If beauty is in the eye of the beholder, what about ugliness? Just as beauty is unique to each person, so too is the ugly. It’s often considered the antithesis of beauty, visualized as existing on a spectrum with each quality at one end. Yet it’s the interplay between beauty and ugliness that’s fascinated philosophers since at least Ancient Greece. Without one, we cannot truly appreciate the other. Neuroscience has even found that the human brain uses the same neural circuitry to process that which we find delightful or disgusting, further revealing their connection.

The Great Make-Under

Oxford’s word of the year for 2022 was “goblin mode,” which describes a way of being that is lazy, self-indulgent, or slovenly, especially in a manner that rejects social norms. This followed “feral girl summer,” which called on spontaneity and a disregard for limitations. Instead of being a cause for concern, such loosening of standards comes as a welcome respite in an era of aesthetic restraint and perfection. The once-uncanny gloss of digital spaces like Instagram has made room for dressed-down visuals — as epitomized by TikTok and BeReal — even if they’re no less manufactured.

This recent wave marks a profound departure from gently ironic clothing in the 2010s — à la normcore’s dad sneakers, Teva sandals, and cargo pants — that transmogrified into luxury fashion extremes: gargantuan silhouettes, mismatched maximalism, unsettling color palettes, and a bevy of ugly shoes (the chunkier and more absurd, the better).

Demna Gvasalia’s appointment at Balenciaga brought ugly-transgressive style to the masses, too — speed dealer sunglasses, comically oversized outerwear, and “pantashoes.” Although anti-fashion, which refers to clothing antithetical to current trends, has older roots — designers such as Vivienne Westwood, Rei Kawakubo, Yohji Yamamoto, and the Antwerp Six were all pioneers — Balenciaga’s earnest fetishization of ugliness is one of the reasons it has become the de facto leader of ugly fashion.

The beauty industry followed suit, replacing “Instagram face” with gritty, imperfect makeup designed to look lived in, as per the return of “soft grunge” and “indie sleaze” aesthetics. It’s connected to the popularity of “no makeup, makeup” and the rise of crying selfies. Pushing the limits even further are distorted prosthetics like the overfilled lips and fake toothless gums as seen at BARRAGÁN’s Spring/Summer 2023 runway show (which dramatized the aftermath of a music festival and saw models emerge from a portable toilet) and by extreme drag artists such as Hungry and Charity Kase. It would be reductive to pin this plunge into grotesquerie on the fashion industry’s dire need for reinvention. Its obsession with newness and shock value are certainly partly responsible for the proliferation of deformity, yet ugliness’ hold on the imagination has oozed over into other areas of culture, too.

