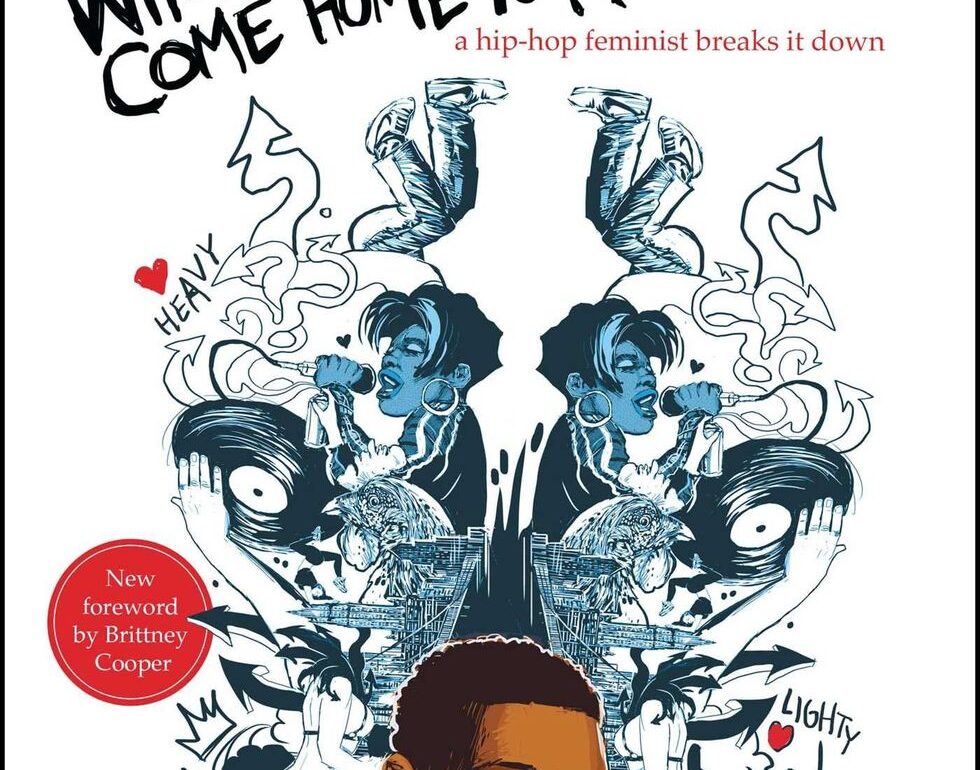

It took just over 25 years after hip-hop’s inception for a woman author to engage the culture with feminist thought. In 1999, journalist and author Joan Morgan published When Chickenheads Come Home to Roost: A Hip-Hop Feminist Breaks It Down, once deemed curio within music literature. Unless they were music journalists or orators, women were rarely given authority to critique and detail their connection to hip-hop in longform; men largely postured themselves as experts on the genre and its roots. As hip-hop reaches its 50th anniversary, the reach of women hip-hop authors stands firm against the patriarchal ideologies that have tried to silence their stories, from fictional to autobiographical.

