Pharrell Williams has a pimple. There’s a bandage on his chin, and immediately after introducing myself, I ask him, “What happened?” And he says in the nonchalant, melodious voice I’ve heard approximately 1 billion times on speakers and in headphones but did not expect to be so perfectly his in person: “Oh, just a pimple.”

He just turned 50 and his skin has the texture and tone of a nourished and well-hydrated 22-year-old. Upon clocking the bandage, I thought maybe one of his four children had caught him with a headbutt. Maybe he fell skateboarding. I did not in a thousand years expect him to tell me that under the bandage he had hidden a pimple. And immediately I feel like a jerk for calling attention to it.

But Pharrell does not seem perturbed by my comment, or by the blemish or the bandage. He is full of humility. He is open and honest and ready to share himself—and his imperfections—with the world.

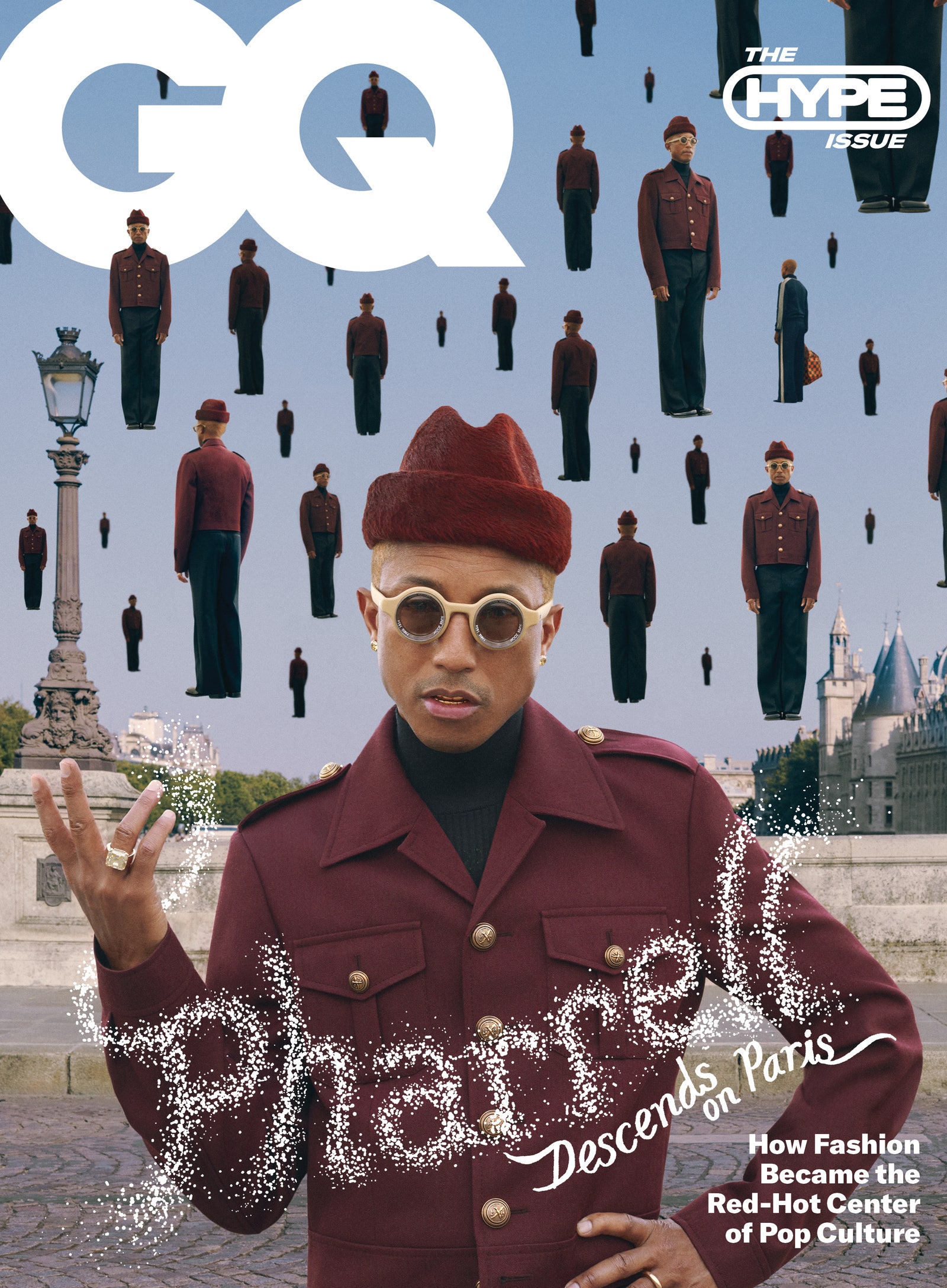

We were in a vast parking lot in Pharrell’s hometown of Virginia Beach, amid a carnival of trailers and trucks that served as the backstage area for the now-annual three-day music festival called Something in the Water that he hosts right on the sand. It was late April, a momentous time for Pharrell. He was just two months into his new job as the men’s creative director of Louis Vuitton, and enormous questions were swirling about what the superstar producer would do with the keys to a global luxury superbrand.

