A U.S. government agency is looking to block an $8.5 billion transaction between Coach-owner Tapestry Inc. and Versace and Michael Kors’ parent company Capri Holdings. The Federal Trade Commission (“FTC”) filed suit against Tapestry and Capri this spring, roughly eight months after the two U.S. fashion groups announced that they had reached a deal to merge their respective holdings and create what has been likened to the American equivalent of European luxury goods groups like LVMH, Kering, and Richemont.

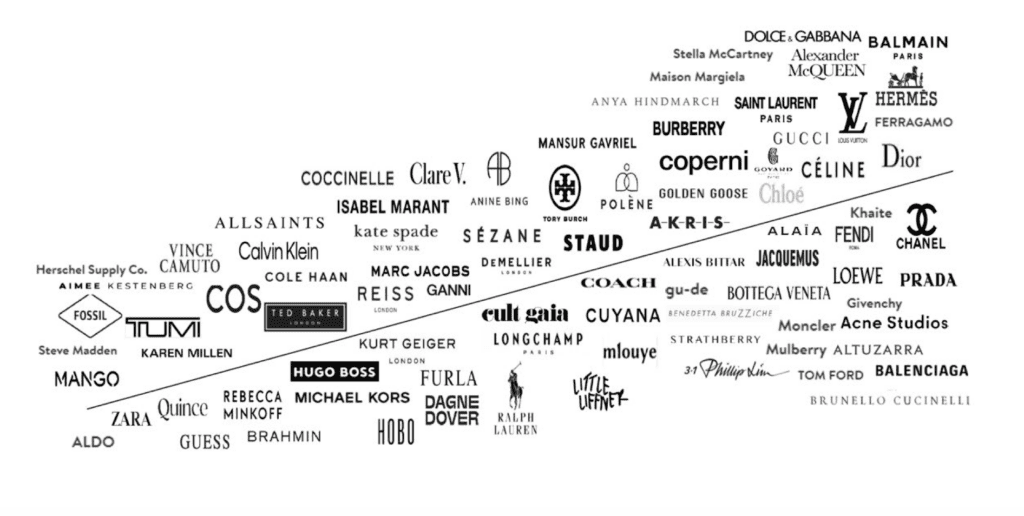

In the somewhat heavily-redacted administrative complaint that it filed on April 23, the FTC argues that the Tapestry, Capri deal, if permitted, “would eliminate fierce head-to-head competition on many important attributes including price, discounting, and design,” resulting in “tens of millions of Americans that purchase Coach, Kade Spade, and Michael Kors products fac[ing] higher prices.” In other words, if Tapestry – which owns Coach, Kate Spade, and Stuart Weitzman – acquires Capri, whose brands include Versace, Jimmy Choo, and Michael Kors, “Tapestry would gain a dominant market share in the ‘accessible luxury’ handbag market, dwarfing every other competitor” to the detriment of American shoppers.

Faced with the FTC-initiated litigation, Tapestry and Capri have argued in subsequent filings of their own that the proposed merger transaction “poses no risk of anticompetitive harm to any consumer of handbags” in large part because there is still a “myriad [of] brands offering handbags across a wide and essentially contiguous spectrum of pricing.”

“New brands and dynamic competitors are leveraging the COVID-accelerated shift to online sales, marketing, and product placement to rapidly build brand value, tap into consumer sentiment, and aggressively win sales,” Capri contends. “Meanwhile, longstanding brands like Burberry, Cole Haan, Gucci, Longchamp, Louis Vuitton, Marc Jacobs, Ralph Lauren, Tory Burch, Tumi, and others continue to compete aggressively to stay relevant in this evolving industry.” Not limited to those brands, Capri and Tapestry claim that they compete with “far more than 150 handbag brands, across prices and categories,” and thus, their proposed transaction “poses no risk of anticompetitive harm to any consumer of handbags.”

Does the FTC Have a Case?

As for whether the FTC can successfully stand in the way of the proposed Tapestry, Capri deal, that will “primarily depend on how it defines of the relevant market and then what the [Herfindahl-Hirschman Index] is” for the market, Brian Quinn, a professor at Boston College Law School, who focuses on corporate law and transaction structuring, told TFL. The Herfindahl-Hirschman Index – or “HHI” – measures the market concentration of the 50 largest companies in a particular industry to determine whether there is “sufficient competition among industry participants to avoid price-setting and other anticompetitive behaviors.”

While it appears that the FTC is looking to narrowly construe the market at issue as the “accessible luxury” handbag market, how exactly it defines the scope of that market is not immediately clear, according to Tapestry and Capri.

In its complaint, the FTC sheds some light on how it views the market, stating that “accessible luxury” brands’ products occupy a price range that is “separate and distinct from mass-market offerings, which typically fall under $100, and true luxury handbags.” At the same time, it contends that the market for “accessible luxury” handbags also “has distinct customers: middle- and lower-income consumers who seek out high-quality items at affordable prices.” Still yet, the FTC has asserted that “accessible luxury” handbags also have “peculiar characteristics” – namely, quality, discounting and promotions, production, and omnichannel approach and sales experiences – that “distinguish them from those offered by mass-market brands and by the European true luxury fashion houses.” (Part of the issue here, per Tapestry and Capri, is that the FTC does not provide a complete definition of the market, as it fails to define what constitutes a “handbag,” for example.)

Counsel for Tapestry and Capri urged a U.S. District Court for the Southern District of New York judge to require the FTC to provide a more exact definition of the relevant market, arguing that its as-of-now “unintelligible market definition and theory of consumer harm make no sense in this industry.” However, the court rejected their motion, with SDNY Judge Jennifer Rochon deciding earlier this month that the FTC’s complaint is “not so unintelligible or unclear that defendants lack sufficient notice of the allegations made against them” and thus, a more definitive statement of the market will come in connection with the parties’ discovery.

Regardless of how the FTC defines the market, Tapestry and Capri argue that the regulator will fall short in making its anti-competition case against them, “as economic analysis will show at trial [that] in any properly defined market, Coach, Kate Spade, and Michael Kors would represent less than 30 percent of sales, which does not give rise to any presumption of likely harm in this highly dynamic and differentiated industry.” Looking at the Michael Kors brand, for instance, Capri asserts that “the combined trends of declining sales [for the brand] and the increasing sales and shares of competing products … demonstrate that the merged entity will not have power to harm consumers.”

Continuing on, Capri argues that not only has “Michael Kors lost significant market share in handbags over the past five years, but Coach and Kate Spade did,” as well. The brands that primarily gained market share as a result – namely, “Louis Vuitton, Gucci, and Saint Laurent, [which are] all owned by massive European conglomerates with handbag sales, revenues, and market caps at many multiples of the parties” – have done so by “connecting with consumers and offering so-called ‘aspirational luxury’ products.” And at the same time, counsel for Capri claims that FTC “completely ignores that the handbag industry is known for significant ease of entry” and that new brands that “have emerged only in the past 10 years … have nonetheless achieved significant brand awareness and popularity with consumers and increased their presence across various channels,” thereby, creating additional sources of competition.

In short: Proving “undue concentration” in the relevant market is part of the FTC’s prima facie case, and the regulator will fail given that “in any properly defined market, the combined share of Tapestry’s and Capri’s handbag brands is not large enough to show any likelihood of harm to consumers … in this highly dynamic and differentiated industry,” the defendants argue.

The case is Federal Trade Commission v. Tapestry, Inc., 1:24-cv-03109 (SDNY).

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.