This is an edition of the newsletter Show Notes, in which Samuel Hine reports from the front row of the spring and fall fashion weeks. Sign up here to get it in your inbox.

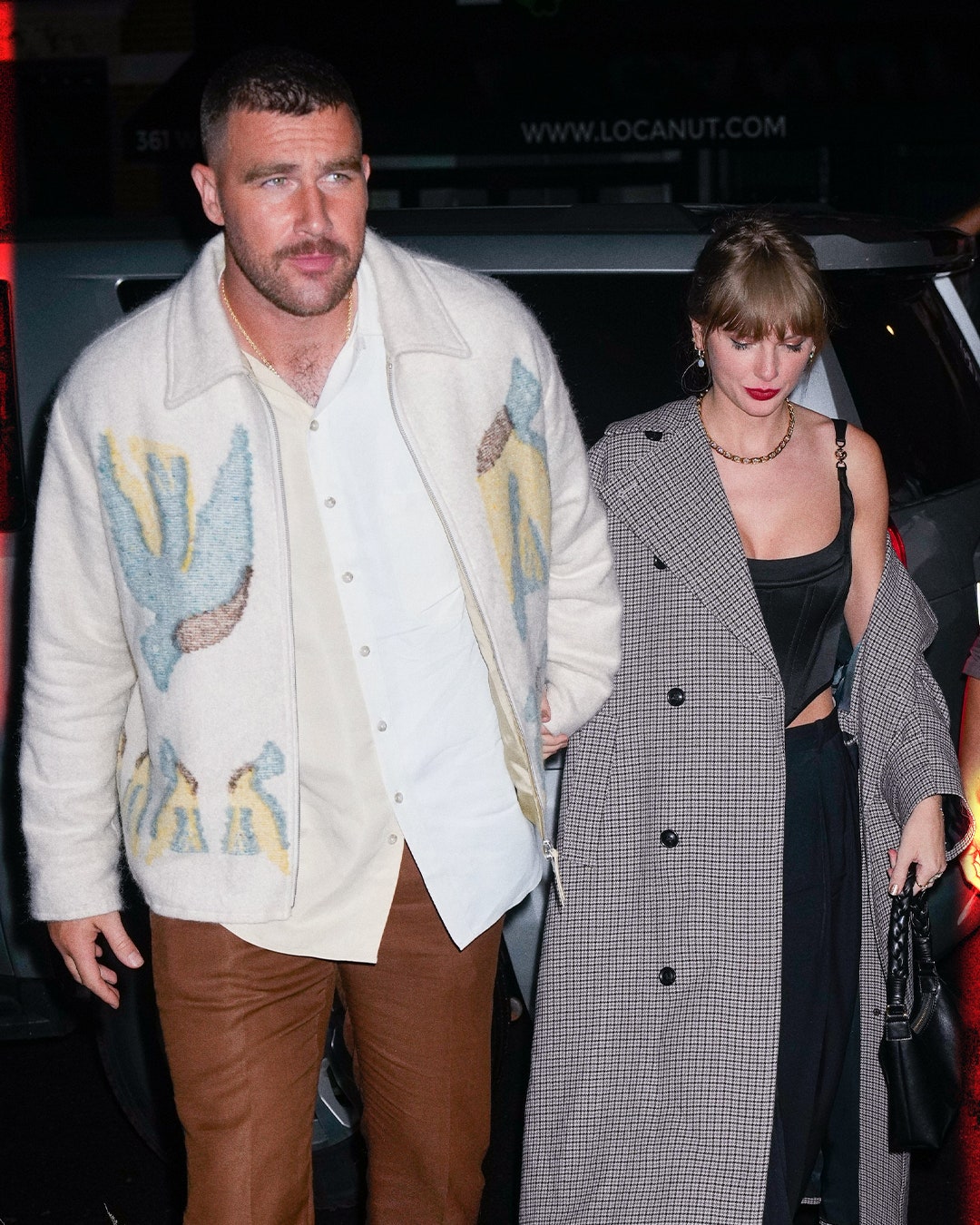

Last week, it seemed like every fashion reporter was calling around asking the same question: who is Travis Kelce’s stylist? Thanks to his rather, uh, high profile rumored relationship, America was getting an extra close look at Kelce. And at his date night (and pre-game) outfits. Naturally, we wanted to know who was helping the Chiefs tight end craft his image at such a critical moment.

