Have a topic you’d like us to delve into, a guest recommendation, or just want to say hi? Drop us a line at ontheissues@msmagazine.com.

Background Reading:

Transcript:

Michele Goodwin:

Welcome to On the Issues with Michele Goodwin at Ms. magazine. As you know, we are a show that reports, rebels, and we tell it just like it is. On this show, we center your concerns about rebuilding our nation and advancing the promise of equality. Join me as we tackle the most compelling issues of our times.

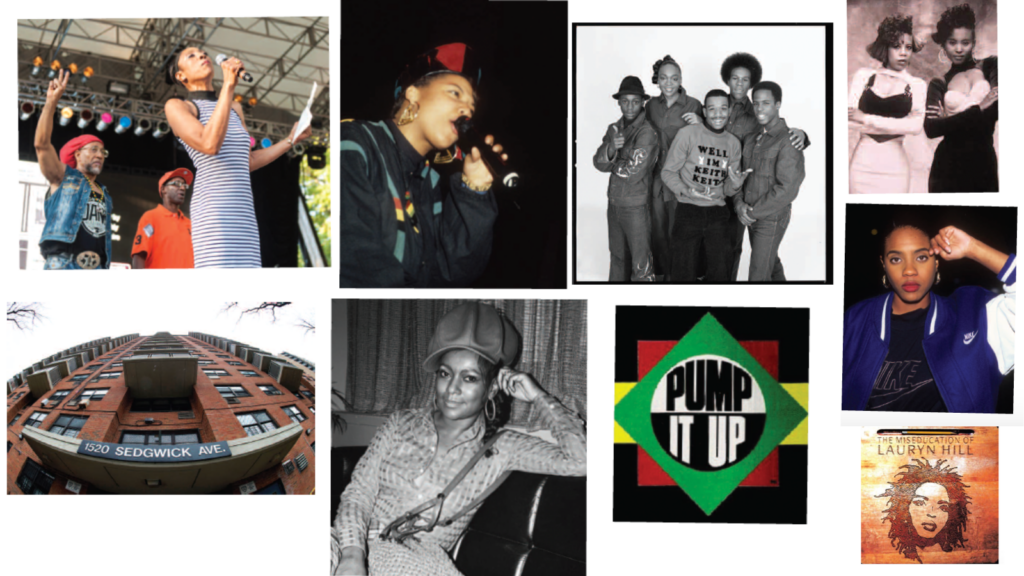

On our show, history matters. We examine the past, as we think about the future—and that’s certainly relevant for this episode as we recognize and celebrate the 50th-year anniversary of a music genre that has taken the world by storm, and that is hip-hop or rap music.

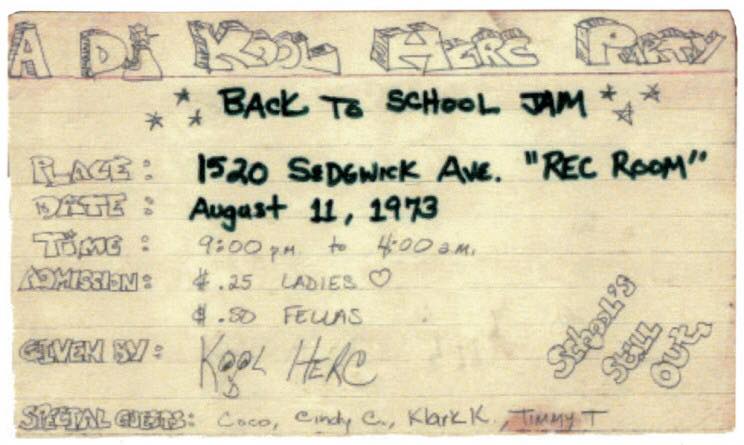

And for the rap aficionados, for those who are anthropologists of music—yes, you will be correct that the origins of hip-hop date back centuries, centuries, to African music and indigenous beats. But that said, many people point to a party that took place 50 years ago in the Bronx in a building on Sedgwick Avenue, and I know that’s going to mean something to a lot of our listeners, who happen to be from New York, or especially from the Bronx.

But from that first party on, women have played a central role in the genre taking off—that is to say that women have been pioneers in rap music, in hip-hop. Now that said, women have also experienced marginalization in the industry, and the industry as a whole, not just in rap and hip-hop, but certainly within the space. And there have been allegations of sexual assault and sexual abuse, misogyny, and at the same time, liberation, particularly with women using their own voices.

