Originally a teen rapper as half of the duo Dr. Jeckyll & Mr. Hyde, New York City Andre Harrell started his career at Def Jam, but soon launched Uptown Records. Perhaps it was his sales background, but more than his contemporaries, Harrell injected lifestyle into his operations, propelling “ghetto-fabulous” from a mantra into a corporate blueprint. Uptown was a powerhouse during the ’80s and ’90s, launching the careers of Mary J. Blige, Jodeci, Al B. Sure!, Guy, Heavy D & the Boyz and not least, Combs, an intern-turned-A&R-whiz whom Harrell famously fired essentially for insubordination, leading to the formation of Bad Boy Records.

Harrell left Uptown to become president of Motown Records, expanded into film and television with “Strictly Business” (a launching pad for Halle Berry) and “New York Undercover,” and later reunited with Combs as president of Bad Boy and vice chairman of Revolt TV, where he worked until his death in 2020. His greatest success, though, was arguably in the artists and executives he nurtured.

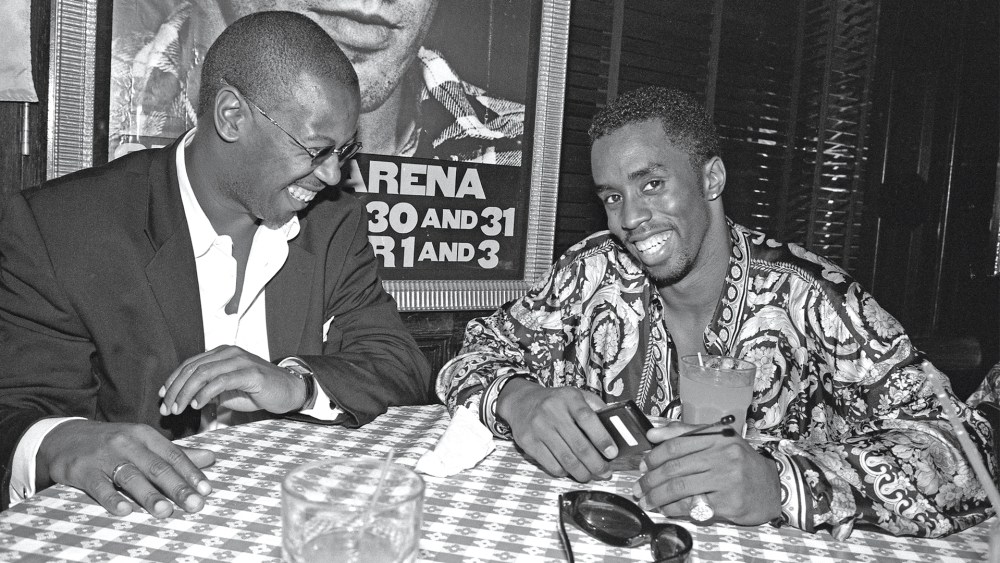

Below, as part of Variety‘s “50 Greatest Hip-Hop Executives of All Time” package, Sean “Diddy” Combs pays tribute to the man he calls his greatest mentor.

What do you think Andre brought to hip-hop?

Andre Harrell brought taste to hip-hop, and he brought a business acumen because of the reality of his background. He came up in the ‘hood, and tried to go to college and tried to work on the stock market, but he always had different aspirations. Early on, he was able to see hip-hop as a commodity, as a lifestyle. When people were making the music, Andre was dreaming big and preparing us for what hip-hop is today.

How do you think he brought taste to it?

The level of fashion, the level of boldness, the level of brashness, the level of art. A lot of people don’t realize that Andre worked for Def Jam first, and then when he started Uptown, he gave birth to me, to Mary J. Blige, gave much tutelage to Jay-Z and Timbaland and Swizz Beatz. He was our first mentor, and that really started to bring some structure to hip-hop, because it was being seen as another form of music that we wouldn’t really participate in from a business perspective. So when Russell [Simmons] and Rick [Rubin] started Def Jam, that really brought out the businessman in everyone. Russell and Andre took the art form into a way for us to get out, but also for us to be unapologetically Black.