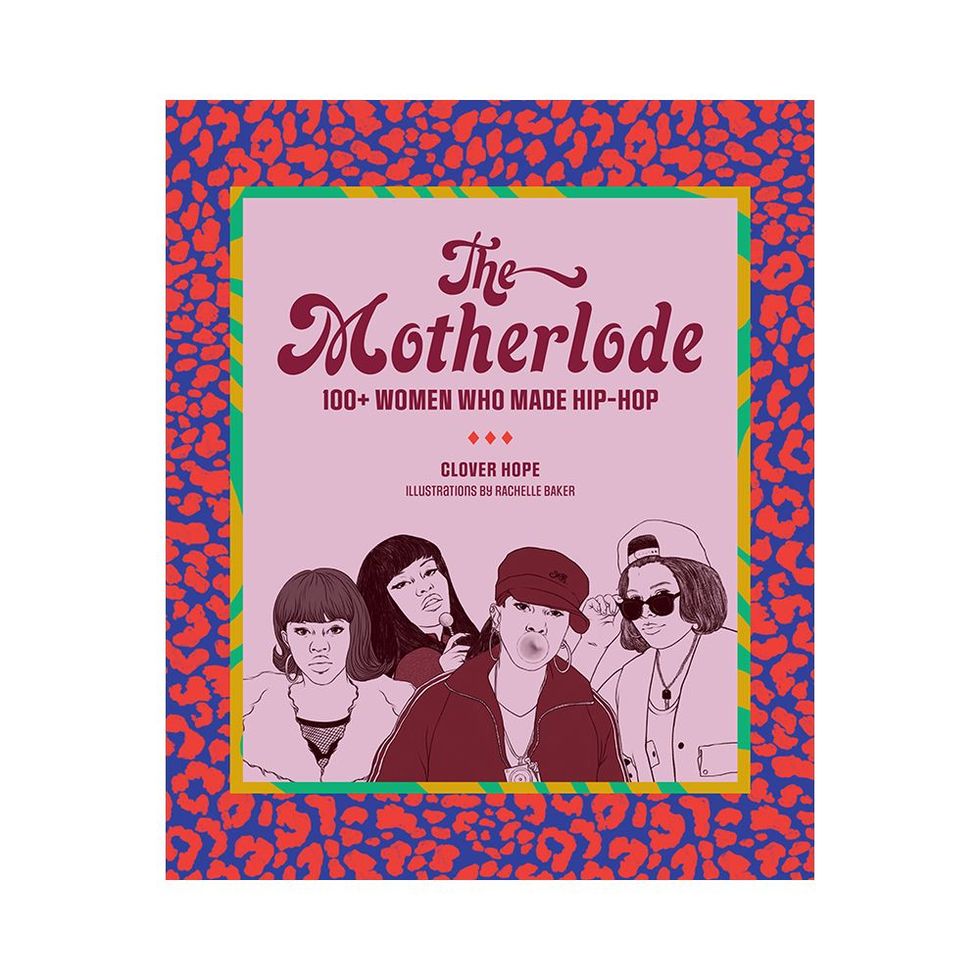

“I think that if you’re a hip-hop fan, especially a ‘rap nerd,’ you’re used to doing a ton of research and finding CDs of artists you don’t know, or really digging in the crates,” says Clover Hope, author of The Motherlode, which spotlights over 100 women who shaped rap music. “Part of that process as a hip-hop fan, I’ve discovered artists of whatever gender outside of what I was used to, and I’m not sure that men have that same practice. That’s what I’ve noticed, it was kind of a blind spot for them.”

“There aren’t very many books by women about hip-hop aside from the more recent works, and of course, there’s some seminal works in the past, as well,” says Kiana Fitzgerald, author of Ode to Hip-Hop. “But I think there have been many books about hip-hop that have a male perspective, especially white men. I feel like white men kind of have a monopoly on hip-hop [writing] right now as they have since the very beginning, unfortunately.”

Despite the sexist and misogynistic standards that have positioned men as the face of hip-hop lore, women continue to rise within the space. Kathy Iandoli, author of God Save the Queens, co-penned Lil’ Kim memoir, The Queen Bee, expected to release in 2025. This October, music journalist Sowmya Krishnamurthy will deliver Fashion Killa: How Hip-Hop Revolutionized High Fashion. In her forthcoming book debut, Ladies First, writer Nadirah Simmons credits women pioneers for their contributions to hip-hop. These are just a few works from a legacy of impactful hip-hop reads by women, like Kim Osorio’s tell-all Straight from the Source, Sophia Chang’s memoir The Baddest Bitch in the Room, and Angie Martinez’s autobiography My Voice.

To honor women scribes in hip-hop culture, ELLE.com spoke to eight authors, including the aforementioned Hope, Fitzgerald, Iandoli, and Krishnamurthy, along with Angie Thomas, Cristalle “Psalm One” Bowen, Mecca Jamilah Sullivan, and Sesali Bowen.

