It was Aug. 11, 1973, in The Bronx borough of New York City. In the rec room of an apartment building on Sedgwick Avenue, Clive Campbell, better known as DJ Kool Herc, threw a back-to-school party with his younger sister Cindy. From behind two turntables, Campbell played two copies of the same record in a way that interchangeably looped the instrumental portion emphasizing the drum beat—referred to as the “break”—and elongating it. The dancers, whom he called “break-boys” and “break-girls,” were egged on by Campbell’s announcements and exhortations, skills of the emcee (MC) whose job was to “move the crowd.” The rhythmic vocal accompaniment to the beat laid a path for what would become known as rapping.

This is the moment widely considered to be the birth of hip hop: One DJ in one room surrounded by his community composed of dancers, artists, musicians and poets.

However, hip hop is more than just a genre of music or a style of dance, and it’s more than the work of just one man. DJ Afrika Bambaataa, of the hip-hop awareness group Universal Zulu Nation, is credited with establishing the five pillars of the hip-hop culture: the MC, the DJ, breakdancing, graffiti and knowledge. It’s a way of life—one full of artistic expression and personal agency. Regardless of the exact defining moment of “hip hop,” the culture has been growing and evolving for 50 years, which in perspective of cultures around the world is infantile. The future of hip hop has no boundaries.

Before speculating where hip hop might go though, it’s important to understand where it’s been. Hip hop was born within marginalized communities, pioneered by African Americans, and its development and history is intrinsically linked with racism. By the mid-1990s, hip hop had become one of the best-selling music genres, yet Athens hip-hop artists struggled to perform in downtown venues while the alternative rock music scene was on fire.

In the present, strides are being made to recognize and rectify the struggles and treatment of the African-American community. Among these is highlighting the role of hip hop in Athens, which continues to grow and flourish within the creative community. In honor of hip hop’s 50th anniversary this year, Athens-Clarke County Mayor Kelly Girtz declared May 18 to be Athens Hip Hop Appreciation Day.

“This has always been a creative community, but it has not always been a community that equally recognized the diversity of creativity present in Athens. Noting the strength and quality of a Black-rooted art form like hip hop makes it explicit that Athens is a place that honors all residents for their contributions,” Girtz said in an email to Flagpole about his proclamation.

In recent years, hip hop has become a permanent fixture in the downtown streets of Athens with the addition of Athens Music Walk of Fame plaques dedicated to legendary hip-hop artists Lo Down & Duddy and Ishues. Hip-hop performances and showcases started to gain traction downtown in the early 2000s. Before that, there weren’t many hip-hop shows in the way that we think of them now, but there was a growing pocket of the culture that found places to thrive in the ‘80s and ‘90s.

Poet and spoken-word artist Angela Phinazee, known by the stage name Angela the Arsonist and as the “mother of Athens hip hop,” spent the late ‘80s and early ‘90s dancing at Athens Skate Inn’s “soul night.” At that time, she says there was nothing like that happening downtown, and a lot of people had to venture to Atlanta for performance opportunities. At Athens Skate Inn, a monthly soul night turned into a bi-monthly event, but the primary focus was on DJs and dancing. However, Phinazee notes there were talent shows where people could show off their different art forms.

A few of the scene regulars Phinazee recalls are her DJing and dancing cousin Sean Lindsey, known as DJ Sean Swift; breakdancer Willie Wester; hip-hop artist Cedric Huff, known as Amun-Ra; and dancer Rollin’ Joel. The Krystal’s on Prince Avenue was the designated hangout spot for after the events, where everyone would refuel and continue dancing and having a good time. In spite of the crowd that would form, Phinazee says there was never any fighting or worry about violence, it was always simply “fun.”