So, how do we unpack all of this and do it with an appreciation for the genre and yet, also, deep respect for women and people who want to lift women up who are part of the industry? And so, in this episode, we are looking to bridge many gaps and to talk through these nuanced issues.

And so, I’m so pleased to be joined by two very special guests, as we think about and celebrate and recognize the 50th birthday of hip-hop and rap music, as we grapple with questions such as the following brought to us by one of our listeners: Women love hip-hop, but has hip-hop always loved women back?

In this episode, I’m joined by Drew Dixon. Drew is featured, in fact, the focus of HBO’s 2020 documentary, On the Record, which explores the allegations of sexual harassment and abuse in the hip-hop industry, specifically targeted at hip-hop mogul, Russell Simmons.

Drew is a music producer, television producer, writer, and activist. She formerly worked as vice president of A&R at Arista Records. Amongst those that she’s worked with include Whitney Houston, Aretha Franklin, Mary J. Blige, and many others.

I’m also joined by one of our stalwarts at Ms. magazine. That is Janell Hobson. She’s a professor of women, gender, and sexuality studies at the University of Albany, and please, check out her writing on this featured in our print issue of Ms. magazine.

I want to welcome both of them to the show as we think about what this 50th-year anniversary means. All right, sit back, take a listen.

It’s such a pleasure to be on with both of you, especially as we think about the history of music, specifically the history of hip-hop, rap music. And Janell, I want to start with you. I thank you for the important work that you do at the intersection of gender and sexuality studies. It’s been so critical and such an important and valuable role that you’ve played with us at Ms. magazine. And so, I want to ask you, why is it so important to tell the feminist history of hip-hop, and in this moment in particular?

Janell Hobson:

I thought, with all of the celebrations that are happening this year, I had an inkling that somehow women were going to be marginalized. Fortunately, I did see that we were included in some of the important tributes.

So, with the Grammy Awards, they did that special tribute at the Grammy Awards earlier this year, and they included Salt-N-Pepa, they included Queen Latifah, Missy Elliott, you know, the big ones who had a tremendous impact on the genre. But there were other women who were missing and that tends to be the case, unfortunately.

So, we didn’t see Roxanne Shanté, we didn’t see J.J. Fad, but I did see Queen Latifah, Monie Love, you know, they definitely stepped in to make sure that women were included.

I thought that also took place with the Fight the Power documentary that aired on PBS. That one was the project that Chuck D from Public Enemy oversaw, and that did a pretty good representation of gender issues. So, I was glad to see it, but I definitely thought, at least with regards to doing my Ms. article, to make sure that we did have a feminist perspective, because it’s one thing to include women, it’s another thing to also include a kind of feminist critique about the culture so that we can celebrate, as well as hold the culture into account as well.

Women love hip-hop, but has hip-hop always loved women back?

Michele Goodwin

Michele Goodwin:

Well, Drew, let me pull you in to that conversation on that point because you’re as music producer, television producer. There’s been so much that you’ve done, and you’ve been right in the thick of the rise of hip-hop, a space that has been complicated, beautiful, but complicated, really complicated, especially when thinking about matters through the lens of women, either women trying to make a rise, or women being the subjects of some pretty violent lyrics and things like that.

Drew Dixon:

That’s right. Yeah. Well, you know, I love hip-hop. I always will love hip-hop. I think hip-hop captures the resilience, the defiance, the creativity of Black people in this country, and I’m really grateful to see hip-hop celebrated at the 50-year milestone mark, really exciting. But I do think the celebration of hip-hop reflects that culture of hip-hop, which has been misogynistic the whole entire time. I think, sadly, it’s become more misogynistic over time.

I think that at the beginning, when hip-hop was sort of rebellious and it was anybody’s game, and it was a jump-all on anyone’s microphone, you had artists like Mercedes Ladies, Sherri Hines kind of right there in the thick of it with the guys, but she was derailed. So many of us were derailed.

Sylvia Robinson founded Sugar Hill Records, but I think that over time the patriarchy, rape culture, the misogynoir that is even worse than just regular misogyny because it’s for Black women who are doubly bound and undermined by both sexes and races, and the way Black women have never been safe in this country is reflected in the music. It’s reflected in the business. It’s reflected in the way checks get cut, opportunities get handed out, and recognition gets given.

And so, the 50th anniversary of hip-hop reflects that, and I think it’s an opportunity for us to do exactly what you are doing now and what Janell is doing through her work, which is to make sure that we center the voices, the perspective, and the contributions of women and hip-hop—one for the sake of getting it right for the last 50 years, but even more importantly, to make sure that the next 50 years is more just and more equitable and hopefully, more uplifting.

