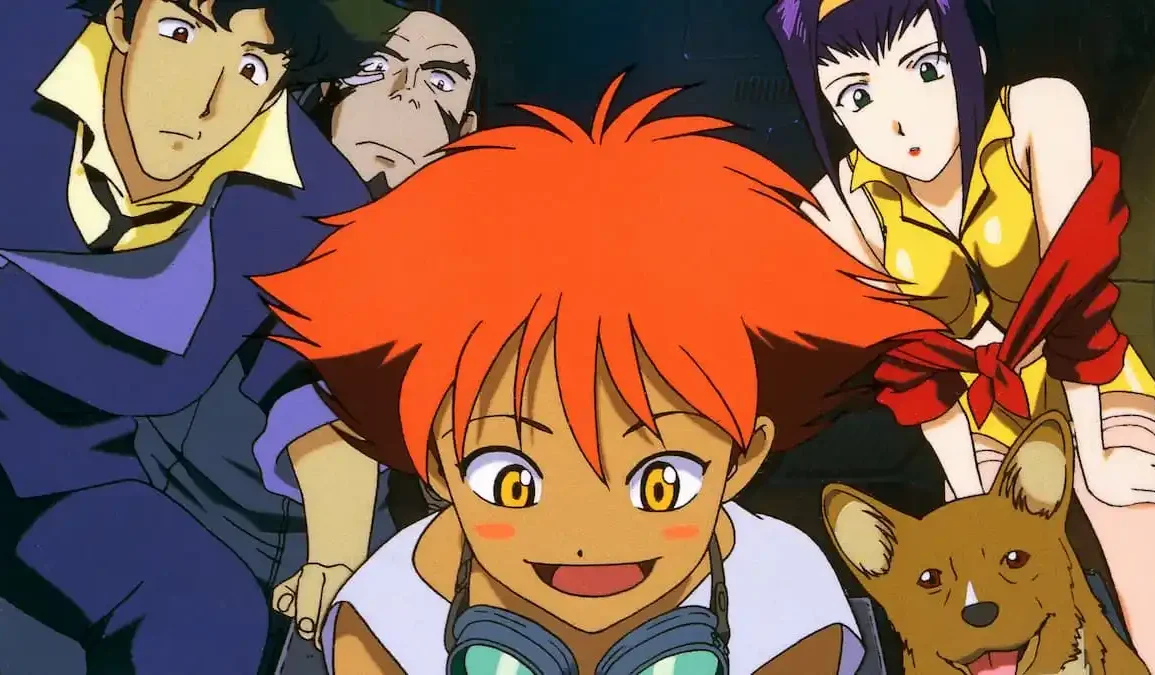

Cowboy Bebop is a masterpiece of a series. That’s not even an opinion; it’s simply a culturally accepted fact. Bebop is known as a “gateway anime,” a series responsible for hooking scores of Westerners onto the larger medium.

The animation, even 25 years later, still looks stunning. The broad, often subtle strokes of the larger story, which floats over episodic bounty hunter mayhem, still remains gripping. And the music has taken on a life of its own, iconic in its own right. Middle school jazz bands around the States continue to work “Tank!,” the show’s theme song, into their repertoire.

Trying to pin down Kanno’s style does the score a disservice. As the name of the series suggests, the score heavily features jazz, as performed by Kanno’s big band, The Seatbelts. The score was recorded in New York, and members of the New York Seatbelts have gone on to become some of the biggest names in modern jazz. But Kanno’s score also includes an organ-infused rock ballad, hints of electronica, astonishing a cappella choirs, and even hints of poppy new age.

Yoko Kanno’s score is, two and a half decades later, widely considered one of the greatest anime soundtracks ever made. The Cowboy Bebop score alone has made her a deeply revered figure among the anime community, on the level of Studio Ghibli’s cornerstone composer Joe Hisaishi. That’s why it was a rather big deal that on the evening of November 16, 2023, Crunchyroll and Town Hall helped organize the first-ever live scoring of Kanno’s music to four curated episodes of Cowboy Bebop—and why it was an even bigger deal when, as a complete surprise to the audience, Yoko Kanno herself was there.