Bad Enough to Eat

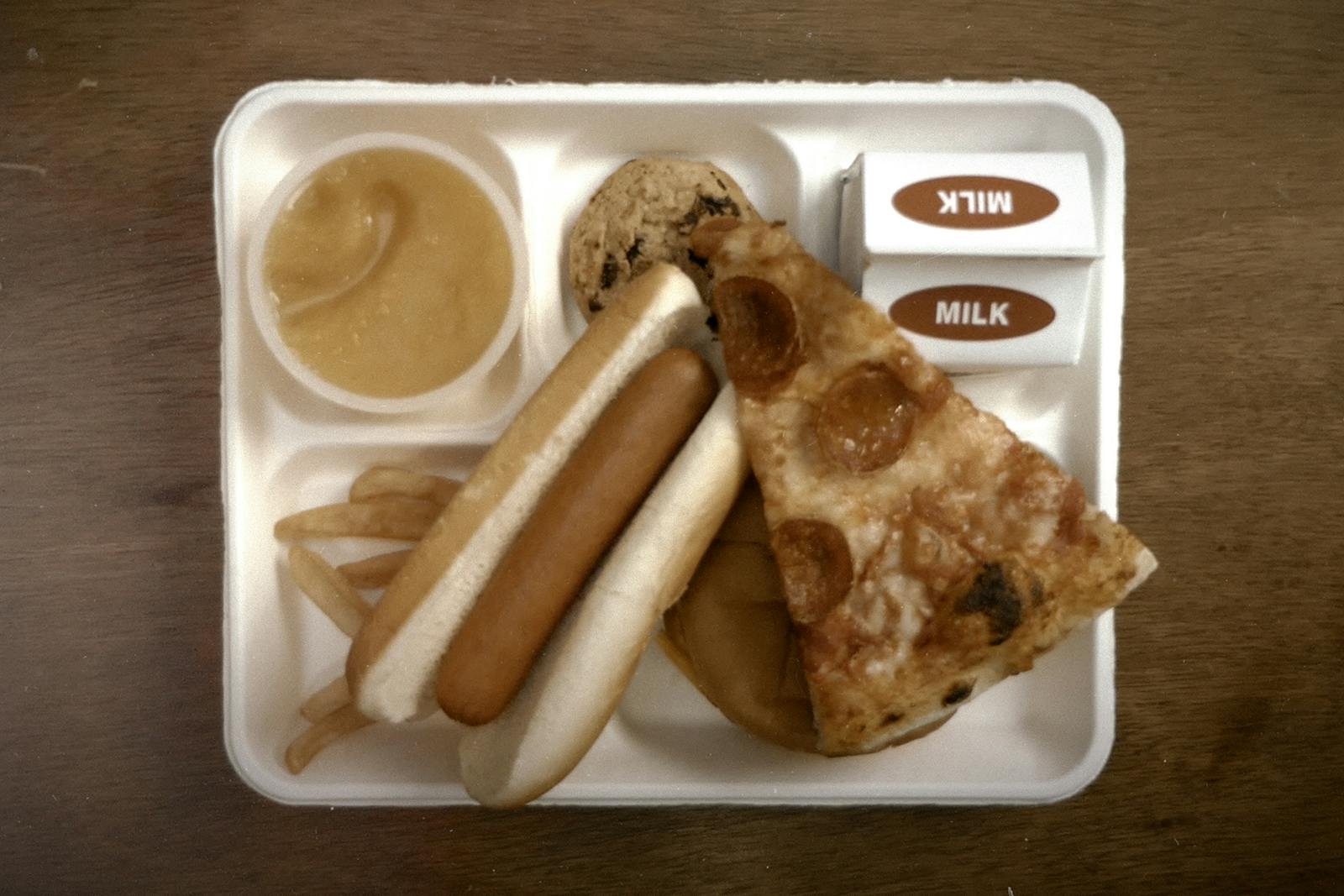

Somewhat surprisingly, we’ve seen ugliness emerge in food culture. The New York Times published a feature on “anarchist femme baking” in the first year of the pandemic, after intentionally offbeat cakes rose in popularity among amateur bakers. Feminist baking in general has gained traction in the last decade as a subversive take on domesticity. A continuation of absurd 1950s Jell-O creations, the recent wave of cakes comes in all shapes and sizes — from irregular forms to unsavory color schemes — and all share the common trait of ugliness. They’ve found a home on Instagram, where the bakers’ rejection of perfection subverts both expectations of gender and the “camera eats first” phenomenon — the trend of social media users taking mouthwatering food selfies before eating.

In Netflix’s Ugly Delicious, chef David Chang, of Momofuku fame, champions beloved food that didn’t have the esteem of haute cuisine nor the looks. The show makes a spectacle of food, much like punk and Dada art before it, by using the allure of ugliness to challenge deep-set notions about our world. This has been a hallmark of feminist punk and rock since it began in the 1990s. Through loud and aggressive behavior, ripped attire, and smeared makeup, the deglamorized appearance and performance of ugliness by women subverts their traditional role in society and reinterprets their bodies away from the male gaze. This has allowed other kinds of beauty and bodies to take up space.

Ugly-Beauty Standards

Today, the challenging of society’s beauty ideals is seen through the work of body morphing artists such as Fecal Matter, Michaela Stark, and Salvia, who deform their bodies to present alternative kinds of beauty. With contorted torsos, alien extremities, and feet shaped like heels, their work plays with the dichotomy of beauty and ugliness. But although they push boundaries, it’s no coincidence these popular artists generally fit within society’s attractive beauty standards before morphing themselves.