Michele Goodwin:

So, Drew, I’m going to follow up with you on that. So, you know, what do you attribute to, what have been some of these internal hurdles within the space of hip-hop for women?

Drew Dixon:

Well, you know, hip-hop is part of American culture, and America was an apartheid state long before it was a democracy. America is racist at its core, legally, socially, economically, in every possible way, that’s baked into the American cake or the American pie, whatever you want to call it, and hip-hop reflects that.

And so, you know, the lyrics, that I didn’t even really process when I was a young woman, that are so problematic and objectified and violent in some cases, and dismissive of the humanity of Black women and girls, the colorism, all of it. It’s not hip-hop’s invention, it’s not hip-hop’s fault, but hip-hop became this venue where all of that was represented.

And then, I believe, as I look back on my career and I look back on the people who became the gatekeepers of this culture, amplified and in some ways almost cartoonized, to make rebellious Black culture palatable by making it also self-destructive and nihilistic.

So, we can say “Fight the Power” while we’re shooting ourselves in the foot and …

Michele Goodwin:

Janell Hobson:

Literally, literally that part.

Michele Goodwin:

Girl, literally, literally.

Janell Hobson:

Right?

Michele Goodwin:

Well, okay. I feel like a pause on that one, right? Literally in the foot.

Drew Dixon:

Oh, my God, that part. And I think that a lot of people became very rich feeding mainstream America a violent rock-and-roll version of Black rebellion that was safe because it was rebellious and self-destructive. Rebellious, but absolutely undermining the fabric of our own community, our own families, our own relationships, and it kind of got by us because it was a rejection in some ways of what now is a quite ironic Bill Cosby model of respectability, which I think was a needed pushback.

But now it’s kind of ironic to me that the person who was a champion of Black respectability was a serial predator, and the person who was the king of Black rap rebellion was a serial predator, and they both became incredibly successful, and it’s deep. It’s very deep.

Michele Goodwin:

You know, that is so deep. You have dropped rubies, diamonds, pearls all over, just sprinkling the red carpet now just full with that. You’re right. So, Janell, how do we understand that? I mean you write about these matters from an academic perspective, as well as part of opinion editorials and commentary. So, maybe let’s pull back a moment from hip-hop to actually invest in what Drew has just shared with us about the culture of an apartheid state in the United States.

I mean let’s be clear. That’s not inflammatory, that’s just real, you know? When individuals are kidnapped from their home countries where they have families, where they have their own lives, and they’re kidnapped and they’re brought into a system where they are labor-trafficked, and then where the girls and women are sex-trafficked for the profits of others, and that is protected by law, by federal and state laws, that’s what Drew was speaking to. This is not imaginary, right? That’s real.

But if that’s the backdrop, then it seems that before we even get to the question of hip-hop, there are certain things that we must contend with in terms of how this nation addresses women, as a general matter, and women of color, specifically, and in a really deep way, Black women.

We, as women have always been there. We’ve always provided the space. We’ve provided the kind of communal safe spaces for our partying, for our cultures, and yet, we always get dismissed or marginalized.

Janell Hobson

Janell Hobson:

Those are really good questions. And also, I’m still reeling from the gems, the rubies that Drew dropped on us.

I think back to where we are now because this is a milestone moment in terms of 2023, and it’s dawned on me that not only are we dealing with the 50th anniversary of hip-hop, but we’re also dealing with the 50th anniversary of Roe v. Wade that just, that got overturned last year.

So, it’s interesting all of that happened in the first year, this birth, this emergent movement of both, of cultural music, as well as a moment in terms of feminist movement, in terms of Black liberation, as well as a Black women’s movement.

And so, it’s probably not a coincidence that we are here, where we are now, because I do believe those things are related, they’re connected. This idea that we can move forward, but not really move forward in terms of women’s rights, the erosion of our reproductive rights, our reproductive justice, and how might that be linked to what was going on in hip-hop?

I mean hip-hop was a response to so many of the failures of the state back in the day, both in terms of a kind of post-civil rights moment of not being able to achieve racial equality, still pushing and pushing for feminists and gender liberation, and here we are in this moment where we are still contending with that.

So, it’s not a surprise to me that hip-hop would be a mirror so much, you know, reflecting on many of these particular critical issues around race, class, and gender, and yet at the same time, not necessarily using a mirror to correct, but also exacerbate, and that also happened.