But as I soon learned, and as my buddy Jacob Gallagher at the Wall Street Journal reported, the Chiefs tight end is in fact his own stylist. He uses red carpet pros like Sasha Elina and Anastasia Walker for special appearances, but on an average day, he puts his pants on just like the rest of us: one leg at a time, all by himself. “I kind of just do it off of instinct,” he told the WSJ about his pre-game wardrobing process, which tends to take place in his walk-in closet rather than a studio filled with assistants toting handheld steamers.

I found this revelation interesting for a couple reasons. The first is the fact that, as my colleague Eileen Cartter noted, by going out with Taylor Swift, Kelce is currently in his own personal menswear Super Bowl. Everything he does, and everything he wears, is being relentlessly analyzed by the public. Even the most avowed clothes horse, as Kelce is, would be forgiven for calling in a big gun like Karla Welch—the Andy Reid of Hollywood stylists, a visionary play caller—to lend a hand.

More surprising is that Kelce looks like he has a stylist.

This is not a knock on the two-time Super Bowl winner. His ensembles are clearly put together with a great amount of care—per Gallagher, it can take him over 3 hours to get dressed before heading to Arrowhead Stadium. It shows. Kelce’s outfits appear to be assembled with the care of a fashion professional. For one, his clothing fits him just right, no easy feat when you weigh in at 6’5” and 250 lbs.

What truly characterizes his outfits, though, is their distinct cohesion, as if every piece was purchased together. He wears full looks, each garments’ silhouette and vibe in accordance with the rest, as when he wore pink Amiri trousers with white boots and a camp shirt made out of vintage Chanel scarves. Each fit, tensionless and match-y, appears to be designed to serve a purpose. As if put together by a third-party with a personal shopper and tailor on speed dial. Don’t take my word for it: X has been aflame with praise for Kelce’s non-existent stylist.

Look around and you’ll notice that Kelce is not alone. Lots of men, from celebs to civilians, look like they have personal stylists these days. From the locker rooms of the NFL to the streets of New York, dudes are walking around like they’re a few weeks into an HBO press tour.

This seasonless and bicoastal frequency is squarely in the mushy middle between casual and formal, relaxed enough to signal that you’re off-duty, but fancy enough to get a good table at your local upscale sushi spot, with or without a pop star by your side. Call it Nobu style. Its adherents emulate many of the moves that stylists often bring to high-profile jobs. Matching sets are peak Nobu style. Assemblages of the “right” brands—Kelce rocks critically adored labels like Marni, Fear Of God, and Jil Sander, as well as niche names like KidSuper—is Nobu style, too. A suit and tie? Nope. A designer suit with a T-shirt and sneakers? Right this way, sir.

The designer Emily Dawn Long has clocked the aesthetic all over Instagram and hotspot neighborhoods like Dimes Square. “More guys are doing the full fit thing,” she says. “Instead of wearing one great jacket and building their look around that, they’ll have a really good jacket, really good pants, a cool hat, cool shoes.” Walk by Le Dive on a nice day and you’ll indeed notice a striking freshness in the crowd—everybody’s clothes look as brand new as the Jil Sander zip-up Kelce wore on a night out with Swift last weekend.

Long, who has a background in personal styling, cites the sheer rapidity of the menswear trend cycle as fuel for Nobu style. “Everyone’s trying to make the next viral look, and everyone is referencing someone else” these days, she says.

It’s no wonder, she adds, that regular guys are stepping out looking like Lewis Hamilton, the undisputed king of flexy sets, a uniform that reliably looks great in flashbulb photos and means whatever you want it to. (Hamilton works with the stylist Eric McNeal.) Thanks to the competitive influence of social media, we’re living in a sort of fashion ouroboros, where everybody is biting everybody else’s look. “The celebrities are dressing like regular people, regular people are looking at what influencers are wearing, and influencers are trying to dress like celebrities,” Long says. Which is probably how Joe Jonas ended up wearing double-knees and crochet hats by Long’s namesake brand—both staples of “regular” downtown street style. Nobu style aspires to authenticity, but it is, in a sense, costume.