His appointment had put to rest a year of gossip and speculation about who might fill the role left vacant after Virgil Abloh’s death in 2021. Some expected that the position would be used to elevate one of the young, overachieving fashion-school graduates who had found success at his or her own brand. Others guessed that the job would go to a well-known designer. Nobody seemed to be floating Pharrell’s name. When the news broke, on Valentine’s Day, it was seismic. One of the world’s most famous people was being invited by one of the world’s biggest brands to reshape the business of luxury fashion.

Never before has such a famous artist or a musician—or a celebrity of any stripe—been appointed to a position of such distinction in the luxury business. And yet, the moment shouldn’t have been a total surprise. We’ve been living in fashion’s celebrity era for a decade now. Brands are working to establish something bigger and more loyal than a customer base: They want a fan base. A whole world of people who follow what they do the way people follow Hollywood or sports, regardless of whether they can afford a bag.

Meanwhile, stars have bumped buyers and the press out of front-row seats at fashion shows, and replaced supermodels in campaigns. Collaborations between luxury brands and pop stars are ubiquitous. As priorities go, traction on social media is just as important as the cut and quality of the clothes.

In light of these developments, Pharrell’s appointment seemed like the logical next step in the quickening union between fashion and celebrity culture. This was the point made at the time by cynics who suggested that the job amounted to a kind of vanity role for Pharrell and a marketing ploy for the brand. But the true scope of Louis Vuitton’s bet on Pharrell is grander than we could have realized back when it was first announced.

I wanted to know, on that afternoon in Virginia, how Pharrell was faring under the expectations of the new job. He was toiling on what would become his first collection—which he’d later unveil in dramatic fashion in Paris in June—and over those intervening months, I went on a kind of journey with Pharrell. From his hometown in Virginia Beach, to his new home in Paris, and across several intimate conversations in his studio and showroom, I was permitted to see what he was cooking up. More than that, though, I began to understand how it is that Pharrell is driving a paradigm shift, not just in the business of designing and selling luxury goods but in the whole wild, symbiotic swirl of pop culture and fashion.

And so the pimple on Pharrell’s chin—particularly, his instant openness and honesty about it—felt like an encouraging omen.

After we put the bandage incident behind us, Pharrell and I sat down on a couple of stools under the shade of a canopy that had been set up between two trailers. Pharrell and his family have been spending most of their time in Paris since his appointment, but they’d all come to the festival together—his wife, Helen, their 14-year-old son, Rocket, and the triplets he and Helen had in 2017. As we chatted, they all hung out nearby in the artist compound—a few hours later, Pharrell would take the stage with Pharrell’s Phriends and put on a two-hour headlining performance featuring a melange of other artists including Diddy, M.I.A., De La Soul, Busta Rhymes, and A$AP Rocky.

Pharrell is a prodigious multitasker—endlessly juggling a music career with a skin care line and a restaurant and a hotel and collaborations with Adidas and one of LVMH’s newest high-value acquisitions, Tiffany & Co.—but given the enormousness of the new job in Paris, I was amazed he was at the festival, in mind and body, hosting and performing. But he assured me that he’s still working on the LV collection remotely. “We’re in constant contact,” he says of himself and his team back in the Paris studio. “It’s crazy what we have coming. I pushed it in every aspect, every category. I pushed it.”

What became apparent to me over the course of a few days in Virginia Beach during Something in the Water was that Pharrell wasn’t just toiling on LV projects remotely. His work for the brand was all around us. My initial presumption—that he’d taken time off from his new job to tie up the loose ends of his old job—reflected a misunderstanding in what was really going on here.

While the fashion world was awaiting Pharrell’s first show in June to see his vision for the brand, the people of Virginia Beach were already experiencing it in April. Just by being there, they were getting a taste for what Pharrell had in mind for his debut: The collection he would present in Paris is titled LVERS, as in “Virginia is for….” He was here not just to satisfy the thousands of fans who came out for his music; he was here to introduce them—or reintroduce them, as the case may be—to Louis Vuitton, to Pharrell’s Louis Vuitton. And for him, the mission was clear: “From Paris to VA, VA to Paris,” he says, “that’s literally the narrative. All of this is seeding that.” For him and for his fans, the music and the clothes are part of one body of work. “It’s a part of my story,” he says.

Not far from where we chatted, brisk business was being done inside a VIP tent over by the stage, where a Louis Vuitton pop-up shop had been erected. It wasn’t selling festival merch, it was selling what were essentially early pieces of Pharrell’s first LV collection—T-shirts, hoodies, and denim jackets with “Virginia is for LVovers” and “I LV VA” graphics. A constant frenzy of fans moved through the small temporary shop, snatching up $860 T-shirts and $1,310 hoodies.

Down the beach, Pharrell had a 30-foot-tall sandcastle built, designed to look like one of the Pyramids of Giza had been made from Louis Vuitton steamer trunks, like the ones the brand sells for around $46,000. What could be seen as a monument to corporate marketing was met by selfie takers with giddy delirium and enormous gratitude. There is no Louis Vuitton store in Virginia Beach. It isn’t a fashion capital. But that doesn’t mean, Pharrell seemed to acknowledge, that the people here don’t want to participate in the luxury-fashion spectacle. I took Pharrell’s pyramid as a symbol that he intends to widen the aperture of LV. He is in a position to democratize the notion of who ought to be participating in luxury fashion and where and how. There may not be a huge luxury-fashion market in Virginia Beach, but there are fans. And Pharrell is going to include them. He emphasized that when we spoke weeks later in Paris: “You could feel how much those people appreciated having something there, right?”