Lookism — more commonly known as “pretty privilege” when discussed from the opposite viewpoint — is discrimination based on physical appearance, and it affects those who fall short of social beauty norms. Coined in the 1970s by the fat acceptance movement in the United States, the term has been mostly limited to scholarly studies related to employment and culture, but lookism is starting to appear in mainstream media. In 2021, The New York Times asked “Why is it OK to be mean to the ugly?” as it investigated lookism and how prejudice against unattractive people “gets almost no attention and sparks little outrage.” In December 2022, Netflix released the anime series Lookism, based on a South Korean webtoon, which sees its protagonist navigate “a society that favors good looks” by switching between two bodies: one attractive, one ugly.

Although, as we’ve seen, ugliness can be weaponized as a form of political protest, it can also be formalized as a means to oppress. So-called “ugly laws” existed in the United States between the American Civil War and World War I, which barred people suffering from disfigurement or diseases seen as unsightly from going out in public. Such laws no longer exist, but there’s still a notable lack of protection laws against physical discrimination and, often, contempt for people who don’t fall within the confines of acceptable beauty standards.

When it comes to fashion, styles that lean into irony, like normcore’s average-looking clothing and the “weird girl aesthetic,” have been criticized for only working on those with skinny privilege, among other traits. The latter trend shuns classic sartorial rules for a whatever-goes approach, mixing clashing colors, naff prints, and quirky accessories all at once. While this is read as nonchalant on some — such as Bella Hadid, a poster girl for the trend — on those who aren’t seen as pulling it off, the wearer is punished with derision. This is embodied in the popular question, “Are they fashionable or just skinny?”

Similar privilege extends to celebrities, who also adopted ugly aesthetics beyond fashion in 2022. The dystopian bleached eyebrow trend was worn by everyone from Kim Kardashian and the Jenner sisters to Julia Fox, who declared “ugly is in” as she stole headlines with her transgressive looks. Doja Cat also swapped conventional prettiness for smudged makeup and eccentric body paint after she shaved off her hair and eyebrows.

Modernity’s Cult of Ugliness

Despite culture’s embrace of anti-aesthetics, it seems there are still caveats as to who is allowed to perform ugliness. This leaves us no better off than being caged in by crushing beauty ideals, but we can look to the 19th and 20th century’s “cult of ugliness” for how to truly democratize the unaesthetic. Coined by poet Ezra Pound, the term describes modernism’s embrace of ugliness in lieu of beauty as a response to the chaos and disorder of the time. Visual artists like Edvard Munch and Pablo Picasso began expressing the horrifying world around them through ugly form in their paintings, and the movement took off, changing art and aesthetics forever.

Considering our current global climate — a once-in-a-lifetime pandemic, unprecedented climate change, and the rise of conservatism — it makes sense that ugliness is experiencing a resurgence. Our traditional values and conventions have failed us and led society to seek out new perspectives. As per modernism’s cult of ugliness, by continuing to open up to a non-beautiful world through aesthetics, ugliness’ edifying qualities can ultimately offer us the greatest value.

Philosophical aesthetics contemplates the “paradox of ugliness” — the contradiction of enjoying something ugly while simultaneously finding it displeasing. This mixed response of positive and negative feelings is at the crux of difficult aesthetic experience — which contrasts with easy encounters, like the simple beauty of a sunset — and is precisely why ugliness continues to intrigue. Nuance like this allows us to better connect with other qualities of humanity, such as humor and sympathy, and shows us that ugliness, like beauty, is for all.

Stephen Bayley, design critic and author of Ugly: The Aesthetics of Everything, is firmly “pro-ugliness.” He explains that a wholly beautiful world would be incredibly dull. In the early 2010s, he predicted pro-ugliness as the next big thing, and here we are. So where do we go from here?

Dubbed the “master of ugly,” Miuccia Prada offered wise instruction back in 2013 — the same year Bayley predicted ugliness’ impending hold on society. “Ugly is attractive, ugly is exciting,” she said. “And why? Because ugly is human.”

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.