I think there are moments when you have hip-hop being used as a kind of political resistance, but oftentimes I think there is more political assimilation. We definitely see that with the rise of the billionaire class. I think it says something that this particular genre of Black music is the particular genre that enabled our first set of multimillionaires and billionaires, whereas in the other genres: jazz, [blues] …

Michele Goodwin:

You know, that is fascinating, right?

Especially with the profound artistry within those other spaces as well, the musicality within those spaces, the learnedness, the studying that was a part of these other spaces. And so, all right, we’re getting deeper and deeper. Shovels are out with the level of depth that’s coming into this conversation.

Drew, I want to pick up on your career because you’ve been at the forefront to this conversation, not just a sort of who becomes the subjects of the music and the violence that is associated with that, but there are careers that are at stake. And so, you, as a career professional within this space, you have come forward.

You know, you’ve been a figure in the industry since the 90s, and in so many ways you’ve seen the best and also the worst of all of it. And you have been outspoken about what it means in terms of the sexual violence that women have experienced as part of the industry, and you’ve also shared publicly about what you have experienced.

And so, I think our audience would appreciate hearing about that, too, Drew. If you could share with us about that aspect of an industry, which in some ways one could say, you know, compared to Harvey Weinstein, right, we’ve seen it across so many different spaces, unfortunately, the violence.

Hip-hop was a liberation movement with a microphone at its core.

Drew Dixon

Drew Dixon:

Right. Yeah. Well, you know, I came to New York in 1992. I was 21 years old and I wanted to make rap records. I grew up in a family that was political Black PC. My mother was the first Black female mayor of a major city in-between Marion Barry, which is relevant to people my age. It may not be relevant to others.

But I grew up sort of very clear that my mission was to lift us up in whatever way I felt like I could do that the best, and I was always a music-head. So, hip-hop really appealed to me because it was something that I loved, but also it felt like it was a liberation kind of movement with a microphone at its core.

And so, I came to New York and started answering phones, very naïve and wide-eyed about this mission and didn’t really fully understand just how entrenched the misogyny of it was. I thought that if I could prove that I was good at what I did, if I proved that I had ears, as they say, and could make a hit record that the sexualization that I was experiencing would go away because it would be clear that I was going to add value, and that was not really my sort of role or purpose, and that’s not what happened to me.

I was at Def Jams, my dream job, after three jobs answering phones, and one job doing music publishing where I signed Nas to a publishing deal before Illmatic and Erik Sermon to a publishing deal. I had the idea for the Mary J. Blige, Method Man to what “You’re All I Need to Get By” and…

Michele Goodwin:

Oh, that is huge.

Drew Dixon:

Oh, yeah.

Michele Goodwin:

…huge. But did you get credit, Drew?

Drew Dixon:

I did not get credit.

Michele Goodwin:

I know you’re going to say no.

Drew Dixon:

I didn’t.

Michele Goodwin:

I need to ask.

Drew Dixon:

And not only, I mean when I tell you it wouldn’t exist if it weren’t for me, it wouldn’t exist if it weren’t for me. I was typing the label, the album credits, and I heard the interlude, “Shorty, I’m there for you anytime you need me, you know, for real, girl, For real girl, it’s me in your world, believe me,” and it was just an interlude, and I was like, I can’t stop listening to that, that’s beautiful, that’s love. That’s love in the vocabulary of hip-hop, right?

And that is so important. And I believe women, young women like me who love hip-hop need to hear that because it’s not about sex. It’s not … it’s love. It’s partnership, right? And I pushed and pushed and pushed and pushed until it was finally made into a record.

I called Puffy. We got Mary. It’s a long story that I’ve told in other places, but I fought tooth-and-nail every step of the way for that to exist, and it never occurred to me in a million years that it would come out and my name would be nowhere. Not an A&R credit, not a producer credit, which I should have because it was my idea.

Michele Goodwin:

And all of that matters. That matters…

Drew Dixon:

It does matter.

Michele Goodwin:

I mean, okay, so we’re going to get to the Russell Simmons stuff. But on this, it matters when you have pushed, when you have identified, when it’s been your creative energy behind a matter, but you don’t get those credits. What does that mean, Drew, just so that our listeners understand what that’s all about, because they may see like, look, like people know your name, you’re famous, like how do …

Drew Dixon:

Yeah, they didn’t.

Michele Goodwin:

Was that mean or they don’t know?