Pharrell grew up a mile from the boardwalk. As a teenager he met and eventually began making music with the rapper Pusha T, another Virginia Beach local. “When I look at Pharrell and I look at what he does and what he’s done throughout his career, it has all been centered around hometown pride,” Pusha tells me. “We were dreamers. We were explorers. And it just shows that regardless of where you’re from, if you keep dreaming and keep being passionate about your craft, it’ll pay off.”

Pharrell knows his journey is instructive, that with this new role he embodies a powerful message about the liberating, transporting power of art and creative expression. The pyramid doesn’t mean go buy a Louis Vuitton trunk. It means, Pharrell tells me, “Dream big.”

Pharrell tells me that when the LV job was first broached, it seemed to come out of the blue. He was at his studio in Miami Beach, last December, when he heard from Louis Vuitton CEO Pietro Beccari. “It wasn’t an interview or anything,” Pharrell remembers. “It was like, ‘Will you accept this position? Will you accept this appointment?’ I’m looking at the water and I’m just like, ‘What?’ ”

Pharrell had been in talks with folks at LVMH about who might succeed Virgil Abloh—offering names and sharing opinions with, among others, Alexandre Arnault, a son and key lieutenant of founder Bernard Arnault—but Pharrell says he did not realize that he himself was being considered. He expected the choice to be Nigo, his longtime friend and collaborator who currently heads a different LVMH brand, Kenzo. “He’s my hero, he’s my brother, and he’s the general,” Pharrell tells me. “I’ve been championing him for a minute. And whenever me and Alexandre talk about LV, we would always just talk about different people. I’ve always been in the background, just advising. I never thought that it would be me.”

Pharrell had already worked directly with the house in a design capacity on three prior occasions. But the thought of running all of menswear was on a whole different scale. Beccari recalls that Pharrell figured the CEO was joking when he sent the first text about the job. “Ultimately, it was the perfect opportunity to work together again,” Beccari, who previously worked with Pharrell when running marketing and communications for Louis Vuitton, tells me in an email. “There was a natural and shared understanding of him coming back home.”

Pharrell’s first foray with the brand came nearly 20 years ago, after a chance meeting with Marc Jacobs at the opening of the Louis Vuitton store on 57th Street in Manhattan. Jacobs, who was the creative director at the time, complimented Pharrell on the sunglasses he was wearing, which had been designed by Nigo. The conversation led to an invitation for Pharrell and Nigo to work on a collection of LV sunglasses, which was released in 2004. Of the dozen or so styles they created, one, the Millionaires, was reinterpreted by Abloh during his time at LV, and reappears in Pharrell’s new collection. Jacobs and Pharrell continued to work together on a campaign for the house, in 2006, and a collection of fine jewelry that Pharrell co-designed in 2008.

“He was changing the paradigm,” Pharrell says about his experience working with Jacobs and LV. “At that time, musicians were only used here and there in campaigns, especially Black ones. And maybe we could use the clothes editorially, but there was no allowing people who looked like us to come in behind the curtain and go design and make things. Marc was first. He was the pioneer of that, and now you see that all over the place.”

“I was drawn to Pharrell by his music, then his style and his overall energy when we first met,” Jacobs tells me by email. “I truly believed the way forward at Vuitton was collaborating with other creatives, and that’s what Pharrell was, and still is, to me: authentically creative.”

Since those gigs, Pharrell’s creativity and curiosity have led him to all kinds of interesting fashion-world opportunities, including long-term collaborations with Adidas, Chanel, and Tiffany & Co. Sarah Andelman, founder of the influential French fashion boutique Colette, has collaborated with Pharrell numerous times, going back to his first Adidas collection, which he launched at her shop in 2014, and more recently as a curator for Pharrell’s Joopiter auction house. “He’s the same as the first time we met,” she tells me. “Very collaborative, very open-minded, very loyal.” She was, she tells me, “so, so, so happy” when she heard the news of his appointment at LV. “He knows he wants to make a community, to use it as a platform to bring artists or other creatives to the house.”

But Pharrell’s dalliances in fashion were, until now, part-time jobs. LV is the first brand to go all in on somebody like Pharrell. “It’s the first time someone has had the daringness to pick a real worldwide star to helm a house,” says Beccari of his decision to hire Pharrell.

It wasn’t that long ago that it seemed things were headed this way for a different, globally famous Black American artist and superproducer. It was no secret that Kanye West, now known as Ye, had his sights set on the heights of luxury fashion. And for a while there, it seemed like the big luxury fashion houses were interested in him too. It didn’t come to fruition. Instead, it was Ye’s protégé and right hand, Abloh, who brought a new level of cultural and celebrity connectivity, cachet, and presence to fashion at Louis Vuitton, and he had proved to be an amenable collaborator. He’s been celebrated widely since his death for opening the doors to the industry for other creatives of his ilk—most of whom do not have formal fashion training—and it seems he did in fact open the biggest door of them all for Pharrell to step through. The long-held dream—one that may have once been Ye’s—of a monumental convergence between the cultural prowess of modern music stars and the commercial might of the luxury industry appears poised for fulfillment.