Meet the Authors

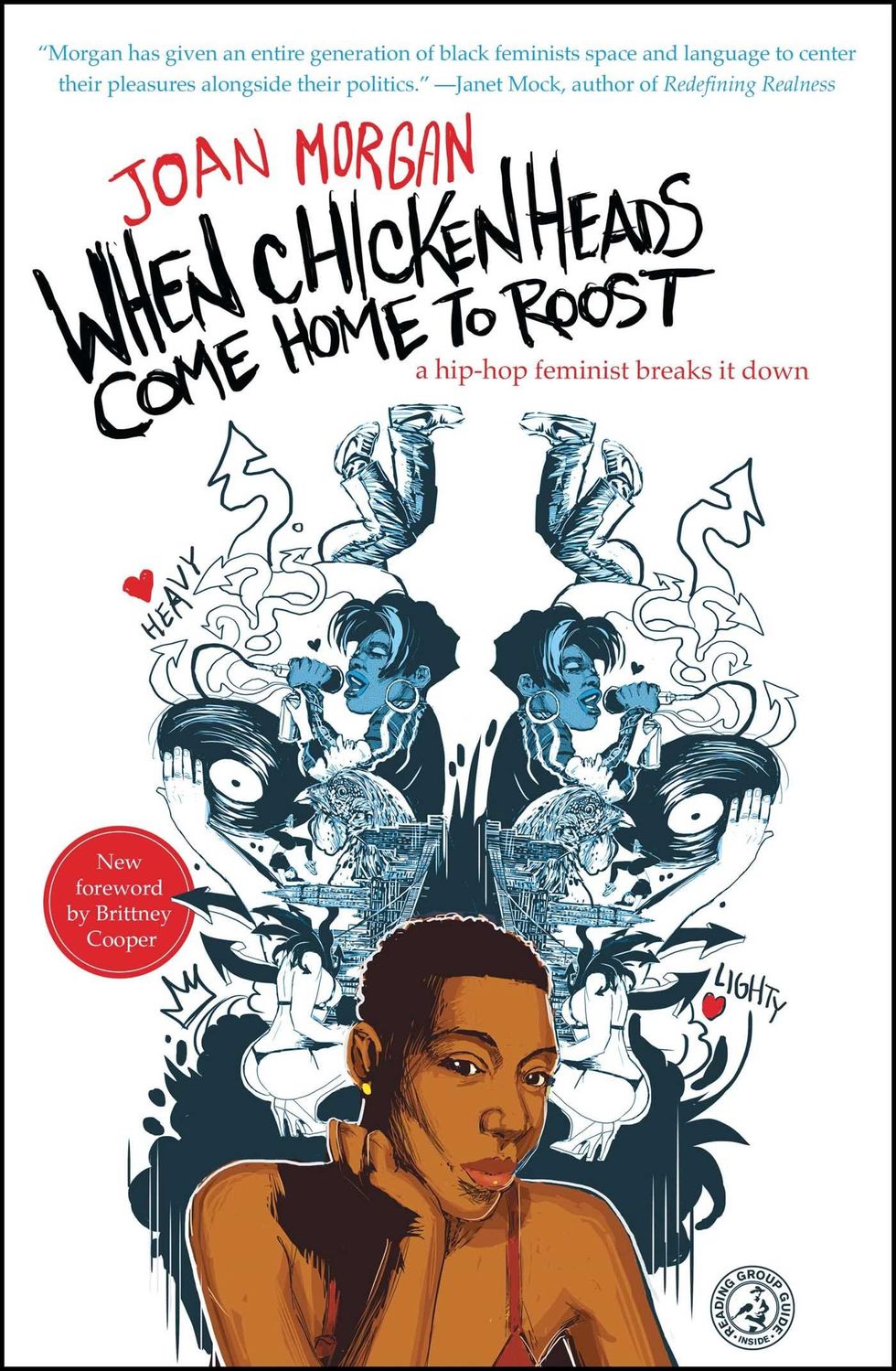

Angie Thomas’ On the Come Up follows fictional 16-year-old femcee, Bri, whose dad, an underground rapper, died before he made his career breakthrough. Carrying her father’s torch, Bri faces conflict when her song goes viral amid her family’s financial strain. The high schooler is faced with the opportunity to strike big, although success isn’t promised due to her upbringing. In 2022, On the Come Up was adapted into a film, the directorial debut of actress Sanaa Lathan.