Drew Dixon:

… for that record until the MeToo movement and until I told that story in the documentary. I would listen to that record in Urban Outfitters with my kids, in a dentist’s office with my kids, in a cab by myself and just want to cry because I’m not even … I think I’m in the Wiki now. I wasn’t even in the Wiki until after On the Record, until after MeToo. I didn’t get a producer credit. It won a Grammy. I didn’t get the Grammy. I can’t call myself a Grammy-winning producer, even though I am, right? I didn’t get the check. I didn’t get the royalty.

And not only that, I didn’t get the wind at my back that a hit like that gives you and helps you to level up in your career. I did however then put together a soundtrack for a documentary about hip-hop called The Show, and in that case, I typed the credits. I picked every song. I like helped negotiate every deal. I sequenced it. I did it all. I typed it up. I called all the artists to get the songs, I was like, “Did you overcut your album, send me anything extra,” and that’s how I got like a Tupac song and you know, like a Bone Thugs song.

And I wanted to represent hip-hop regionally and genre-wise. And I typed the credits, and that’s why I’m an executive producer of Russell Simmons because I typed it, I was. I didn’t put myself first and I was like, maybe that’s going to like cause a problem. I made myself second, but like l typed it because I was like, I can’t let this happen again, and that was the number one R&B album in the country the night that Russell Simmons asked me to come upstairs to his apartment and pick up a CD.

I thought I’d be in there for five minutes. He wasn’t even in the room when I was opening the CD player and trying to find the CD that he vaguely described to me on the shelf next to his CD player. I now realize in 2017 that there was probably never a CD, and I was looking for the CD when he showed up behind me on my left side, naked wearing a condom and tackled me, and I fought, and I screamed, and I growled, and I scratched, and I kicked, and I said no. I begged and I pleaded, and he raped me, silently.

I had the number one album in the country, the number one R&B album in the country with him that night. And I quit my job.

Michele Goodwin:

I am so sorry, Drew.

Drew Dixon:

Yeah.

Michele Goodwin:

Okay, yeah.

Drew Dixon:

Quit my job, was going to quit the industry, but because I had his album, which was like hanging in there on the top five, top seven, top ten, whatever, because of that I was able to get interviews at other companies. And I was going to quit my job, but then I was like, Wait, I have Stanford student loans to still pay, I have rent to pay. I can’t actually just quit my job. I actually have bills that I have.

I had a Macy’s credit card I opened to buy sheets. I had to pay that, you know? And so, I got a job at Arista Records and I reported directly to Clive Davis, and I actually dusted myself off and came back and actually, called all of my hip-hop friends, like Wyclef, and Lauryn Hill, and Montell Jordan, and Q-Tip, and Brand Nubian, and I made records there.

Wyclef gave me “Maria Maria” for Carlos Santana. Wyclef gave me “My Love is Your Love” for Whitney Houston. Lauryn Hill gave me “A Rose is Still a Rose” for Aretha Franklin. Montell Jordan gave me “Nobody’s Supposed to Be Here” for Deborah Cox.

So, I called my hip-hop friends and we made hits in the building on major stars. And…

Michele Goodwin:

So, Drew, if I can, so, it … well, one, I want to acknowledge what we’ve just heard and the pain of that. On this show, women have told their stories in ways that sometimes have just surprised me, things that I didn’t even know, and we have very good research and whatnot. And you’ve just shared a profound story, one that our listeners can relate to, one that other people who have been guests on our show can relate to.

And what you’ve also shown and demonstrated in so many ways is just this way in which we sort of forced resilience, resilience that happens. Like, so, you tell the story about a great high, then a tragic, horrific, violent low.

Drew Dixon:

Yeah.

Michele Goodwin:

And then, you tell that story that sounds like our grandmothers, like, girl, why are you leaving? You shouldn’t be leaving. You didn’t do anything wrong. Like, that’s the story that we hear.

And then, this sort of taking of what are some acidic stuff and making lemon meringues, lemon pies, lemonade, lemon juice, lemon jams, all of that. You did all of that, Drew, in just like the three, four minutes, and you just shared with us.

Drew Dixon:

Yeah. Well, I, you know, I am, like all of us I am the descendant of enslaved people, and so what do we do? I mean what are you going to do? You got to keep going, and I’m going to keep going. I’m going to keep going to the light, and I’m going to keep … you know, what breaks my heart as, I look back at 50 years of hip-hop, is that I was ultimately pushed out of the industry by the person I worked for at Arista after Clive Davis. And I tried to sign Kanye, I tried to sign John Legend, I was not able to.