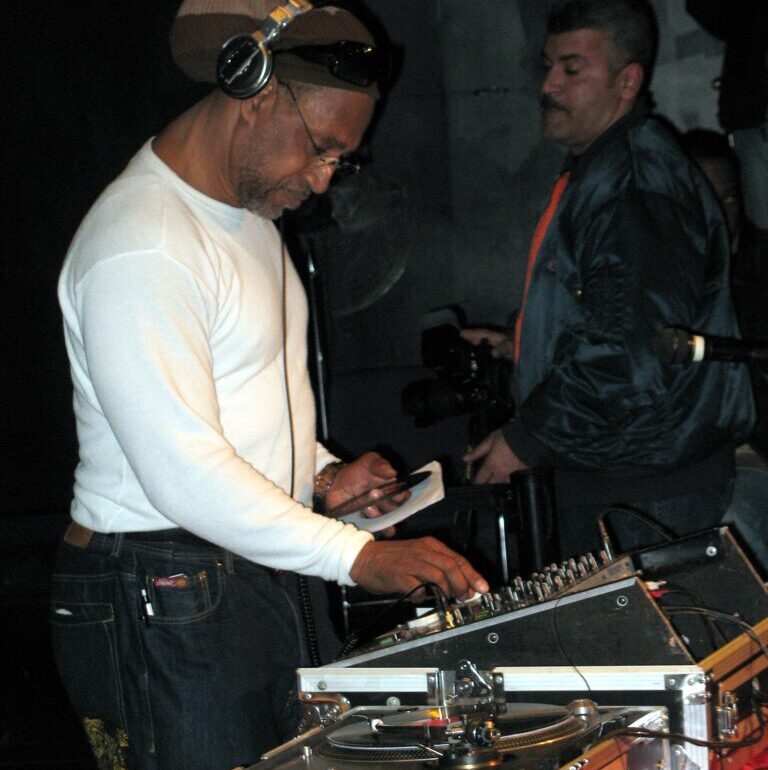

Before Phinazee’s cousin became DJ Sean Swift, Lindsey was also on the scene as a breakdancer in the ‘80s. The skating rink was the go-to spot, but the house party scene was also large, and Lindsey would participate in breaking events outside of the city between Athens and Atlanta. Webster and Bruce Chambers were two of the breaking pioneers, says Lindsey, who taught him the ins-and-outs of the culture and dress code.

“For me, breakdancing was a way to express yourself,” says Lindsey. “You was showcasing your talent. But if we had a little small beef or something like that, we would go to the skating rink and we’d battle it out. It was the outlet for us to where we also had fun doing it.”

An interest in DJing was passed down from his stepfather, and local DJs Foster, Thurman Thrasher and Tariq Kemp playing at school dances inspired him to learn more. But for Lindsey, in the late ‘80s and early ‘90s, “dancing was where it was at.” At that time the YEEK! movement, a style of dance, was growing in Atlanta. Lindsey and his friends would frequent clubs in Atlanta, and they quickly picked up on this new dance, which they brought back to Athens. The crew practiced the routines and got the preppy dress code together, from hair to shoes, then participated in summer events at Bishop Park and talent shows in Oglethorpe County, Monroe and Winder.

As for Phinazee’s own personal craft, she turned to poetry as her focus and began frequenting the Athens open mics downtown by herself. Breaking into the industry, both as a woman and an Athens artist, was a difficult task with a lot of challenges. So Phinazee returned to the root of it all as “poetry and rhythm gave birth to rap, which evolved into hip hop,” she says. Facing similar struggles was Athens’ first female emcee, Shannon Smith, whom Lindsey says would “really go toe to toe” with the male emcee rappers.

In the ‘80s and early ‘90s, Smith poured herself into being a rapper and recorded in closets, basements and event facilities in downtown Athens while performing in surrounding cities like Monroe and Eatonton. As she made her way to Atlanta for more opportunities, she says she was “die hard solo” with a manager who believed in her, but as a woman she felt she had to fight. Some of the same struggles still facing women artists today, like being overly sexualized or expected to exchange favors for fame, were prevalent. But through Smith’s hard work, she opened for artists like Freak Nasty, Raheem the Dream and Kizzy Rock while in Atlanta.