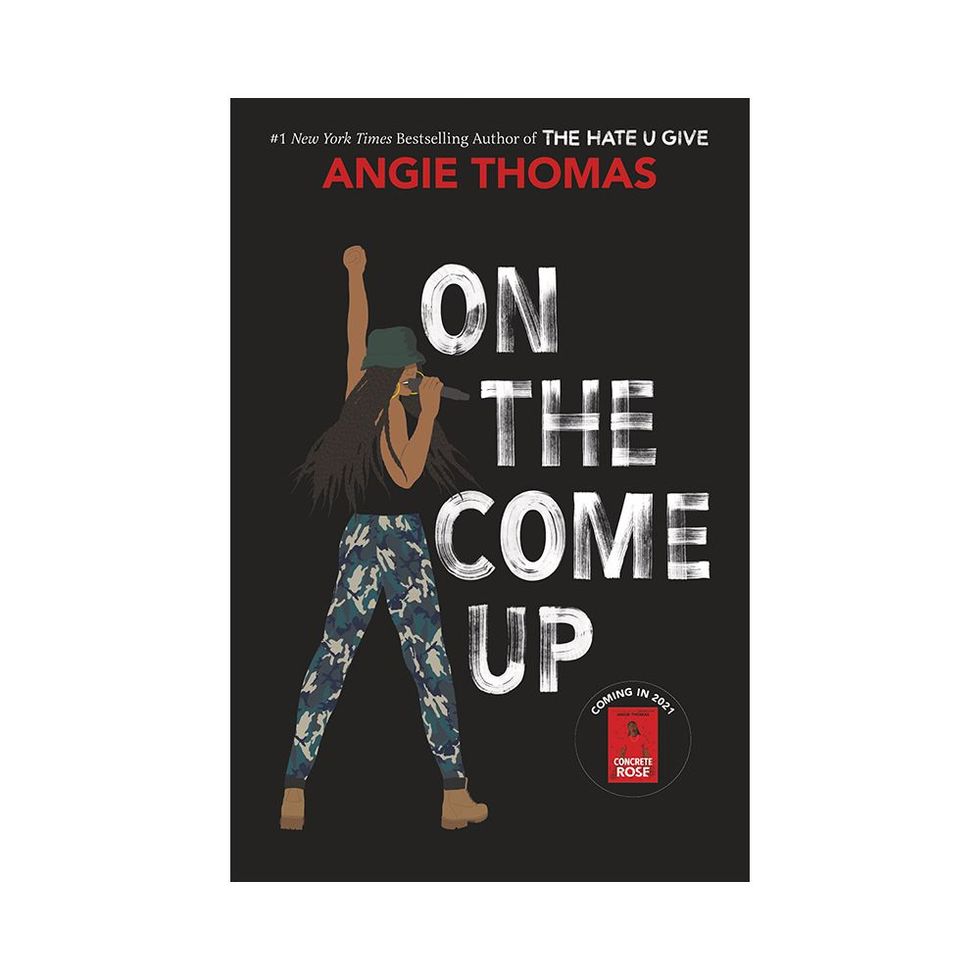

Clover Hope’s The Motherlode: 100+ Women Who Made Hip-Hop, is precisely what the title suggests: an homage to 100-plus female rappers across interviews and personalized explorations. Accompanying the women’s tales of triumph and underestimation are eye-catching illustrations by multi-disciplinary artist Rachelle Baker. Hope also narrates the audiobook on Audible alongside MC Lyte, Nia Long, Lauren London, and more, in addition to archival footage and music snippets to make The Motherlode an immersive experience.

Cristalle “Psalm One” Bowen’s Her Word Is Bond: Navigating Hip Hop and Relationships in a Culture of Misogyny, gets frank about the rapper’s lived experiences. The Chicago wordsmith opens up about being a queer artist, also retelling her plight with former label Rhymesayers Entertainment. Also a guidebook for aspiring independent artists, Bowen gives readers the real on the hardships and mistreatment that women endure in hip-hop.

Kathy Iandoli’s God Save the Queens: The Essential History of Women in Hip-Hop breaks down the misconceptions about women in hip-hop. A veteran music journalist, Iandoli challenges the notion that women should be disregarded in the genre, reintroducing the innumerable female emcees that made hip-hop a global phenomenon.