Michele Goodwin:

What happened?

Drew Dixon:

You know, I … it’s painful to revisit these stories. But Clive Davis was replaced by someone whose name I don’t even feel like mentioning, and I tried to sign Kanye West and John Legend. And I was not interested in the kind of relationship that he wanted to have with me, and therefore I was not able to sign those artists.

And that’s when I gave up and went to Harvard Business School. I was very blessed. I was like, I’m going to just try to make it look like a graceful exit, even though I was devastated, and I actually had the thought, Maybe if I get an MBA from Harvard, that’s like kind of like being a white man. That’s like the closest degree I could think of to make me like a white man. And it turns out it didn’t work: still a Black woman in America.

Came back. I ran John Legend’s label, and I actually called Kanye West and asked him to on “American Boy,” so also involved yet again in making another hit record, iconic record.

But as a woman, it’s so hard to even be in the room, it’s so hard to even get the shot, that you don’t then have the leverage to fight for the credit, for the point, the royalty.

And so, I’ve helped to make many Grammy-winning records. “Maria Maria,” I found. “My Love Is Your Love” I don’t know if that won a Grammy, but I know “A Rose Is Still a Rose” and “My Love Is Your Love” were Grammy-nominated. I have an A&R credit on “It’s Not Right But It’s Okay.” “American Boy” won a Grammy. I don’t have a producer credit on that.

I was so grateful to be kind of climbing my way back in the industry after getting pushed out that I didn’t…and I was at the time literally nursing my son. I had a 2-year-old daughter. While I was helping Estelle to make that album that I didn’t fight as hard as I probably should have for the producer credit on “American Boy,” and so I don’t have that either, and it’s another record I can’t point to and say I’m a Grammy-winning producer.

And so, the systemic disadvantage, the systemic disadvantage we face all the time as Black women makes every single aspect of every single thing, we do harder. And so, even if we’re able to do the thing, we don’t necessarily get the credit for doing the thing, or the check for doing the thing, or the, just the leverage that comes from doing the thing, and it’s devastating to me personally,

I’m 52 years old, I really have very little to show for my contribution to hip-hop and music, other than the fact that I’m now back because of MeToo and can talk about it freely. So, I couldn’t even talk about it for 20 years. I couldn’t even explain why I disappeared for 20 years, and that was like a death.

But I also think the cost is when people get pushed out, people like me—I’m not the only one, I’m sure, I’m certainly not, but when you push out women and you push out the women who don’t want to, or not even who don’t want to, who aren’t coerced into accommodating your misogynist, objectified, sexualized position for them, you’re pushing out a voice at the table that makes “A Rose Is Still a Rose.”

The systemic disadvantage we face all the time as Black women makes every single aspect of every single thing, we do harder.

Drew Dixon

Michele Goodwin:

Oh, sure, the pushing out the…

Drew Dixon:

And it makes the duet with Mary.

Michele Goodwin:

Yeah.

Drew Dixon:

You’re pushing out that light that’s trying to hold space for Black women and Black people to be represented with love…

Michele Goodwin:

Drew, I mean and…

Drew Dixon:

…and dignity.

Michele Goodwin:

…important, Drew, but it is also you’re pushing out success. I mean we’ve seen this. I mean you’ve been at Harvard Business School so that you know the corporate, all of the studies tell us, right, overwhelmingly the empirical evidence is from numerous studies that the more diverse, female-diverse, that a corporation is they maximize, they make more profit, their goods are better, they ship more, like all of that, right? You know, do women bring creativity to the space that helps to maximize in all of the business ways for companies around the world?

Janell, I want to turn to you because this says so much. The flavor of this conversation says a lot and it raises questions where people say, well, you know, well, if it’s so bad, why are women staying? Of course, then when women take a stand and say, okay, I’m not going to stay for this and folks say, well, women should just be stronger. Clearly, they just can’t keep up with the boys.

What’s the response to that for folks who are struggling through this, see career paths that they’d love to stay on, but are experiencing exactly what Drew has gone through?

Janell Hobson:

Yes, such an important question. And I’m so glad that, Drew, that you’re here to share your story for this podcast because it’s integral to why I wanted to do my article for Ms. in the first place.

So, in “Turning 50,” I was very strategic in opening up with a quote from Dee Barnes, who is another Black woman in hip-hop who almost got erased, but she pushed back, just like Drew’s pushing back, so that we can remember their place, their space in the culture.