Uptown not only had a great roster, but there was a level of class to it that we hadn’t really seen from a hip-hop label before.

Yeah — I mean, hopefully you’ve seen it from Bad Boy. (Laughter) At first it was about the rawness, but when he saw big stars like Michael Jackson or Luther Vandross or Aretha Franklin, he saw hip-hop, you know what I’m saying? He saw something bigger. He didn’t minimize it the way it was being minimized — he really saw it globally. He was able to show us how to use hip-hop to build a Black economy.

Do you remember when you first became aware of who he was?

I was a fan of his rap group, Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde. I saw them at Mount Vernon Memorial Field — it was one of the first rap concerts I went to — and I was so excited to see him because he was my favorite rapper.

Really?

Yeah! I went to an all-boys Catholic school in the Bronx and I had to wear a shirt and tie, and he was a rapper with a shirt and tie. I fell in love with his smile and his charisma. And when I started to pursue a career in the music industry, I tracked him down through Heavy D, just to meet him, and I told him I would work for free to get his knowledge, because nobody was teaching us the business. My girlfriend was at Howard University, she was in medical school; my friend was a lawyer — they both had internships in the summer. So I just tracked him down and took him to lunch, and I was his first intern. It was the greatest decision I ever made.

You must have talked a good game if he went to lunch with you.

Oh yeah. You know, I can make things make sense. (Laughter)

What was he like as a boss?

Aw, man! He was the boss that partied with you and he was the boss that nurtured you. He was your friend and your mentor. He could laugh and joke with you — you might be at the studio and then go out to a nightclub just to hear music, you know? He was the boss you loved to have.

I always used to lead with tough love, but from missing Andre and taking everything I learned from him, I’m leading more with love. He always led with love — well, he led with tough love when I messed up a Mary J. Blige concert, and on the day he fired me. But besides that, every day he led with love and he inspired people in a whole ‘nother way. He was a totally different person from a Clive Davis or Clarence Avant or Shep Gordon — he’s up there with those greats that helped to unify us. Maybe they didn’t make the most money, maybe they weren’t the richest, but they’re the reason why this industry exists.

It must have been a big transition going from working for Andre to working with Clive — I assume you guys party, but maybe not in the same way.

No — Clive is party man number one, but when you party with Clive, it’s maybe twice a year in St. Tropez and the Grammys. (Laughter) You partied with Andre every fucking day. I’m not talking about drinking — I’m talking about living life and laughing and being happy.

The story about him firing you is legendary — were there hard feelings?

No, no, no — I was just happy that he wasn’t mad at me because I felt like I’d let him down. It wasn’t hard feelings. I could tell in his eyes — he knew that I wouldn’t survive working under the corporate, oppressive thumb. When he fired me, he didn’t mean to hurt me — he just made me rich, because two days later I was a millionaire [via Diddy’s Bad Boy deal with Clive Davis’ Arista Records]. He didn’t leave me in pain for long — two days after I became a free agent I was independent, and he had a lot to do with that. And [a few years later], he came to work for me and ran my record company. So things got to be full circle.

Was it strange being his boss?

I never was his boss — that was the problem. I would ask him to do things, but I never could be his boss because of the level of respect that I had for him. I just let him do his thing and tried to stay out of his way. That’s really why I had him [in the company], to make sure that I could still have the things I lost from being around him when I got fired. I was still his intern! I was still a student of the game, and I knew I hadn’t learned everything. I definitely use that knowledge every day. He may not be here physically, but it was some Obi-Wan Kenobi type of teaching. I miss him so much.

Anything more you’d like to say?

He should be in the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, for real. He’s necessary. Hopefully this article will start that campaign to rightfully get him in that place, because he deserves it.