Facing these challenges when women were fighting for respect in hip hop has left Smith critical of modern female rappers who seem preoccupied with keeping up with their male counterparts instead of carving their own lane. “What’s popular is not the people telling their stories. That’s not hip hop,” says Smith, when reflecting on the golden age of hip hop that valued telling stories from life, your hood, police brutality and other politics. Even so, Smith is still a “cheerleader” for the “authentic” and “real.”

“If people would just understand how important that is when we open the door, then other people can get their foot in. Instead of just hating on the one person that has arrived, support them,” says Smith.

In the late ‘90s, Athens hip hop was knocking on doors and building momentum that began to finally breach the downtown music scene. Multi-talented dancer, rapper, poet and comedian Showyn Walton, affectionately known as Buddah, reminisces on performing with hip hop-based bands that were welcomed onto mixed-genre bills at downtown venues. Walton specifically mentions performing alongside punk rock and jam-based bands, which are two genres that still remain seemingly more open to collaborating with hip hop in Athens.

“The first band we put together wasn’t a very good band—our bassist couldn’t even play bass,” laughs Walton, but having a rapper with a live band afforded more opportunities in the Athens scene. While creatives like Walton were busy making opportunities and finding ways to bring the growing national success of hip hop to Athens, they were also encouraging and inspiring the second-wave generation of hip-hop enthusiasts.

“It’s a big deal when you see someone that looks like you doing something you love doing,” says Walton.

As a teenager in the ‘90s, writer, emcee and culture aficionado Jabrell Winfrey, known as Billy D. Brell and the Talented Mr. Winfrey, was at the center of hip-hop culture—despite his mother’s disapproval. During his senior year in 1997, K. P. & Envyi performed at the Clarke Central gymnasium with him and a few other students opening for the group. He recalls during the ‘80s and ‘90s that a lot of people in the South didn’t think it was possible to be an emcee, so they took to the other elements of hip hop. But in Athens, Lo Down and Duddy were the first rappers he points to as showing people it was possible to be successful in that way. Personally inspiring to Winfrey was Ken Bloodsaw, who took him under his wing and guided him into the studio.

It wasn’t until 2001–2002 that Winfrey saw local hip-hop artists putting on their own shows, especially downtown, which was prompted by William Montu Miller and the campus group he started, Dreaded Mindz. Tasty World and Miller’s “Tasty Tuesday” hip-hop showcases are still often talked about in regards to hip hop breaking into downtown, but before that, Miller hosted events in 2000 at his apartment, dubbed The Lounge. There were poetry Thursdays and hip-hop Fridays—from which flyers are currently on view in the “House Party” exhibit at UGA’s Special Collections Library.

During that time period, Winfrey names three other individuals that were responsible for pushing the hip-hop scene forward musically. Ishues Cuthbertson brought “the real emcee essence to a Southern scene.” Tony Bradford was respected by both the downtown and street scenes, says Winfrey, and was one of the first people to bring big artists to Athens, like Nicki Minaj before she blew up. Winfrey highlights Eugene Willis, who performs as BlackNerdNinja, as someone he watched while still in high school working jobs to pay for studio time and record projects when that wasn’t a norm, and he pushed the boundaries of live performance in the city.

By no means is this an exhaustive list of movers and shakers in the early Athens hip-hop scene, nor does it name every place within Athens that hip hop was happening. It’s merely a reflection on how the scene has grown, and some of the people responsible for it. Likewise, hip hop as a culture and as a musical genre has seen a lot of growth, and change is not always viewed positively by all. But it’s still a sign of progression. Winfrey leaves us with this:

“I feel like that’s the best way to love the culture: It’s just like a child. You love a child to death, but it gets to a certain point you can’t control what that child does. How can you still expect it to be the same at 50 years old?”

Like what you just read? Support Flagpole by making a donation today. Every dollar you give helps fund our ongoing mission to provide Athens with quality, independent journalism.

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.