Yoko Kanno’s message to New York

To say the audience roared with applause would be an understatement. Kanno, awash with a very loud love she was not expecting, seemed not to have prepared a speech. We learned that the score for Cowboy Bebop was recorded in New York, and in reflecting on her daily routine in that time, Kanno considered her salads and exclaimed, “I like honey mustard,” her hands triumphantly in the air.

But that does not mean Kanno didn’t have things she wanted to say. She wanted to memorialize Keiko Nobumoto, who wrote the script for Bebop and passed away in 2021. She then pointed out that Yuuho Iwasato, the lyricist for the ending theme for the show, “The Real Folk Blues,” was also a woman. Between herself, the scriptwriter, and the lyricist for a quintessential song, Kanno came to a pronouncement I will never forget: “Women made Cowboy Bebop cool.”

That declaration was even more powerful because the ensemble performing her score that evening was the Sinfonietta, an all-female and majority women of color ensemble. And they were conducted by the ensemble’s founder, Macy Schmidt, who is the first woman of color orchestrator in Broadway history. There were only women on that stage, playing a highly beloved work composed by a woman who had just said one of the most influential anime in history was “cool” because of women.

The crowd exploded in cheers.

On women in music

I, too, am a musician—and often in circles that I’ll call “jazz and jazz adjacent.” The percentage of shows where I have thought to myself, “Ah, I’m the only non-male on the bill,” is well over half. It’s a bizarre feeling, to be in a group of about a dozen people presenting something where you alone are the onstage representative for about 50% of the earth’s population—again and again. You begin to wonder why this keeps happening. Is the kind of music I’m playing (rock, jazz) too male-coded? Is it this city’s scene? Is it me?

It’s a conundrum for the ages, one that gets hot takes galore. In my lived yet unacademic opinion, the idea of “missing women” in an arts scene largely comes down to whether or not a space welcomes them, in both an institutional sense and a “vibe check of the room” sense. Jazz is a very male-coded genre—when I was going to jam sessions around 2011, people usually assumed I was either a singer or, if they saw the guitar on my back, someone’s diligent girlfriend. These perceptions are getting better, especially after me too burst the conversation wide open. But sometimes the quiet sexism—like simply not booking the equally talented female horn player—is the hardest to confront.

All of this is why the performance of Kanno’s score by the all-female Sinfonietta felt like a blast of fresh air. Contrary to what we’re often led to believe, the fans watching the Cowboy Bebop performance at Town Hall did not care about the makeup of the performers. They cheered with unbridled enthusiasm after every solo, every song. I saw a man two rows ahead of me react to “Ave Maria” with more excitement than I have ever seen a human being react to a piece of classical music. All that mattered was that The Sinfonietta killed it.

The power of example truly can’t be overstated. If, especially as a child, you see someone who shares a key characteristic with you doing something exception, you think, “Wow, maybe I can do that one day, too.” Maybe I’ve watched too many anime, but that spark of inspiration can have a huge domino effect. That’s why keeping an eye on programming is so important.

It’s also why, as a college junior fighting my way to class during Midwest winters, Yoko Kanno’s score to Cowboy Bebop became a balm. It was the piece of music I loved most, and “even though” it was written by a woman, thousands and thousands of people loved it, too. I was discovering that, more than many of my peers, I was having to create my own performance opportunities (gender wasn’t the only reason for this—my playing style was also getting more experimental, largely as a revolt against being dismissed as the “cute little guitar player”). Listening to that score told me, “I did it, and you can, too.”

At the end of the night, conductor Macy Schmidt proposed playing “the greatest theme song in history” one last time. The crowd at Town Hall ecstatically screamed their excitement and sat back down in their seats from their standing ovation.

(featured image: Sunrise)

Have a tip we should know? [email protected]

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.