Women in rap are beginning to speak their truth in their own voice, inadvertently subverting sexism in the art form.

To pay tribute to five decades of reporting, rebelling and truth-telling, From the Vault includes some of our favorite feminist classics from the last 50 years of Ms. For more iconic, ground-breaking stories like this, order 50 YEARS OF Ms.: THE BEST OF THE PATHFINDING MAGAZINE THAT IGNITED A REVOLUTION (Alfred A. Knopf)—a stunning collection of the most audacious, norm-breaking coverage Ms. has published.

Like many Black feminists, I see sexism in rap as a necessary evil. In a society plagued by poverty and illiteracy, where young Black men are as likely to be in prison as in college, rap is a welcome articulation of the economic and social frustrations of Black youth.

It offers the release of creative expression and historical continuity; it draws on precedents as diverse as jazz, reggae, calypso, Afro-Cuban, African and heavy metal, and its lyrics include rudimentary forms of political, economic and social analyses.

But though there are exceptions, like raps advocating world peace (the W.I.S.E. Guyz’s “Time for Peace”) and opposing drug use (Ice-T’s “I’m Your Pusher”), rap lyrics can be brutal, raw and, where women are the subject, glaringly sexist.

Though styles vary—from that of the X-rated Ice-T, to the sybaritic Kwamé, to the hyperpolitics of Public Enemy—what seems universal is how little male rappers respect sexual intimacy and how little regard they have for the humanity of the Black woman.

At present there is only a small platform for Black women to address the problems of sexism in rap and in their community. For a Black feminist to chastise misogyny in rap publicly would be viewed as divisive and counterproductive. The charge is hardly new. Such a reaction greeted Ntozake Shange’s play For Colored Girls Who Have Considered Suicide, When the Rainbow Is Enuf, my own essays in Black Macho and the Myth of the Superwoman, and Alice Walker’s novel The Color Purple—all of which were perceived as being critical of Black men.

For a Black feminist to chastise misogyny in rap publicly would be viewed as divisive and counterproductive.

Rap is rooted not only in the blaxploitation films of the 1960s but also in an equally sexist tradition of Black comedy. In the use of four-letter words and explicit sexual references, both Richard Pryor and Eddie Murphy, who themselves drew upon the earlier examples of Redd Foxx, Pigmeat Markham and Moms Mabley, are conscious reference points for 2 Live Crew. Black comedy, in turn, draws on an oral tradition in which Black men trade “toasts,” stories in which dangerous badmen and trickster figures like Stackolee and Dolomite sexually exploit women and promote violence among men.