“He has 13 Grammys and even Oscar nominations,” says Beccari. “One could say he has a Midas touch. So, as a creative director, while it’s an experiment, I think it will be a successful one.”

In June, I reconnected with Pharrell in Paris, at the LV headquarters just across the street from the Pont Neuf in the 1st arrondissement. In the weeks since I had last seen him, Pharrell and his team had been working to finish their first collection. When I arrived at the studio space, photos of most of the final looks were arranged on a whiteboard.

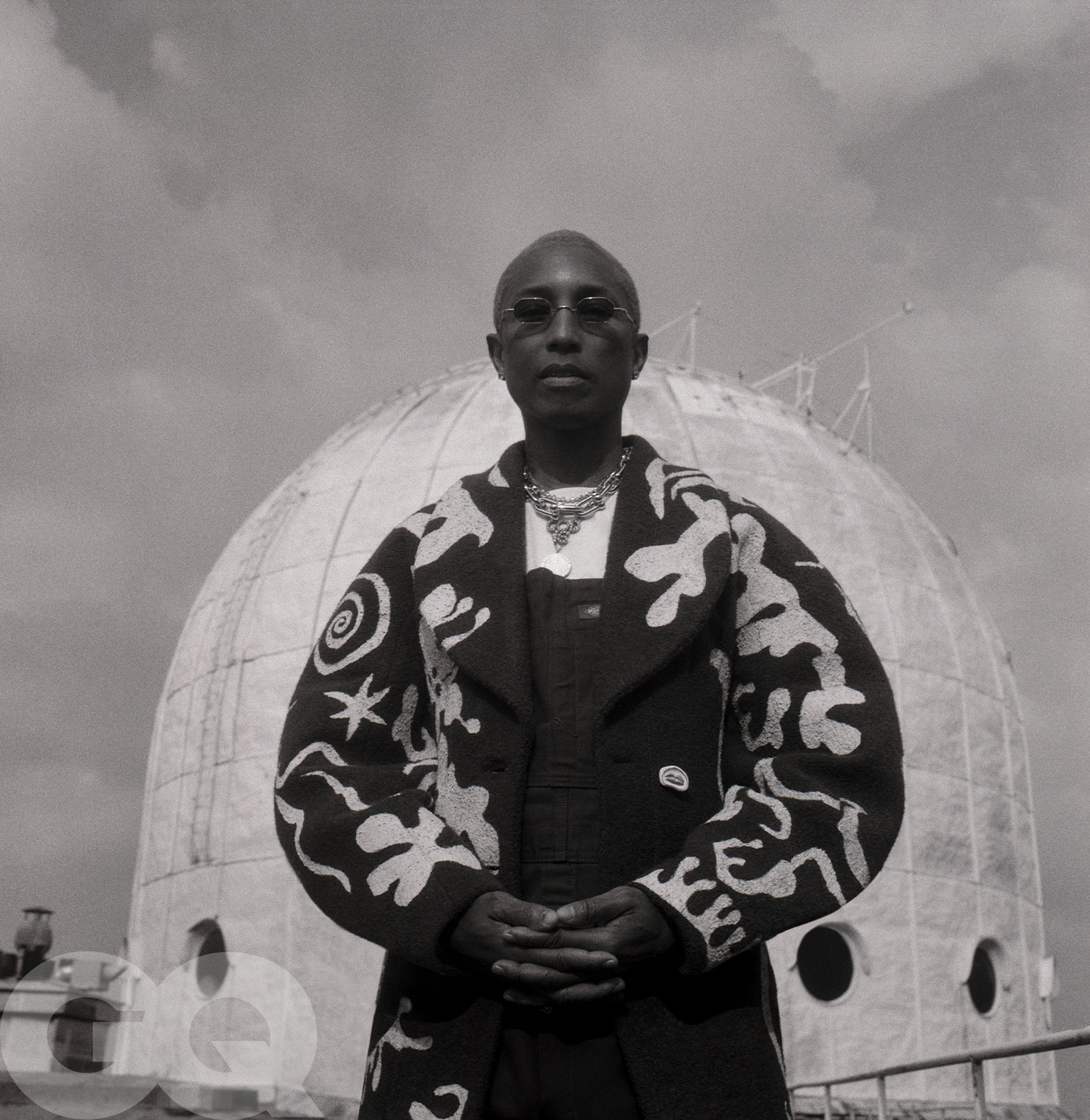

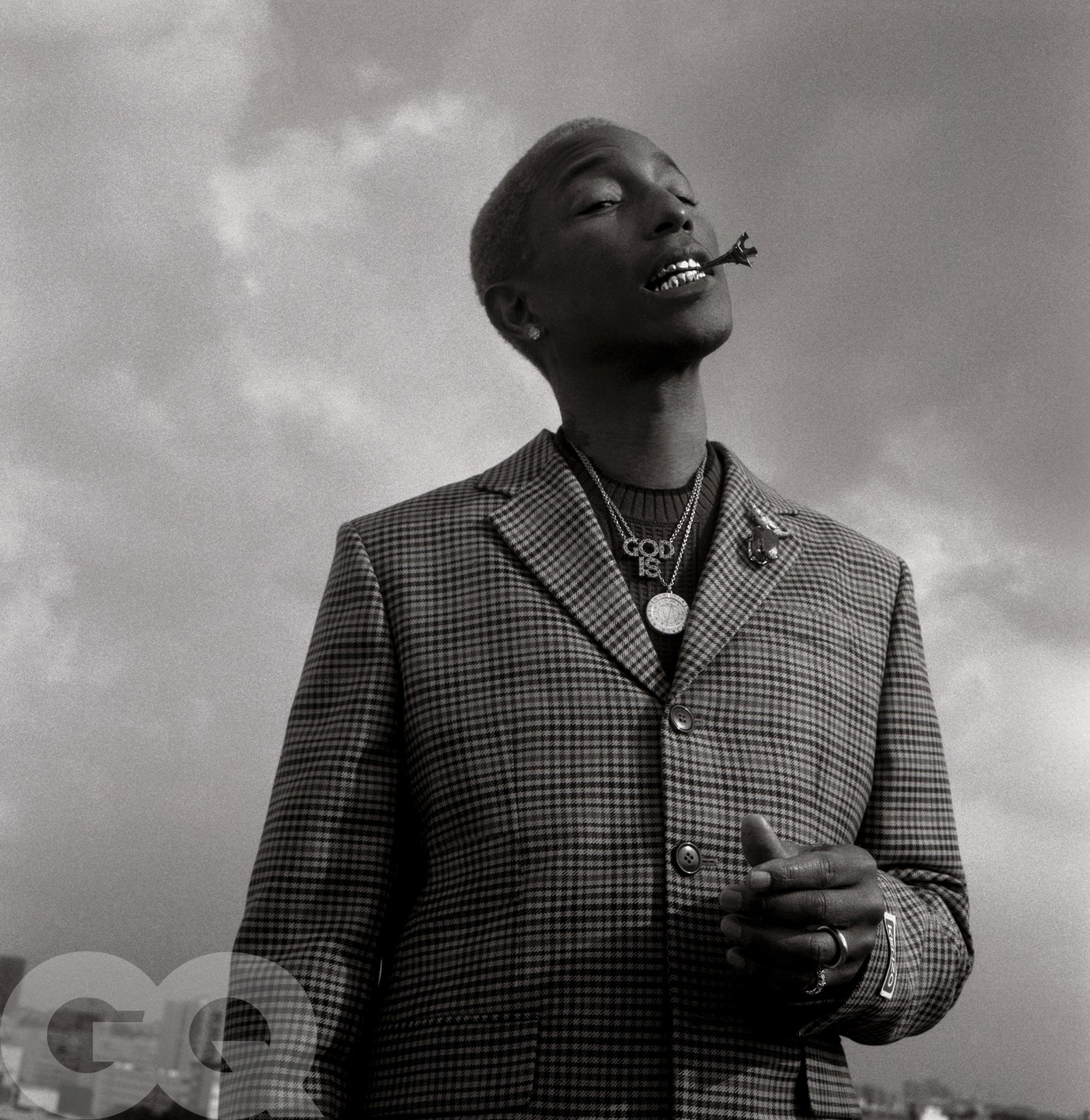

Pharrell was wearing what has become his signature look for this new era of his career—boot-cut LV jeans over LV snowboard-boot sneakers, a white tee from Nigo’s brand Human Made, and a Human Made baseball cap, with lots of gold-and-diamond chains on his neck and wrists, and an all-gold grill. The amount of gold and precious stones Pharrell wears seems to increase every time I see him. The jewelry is multiplying like gremlins. This feels notable.

For the past decade or so, Pharrell has been in something of a monastic sartorial era. He spent years as one of the most flamboyantly attired celebrities in the culture, then veered into a kind of ascetic simplicity that, he has said, represented the humility he wanted to project—his way of dealing with the tremendous success he found after back-to-back-to-back megahit songs in 2013 with “Blurred Lines,” “Get Lucky,” and “Happy.” At the end of 2022, he auctioned off part of his collection of Jacob & Co diamond pendants, the last relics of his legendary run as one of the greatest stunters—he was certainly the most innovative—in hip-hop in the early aughts. “His humble approach is him growing up,” Pusha T says. “Knowing the real importance of people, and how you treat people, and what you give off.” Even as Pusha T explains his friend’s personal-style metamorphosis, he bemoans it. “I would like to say, personally, that is not my stance. I want my homeboy to be as loud and obnoxious as I would ever want him to be.”

Pharrell and I sat on a squishy but expensive-feeling C-shaped bouclé couch in one corner of his studio. In the middle of the room there are several small conference tables; at each one a few members of Pharrell’s and LV’s creative teams are huddled, finalizing various aspects of the upcoming show.

For all the coming excitement of what he would soon reveal—big-time verging-on-revolutionary stuff that we were just days away from seeing at his show—Pharrell’s strategy for building the brand, he tells me, is surprisingly practical. He thinks about what he would like to buy or wear. He imagines himself shopping. “I look at myself like I’m the real customer,” he says between sips from a porcelain LV tumbler with a leather cozy and gold straw. “So I design for what it is that I want and what I’m going to need.”