And she reminded me in our interview that, you know, were it not for DJ Kool Herc’s sister, Cindy Campbell, who hosted a party, we wouldn’t have had this moment for hip-hop to even be invented. So, we, as women have always been there. We’ve always provided the space. We’ve provided the kind of communal safe spaces for our partying, for our cultures, and yet, we always get dismissed or marginalized.

We get, we kind of like pushed out, but we’re the ones who are making sure that we have the love, we have the communal love, we have the space for that.

It is so important, I think, in bringing feminist history into hip-hop because it’s so easy to just focus on the kind of masculine bravado that is, you know, the kind of posturing that defines the genre—whereas there are so many other elements to various artists who contribute to creating this culture, which started as underground and now it’s global, and so we’re dealing with that.

And just hearing the kind of experiences how Drew Dixon, who’s, you were a genius, obviously, and we are blessed with y our genius in being able to make space for the kind of records that came out through Def Jam and Arista with the examples that you cited.

And unfortunately, you got pushed out of … for the most misogynistic of reasons in terms of rape culture, and we need to be able to break the silence about it.

It’s interesting to me that even though we’ve had this MeToo moment with Hollywood and Harvey Weinstein, and even Bill Cosby and R. Kelly, I don’t think we’ve even scratched the surface in terms of hip-hop. The documentary, On the Record, just gets to talking about the issues with Russell Simmons, but we haven’t really gone, we haven’t delved further.

And I think the more we’re able to amplify the voices of those who’ve been marginalized in the community, we will start to get those stores as long as we’re willing to listen. And that’s why it was important to me to actually write this piece for Ms. And to actually, to center women in this particular 50th anniversary celebration.

To me, it’s a celebration, as well as a critique, with love.

This is what Tricia Rose, one of our hip-hop studies pioneers, said in her interview with me, which is we have to come with the critical love, to be able to do affirmative entrance formative love that we are going to hold the culture accountable, even when we love hip-hop and celebrate it and dance to it and whatnot and still have to call out the misogynoir, or we still have to call out the violence.

We still have to show up for, you know, women like Megan Thee Stallion, you know, when she gets shot in the foot, right, and to call it out, to always do, to do that work, and to be able to provide a microphone, and to not get discouraged when there are enough people in the communities are like, ‘You know, don’t air dirty laundry.’ It’s like …

Michele Goodwin:

We’re so far beyond, right? We need to be far beyond that. I mean, certainly, we can see that the people who suffer when we hear, ‘Don’t air our dirty laundry,’ always happen to be women and girls.

Janell Hobson:

Yes.

Michele Goodwin:

Right? Don’t tell when you were sexually or physically abused. Don’t tell when you’ve been shamed, you know. Don’t tell when you’ve been threatened, all of those things. And it is a time for liberation.

So, we are five years out from the most recent iteration of MeToo. Tarana Burke had named that years before, but it got some momentum five years ago. And so, I’m wondering as we look forward, as we begin to wrap up the show, and really, I’d have multiple shows with the two of you, truly.

What does the future of feminist hip-hop look like, or women in hip-hop? What would you say, Drew?

Drew Dixon:

Well, you know, I hope that the innovation that has always defined hip-hop and has always defined Black music, period, can be applied to thinking outside the box about how we want to handle gender, gender violence, and examining our own culpability in emulating the worst of mainstream culture.

I think what’s so problematic is that hip-hop sort of reflects the mainstream society, and it sort of came of age starting in the 70s, but really boomed in the 80s, the greed is good era. And then, fortunately, a lot of the impulses were to copy the sort of materialism and the sexism of the mainstream culture without examining it. And I think that if we can season our food, and we can clap on the two and the four, we can also decide that we don’t have to be the same way the mainstream culture is when it comes to casting couches and rape culture and making excuses for sexual predators.

I don’t care about Harvey Weinstein and this one and that one and the third one. We are already too vulnerable in this society to emulate that, and I’m so tired of my brothers and God, I love my brothers, and I will always love my brothers, and I’m raising a young Black man, but we cannot be in such a hurry to emulate what white men get away with and call that progress because it’s coming at the expense of Black women and girls.

We have to do better. We season our food, and we can do better that they do when it comes to the way we respect our women and our girls.