Kiana Fitzgerald’s Ode to Hip-Hop: 50 Albums That Define 50 Years of Trailblazing Music is a vividly illustrated coffee table book that chronicles fifty albums that have changed the course of hip-hop. Amongst albums from Lil Wayne, Megan Thee Stallion, Drake, Lauryn Hill, and more, the book reads like an album, with “interludes” and anecdotes on spotlighted artists and cultural movements.

Mecca Jamilah Sullivan’s Big Girl: A Novel brings ’90s hip-hop to life in a coming-of-age tale. Young Malaya Clondon attends a predominately white school and experiences body shaming due to her weight. As Malaya moves through adolescence, she finds refuge in music from The Notorious B.I.G., Lil’ Kim, and Aaliyah, and grows to defy expectations.

Sesali Bowen’s Bad Fat Black Girl: Notes from a Trap Feminist is a humorous and truthful read that challenges our comfortability with the appropriation of marginalized identities. Both diaristic and offering cultural commentary, Bad Fat Black Girl tackles sex work, misogyny, fatphobia, and more within the context of hip-hop, which she expands as a co-host on the podcast Purse First.

Sowmya Krishnamurthy’s Fashion Killa: How Hip-Hop Revolutionized High Fashion gives a “cinematic narrative” on the hip-hop icons that reinvented high-end fashion. In conversation with hip-hop artists, designers, stylists, and more, the book intersects the genre with contemporary fashion, and is a chronology of hip-hop’s B-boy origins to multi-hyphenate visionary Pharrell Williams’ being named Men’s Creative Director at Louis Vuitton.

On the Foundations of Their Respective Books:

Angie Thomas: “I was specifically thinking about young adult music books. A lot of them were about other genres such as pop, rock or even country, and I could not find many, if any, at that time that were about hip-hop or young rappers. A lot of times, when hip-hop was present in a young adult novel it would just be like, ‘Oh this is what the cool kids are listening to.’ It’s that stereotype of, ‘There goes that cool Black kids in school listening to hip-hop.’ But that’s the music I grew up on. For a long time, hip-hop was my literature, so I wanted to finally pay homage to that in a book.”

Clover Hope: “I think I just noticed that a lot of—at least history of hip-hop—would kind of tell the story or narrative of hip-hop from a man’s perspective, because those were the people either right writing these histories or kind of mapping them out. For me, I watch a lot of documentaries and hip-hop chronologies and I’d always notice that there weren’t enough women highlighted, or I would just always leave wanting more. What these stories tend to leave out is just the impact, because I don’t know if male hip-hop fans necessarily think that deeply about the women besides the ones that they already know.”

Cristalle “Psalm One” Bowen: “When I began writing my memoir, it wasn’t even really a memoir, it was more of an editorial sort of piece. If you notice the first couple chapters, I’m sort of laying out the soundscape of the time and what those albums and songs meant to me as a young girl growing up in Chicago. It’s just the feel, really, of growing up in Chicago and having people like Common, Twista, Crucial Conflict, and Infamous Syndicate. I wanted to speak about them, but as I started going through the timeline, I realized, ‘When I got to college, my life started to get kind of spicy.’ Hip-hop came to me when I was a student and a fan at first, but then I started rapping and taking myself a little bit seriously. The music and my life were so intertwined.”

Kathy Iandoli: “I conceptualized [God Save the Queens] in 2008, and at that point, there was very minimal presence of women in hip-hop and hip-hop books. If anything, they were like a footnote, and they always start at a very specific point which was usually around 1989, like the “Ladies First” era. It would hover over until the Lil Kim era and then it was just like, stop. I had spoken with agents and publishers, and they quite frankly didn’t see a narrative, which I thought was wild. I feel like contrary to popular belief, we weren’t at a dead standstill until Nicki [Minaj] came. There were artists, the labels just weren’t funding them. It was around 2018 that I started to talk to publishers again, had my agent, and really brought it to the table—there had never been a book about women in hip-hop, like a full history. I think it was a matter of the publishing industry recognizing the trend, even though the trend was in everyone’s faces from day one. But I think I had to wait for the industry to be ready to create that first book.”

