that we would never guess that you’re into? And what would your all-time dream collaboration outside of the rap world be?

Ced: I’m really into Neil Sedaka. Frankie Valli and the Four Seasons. Lou Rawls. And for collab, of course it’d be James Brown. He was such a precision person. Anyone who samples records knows, it was easy to loop a James Brown record because the timing was impeccable. Him and his band were like a computer, which as a producer, I’m just amazed by.

Keith: For me, I really like the Talking Heads, always have. And my dream collab? I think that’d have to be maybe me and Quincy. Yeah, Quincy Jones.

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.