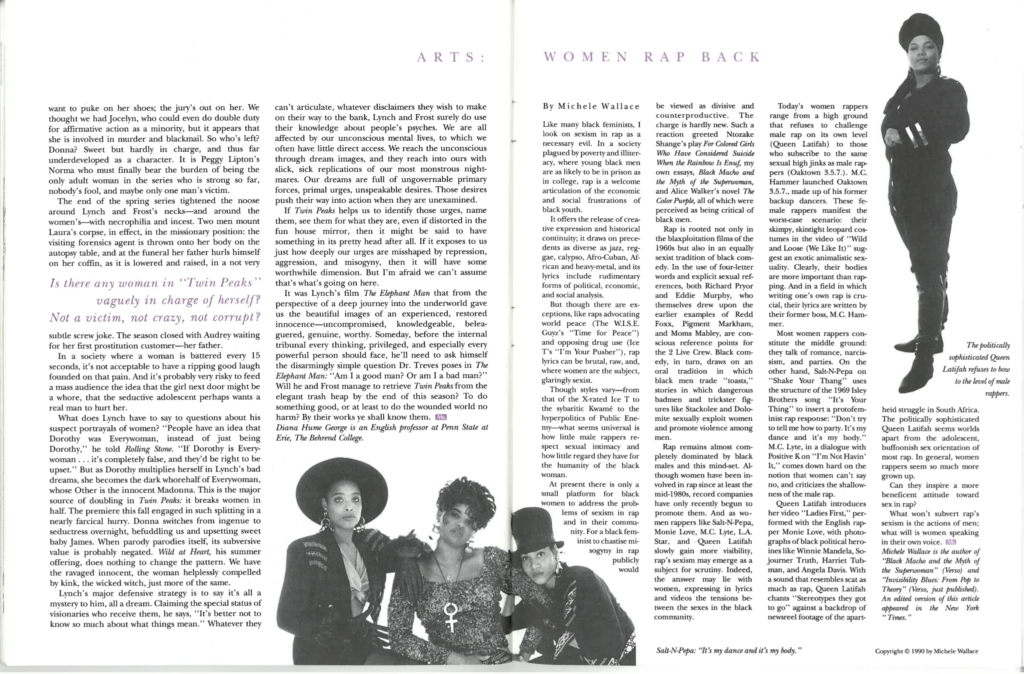

Rap remains almost completely dominated by Black males and this mindset. Although women have been involved in rap since at least the mid-1980s, record companies have only recently begun to promote them. And as women rappers like Salt-N-Pepa, Monie Love, MC Lyte, L.A. Star and Queen Latifah slowly gain visibility, rap’s sexism may emerge as a subject for scrutiny. Indeed, the answer may lie with women, expressing in lyrics and videos the tensions between the sexes in the Black community.

Today’s women rappers range from a high ground that refuses to challenge male rap on its own level (Queen Latifah) to those who subscribe to the same sexual high jinks as male rappers (Oaktown’s 3.5.7). MC Hammer launched Oaktown’s 3.5.7, made up of his former backup dancers. These female rappers manifest the worst-case scenario: Their skimpy, skintight leopard costumes in the video of “We Like It” suggest an exotic animalistic sexuality. Clearly, their bodies are more important than rapping. And in a field in which writing one’s own rap is crucial, their lyrics are written by their former boss, MC Hammer.

What won’t subvert rap’s sexism is the actions of men; what will is women speaking in their own voice.

Most women rappers constitute the middle ground: They talk of romance, narcissism and parties. On the other hand, Salt-N-Pepa on “Shake Your Thang” uses the structure of the 1969 Isley Brothers song “It’s Your Thing” to insert a protofeminist rap response: “Don’t try and tell me how to party. It’s my dance and it’s my body.”

MC Lyte, in a dialogue with Positive K on “I’m Not Havin’ It,” comes down hard on the notion that women can’t say no and criticizes the shallowness of male rap.

Queen Latifah introduces her video “Ladies First,” performed with the English rapper Monie Love, with photographs of Black political heroines like Winnie Mandela, Sojourner Truth, Harriet Tubman and Angela Davis. With a sound that resembles scat as much as rap, Queen Latifah chants, “Stereotypes they got to go” against a backdrop of newsreel footage of the apartheid struggle in South Africa.

The politically sophisticated Queen Latifah seems worlds apart from the adolescent, buffoonish sex orientation of most rap. In general, women rappers seem so much more grown up.

Can they inspire a more beneficent attitude toward sex in rap?

What won’t subvert rap’s sexism is the actions of men; what will is women speaking in their own voice.

Up next:

U.S. democracy is at a dangerous inflection point—from the demise of abortion rights, to a lack of pay equity and parental leave, to skyrocketing maternal mortality, and attacks on trans health. Left unchecked, these crises will lead to wider gaps in political participation and representation. For 50 years, Ms. has been forging feminist journalism—reporting, rebelling and truth-telling from the front-lines, championing the Equal Rights Amendment, and centering the stories of those most impacted. With all that’s at stake for equality, we are redoubling our commitment for the next 50 years. In turn, we need your help, Support Ms. today with a donation—any amount that is meaningful to you. For as little as $5 each month, you’ll receive the print magazine along with our e-newsletters, action alerts, and invitations to Ms. Studios events and podcasts. We are grateful for your loyalty and ferocity.

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.