Kiana Fitzgerald: “The major factors that I wanted to consider were how an album shifted the culture—whether that’s fashion or philosophy or the way that we interact with each other—and how an album influences other musicians, other hip-hop artists. Then also, how did it impact hip-hop the next year, the next decade, the next 25 years? Some of these albums are very fresh, so the criteria is a little bit more malleable for the more recent works, but for everything else I really wanted to look at like, ‘What did this album say to this generation? What did it say to the next generation?’ A lot of folks can kind of get by [without] knowing their history, but I think in order to really be a true student of hip-hop, a true person who wants to contribute to the furtherment of the genre, it’s important to know your history.”

Mecca Jamilah Sullivan: “Malaya is coming of age in 1990s Harlem, New York. The identity of the neighborhood is changing and as a teenager, her identity is coming into its own. She’s making space for herself for who she is and especially for her body; she’s a big Black queer girl. So in the midst of all of that change, hip-hop, especially ‘90s hip-hop, comes in to guide her in many ways through figuring out who she is, who she wants to be, especially in terms of gender and sexuality. Hip-hop, especially in that moment, has this irreverence, a raunchiness, this refusal to acquiesce to norms and standards around sexuality. It’s sort of hotly contested in some ways that her body and her identity are contested. She finds a sense of belonging in ’90s hip-hop. Figures like Biggie, Lil’ Kim, Aaliyah, she finds this really affirming and a way of sort of seeing future visions of herself.”

Sesali Bowen: “Joan Morgan coined the term ‘hip-hop feminism,’ and I really saw [Bad Fat Black Girl] as a direct update to [When Chickenheads Come Home to Roost]. It’s 30 years later, and trap feminism, I grew up on this subgenre of hip-hop and [have] a book of essays and it combines that memoir format with cultural commentary. Black Ratchet Imagination by LaMonda Horton-Stallings broke something open for me when I was in grad school, in terms of thinking about how some of the imagery that is painted in trap music. It’s so subversive to heteronormativity and gender roles, and that became a framework for me to start thinking differently about this.”

Sowmya Krishnamurthy: “Hip-hop and fashion have been such an integral part of each other since the beginning. There really wasn’t a comprehensive anthology that spanned hip-hop’s history, and really delved into all of the important milestones and individuals and nuances of the topic. Oftentimes when people speak about hip-hop and fashion, it’s really kind of from a surface level or a cursory level. So it’s focusing on a handful of artists and a handful of designers, but I really wanted to delve into the history, delve into this socioeconomic context, as well as highlight certain voices who might be unsung heroes in this narrative.”

On the Elements of an Exemplary Hip-Hop Book:

Thomas: “If you’re going to have a book about hip-hop, you need to figure out what region of hip-hop you’re writing about. Southern hip-hop versus New York hip-hop are two very different things. But I think it needs to represent the culture and all of its beauty and blemishes. I think that it needs to speak to the heart of it and I think that it needs to be unfiltered. I think it needs to be as real as it gets because that’s what hip-hop is. Rappers taught me to say what’s on my mind, to write what I feel, to find my voice.”

Cristalle Bowen: “One thing that I notice in some of the hip-hop memoirs that I’ve read, these people write about themselves like they never really did anything too wrong. It’s sort of this glossing over events and lessons that I think are more realistic when you speak about them from a vulnerable place. I had already been professionally embarrassed when it came to hip-hop, so I was like, ‘I should write my own narrative since other people like to tell my story.’”

Sullivan: “Hip-hop—in addition to being this cultural phenomenon—it’s a critical genre. It’s a genre that has always had something to say about inequities, about power, about oppression, about race, gender, class, sexuality, ability and disability, fatness… A quintessential book on hip-hop would center how it uses those storytelling traditions to critique and make comments on the world around us.”