With this approach, Pharrell packaged a presentation for Beccari and other top brass at LVMH when he first accepted the job. There was no real brief from the company, Pharrell says, although Beccari tells me that he encouraged Pharrell to consider the particularities of this moment—“the period post-COVID where people dress up a bit more, so to maybe instill the idea that Vuitton has also the mastery of tailoring.” Beccari says he was interested in Pharrell’s ideas for “a dandy man of sorts who is elegant, with a silhouette that is less oversized and fitted closer to the body.”

The crux of that presentation had nothing to do with Pharrell’s celebrity or the famous friends he’d bring along with him. It contained his notion of a complete men’s wardrobe, which he broke down into five categories: elegant tailoring, clothes designed for comfort, resortwear for vacations and staycations, sports clothes for both enthusiasts and practitioners, and a core collection of perennial basics. Then there would be the bags, the shoes, the sunglasses, the trunks, the toys, and all of the accoutrements of a modern luxury brand.

But Pharrell’s understanding of what it is that he and LV can offer is a little more conceptual than the standard hard and soft goods that brands make. “It’s not really about the items—even though we have a lot of items and we make new ones as well,” he says. “It’s about the idea. Trusting the brand that says that they understand what luxury is and how they can better suit your life.”

“It was spot-on and had a very clear direction,” says Beccari of the presentation. “Pharrell feels the responsibility of carrying a commercial weight”—something he undoubtedly understands not just based on his music track record, but doing things like starring on the TV show The Voice and launching a hotel in Miami Beach with the hospitality entrepreneur David Grutman. “We are here to deliver results,” says Beccari. “Together, it’s a hub of creativity and innovation—there are no limits to what we can do.”

The “no limits” thing is very real when it comes to Louis Vuitton. “When you get this appointment, what you get is an amazing team of 55 departments, 2,500 squadron,” Pharrell tells me. “Resources to do whatever it is that you envisage. You never really hear ‘No.’ ”

So far, Pharrell has done very little to decorate his studio space. When I visited, the furnishings were still being made and the place had a vaguely anonymous feel that he’ll no doubt correct. Except there’s one area that’s received his attention. He’s built a recording studio into the office. “I go back and forth between music and clothes,” he tells me. “Songs and shoes, accessories and harmonies. And it’s one fluid thing.”

And he’s productive as heck. When I was there in June, he told me he had finished three albums’ worth of music since arriving in Paris, all produced right there at LV.

Pusha T is one of the artists who’s joined Pharrell in his LV studio—an experience that’s given him new appreciation for his friend’s talents at getting things done. “He’s the true definition of a multitasker,” Pusha says. “The way that he can divert his focus and pivot at the drop of a dime is awesome. We’re in there working on music, a meeting comes up, it’s about color palettes or anything, he leaves the studio, walks right into the war room and gives it his all. Just the way that he can give direction, opinion, very well thought out at the drop of a dime.”

The area that Pharrell now uses to record music is the same spot where Virgil Abloh installed a DJ booth. It is a tragic reality that this huge opportunity for Pharrell has only been possible because of the untimely death of Abloh. “I always knew Virgil was special,” Pharrell tells me, adding that he’s maintained the connection to Abloh through Louis Vuitton, and some Abloh-designed pieces remain in the line. “It’s like we’re collaborating in spirit,” Pharrell says. And he has plans to continue to develop the house’s relationship to skateboarding, something that was initiated by Abloh.

Virgil Abloh once said that Pharrell had created a “new prototype” for Black artists. Of course, when Abloh arrived at LV, it was he who introduced a new culture to the house, and introduced luxury fashion to a new kind of creative direction—things that will now benefit Pharrell. Already, there is a strong feeling of continuity between the two of them. “After the untimely departure of Virgil Abloh, I don’t think I could have chosen a traditionally trained designer,” Beccari tells me. “I needed someone who was, again, connected to the arts, who could touch the hearts of people through music and fashion but also collaborations.”

Pharrell dedicated his first show to Abloh. He is not one to ever let you forget the significance of other artists and designers to his work and the culture around him. “I’ll always pay homage to him,” Pharrell says of Abloh.

The most obvious link between Pharrell and Abloh is the way both men seemed to have infinite reservoirs of energy and creativity for projects that spanned fashion and music and all kinds of other sectors. Abloh collaborated with Ikea and Mercedes-Benz and Nike, and he DJ’d clubs and festivals around the world. He was always on a jet, it seemed. Pharrell, similarly, will continue to juggle various design projects, businesses, charities, and, of course, music.