The rise of the men’s fashion weeks as major cultural events has also undoubtedly contributed to the rise of Nobu style. It wasn’t so long ago that fashion weeks were mostly the domain of buyers and editors, who would pick apart what they saw on the runways to create their own original narratives in magazine spreads and department store floors. Now, social media is flooded with viral runway looks, and VIP influencers and ambassadors, branded head-to-toe in the front row, are considered paragons of fashion. Nobu style, downstream from these global luxury brands, is placeless—Kelce, in his Louis Vuitton denim kit, would look at home in Paris or Kansas City.

The shopping experience today can push guys to wear things that feel over-stylized, too. If the best men’s fashion boutiques used to reflect the specific and occasionally strange tastes of their owners and buyers, whose selections made an argument for what was cool right now, and also where menswear was headed, now the best stores—Departamento in Los Angeles and the Dover Street Market empire come to mind—buy large swathes of runway looks. It’s special to be able to try on gear you’ve screenshotted on Vogue Runway. But take it a step too far, and you might look like an SSENSE model, whose wild head-to-toe merchandising has become a fashion meme for our time. Nobu style is not understated. It’s all about every piece on your body being branded and major, like you’re stunting in an NBA tunnel. It’s about popping with color and pattern, as if you’re hosting SNL. It’s about every millimeter of fabric being tailored to perfection, lest you be caught slipping by Backgrid.

Some observers argue that these guys would be better off if they actually did have stylists. Cultural critic Raven Smith characterizes Nobu style as “shop-bought not home-grown” and “paint-by-numbers rather than feel-it-out.” There’s certainly a safety in it, which can feel crucial in our era of public scrutiny. But this, Smith says, seems to miss the point of getting dressed in expressive clothing in the first place, and ignores the creative possibilities of collaboration. “References that marginally tweak tradition are so accessible that it’s become easy to consult nobody and dress with a palatable feeling of flair, without any genuine personal commentary,” he says.

Then again, Nobu style might represent a watershed moment in American masculinity. It’s significant that a famous corn-fed tight end who lives in Missouri considers shopping for fancy clothes to be one of his favorite hobbies. If that’s a new status quo, it’s a meaningful one. And it’s clearly catching on throughout the NFL, which was long resistant to the more flamboyant fashion choices seen in Hollywood and the NBA. According to Detroit Lions defensive end Romeo Okwara, one of the most original and soulful dressers in all of sports, the locker room at Ford Field is often filled with chatter about planned shopping trips to Japan. “Guys feel like they have a little more freedom to be themselves,” says Okwara, who adds that when he played for the Giants a few years back, all-team meetings on the eve of games became the scene of competitive fit battles. “It was just guys shopping and buying stuff they fucked with,” he says. Which is important, whether the results are paint-by-numbers or not.

What does this all portend for actual stylists? The “no stylist” movement has been strong in hip-hop for years, and the likes of Timothée Chalamet, the king of chaotic daywear, have proved that Nobu style is by no means a requisite for fame. (And in fact we spill more ink over the most unpredictable dressers—looking at you, Adam Sandler—than those who hit every note.) But the role of the modern celeb stylist is broader than making moodboards. Well-connected stylists are critical for celebrities who want to land lucrative brand deals and get invited to fashion shows and industry tentpoles like the Met Gala. And as I’ve previously reported, as red carpet events have grown in frequency and scale, stylists have, if anything, become overburdened. Their influence is in no danger of waning, and in fact the rise of Nobu style is an affirmation that the work they do is resonating.

Nobu style, on the other hand, strikes me as a mere stop on a long journey of discovery, an expression of genuine enthusiasm that can lead to a more personal relationship with clothing. It’s anyone’s guess how Kelce’s passion for his walk-in closet will develop. His rumored girlfriend, Swift, has a stylist but famously looks unstyled. It will be fascinating to see how they influence each other. But for now, Kelce appears to be steadfastly following his own sartorial instincts. As he put it to the WSJ, he already considers his gametime outfits to be bigger than himself. “For the most part,” he says, “I do it to put a smile on somebody’s face.”

See all of our newsletters, including Show Notes, here.

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.