On What Women Offer to Hip-Hop Culture:

Thomas: “The truth of the matter is, women are one of the most dominant forces in hip-hop. We’re all through the culture, we’ve been there from the beginning, and so often we’re the most disrespected in it. So I wanted to show that you have this young girl who has this love for hip-hop and lyricism. She studies the greats, she wants to be one of the greats. I wanted to pay homage to that love, but I also want to pay homage to the women of hip-hop who have built the foundation, because so often they’re so overlooked and it’s so disrespectful. It was important to kind of take that back but also to show, like, ‘Hey, we’re here. We’ve always been here and we’re forced to be reckoned with so you better recognize.’”

Hope: “I didn’t realize how many of them just felt a little bit forgotten, or were just happy to leave the industry. Some just wanted more recognition or just wanted a shot, like The Lady of Rage. She wanted a better chance than she got and that she deserved. Some of them, like Solé, were happy to leave behind something that was toxic. I got a better sense of how it’s very hard to stay hot in hip-hop. In this environment that is toxic to women, it literally drives women away from staying in it. Not that I didn’t know, but there’s almost a boiling point that they reach where it’s like, ‘This is too destructive.’ That says something about how you can protect them now, like Megan Thee Stallion—she’s been through the ringer. We are lucky to be able to listen and see her evolve. It’s almost like a love thing where you are choosing it everyday; women are choosing to love this and that needs to be recognized.”

Sesali Bowen: “I think [sex positive female rappers] have such a huge opportunity to destigmatize sex work; they are creating a culture in which women’s bodies and women’s sexuality aren’t sites of shame.. It’s extremely dangerous for sex workers to just do their jobs, and a big part of that is because of the stigma. I think the way Sukihana talks about being a sex worker while also choosing how she talks about it and still presenting herself as a very multifaceted person… She refuses to allow people to only view her as a sex worker, as if that’s the only part of her identity that matters.”

On Rappers Who Guide Their Storytelling:

Hope: “MC Sha-Rock, she really pushed herself to the forefront as claiming to be the first female emcee. Obviously there’s a debate around that, but she was part of the Funky Four Plus One, who I have heard of. But in the process of researching and speaking to her and speaking to other emcees who were popular or active in the ’70s, I’d definitely got a deeper understanding of her life story, and just how important she was to this just formation of hip-hop. … Her story flew under the radar, and I felt like, ‘Wow, if I’m neglecting this, then there’s definitely a swath of hip-hop fans who do not know this history.’”

Iandoli: “Hearing [Lil’] Kim tell her stories, and hearing what Kim had to go through, and what Kim continues to do in this space, it just blew my mind. I’ve always been a Lil’ Kim fan. I’ve known Kim for a long time, but the thing that I love about this story is that I feel like no one is going to expect some of the things that Lil’ Kim was actually a huge part of. You look at Lil’ Kim—fashion icon, unapologetic lyricist, protege of The Notorious B.I.G.—but there’s just so many different layers to the story that Kim goes into and what she had to do to get and stay on top. That’s why she’s out here and selling out shows and still is the blueprint. That’s the best part about it—you’re not talking about a story in the past tense; it’s still actively happening.”

Sullivan: “We’re seeing more space for women artists, for Black queer artists and also artists of different genders and different sexual identities to really explore various aspects of intellectual life and their bodily life. I look to Missy Elliott as a true hip-hop icon; she has made space for women rappers doing gender and embodiment in several different ways. These things are deeply meaningful from Malaya as a fat Black girl growing up in a time where you don’t really have language like ‘body positivity,’ or even queerness, like gender variance. She doesn’t have that language in the ’90s, but hip-hop offers her a way in to living into those aspects of herself even without the external language to support her.”

Krishnamurthy: “When it came to organizing the book [Fashion Killa], I wanted to make sure that each chapter could be standalone, but they also bled into each other, and you would see certain recurring characters; whether it be someone like a Lil’ Kim or Sean “Puffy” Combs, who kind of are important in different eras and in different facets of the story. It was definitely a big undertaking but, I think that can be really exciting when there isn’t really a blueprint to work with; you get to create it.”

Interviews were condensed and edited for clarity.

Jaelani Turner-Williams is an Ohio-raised culture writer and editor. She specializes in digital and print media, and has written for Complex, Dwell, Rolling Stone, Teen Vogue, and other outlets. She is executive editor of biannual fashion, lifestyle and culture publication Tidal Magazine.

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.