Lots of great artists are polymathic, but very few are able to be successful in more than one medium. I wonder if there is something about the unique relationship between music and fashion that puts Pharrell in a position to be one of the few—a favorite pair of jeans is like a favorite song, or the way a commercial hit has broad appeal and originality but triggers a familiar or nostalgic feeling in people. Albums do that. So do brands. A well-made bag, like a well-made song, lasts for decades and is as good as the day it came out. But even more powerful is the way both are forms of personal expression among their fans. Personalities are built around music and clothes. And Pharrell, since the very beginning, has had a supernatural understanding of that, and has consistently made things that unlock new dimensions of personality—he did it through music with the rap-rock group N.E.R.D., and he did it through fashion with Nigo and the radical global takeover of candy-colored streetwear. Along the way he introduced some major innovations to the hip-hop-fashion-history books: the yellow N.E.R.D. trucker hat, the gold-plated BlackBerry, the Jacob & Co pendants, the custom purple croc-skin Birkin bag.

Of course, in his new position, as he combines disciplines and invents new ways to reach bigger audiences, Pharrell appears poised to redefine the job of the creative director. I suggest to him that he could be shaping not merely where fashion is headed, but also where culture goes.

“I never looked at it that way,” he says. “I don’t zoom out as much, because if I zoom out, it might freak me out. I might see too much of what it really is like.”

So what did Pharrell do when he was given a job with no limits?

He started with his core creative crew—the stylist Matthew Henson, and Cynthia Lu, the designer behind the artisanal streetwear brand Cactus Plant Flea Market—and they set to work with the LV atelier on the collection. He tapped the American painter Henry Taylor for the only true collaboration in the line, and rendered Taylor’s loose, figurative paintings as embroideries and brooches embellishing suits. He identified the Speedy bag as the hero of the collection and campaign—specifically the Speedy 25, a mini duffel originally designed for Audrey Hepburn in 1965—and reimagined it as a Canal Street counterfeiter might, in primary colors but on leather so soft it seems to melt when you hold it in your arm. Then he developed his now-signature Damoflage print, a riff on LV’s iconic Damier—the checkerboard print we’ve all seen on Louis bags in brown and charcoal a million times—that Pharrell had manipulated to appear as pixelated graphics or blown-up versions of digital camouflage.

The collection is eclectic and elegant in the precise ways that Pharrell himself is. It plays with tropes—service-worker uniforms and American sports gear and boyish tailoring. And it’s full of unexpected concepts and silhouettes, as original and convincing as anything happening in fashion today, like chinos and rugby shirts made of leather, and sunglasses with one pearl-studded arm that goes straight over the top of the head like a mohawk.

The collection is massive, one of the largest menswear collections that Louis Vuitton has ever produced and shown. And it’s rangy, less like a cohesive statement about men’s fashion and more like a wild ride through all of the possibilities a maison with infinite resources can offer.

Days after we met at his studio, I took a boat ride with a couple thousand of my fashion-industry colleagues to the Pont Neuf, the oldest standing bridge across the Seine in Paris, to see Pharrell’s first fashion show. The location was the first indication that we were headed toward a historically significant event.

“They don’t let people do things on the bridge,” Pharrell had told me. Clearly, he had history in mind as well. “That’s crazy, bro. I’m this American, Black boy. What?”

It’s easy to suspect that Pharrell’s boss might have been helpful in securing the location. Almost 40 years after Bernard Arnault began assembling the pieces of LVMH, the luxury behemoth has reportedly made him Europe’s richest man. Of course, the looming corporate question that Pharrell’s arrival perhaps helps to answer is: What’s next? “LVMH wants to be in the business of culture,” the fashion journalist Lauren Sherman tells me. “Pharrell is a maker of culture.”

The expansive ambitions are already on display in Paris. From where I stood on the Pont Neuf for Pharrell’s show, I could see the LVMH headquarters and, across the street, the “LV Dream,” a Disney-style exhibition of the fashion house’s history, from 19th-century steamer trunks to Abloh’s greatest hits. Upstairs in the gift shop, visitors can pick up a new LV handbag or an LV chocolate bar. And the best place to stay to do it all is next door at LVMH’s Cheval Blanc hotel.

“They want to be anywhere that people are enjoying their life,” Sherman says of LVMH. “Any part of leisure.”

One important part of leisure is entertainment, which just happens to be something that Pharrell understands and can generate as well as anyone on earth. One attendee told me on the Pont Neuf that he felt like we were at Pharrell’s bar mitzvah. It was an initiation of sorts, but it felt more like an initiation for the fashion establishment than for Pharrell himself. In attendance was the holy trinity of famous women: Kim Kardashian, Rihanna, and Beyoncé. LeBron James was there wearing a pair of Millionaires shades. Rap dads Jay-Z and A$AP Rocky showed up. Plus a bunch of fashion faithful like Jared Leto, Zendaya, and Jaden Smith.

“There was no grass in sight,” Pharrell tells me with a smile after the show, referring to the historic assemblage of so many GOATs in one place.

Even before Rihanna arrived at the show incognito, her presence loomed. A week before, she’d appeared on a towering billboard on the river side of the Musée d’Orsay in a Louis Vuitton ad. Pharrell’s first face. A coup, even for him. “I walked in with that,” he tells me confidently. She was the face he wanted for his first campaign, so hers was the face he got.

The runway show had all the trappings of an epic spectacle. There was a live orchestra, then the Voices of Fire gospel choir led by his uncle Ezekiel, and a cascade of models wearing clothes that felt like they met the moment: vibrant, cool, opulent. It was not a tribute to Virginia so much as it was a tribute to love and joy and a kind of ecstatic, open-hearted optimism. LVERS, the show notes read, “is a state of mind: warmth, wellbeing, and welcome-ness.” This is Pharrell’s offering from Virginia to the world: abundant generosity of spirit, respect for humankind and ingenuity, love.