Michele Goodwin:

Wow. Wow. What a powerful point to end on. I always ask a closing question of my guests, and it is what’s the silver lining? You know, in the sort of darkest of days and times, it can seem like it’s only that, but is there a line of hope that we can think about within these spaces? And so, as we wrap up, Janell, let me quickly start with you, and I’ll close out with you, Drew.

Janell Hobson:

The silver lining, well, to me that is Black culture. We’ve always had hope, no matter what. And I’m always encouraged by the ways in which we’ve been able to hold on, and we’re still here because we’ve had hope because we had our music.

So, I’m always going to be hopeful that there will always be innovations in Black music. I don’t know that we’re necessarily hearing it now. And there are a lot of threats, not just in terms of the perpetuation of misogynoir, but also in terms of AI and what that might do in terms of altering just Black autonomy in general. So, there’s a lot for us to think about, not to mention larger issues like climate crisis and whatnot. I mean we really are at a precipice.

But I’ve also been encouraged because I’m someone who recognizes myself as like hip-hop generation, as you know, I grew up with it, I was born also, same year, 1973, giving my age away, but you know, born the same year as hip-hop, born not far from Cedric Avenue where it was birthed. I am very much Bronx native, you know, went through high school even in Brooklyn.

And I remember when my high school friends, you know, showed up for the “Fight the Power” music video that Spike Lee filmed, so I’m very much part of that culture, and then I grew up with all of it. So, I’m very aware of the kind of changes that we’ve been through and how the younger generation is also having their own iterations of it, and so I’m always going to be hopeful.

But I do, I agree with Drew that we can’t be emulating the powers that be, the hegemony, the white supremacist heteropatriarchy that still girds how we look at so many issues because it was hip-hop that did give me a sense. Before I even entered college, it was Queen Latifah’s “Ladies First” that introduced me to al feminist consciousness before I read bell hooks, so, okay. So, that’s where I’m coming from.

Michele Goodwin:

I hear you. Drew, what do you see as a silver lining?

Drew Dixon:

This conversation right here is the silver lining for me, the fact that we are talking about things that used to be whispered and ignored. Sexual violence is like moss. It grows in the dark kind of counting the fact that what they do is so odious and so humiliating that it will never be discussed, and the light, you know, bright light of truth is the greatest antiseptic of all.

So, let’s just keep talking about it, and I believe that’s just how we make the difference. And I agree with you, Janell. We are related to people who survived in the belly of a boat.

Janell Hobson:

Yes.

Drew Dixon:

And I don’t know how they survived in the belly of that boat, but they did, and so we can, and we are here, so as long as we have a heartbeat and a microphone. We … I have hope.

Janell Hobson:

Yes.

Drew Dixon:

I will always have hope.

Janell Hobson:

Absolutely.

Michele Goodwin:

Janell Hobson, Drew Dixon, I thank you so much for joining me for this episode of On the Issues. Thank you so much.

Drew Dixon:

Thank you for having me.

Janell Hobson:

Well, thank you for having me.

Michele Goodwin:

Thank you.

Guests and listeners, that’s it for today’s episode of On the Issues with Michele Goodwin at Ms. magazine. I want to thank each of you for tuning in for the full story and engaging with us. We hope you’ll join us again for our next episode where you know we’ll be reporting, rebelling, and telling it just like it is.

For more information about what we discussed today, head to msmagazine.com and be sure to subscribe. And if you believe, as we do, that women’s voices matter, that equality for all persons cannot be delayed, and that rebuilding America and being unbought and unbossed and reclaiming our time are important, then be sure to rate, review, and subscribe to On the Issues with Michele Goodwin at Ms. Magazine in Apple Podcast, Spotify, iHeart Radio, Google Podcast, Stitcher, wherever it is that you receive your podcast.

We are ad-free and reader-supported. Help us reach new listeners by bringing this hard-hitting content in which you’ve come to expect and relay upon by subscribing. Let us know what you think about our show, and please support independent feminist media. Look for us at msmagazine.com for new content and special episode updates. And if you want to reach us, please do so. Email us at ontheissues@msmagazine.com. We do read our mail.

This has been your host, Michele Goodwin reporting, rebelling, and telling it just like it is. On the Issues with Michele Goodwin is a Ms. magazine joint production. Michele Goodwin and Kathy Spillar are our executive producers. Our producers for this episode are Roxy Szal, Oliver Haug, and also Allison Whelan. Our social media content producer is Sophia Panigrahi. The creative vision behind our work includes art and design by Brandi Phipps, editing by Will Alvarez and Natalie Holland, and music by Chris J. Lee.

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.