Not surprisingly, Pharrell ensured that music was an integral component of the night. The runway show featured a new Pharrell-produced song by Clipse, the beloved rap duo of brothers Pusha T and No Malice, who walked together in the show. For some rap fans, new Clipse music was as major a news-making moment as the new Speedy bags or his Damoflage innovation. Other designers have used the runway as a moment to debut new music—Ye debuted a whole album as part of a Yeezy-collection presentation. But the Yeezy audience was always made up of Ye fans. Pharrell is taking luxury clothes to a new audience, and taking the music from his hometown in Virginia to new listeners.

The grand finale was Jay-Z on a stage at the front of the runway performing a very generous melange of his hits, a few with Pharrell joining him. “This young man tonight did something extraordinary,” Jay yelled into the mic. “Pay homage to the great Skateboard P. Yes, sir. Congratulations, man. I’m so proud of you.”

Nigo put it best when I asked for his take on the Pont Neuf spectacular: “The first show was a completely different dimension,” he says. Nigo has been on his own righteous fashion crusade lately as the artistic director of Kenzo, a post to which he was appointed in 2021. The Japanese designer, who founded A Bathing Ape and almost single-handedly launched streetwear into the stratosphere, has been a close collaborator and friend to Pharrell since the two launched Billionaire Boys Club together in 2003. “Up to now, one of my roles has been the realization of Pharrell’s ideas,” Nigo says. “And I’ve always found his ideas very entertaining. His ideas are, in a word, cosmic.”

“Pharrell will never run out of ideas,” Nigo says. “I’m sure he will continue showing us new things. The fusion of music and fashion gives birth to a new culture for LV.”

Pharrell emerged at the end of the runway show wearing a Damoflage suit and diamond Tiffany & Co. sunglasses. He followed the many models who came out for their final turn on the catwalk, and in the middle of the bridge, Pharrell dropped to his knees and put up a prayer of gratitude. Then he embraced his wife and children, who sat in the front row with the Arnaults and the Carter-Knowleses. Finally, behind him came the rest of the men’s design team at Louis Vuitton who’d actually constructed the collection.

Two days later, back in his studio, Pharrell seemed giddy. I swear the jewelry had multiplied again. Even his yellow Speedy bag sprouted a new, diamond-encrusted gold strap. His show had, by then, already become one of the most-watched fashion shows in the history of YouTube and had reportedly been seen by more than 1 billion people worldwide. The mood was celebratory but still focused. No one appeared to be going on vacation just yet. Pharrell had spent the morning in the studio recording a new song. When I arrived, he had his laptop open and he showed me his screen. I asked him about that final moment on the runway, when he came out for his bow.

“From a vibration point of view, my heart was filled and my mind was light,” he says. “My energy just felt like I was floating just being out there saying thank you to everyone that came out.” Then he summed up the experience more directly: “This is the biggest thing that I’ve ever done and worked on in my life.”

Almost all of the press that followed was positive—with the exception of complaints about the traffic snarl in Paris caused by the bridge closure. “I personally think it is a fantastic debut, with a clear direction and a client’s point of view behind it,” Beccari tells me. “It clearly surpassed our expectations. And the outcome was amazing and never seen before. But above all, the collection is strong and received an outstanding welcome across the board.”

If Pharrell’s debut did anything, it primed us to expect more—to imagine that, in the future, we will look back at luxury fashion and see a clear delineation between the pre-Pharrell and the post-Pharrell eras. It felt like the beginning of something profound.

When I ask Pharrell about the future, and about the trajectory of the brand, and the vast aspirations LVMH has to bring culture and luxury together-—to cultivate a whole world of fans, only some of whom will become clients—he tells me that his own ambitions were broader than people might realize. “The house has aspirations to grow exponentially, but that growth is not just numbers,” he says. “Growth in taste, growth in setting the bar, growth in exceeding standards. The money follows that. We’re not going to just do things just to make money, or else we’ll just keep making the same belt buckles and shit. That’s not what I was brought here to do. I was brought here to shake the tree. That’s how you get the sweetest apples.”

Pusha T told me that, in this new era, a little of Pharrell’s flamboyant obnoxiousness might make a return. “It’s not even obnoxious,” he said. “It’s just the freedom of creativity.”

Sitting there with Pharrell, his golden grill catching the afternoon sun coming through the window, I ask what I should make of his new look—are we witnessing a return to stunting?

“The giant is waking up,” he says. Then I watch him make the decision to clarify himself: “I’m this little ant, but I have the spirit of a giant. And I think the giant is waking up.”

Noah Johnson is GQ’s global style director.

A version of this story originally appeared in the September 2023 issue with the title “Fashion Enters Its Pharrell Era”

PRODUCTION CREDITS:

Photographs by Fanny Latour-Lambert

Styled by Mobolaji Dawodu

Grooming by Johnny Castellanos

Sets by Jean-Hugues de Châtillon

Produced by Louis2 Paris

Location: L’Observatoire de Paris

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.